- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

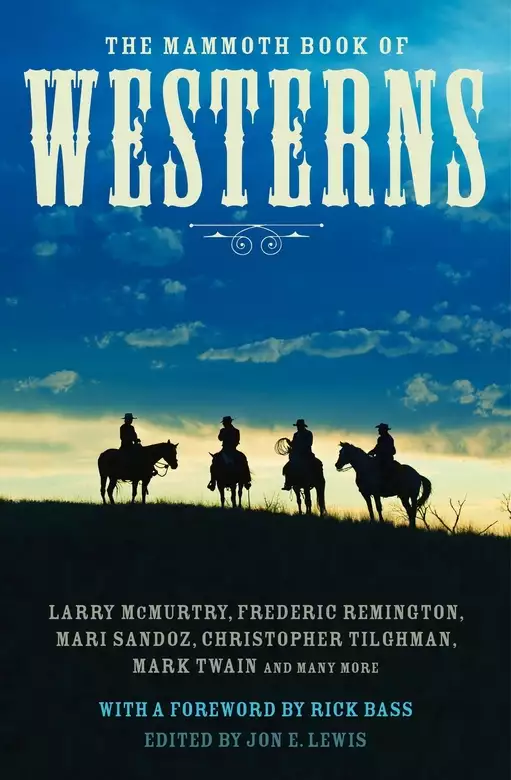

The Western, though a singularly American art form, is one of the great genres of world literature with a truly global readership. It is also durable despite being often unfairly maligned. Ever since James Fenimore Cooper transformed frontier yarns into a distinct literary form, the Western has followed two paths: one populist - what Time magazine famously billed 'the American Morality Play' - capable of taking many points of view, from red to redneck, but always populist, with a sentimental attachment to the misfit; the other literary - eschewing heroism, debunking with unsettling candour many of the myths of the West. It can sometimes be difficult to draw a sure line between the two forms, but both are represented in this outstanding collection which includes stories by Rick Bass, Walter Van Tilburg Clark, Larry McMurtry, Mari Sandoz, Christopher Tilghman, and Mark Twain, among many others.

Release date: July 4, 2013

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Westerns

Jon E. Lewis

Introduction and this arrangement © 1991 & 2012 by J. Lewis-Stempel

“The Ranger” by Zane Grey. Copyright © 1929 Zane Grey. Copyright renewed 1957 by Lina Elise Grey. Originally published in Ladies Home Journal. Reprinted by permission of Zane Grey, Inc.

“Early Americana” by Conrad Richter. Copyright © 1934 by Conrad Richter. Reprinted from The Rawhide Knot and Other Stories by Conrad Richter. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

“The Wind and Snow of Winter” by Walter Van Tilburg Clark. Copyright © Walter Van Tilburg Clark, 1994.

“When You Carry the Star” by Ernest Haycox. Copyright © 1939 by Ernest Haycox. Copyright renewed 1966 by Jill Marie Haycox. Reprinted from Murder on the Frontier by permission of Ernest Haycox, Jnr.

“The Young Warrior” by Oliver La Farge. Copyright © 1938

Oliver La Farge. Copyright renewed 1966 by Consuelo Baca de La Farge. First published in Esquire. Reprinted by permission of the Marie Rodell-Frances Collin Literary Agency.

“The Big Sky” excerpt by A. B. Guthrie. Reproduced by permission of Hougton Mifflin. Copyright © A. B. Guthrie, 1947.

“Command” by James Warner Bellah. Copyright © 1946 James Warner Bellah. Reprinted by permission of Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc, 845 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022. First published in the Saturday Evening Post, 1946.

“The Colt” by Wallace Stegner. Reprinted from Southwest Review, 1943 by permission of the estate of Wallace Stegner. Copyright © Wallace Stegner, 1943.

“A Man called Horse” by Dorothy M. Johnson. Copyright © 1949 Dorothy M. Johnson. Copyright renewed 1977 by Dorothy M. Johnson. Reprinted by permission of McIntosh and Otis, Inc. First published in Collier’s, 1950.

“Great Medicine” by Steve Frazee. Copyright © 1953 by Flying Eagle Publications, Inc. First published in Gunsmoke, 1953. Reprinted by permission of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc, 845 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022.

“Emmet Dutrow” by Jack Schaefer. Copyright © 1951, renewed 1979 by Jack Schaefer. Reprinted by permission of Don Congdon Associates, Inc. First published in Collier’s.

“River Polak” by Mari Sandoz. Reprinted from Hostiles and Friendlies, 1959, by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright © Mari Sandoz, 1959.

“Blood on the Sun” by Thomas Thompson. Copyright © 1954 by Thomas Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Brandt & Brandt Literary Agency.

“Beecher Island” by Wayne D. Overholser. Copyright © 1970 by Wayne D. Overholser. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Desert Command” by Elmer Kelton. Reprinted from The Wolf and the Buffalo by Elmer Kelton. Copyright © 1980 Elmer Kelton. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Bandit” by Loren D. Estleman. Copyright © 1986 Loren D. Estleman. Reprinted by permission of the author and the Ray Peekner Literary Agency.

“There Will Be Peace in Korea” by Larry McMurtry. Reprinted from Texas Quarterly, Winter 1964. Copyright © Larry McMurtry, 1964.

“C. B. & Q.” by Edward dorn. Reprinted from The Moderns, edited by Leroi Jones, 1963. Copyight © the estate of Edward Dorn, 1962.

“The Man to Send Rain Clouds” by Leslie Marmon Silko. Reprinted from New Mexico Quarterly, 1969. Copyright © Leslie Marmon Silko, 1969.

“The Waterfowl Tree” by William Kittredge. reprinted by permission of the author from Northwest Review, Vol. 8, No. 2 1966–7. Copyright © William Kittredge, 1966.

“Days of Heaven” by Rick Bass. Reprinted from Ploughshares, Vol 17, Fall 1991. Copyright © Rick Bass, 1991.

“Hole in the Day” by Christopher Tilghman. Repritned from In a Father’s Place, 1990 by permission of the author and Markson Toma. Copyright © Christopher Tilghman, 1990.

Just as in a story there are nodes of extreme meaning or imagery, where every description, every line of dialogue, every everything, has enhanced meaning – a kind of luminosity of significance – so too are there in a country nodes, blossomings of terrific output and productivity. In the United States, places like Oxford and Jackson, Mississippi; Key West, Florida; Stanford and the Bay Area in California; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York, Iowa; Seattle, Washington; my own home in Missoula, Montana, have produced incredible cultures of literature.

Sometimes these nodes seem to have been activated by the arrival or development of a single writer, other times by a community, and by the slow accruing culture of place. (And even in those instances where a literary community or legacy appears to have been catalyzed by the arrival of some lone individual, one cannot ignore the possibility that there existed already some nascent quality – landscape, weather, culture, community – that so attracted that individual in the first place.

It’s said often that there are really only two stories in the world: a man or a woman goes on a journey, or a stranger rides into town. Certainly, the open spaces of the American West exist as a beckon and a beacon.

This has always been and remains one of the great values of the American West. Its chief characteristic – more so than even frequent and widespread aridity – is its spaciousness. This great distance between things engenders a kind of exhilaration, as well as a kind of loneliness, and is one of the great generators of writing and storytelling in the West.

There are of course different kinds of loneliness, and different kinds of exhilaration. I suspect the dramatic amplitudes of these emotions in the West are extraordinarily conducive to not just the generalities for creating art, but, more specifically, the writing of stories, stories being perhaps the most portable of art forms.

There is no typical story of the West, or certainly should not be. There can be and are similarities of yearning – of the human heart responding in a certain fashion, to the physical spaciousness, and the communal hardships – but within the milieu of that yearning, the reservoir of any story contains infinite possibilities. The spirit of a Western story, then, will have a certain quality to it, but one should not be surprised by the wild variation – the lush diversity – that will exist in the actions and choices of characters placed within such a dramatic structure, dramatic topography, dramatic space, of the West.

More so than in many other places in the world, I think, almost anything is possible in a Western story.

It’s a sideways anecdote, but I’m reminded of a piece of natural history. The elk that are such an iconic symbol of the West – Cervus elaphus – were once a plains creature, grazing the tallgrass prairies of the Midwest, and indeed, inhabiting even parts of the Eastern seaboard. Destruction of habitat, however, and overhunting, conspired, as it did with the buffalo, to force them up into the mountains, and deep into the forests, often choosing hiding cover over their earlier (and still extant) desires for the rich grasses that grew under the bright sun of the unshaded plains.

And having evolved out on those plains, the elks’ voices became shaped over time into the high flute-like squeal – that anthem to wilderness – that so thrills those who hear and hunt them. The faster-travelling sound waves of that high pitch is the perfect frequency for transmitting sound across a landscape unbroken by hills, mountains, boulders, forests. With no obstacles to deflect the sound waves or cause them to ricochet and be lost, a high bugling fits the landscape.

In a forested landscape, however, a deeper voice would be best – like the subsonic slow sound waves rumbled by forest elephants, the slower sound waves rolling over fallen logs and bending their way around trees, rather than bouncing off the trees and being lost.

Some day, the voices of the elk will probably become deeper, adapting to life in the forest. Ten thousand years? Twenty thousand? For now, however, there is a lag, an echo, in the voice of the then and the voice of the now. What has not changed, however – and will not, for as long as wild country remains – is the quality of wildness in the elk’s voice. It’s hoped that readers will find and enjoy in this collection a similar quality in these stories – sometimes brooding and lonely, other times celebratory and fantastic – but always Western, and of-their-place.

Rick Bass

The Western, it can safely be said, is one of the truly great genres of world literature. Ever since James Fenimore Cooper published The Pioneers in 1823 stories set in the American West have enthralled generations and millions of readers. Even in the 1980s when the Western was supposedly heading towards the sunset (not for the first time in the Western’s life the reports of its death were exaggerated) Louis L’Amour sold more books than almost anybody else on earth. And was read from Abilene to Zanzibar.

While the Western might have a global readership, it is a singularly American art form. No other country has a Western. But then, no other country had a West: that vast spectacular landscape – and even bigger sky – that lies between the Mississippi river and the Pacific Ocean. And no other country has such an epic history of pioneering settlement.

There were other frontiers in other times (South America, Africa) but it was the luck of the West to be rolled back at almost the precise moment that publishing entered the steam age. Mass books could be printed for a mass market. Mass urbanisation played its part too; it was almost as if the nineteenth century huddled city poor yearned for stories about a place of beauty and unpopulated individualism, the diametric opposite of where they were right then.

Mythology, epic history, a willing mass readership – unsurprisingly, writers flocked to the Western like butterflies to a prairie rose. Alas, some of the butterflies turned out to be common or garden moths. The Western might be one of the most durable literary forms; it is also one of the most despised, being commonly considered suitable only for pre-pubescent boys and men who read with their finger under the words, where good characters wear white Stetsons and evil ones pockmarked scowls, and where the only good “injun” is one whose moccasins are pointing skywards.

Of course such fiction exists. But it is not the best of the West, and never has been.

Although stories set in the Wild West existed before the acknowledged father of the Western, Fenimore Cooper, dipped his quill into the ink pot, it was Cooper who turned these frontier yarns into a distinct fictional form with definite shape, characters and themes. In the Leatherstocking Tales, of which the most famous is The Last of the Mohicans from 1826, Fenimore Cooper created the figure of Natty Bumppo, frontiersman and hero. Cooper also gave the Western its lasting focus: the tension between the Wild West and the encroaching Civilised East – a tension played out down the literary years in the conflicts of outlaws v. deputies, cowboys v. homesteaders.

After Fenimore Cooper the Western took two paths: one popular, one self-consciously literary. In its popular form, beginning with the “dime novels” published by New York company Beadle & Adams from 1860 onwards, the main elements of Cooper’s Western fiction became highly formalised, with standard issue characters and plot situations (invariably resolved by violence), and the vaunting of individual heroism. The popular or “formulary” Western became as rigid in its rules as a Noh play. Few readers cared. On the contrary, the more complex civilisation and strait-jacketing factory routines they experienced in their own lives, the more they read an escapist simplified version of the West, where a man or woman could revel in wilderness freedom and any problem be solved by quick resolute action. Time magazine once famously called the Western the “American Morality Play”, and suggested that it is, above all, a form of fictional reassurance. The good guys will win, history is on our side.

There is, undoubtedly, truth in Time’s observation. But the moralism of the Western can be overplayed, so too the notion that it always stands for the same political point of view – usually interpreted as right-wing. The Western, actually, can be made to fit almost any political philosophy from red (Jack London) to redneck (J.T. Edson). If the Western has a natural political centre of gravity it is anti-big capitalist (typified by the banker and the rail magnate). Populism, in a word. A sentimental attachment to the misfit is another hallmark of the genre.

For nearly a century, the heroic West dominated the reading habits of America and Europe. Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902), Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage (1912), “pulp” magazines like Street & Smith’s Western Story (from 1919 onwards) sold by the million, and it took the paper shortages of World War II to seriously dent the circulation figures of cheapend Western fiction. But the pulps came back in the late 1940s for what was the Golden Age of the popular western.

The War changed the Western for good. If the good guy still tended to win, he was less of a clean cut-hero. Moral, social and psychological issues were wrought with greater complexity. A fuller, deeper use of Western history became commonplace. (The evidence was in the new pulps’ titles, for example True West). Nowhere was the new maturity of the formulary Western more evident than in its treatment of the American Indian. Until the 1950s, the Native American in pop Westerns was either a noble savage or a savage savage, but a savage nonetheless. The problem had been exacerbated by the decision of the Curtis magazine group that the Indian point of view must not be shown in its journals after the audience outrage that greeted Zane Grey’s attempt to depict a love affair between a white woman and an Amerindian man in a story for Ladies’ Home Journal in 1922. From the 1950s, it became virtually de rigeur in the Western to treat the Native American sympathetically, with the milestone being Dorothy M. Johnson’s “A Man Called Horse”.

The Golden Age lasted a fleeting ten years or so. By the 1960s television had become the main form of cheap entertainment for ordinary people. Also, the sheer amount of formulary Western stories and novels – not to mention films and TV series – in the 1950s had produced a sense of overkill. The pulps had come to the end of the trail. It is easy to sneer at a form of creative writing that paid a cent per word and where editors issued “How and What” rule books; it is also misplaced. The legacy of the pulps was enormous and is still around us. Writers as diverse as Sinclair Lewis and Elmore Leonard served their apprenticeships in Western pulps, while the special skills of compression and economy demanded by the coarse-paper magazines have worked their way into the brilliance of the contemporary American short story.

Ultimately, though, it wasn’t TV that drove the popular Western towards the sunset. The popular Western no longer fitted the times. By the 1970s a certain urban cynicism ruled the population. The formulary Western can be many things. Except cynical.

Meanwhile, what of the literary Western? Its biography could scarcely be more different from its popular blood brother.

Despite the shared paternity in Fenimore Cooper, the literary Western tended towards down-in-the-dust realism over the ensuing years, together with a resolute eschewing of heroism. In fact, there were few tasks the literary Western set about with more vigour than the debunking of the more preposterous illusions fostered about the Wild West – usually by the popular Western itself. Mark Twain got in an early blow with his parody “The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” (1865). In literary hands, the desire to cut down mythology to uncover the real West was simultaneously to uncover a West of paradox and conflict, and of material and psychological hardship. Of diversity, too. Willa Cather, Hamlin Garland, John Steinbeck and Mari Sandoz in taking their sweep of the West’s horizon found their gaze not settling on the cowboy but the sodbusting farmer. A.B. Guthrie created “mountain men” characters for his monumental The Big Sky (1947) and in The Big Rock Candy Mountain (1943) Wallace Stegner, the “dean” of western writers, homed in on townsfolk of the West. Larry McMurtry, for all the success of his cattle-drive epic Lonesome Dove, long specialised in small Western town blues, with the town usually fictionalised as Thalia. When the literary Western looked upon the cowboy, it tended to do so with a distinct, unsettling candour, beginning with Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s The Oxbow Incident in 1948, in which cowboys turn into a lynch-mob. Fifty years or so later, Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain” abolished an Old West cliché (or perhaps a taboo) and explored a love affair between two male cowboys. For none of these writers is the West mere backdrop; it penetrates and shapes their fiction.

The desire of the literary Western to set the record straight also meant that American Indians were honoured much earlier in this branch of the genre. John G. Neihardt’s Indian Tales and Others from 1926 was the pioneering attempt to treat Native Americans seriously. Neihardt, though, was white. Skip forward forty years and Native American writers were writing about the West themselves. The breakthrough moment in the “Native American Renaissance” was the publication of N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn in 1969.

In tandem with the Native American Renaissance, a discernible shift towards the ecological occurred in the literary Western. Here the landmark book was Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975). That the literary Western turned environmental is unsurprising. After all, when the chips are down, the Western is about place – and that place, a wilderness, is deserving of reverence and protection. William Kittredge grew up on an Oregon ranch. On turning over the macho and commercial shibboleths of ranching he found them to ring dangerously hollow, and quit to become a writer whose work pulses with sensitivity to nature. The same can be said of Montana’s Rick Bass. There is the beat too of moral indignation over the despoiling of the pristine environment by oil and lumber companies. The literary Western one might add is thriving because, generally, it is about Now, not Then, the New West rather than the Old West.

If popular Western might be a dying breed – though only the foolhardy should write it off – the literary Western is going from strength to strength.

Of course, classifying Western fiction into “popular” and “literary” is a canyon-sized problem. What about Jack London, one of the most popular authors of all time, but whose stories are often strongly literary and realistic? Popular or literary? Owen Wister? His short Western stories are exercises in irony; on the other hand, it was Wister who, in The Virginian (1902), made the cowboy, instead of the fur-wearing scout, the Western hero sans pareil. Under a thousand different names, The Virginian, toting a six-gun and a code of chivalric honour, rode the range of Western fiction for years thereafter.

For all the difficulties of categorising Westerns, some sort of division is useful to separate out the different types of Western writing because at times their style and emphasis have been so radically different. I have included both types of Western story in this anthology because together they demonstrate the breadth and history of fiction available under that tantalizing signpost “Western”.

And now, as they say, dear reader, “Once Upon A Time in the West . . .”

FRANCIS BRET HARTE (1836–1902) was born in New York, but later moved to California, where he worked as a schoolteacher, journalist and typesetter. His literary career took off in 1868, when he became the editor of Overland Monthly. It was in this journal that the tales of the California mining camps which made him famous were first published: “The Luck of Roaring Camp”, “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” and “Tennessee’s Partner”. Few people have been so influential in determining the course of the Western as Harte, since the characters he established in these, and other, stories have since become stock figures in the genre, among them the noble gambler and prostitute with a heart of gold, both of which, for instance, appear in the classic 1939 movie, Stagecoach, directed by John Ford. Harte was also responsible for introducing a certain “upside-down” morality into the Western, since his outcast figures are often morally superior to the supposedly respectable people around them. In mid-career as writer, Harte took a job as an US diplomat in Germany, later moving to London, where he died.

“The Outcasts of Poker Flat” is from 1868. The story has been filmed several times, including by John Ford in 1919.

AS MR JOHN Oakhurst, Gambler, stepped into the main street of Poker Flat on the morning of the twenty-third of November, 1850, he was conscious of a change in its moral atmosphere since the preceding night. Two or three men, conversing earnestly together, ceased as he approached, and exchanged significant glances. There was a Sabbath lull in the air, which, in a settlement unused to Sabbath influences, looked ominous.

Mr Oakhurst’s calm, handsome face betrayed small concern in these indications. Whether he was conscious of any predisposing cause was another question. “I reckon they’re after somebody,” he reflected; “likely it’s me.” He returned to his pocket the handkerchief with which he had been whipping away the red dust of Poker Flat from his neat boots, and quietly discharged his mind of any further conjecture.

In point of fact, Poker Flat was “after somebody”. It had lately suffered the loss of several thousand dollars, two valuable horses, and a prominent citizen. It was experiencing a spasm of virtuous reaction, quite as lawless and ungovernable as any of the acts that had provoked it. A secret committee had determined to rid the town of all improper persons. This was done permanently in regard of two men who were then hanging from the boughs of a sycamore in the gulch, and temporarily in the banishment of certain other objectionable characters. I regret to say that some of these were ladies. It is but due to the sex, however, to state that their impropriety was professional, and it was only in such easily established standards of evil that Poker Flat ventured to sit in judgement.

Mr Oakhurst was right in supposing that he was included in this category. A few of the committee had urged hanging him as a possible example, and a sure method of reimbursing themselves from his pockets of the sums he had won from them. “It’s agin justice,” said Jim Wheeler, “to let this yer young man from Roaring Camp – an entire stranger – carry away our money.” But a crude sentiment of equity residing in the breasts of those who had been fortunate enough to win from Mr Oakhurst overruled this narrower local prejudice.

Mr Oakhurst received his sentence with philosophic calmness, none the less coolly that he was aware of the hesitation of his judges. He was too much of a gambler not to accept Fate. With him life was at best an uncertain game, and he recognized the usual percentage in favour of the dealer.

A body of armed men accompanied the deported wickedness of Poker Flat to the outskirts of the settlement. Besides Mr Oakhurst, who was known to be a coolly desperate man, and for whose intimidation the armed escort was intended, the expatriated party consisted of a young woman familiarly known as “The Duchess”; another, who had won the title of “Mother Shipton”; and “Uncle Billy”, a suspected sluice-robber and confirmed drunkard. The cavalcade provoked no comments from the spectators, nor was any word uttered by the escort. Only when the gulch which marked the uttermost limit of Poker Flat was reached, the leader spoke briefly and to the point. The exiles were forbidden to return at the peril of their lives.

As the escort disappeared, their pent-up feelings found vent in a few hysterical tears from the Duchess, some bad language from Mother Shipton, and a Parthian volley of expletives from Uncle Billy. The philosophic Oakhurst alone remained silent. He listened calmly to Mother Shipton’s desire to cut somebody’s heart out, to the repeated statements of the Duchess that she would die in the road, and to the alarming oaths that seemed to be bumped out of Uncle Billy as he rode forward. With the easy good-humour characteristic of his class, he insisted upon exchanging his own riding-horse, “Five Spot”, for the sorry mule which the Duchess rode. But even this act did not draw the party into any closer sympathy. The young woman readjusted her somewhat draggled plumes with a feeble, faded coquetry; Mother Shipton eyed the possessor of “Five Spot” with malevolence; and Uncle Billy included the whole party in one sweeping anathema.

The road to Sandy Bar – a camp that, not having as yet experienced the regenerating influences of Poker Flat, consequently seemed to offer some invitation to the emigrants – lay over a steep mountain range. It was distant a day’s severe travel. In that advanced season, the party soon passed out of the moist, temperate regions of the foot-hills into the dry, cold, bracing air of the Sierras. The trail was narrow and difficult. At noon the Duchess, rolling out of her saddle upon the ground, declared her intention of going no farther, and the party halted.

The spot was singularly wild and impressive. A wooded amphi-theatre, surrounded on three sides by precipitous cliffs of naked granite, sloped gently toward the crest of another precipice that overlooked the valley. It was, undoubtedly, the most suitable spot for a camp, had camping been advisable. But Mr Oakhurst knew that scarcely half the journey to Sandy Bar was accomplished, and the party were not equipped or provisioned for delay. This fact he pointed out to his companions curtly, with a philosophic commentary on the folly of “throwing up their hand before the game was played out”. But they were furnished with liquor, which in this emergency stood them in place of food, fuel, rest, and prescience. In spite of his remonstrances, it was not long before they were more or less under its influence. Uncle Billy passed rapidly from a bellicose state into one of stupor, the Duchess became maudlin, and Mother Shipton snored. Mr Oakhurst alone remained erect, leaning against a rock, calmly surveying them.

Mr Oakhurst did not drink. It interfered with a profession which required coolness, impassiveness, and presence of mind, and, in his own language, he “couldn’t afford it”. As he gazed at his recumbent fellow-exiles, the loneliness begotten of his pariah-trade, his habits of life, his very vices, for the first time seriously oppressed him. He bestirred himself in dusting his black clothes, washing his hands and face, and other acts characteristic of his studiously neat habits, and for a moment forgot his annoyance. The thought of deserting his weaker and more pitiable companions never perhaps occurred to him. Yet he could not help feeling the want of that excitement which, singularly enough, was most conducive to that calm equanimity for which he was notorious. He looked at the gloomy walls that rose a thousand feet sheer above the circling pines around him: at the sky, ominously clouded; at the valley below, already deepening into shadow. And, doing so, suddenly he heard his own name called.

A horseman slowly ascended the trail. In the fresh, open face of the newcomer Mr Oakhurst recognized Tom Simson, otherwise known as “The Innocent” of Sandy Bar. He had met him some months before over a “little game”, and had, with perfect equanimity, won the entire fortune – amounting to some forty dollars – of that guileless youth. After the game was finished, Mr Oakhurst drew the youthful speculator behind the door, and thus addressed him: “Tommy, you’re a good little man, but you can’t gamble worth a cent. Don’t try it over again.” He then handed him his money back, pushed him gently from the room, and so made a devoted slave of Tom Simson.

There was a remembrance of this in his boyish and enthusiastic greeting of Mr Oakhurst. He had started, he said, to go to Poker Flat to seek his fortune. “Alone?” No, not exactly alone; in fact (a giggle), he had run away with Piney Woods. Didn’t Mr Oakhurst remember Piney? She had used to wait on the table at the Temperance House? They had been engaged a long time, but old Jake Woods had objected, and so they had run away, and were going to Poker Flat to be married, and here they were. And they were tired out, and how lucky it was they had found a place to camp and company. All this the Innocent delivered rapidly, while Piney, a stout, comely damsel of fifteen, emerged from behind the pine-tree, where she had been blushing unseen, and rode to the side of her lover.

Mr Oakhurst seldom troubled himself with sentiment, still less with propriety; but he had a vague idea that the situation was not fortunate. He retained, however, his presence of mind sufficiently to kick Uncle Billy, who was about to say something, and Uncle Billy was sober enough to recognize in Mr Oakhurst’s kick a superior p

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...