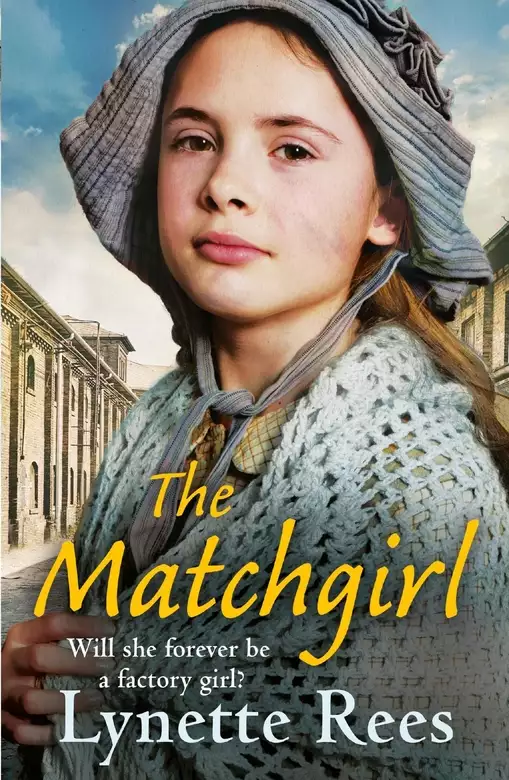

The Matchgirl

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A heartwarming saga, from the ebook bestselling author of THE WORKHOUSE WAIF Sixteen-year-old Lottie Perkins has an important decision to make... Conditions at the match factory she works at are dire. The girls get treated badly by the management and there is a severe risk to their health. But then a young journalist, Annie Besant, begins asking questions. Will Lottie and the other girls welcome her help, even when it could cost them their jobs - and their livelihoods...? Please note: this edition contains editorial revisions

Release date: July 26, 2018

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 234

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Matchgirl

Lynette Rees

The sounds of shouts and clatters in the street caught the attention of sixteen-year-old Lottie Perkins. She raced over to the living-room window to raise the old lace curtain to take a peek at what was going on outside. She’d risen early to begin a day’s work at the Bryant and May Match Factory at Bow. And now she stood watching the Higgins family from across the road outside their house in a state of distress. Mr Higgins was trying to round up all the kids as his wife attempted to settle the baby. All their worldly goods were piled on top of an old wooden hand cart. Why were they leaving? It was a mystery to her. Had they found somewhere better to live instead of this grimy old place? But Mrs Higgins’ face told a different story; etched on it was the look of despair as she carried the baby, patting his back to quieten his pitiful cries. A couple of neighbours had arrived to see them off, with lots of hugs and kisses. Oh, how they were going to be missed around here.

She sighed as she dropped the curtain. She had thought it would be a day like any other today; the days were so repetitive at the factory.

She could’ve been destined for better things in life, Lottie was well aware. The conditions they endured in the factory were sometimes insufferable and she often thought about what her life would be like if her father hadn’t passed away and her mother not fallen out with Lottie’s rich aunt, Dorothea. Lottie ought to have soft hands like a lady but instead hers were chapped and sore. They never looked clean somehow and no matter how hard she scrubbed them after working at that place, they still looked slightly soiled. Lottie’s eyes scanned her humble home, the threadbare carpets and peeling wallpaper making it appear somewhat shabby. Nowadays, they had to make do and mend: with four younger siblings, there were six mouths to feed in the household and money was tight.

Lottie let out a little sigh as she returned to the scullery to sip her hot sweet cup of tea. She became aware of a presence beside her.

‘Enough there for another cuppa, is there, love?’ her mother asked, gazing at Lottie.

Lottie studied her mother’s weary face. She’d worn the same black bombazine dress for months to mourn her dear Albert’s death. In truth, Lottie had been extremely worried about her need to remain indoors and how she’d retreated inside her shell when she’d been such a feisty woman when Pa was alive. But today, there were signs she was about to emerge from that very same shell: she wore a grey Linley wool dress just like she had before Pa’s death. Was her long period of mourning really over?

Lottie smiled and let out a little sigh of relief. ‘Oh Ma, of course there is. It’s unusual to see you up and about.’

Ma took in a long breath and let it out again. ‘I’ve decided I need to get a job. I’m coming with you into the factory this morning to ask,’ she stated firmly. ‘Will your boss, Mr Steed, be in today, do you think?’

Lottie nodded. ‘He should be. He’s the man you need to speak to, Ma.’

Lottie studied her mother’s face. Her sunken eyes and hollow cheeks were testament to her recent grief. Her skin looked pale and sallow. Lottie had recently had a long chat over the garden wall to their next-door neighbour about her concerns for Ma, remembering Doris’s words about giving her mother something to live for. She decided not to put her mother off. It was the first time she’d seen her show any interest in anything at all.

Lottie chewed on her bottom lip. ‘Are you sure? You know what it’s like at the factory, Ma. They are dreadful taskmasters. They don’t give us very good breaks and the pay is poor. We work long hours and get treated no better than pack horses.’

Ma nodded and then stuck out her chin, defiantly. ‘I realise all of that,’ she said quietly, ‘but if I don’t do something I fear I will live like this for the rest of my life and I can’t fall apart. You all need me, particularly the young ’uns.’

For a moment, Lottie wondered what had prompted her mother to change her mind but before her mother could answer, she cleared her throat and said, ‘Doris from next door called to see me when you were at work yesterday. Gave me a good talking to, she did.’

Lottie smiled through blurry eyes. At least her mother was trying to get back in the land of the living rather than burying herself in a grave alongside Pa.

‘You make the tea and I’ll toast the bread,’ Lottie said, lifting the toasting fork from a nail that hung on the wall beside the stove.

Her mother nodded and wiped away a tear with the back of her hand. It wasn’t going to be easy for any of them. In fact, the past year had been extremely difficult.

‘What about the kids when you’re at work though, Ma?’

‘I’ve thought of that. They’ll be at school most of the day and if I ask for opposite shifts to you, we can work something out.’ She rolled up her sleeves as if that was somehow a gesture of confidence in what she had planned for her family. ‘Also, Doris has said she can pop back and forth to check on them when they come home from school. Besides, the girls are old enough now: Bessie is twelve and Daisy eleven, both old enough to take care of themselves and their little brothers.’

Lottie’s young brothers, Freddy and Davy, were twins and the youngest of the family at just five years old. Identical in almost every way, except that Davy, the younger of the two, had slightly more freckles and that’s how most people told them apart. But Lottie could tell the difference between the two in a blackout cellar. To her there were differences that others might not notice if they didn’t know them as well. Davy spoke slower than Freddy, and Freddy often answered for his younger twin, which made people think Freddy was the more forward for his age, where in fact the opposite was true. It was Davy who was the most intelligent and who spent his time reading, while Freddy preferred to be outside in the street playing pitch and toss or marbles.

How she loved her brothers and sisters and wished she could do more for them. It was heartbreaking they’d all had to lose their father at such a tender age.

She supposed her mother was right. It wasn’t unusual to see latch-key kids around the East End of London. It was quite normal for children to fend for themselves while their parents worked or indeed to even work themselves. Some as young as six years old were expected to work long hours for a pittance; due to their small stature and being light on their feet they could do things adults couldn’t do, like going up soot-filled chimneys. Some of the work given wasn’t suited to their ages and they suffered as a result. Even worse were those poor children who got thrown into the workhouse as either their parents died young, couldn’t cope with them, or entire families were left homeless due to poverty. Lottie didn’t want to see their family being split up – what would happen if money became short? Up until now, they’d coped, but money was running out. With six mouths to feed and no longer a male head of the house to provide them with a regular wage, Ma getting a job at the factory would really help keep their heads above water, at least for the time being.

Remembering the commotion opposite, Lottie turned to Ma. ‘Why are the Higgins family leaving their house opposite, Ma?’ She took a bite from the crusty toast which had very little dripping spread on it. Economy was needed right now. If they were all to survive, they could no longer afford to be lavish with anything.

Ma frowned. ‘Is it today they’re off?’ She stood and walked over to the window, lifting the curtain to watch them say their goodbyes outside. Then shaking her head she turned back to her daughter. ‘Doris told me they couldn’t afford the rent. They’ve been turfed out on to the streets by the rent man. I don’t much fancy their chances of keeping out of the workhouse now . . .’

Lottie guessed the family had very little option now than to enter that place. She chewed her bottom lip. ‘Ma,’ she began.

‘What, Lottie?’ Her mother’s eyes looked full of concern.

‘Could that happen to us? Could we get thrown out of our home, too?’

Ma slowly nodded her head. ‘It could. It was when Doris told me about the Higgins family that it brought me to my senses. I’ve been in a daze since your father died. I need to pull meself up by me boot straps. Poor Arnold Higgins got himself in money difficulties when they wouldn’t give him no more work at the docks. The poor chap had to line up with all the other men when they were chosen for a day’s work and he failed to pass muster. They want strong fit men there. There’s no sentiment in business, you’ll learn that someday, my gal!’

Lottie thought she’d learned that already from the way the bosses were acting at the factory, putting profit before the workers’ welfare, but she didn’t want to tell her mother that today. She didn’t want to put her off. She hadn’t seen her mother so fired up in a long while.

*

Following breakfast, Lottie and Ma donned their jackets and hats, and made their way towards the Bryant and May Match Factory in Fairfield Road, Bow, which was only a couple of streets from their home. In the distance, they could clearly see its tall stack standing loud and proud as it beckoned its workers to draw nearer. Three years previously, Bryant and May had merged with the firm Bell and Black, which had factories in Stratford, Manchester, York and Glasgow – that’s how big the firm had become, yet still they treated their mainly female workforce badly, despite an increase in finances.

Lottie’s mother stopped to rap on the door knocker next door to theirs, and then Mrs Munroe appeared bleary eyed on the doorstep.

‘’S ’oright. I’m up and about, Freda,’ she reassured her. ‘I’ll let meself in through the back way and get breakfast ready for the kids. You feeling ’oright, today?’

‘Yes, never better, Doris. Thanks for all of this. I’ll make it up to you. Maybe I can take in washing for you or something?’

‘Don’t worry, I’ll think of something,’ Doris replied gruffly, rubbing her coal-blackened face. She’d obviously been up early lighting the fire. She wasn’t one for glamour, Doris Munroe. Her children were all grown up, apart from one son who had never married and stayed at home with her and his father. His name was Ted. Lottie was convinced that Doris was lining her up to marry him. She didn’t much care for Ted. He was a few years older and she found him tedious to talk to. They had nothing whatsoever in common and she avoided him if she could. But she was unlucky today – as Ma and Doris chatted on the doorstep, she felt someone come up behind her and squeeze her waist with two strong hands. She turned and felt her cheeks flush red with embarrassment. ‘I wish you wouldn’t do that, Ted!’ she snapped, her mother and his oblivious to their altercation as they spoke about the Higgins family’s departure.

‘Couldn’t resist!’ He winked. It was then she noticed the newspaper tucked under his arm.

‘Just finished a night shift at the docks, have you?’

‘Aye. Trouble is the bosses are making most of the workers work day to day now, not like when your father was alive. Things were better then. Our jobs were safer. There’s a lot of unrest.’ He unfolded the newspaper to show her a headline. ‘I reckon there’s trouble afoot there.’ He whistled through his teeth, a habit she found most annoying.

Lottie nodded and turning to her mother said, ‘Come on, Ma, or we’ll be late.’

‘I’m coming!’ She said her goodbyes to Mrs Munroe and Ted, then followed after Lottie, falling in step with her.

As they made their way along the long grimy street with its identical doors and windows and reddish-brown brick walls, Lottie turned to her mother, who marched with extreme purpose. ‘Ma, I hope Mrs Munroe isn’t helping us out because she plans on demanding a favour in return.’

Her mother stopped in her tracks. ‘What the devil do you mean?’

Lottie stopped too. ‘Well, I . . . I . . . just get the feeling she would like to see me married to her Ted.’

Her mother chuckled. ‘No, don’t be so daft, gal. Ted’s not the marrying kind. He’s bound to his mother’s apron strings. No girl will ever be good enough for her son, in Doris’s eyes, even you, Lottie Perkins. Come on, we better get a shift on or you’ll be late.’

Breathing a sigh of relief, Lottie followed her mother along the shady street. The gas lighter was in the process of extinguishing the lamps as they spilled out pools of light, casting a golden glow on to the pavements below. Dawn would break soon. It was like going to work at night time. Lottie saw little daylight, especially in winter – it could be so depressing. The smell of horse manure in the gutter mingling in with the clouds of sulphurous smoke belching from the match factory made Lottie’s stomach turn. They were smells she never quite got used to and were stronger in summer than winter.

In front of them were groups of other girls and women marching towards the factory in wooden clogs or hobnail boots. Most were chattering away. They seemed to march to a rhythm that was almost like a drum beat in quality. Lottie had often noticed that, but no one else ever mentioned it. Maybe she daydreamed far too often. Her father used to say she had a romantic soul. Along the way, groups of girls acknowledged others. Every girl with a tale of her own to tell – some happier than others.

When they approached the factory gates, her mother went off to seek out one of the foremen to enquire about speaking to Mr Steed about a job. Lottie worried if her mother had the stamina to stand up and work for ten hours a day with very few breaks in between. It was not for the faint hearted and Ma had been a little delicate of late.

As Lottie entered the factory floor, the din of machinery and chatter was deafening. Her best friend, Cassie Bowen, was in the process of dipping matches into a chalk-white powdery chemical called phosphorus.

‘How are you doing, Cass?’ Lottie called out to her.

The girl grimaced. She hadn’t seemed her usual self of late and Lottie was becoming quite concerned. ‘Fed up to the back teeth of it all, tell you the truth, Lottie. This stuff is starting to sting me face and I keep getting headaches an’ all!’ she shouted over the din, then brushed back a lock of hair that had fallen from her mob cap onto her face and began to cough. ‘It’s even affecting me lungs now as well.’ She wiped the back of her powdered hand under her nose. ‘My nose is always dripping too.’

Lottie laid a hand on the girl’s shoulder. ‘I think you need to be careful with that powder on your hands, Cassie. You need to wash them when you can.’

‘I know but the foreman plays hell if I leave me work station. Sometimes I even eat me food here and still have powder on them.’

Lottie frowned. ‘This isn’t right at all. I’ve seen how you’ve gone downhill since working here. We need to ask Mr Steed if he can move you elsewhere, maybe the packing department. He might move you if you explain things to him.’

The girl working beside Cassie laughed. ‘Stop acting like a lady, Lottie. Yes, Lady Lottie I’m going to call you from now on with your big ideas!’

‘I was only trying to help.’ Lottie was fed up that some of the girls poked fun at how she spoke. Aunt Dorothea had taught her to speak properly and given her piano lessons too and said how her father had been from good stock, but the girls here wouldn’t understand any of that so she never told them about her family’s past. ‘I still think it wouldn’t hurt to ask.’

Cassie glared at the girl. ‘Look Polly, Lottie was only making a suggestion, weren’t you?’

‘I was and all,’ Lottie said feeling most affronted. ‘I just think if you don’t ask you don’t get!’

Polly shook her head. ‘Ha, you’re jokin’ aint you, gal! I been asking to be moved meself for months, but it’s fallin’ on deaf ears. Mr Steed keeps refusing. He ain’t interested in how we feel as long as he gets the work out o’ us.’

Lottie sighed. They shouldn’t have to put up with this kind of thing. But what could they do about it? ‘I’ll speak to you later, Cass,’ she said. ‘I can see the foreman watching me. I need to get to my work.’ She couldn’t risk a ticking off or a cuff around the earhole today of all days as it could scupper her mother’s chances of landing herself a job.

Cass nodded and smiled. ‘All right, Lottie. It’s only you that keeps me going in here. Will I see you later?’

‘You can count on it. We can walk home together and think what can be done about this.’

Flossie, Lottie’s workmate, cornered her before she even had time to remove her shawl and hang it on a peg. ‘’Ere, have you heard the latest news?’ Her eyes shone excitedly.

Lottie shook her head. ‘Sal’s had the baby?’ Sal was a young unmarried woman who’d got pregnant out of the blue. Rumour had it that the father was one of the foremen, but Floss and Lottie had no idea which one and Sal hadn’t told them either. Floss frowned. ‘No, not that. There’s a woman who’s been asking women questions about the working conditions here.’

Lottie blinked several times. ‘That’s the first I’ve heard of anything like that. Who has she spoken to?’

Flossie drew a quick breath as if she wanted her words to tumble out as quickly as possible before she was overheard by anyone. ‘I spoke to her last night. She clocked me on me way ’ome and she asked questions of a few others outside the factory gates.’

Lottie quickly scanned the factory floor to ensure they weren’t being watched. If they were caught gossiping it could mean a back hander from one of the foremen, and it would have even worse consequences if they realised the subject matter. ‘Do you think that was wise? You could lose your job, Floss! It’s not worth it.’

Floss lowered her voice to barely a whisper. ‘Look, Lottie, yer know as well as I do ’ow bad things have got here. ’Alf the time we’re not even allowed to go to the lavvy for a pee. Poor Ginny Malone had her courses last week and needed to go to the lav and wasn’t allowed out, and as a result, bled all over the factory floor. It was like a slaughterhouse in here!’

Lottie sighed. She guessed Floss was exaggerating the situation, though she felt for the poor girl. ‘That’s dreadful,’ Lottie sympathised.

Floss nodded and carried on. ‘Yeah, it is. It were the boss’s fault. She was made to clean up all that blood and they wouldn’t even allow her to rest up afterwards neither, even though she had a bad belly.’

Lottie nodded. ‘I know it is wrong. I’m not saying it’s not, but what I mean is we could lose the jobs we already have if we speak out against what goes on here. There’s no woman going to change anything for the likes of us. I reckon we ought to talk to Mr Steed ourselves first.’

Floss’s eyes glittered. ‘This woman is different though, Lottie. She’s a real lady. She talks proper, dresses posh ’an all. Educated, like. She knows what she’s on about. She told me she’s going to help us all by getting the word out. Ain’t that grand? She wants to tell everyone how badly we get treated ’ere!’

Lottie gulped. ‘I hope she doesn’t go naming names and dropping any of us in it. My poor mother can’t manage as it is – that’s why she’s come to ask for a job here today. If I should lose my job it could be the workhouse for us all. I couldn’t bear to be split up from the kids. I really don’t want to get into trouble over some posh woman and what she says.’

‘I know, and we do have to be careful, but there’s other stuff that’s not right ‘ere. Poor Martha keeps getting headaches and her jaw is swollen. Me Ma thinks she’s got that phossy jaw thing from that white stuff we’re using to make the matches.’

Lottie knew her friend was right. One woman had been sent home with something similar and never returned again. There’d been a rumour that she needed an operation to have part of her jaw removed but she didn’t have the money to pay for it. Didn’t Cassie just say she’d been suffering from headaches too?

One thing was certain, never mind the poor pay and working conditions at Bryant and May, there was a danger to the health of those working there. The British government, so far, hadn’t banned the dangerous substance, unlike America and Sweden.

The common work-day was ten hours long and for most of that time, Lottie and Floss were on their feet cutting in half the long strips of wood, both ends of which had been dipped into a compound of chemicals to create the match-heads. The cut matches were then packed into boxes by a team of young women. It was a dangerous job and Lottie was aware of the need to keep her concentration.

Flossie had told Lottie that Bryant and May had actually lowered wages earned over the years, so they weren’t even earning as well as workers were twelve years ago. Though she didn’t know that for certain, she guessed it was rumour mongering amongst the women who had older relatives working there.

There was also a tale Lottie had heard of how a statue of William Gladstone had been erected at Bow Road outside the church, in honour of a planned visit from the prime minister. Surely it couldn’t be true what she’d been told that the women had to pay towards the statue themselves from their very meagre wages?

Floss had told her that her mother had said each girl had a shilling deducted from her wages. When the women discovered this, they were outraged. Why should they have to spend their hard-earned money on something like that without even being asked? Many of them went to the unveiling of the statue armed with stones and bricks to fire at it and then they cut their arms allowing their blood to spill on the marble plinth. It all reminded Lottie of a sacrificial altar of sorts. Maybe that’s what the women had been trying to convey – how much they’d sacrificed working at the factory, even their life blood.

The smell of the white phosphorus from the match-dipping machines lingered in the air, causing the women to cough and wheeze. Lottie noticed that some of them had a strange yellow tinge on their skin. They really looked unhealthy. She was glad that she work. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...