- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

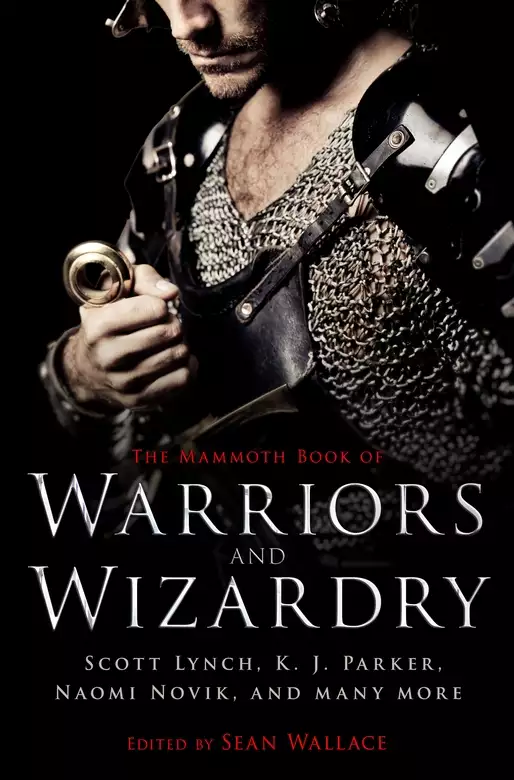

This anthology brings together a stellar collection of short fantasy from authors who have made an impact on the genre over the last decade, along with some bestselling favorites, like Naomi Novik and Jay Lake.

Release date: November 11, 2014

Publisher: Running Press Adult

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Mammoth Book Of Warriors and Wizardry

Sean Wallace

Warriors and wizardry: two of the most enduring and resonant archetypes in fantasy.

The warrior – tracing back to ancient heroes such as Gilgamesh, Arjuna, Beowulf and Gesar, through mid-era institutions like knights, steppe horsemen and samurai, to the modern Western fantasy warrior, in its variants “high” and “low”, Aragorn and Conan. Perhaps it’s a facet of human nature to admire strength and steadfastness. But the warrior archetype also includes everyday figures rising to meet warrior challenges, such as David, Marjuna and Joan of Arc; an earning of the warrior strength and steadfastness through grit and courage.

The wizard seems to represent an opposite: not brawn but brains; not physical strength but mental acumen; knowledge, manifested as corporeal power and often – but not always – wisdom. Perhaps the wizard arises as a synthesis of the supernatural transformations performed by gods in myth and the venerable societal presence of institutions such as shamans, elders and early thinkers, inventors and alchemists; evolving from human figures of myth such as Daedalus, Väinämöinen and Xuanzang as well as sorcerous semi-divine figures such as Hunahpu and Xbalanque, the djinn and Sun Wukong, through Merlin and Morgan le Fay to the modern Western fantasy wizard Gandalf. Perhaps the wizard arises from the facet of human nature to admire knowledge and ability to perform the supernatural, but also to mistrust or fear it.

But as fantasy fiction developed into its own genre, the modern Western forms of warrior and wizard have come to dominate the depiction of these archetypes. Although well known and popular, these narrow representations fail to span the universal variety of these archetypes; the range of cultures and variations in which tales of warriors and wizards have been told – ancient epics of India, China, Mongolia, mid-era sagas of the Mayans, Norse, Finns and Arabia, to name a mere few.

Enter the current fantasy short-fiction movement, with its nuanced focus on character and its eye for diverse takes on archetypes and portrayal of traditionally under-represented cultures and perspectives. The short-fiction format provides the current fantasist with a compact and intensified space in which to present, explore, deconstruct or subvert. The prevalence of these archetypes across human culture provides a rich panoply of warrior and wizard traditions to examine; to use to recast the predominant forms or offer under-represented ones, while at once reveling in the enduring allure that makes these archetypes yet resonant.

The stories in this volume represent the best of this current fantasy short-fiction exploration of universal warriors and wizardry. They are inspired by cultures from around the globe, including medieval Arabia, dynastic Egypt, Imperial China, tribal Europe and feudal Japan, as well as other fantastical worlds that defy categorization. They feature characters of traditionally and non-traditionally represented gender, orientation, origin, society and class. They focus not on these characters’ exploits or might but on their human condition, what it means to be who they are: Yoon Ha Lee’s surgeon who must cut free legendary warriors trapped in the paper of manuscripts, to defend his conquered moon; Benjamin Rosenbaum’s bereaved villager who summons the courage to combat bizarre necromancies in pursuit of the abomination that razed his home; Mary Robinette Kowal’s shaman whose magical power manifests from having his wife strangle him near to death; N. K. Jemisin’s narcomancer, who slips into a land of dreams in order to free the dying from their souls.

Or the stories pair a warrior and a wizard together: Saladin Ahmed’s duo of grumpy old ghost-hunter and earnest young swordsman ascetic; Richard Parks’s duo of world-weary insightful samurai and reprobate priest; Chris Willrich’s duo of thief (a “low” warrior) and poet (what is a poet if not a wizard of words?); Benjanun Sriduangkaew’s dual protagonists not in concert but at odds: an expatriate sorcerer clashing with the warrior sent to arrest her and seize the bones of her dead golem daughter.

All these stories not only offer examinations of varied cultures, nuanced characters, and perspectives both traditionally represented and not, but do it while telling a great tale; entertaining, captivating, moving. They use the warrior and wizard archetypes as a starting point to delve into human culture and investigate the human condition. And, in showing us varied characters and diverse cultures and worlds, also teach us something about ourselves and our own. Which may be the greatest wizardry of all.

Scott H. Andrews Editor-in-Chief, Beneath Ceaseless Skies

The power of an oath, thought Alain, is a terrible thing. Here he was freezing on the northern frontier, a dozen summers from the last days of his youth, bound by two silver pennies pressed into his fist the day he took the Duke of Bourne’s service.

Unlike most soldiers, he still had the pennies, somewhere, as yet unspent on whores or wine.

Alain would probably die here. Everybody had to die somewhere. Alain just wished he had been smart enough to die at home in bed. Where it was warm. Instead of standing brevet corporal to a pair of drunken serjeants, wondering what he would eat during the coming winter. All because he’d sworn by his name, over silver.

“Last supply caravan was, what, eleven months ago?” Serjeant Odilo, who chewed a local weed he claimed granted him visions of paradise, hawked a clustered wad into the dust. His lips were stained deep blue, as if he were a berry farmer forever sampling his crop. Odilo reminded Alain of some ape from the deepest south, cringing with unspoken pain, captive forever in invisible chains of duty.

“Been all four seasons,” said Alain, staring at the clotted indigo wad of spit and leaves. Autumn was drawing to a close. Supply was on the minds of every trooper in the First Century.

Once, the army had seemed better than a narrow life on a little farm with some girl he’d known since childhood. Now, still not even thirty summers old, he felt broken-backed in the Duke’s service. His life had washed him upon this northern shore guarding only seabirds and seals and whatever lurked bright-eyed in the night outside the flickering, fading circle of their watch fires.

The long, narrow harbor below the cliffs on which the soldiers dwelt was beautiful, winter and summer. It never quite froze, because of the warm waters flowing from the smoking flanks of Mount Abaia to the north and east. In winter, snow blanketed the rocky shores and highlighted the struggling firs along the steep cliffs. Summer brought wildflowers like a shattered rainbow, smeared across the earth with a smell of honey and grass so strong as to make the mules mad.

The captain’s theory was that the Duke of Bourne had once meant to keep ships in the harbor, to guard these northern waters, and they, First Century of the Fourth Battle of the IV Legion, were sent to guard the landing from the Ice Tribes in their northern fastness. The subaltern had been silent on the matter since long before Alain arrived, preferring to live alone in the foothills to the east. Odilo and his brother serjeant Severus argued about everything from horses to women to the weather, but they wouldn’t discuss First Century’s years-long deployment either.

“Us as takes the Duke’s coins do His Grace’s bidding,” Odilo was fond of saying over fire and wine. “No questions asked, no duties shirked.”

Alain was hard-pressed to see what duties they might be shirking. The watchtower had been abandoned by the engineers after laying the foundation courses. One old derrick remained, that Alain and some of the other men had restored to working order the previous summer, just for something to do. A few loose blocks of dressed stone inhabited the camp, mostly tables now, that presumably the First of the Fourth were keeping safe from marauders.

Some of the younger men – recruits from the last few waves of reinforcements, including the final squad that had brought Alain four years earlier – liked to say they were there to be trained, strengthened, until they grew to champions to be summoned back to the Duke’s Own Guard clothed in honor and glory. But Alain sometimes found eider-fletched arrows broken in the woods that told him a different story, along with soft-soled prints from shoes worn by no soldier of the Duke.

Alain believed that the absent subaltern trafficked with the Ice Tribes who live to the north, and that the Ice Tribes watched their Century’s little camp. He had never understood what those strange men wanted.

“I saw powerful magic,” said the captain. “Once.”

The First Century gathered around a smoky evening fire, each man’s face flickering into a goblin mask.

“Small magic, too,” the old man continued. “The hardest kind. Anyone with talent can call a storm or set a raging fire, but to hold the flame in your hand, or make the water dance, now that’s rare.”

Odilo smacked his lips, then found his voice. “Begging your pardon, sir, but magic’s mostly good for tearing a man’s guts out and scaring the kiddies into their graves. Nothing but dark purpose, perfect and evil. Can’t fight it, can’t live with it.”

“And there you’re wrong.” The captain’s teeth gleamed yellow in the firelight, shaped by his smile. “Every work of magic has a flaw, a fault, some loophole from perfection. Otherwise the gods would not permit it to be. The greater the work, the greater the flaw, if it can be found. Small magic has small flaws.”

After a moment of fire-crackling silence, the captain con tinued. “It can be of good purpose, too. I saw a wizard on a battlefield down near Southgate, when I was a trooper in the Army of the Black. Light cavalry, my first enlistment, before I was commissioned.

“We swept across a field just before dawn, aiming to get up in some high trees and screen the flank of that day’s advance. There this fellow was on the field below us, his face all aglow like those jellyfish our harbor gets in the spring. My serjeant sent me out of cover to see what the lay was.” The captain’s smile widened. “I was disposable, you might say, in those days.”

The men dutifully laughed.

“Anyway, there this little wizard was, barely tall as my shoulder, in robes I wouldn’t hang on a beggar, and he had a man’s life in his hands.” The captain shook his head. “Don’t know how else to put it.

“He had this little misty ball, no bigger than a child’s head. Though I was on a horse thirty feet away, I could see a whole world inside, a baby in its nappies, a boy plucking apples, dinners and fairs and going for a soldier and his whole life until he was struck down by a spear that previous day on our battlefield.

“So I says to the wizard, ‘What are you about, man? There’ll be killing here soon.’ And he looks at me the way a lamb looks at the slaughterman with the hammer and says with that slippery wizard echo in his voice, ‘If I can only put one back into the world, my victory is still greater than your entire army.’”

The fire crackled for a while, silence of the night the only response to the captain’s story, until Odilo spat again. “Did you run the little sharp-tongue through? Can’t trust them wizards.”

The captain just looked sad, then bid the men good evening and shuffled off to his hut.

“Alain, get up,” hissed Odilo, hitting him again.

Until the frosts came, Alain often forsook the hut he shared with three other soldiers to sleep atop the abandoned foundation courses of the tower. It kept him closer to the stars, and slightly diminished the influence of the blackflies. He hoped.

Alain glared at Odilo through sleep-clouded eyes, seeing dawn’s barest stain above the mountains to the east. “Wha . . . ? I don’ ha’ mornin’ watch.”

“Captain’s dead,” Odilo said quietly. No lip-smacking this morning. “His heart, maybe. Don’t look like he been killed or nothing. But still as a stone, and not much warmer.”

Amid a profound twinge of sadness – no father to his men, still the captain did serve as something of a befuddled uncle – Alain found his voice, and his curiosity. “I’m a brevet corporal, you’re the serjeant. Why are you waking me?”

“I’ve sent a runner south.” Odilo glanced over his shoulder, shaking his head.

Alain understood what he meant – no messages of theirs had been answered for almost a year.

The serjeant returned his glare to Alain. “I need someone to get the subaltern. He’s in command of the Century now. Likely he won’t throw rocks at you.” Odilo’s voice was suddenly low and sly. “You talk to him sometimes. I know it.”

Alain realized Odilo was frightened. Of command? Of being abandoned?

It didn’t matter.

The subaltern would not come, not if the Duke of Bourne himself appeared to deliver the orders in person. The subaltern had fled his life, remaining connected to the Century only by the tenuous thread of habit, and lack of sufficient ambition to move farther inland on his own.

“I’ll go, but he won’t help,” Alain warned, discharging his final duty to the captain in one sentence.

“Someone’s got to do it,” Odilo hissed. Fear leaked from him like steam from a kettle.

Alain said nothing more, but brushed the chilly dew out of his boots with the warm underside of his blanket. Odilo moved off in the morning twilight, adrift, searching for purpose.

There were three eider-fletched arrows in the lintel of the subaltern’s snug little cabin, and the door stood open, badly splintered. Alain jabbed at it with his spear, not afraid of marauders within – had they still been present they would not have let him approach this close – but of what portions of the subaltern might remain behind the door.

The wood creaked wide open, innocent of menace. Alain stepped in, feeling as if he were the barbarian, come to pillage civilization’s last outpost.

Although over time he and the subaltern had exchanged careful, quiet nods in the forests of aspen and birch that lay inland north and east of the Century’s encampment, Alain had in fact never spoken to the officer. As far as he knew, no one had, except possibly the captain. Who had other, more grave concerns to occupy him now.

The cabin was almost spotless inside. The silvery birch floor was polished clean as a deck in the Duke’s fleet – Alain was on a ship once, briefly. Its perfection was marred only by a spray of blood and three fresh cuts.

Blows of an ax, from the look of the thing, Alain told himself.

There was almost no furniture, only a little frame bed slung with knotted ropes, a stool and a tiny table. Leaves, roots and vegetables hung from the ceiling. The embers of a fire still smoked in the little hearth. A flag with the Ducal insignia hung on one wall. Except for the blood and the ax scars, the cabin was unmarred. Unlooted. Intact.

“They took nothing but the subaltern,” Alain whispered to Serjeants Odilo and Severus.

The three of them huddled on a wind-whipped point of rock jutting out over the bay far below. The men called it “The Leap” because every now and then someone did so, launching himself into the next cycle of life with a long, slow dive. It was one of the few places where a conversation could be guaranteed private, as there was no cover anywhere near. A brown gull hung in the wind, eyeing them in hope of fish heads or bread crusts.

“Go to Darknesh,” muttered Severus, long-ago veteran of one of the stranger religions to be found in Bournemouth, with the scars to prove it. His cheeks were flushed, his words already slurred from early drinking.

Odilo glanced from Severus to Alain and back, over and over like a squirrel between two nuts. Odilo would be comical, Alain thought, if not for the desperation in his face.

“We should retreat,” Odilo said, smacking his lips as blue spittle leaked down his chin. “Break the camp, march the Century back to North Coast Keep.”

Ten days’ march south and west, North Coast was where the Fourth Battle had its headquarters. Superior officers, discipline, all the things a good soldier shunned.

But a man wouldn’t have to do his own thinking there. Or bury his own dead.

“North Coasht,” Severus said, then grunted. “Bashtards shor’-measured our oil rash-en lasht year. Never did nothin’ fer ush.”

“Your runner will come back with orders,” Alain said, filled with a sense of urgency, a new-found loyalty to the captain somehow inspired by the dead man’s story about the grubby little wizard on the battlefield. “We should stand with our mission.”

“What mission?” Odilo’s voice peaked in panic before settling into his accustomed jeer. He spat out over the harbor, the brown gull diving after the wadded leaves. “Captain never told us nothing ’cept sit tight. Well, we sat tight. Now you want us to swivel around here on our asses, out of supply, waiting for the snows to come. A couple of weeks, the road back to North Coast will be waist-deep in mud, a couple of weeks after that, snow up to our earlobes. If’n we want to leave, we got to leave now.”

Alain shrugged. “You’re the serjeant. I’m just a corporal.” Afraid to meet Odilo’s eye, he looked out at the gull, returned to hanging in the wind. “But I’m staying.”

The subaltern might need someone to come home to, even if he came in small pieces.

The First Century decided to bury their captain that coming evening, on the south side of their camp. The warm side. There was a squabble when no one could find the banners. Alain knew the Ducal standard was at the subaltern’s cabin, but he kept his mouth shut, praying for the little wizard to come before cold dirt and pine needles filled the captain’s face forever.

Each man in the Century dug at least a shovelful from the grave, which resulted in a scooped-out bowl in the soil. It was a kind thought, but Alain hated the shallow pit that was created, so he stripped to his trousers and dug the grave properly from the bottom of the pit, working with a fury born of frustration. It made for a huge trench. Exhausted, he finally climbed out.

“Planning to lay us all in the ground together?” Odilo asked as Alain cleaned the shovel and gathered his clothing.

Alain tried to smile. “A great man deserves a great grave.”

Odilo spat. “He wasn’t a great man. He was a jumped-up clerk turned out to fight in some war what couldn’t get his old job back after. They kept him around and made him an officer ’cause he could read and write.”

Alain could read and write, some – his childhood village had had a progressive priest who served a gentle god – but this didn’t seem the time to mention that. “He was great to me,” said Alain, thinking again of the grubby little wizard and the small magic of restoring a man’s life.

* * *

When First Century marched out of their camp to lay the body to rest, wrapped in a sheet from the captain’s cot, they found another eider-fletched arrow. This one was point down in the bottom of the grave, still quivering, though no one saw it fly and the woods were hundreds of yards away.

Without a word, Alain scrambled down into the grave, plucked the arrow from the turned earth, snapped it in two and climbed back out to lay the halves atop the captain’s winding sheet. The men of the Century cheered, even Serjeant Severus. Then they rushed through the funeral, each eager to get to serious drinking and plotting their escape from this northern perdition.

The little wizard never came.

In the morning, eight men were gone, with their gear and somehow – against all common sense where the noisy beasts were concerned – one of the camp mules. Serjeant Severus was also among the missing, though his gear was still present.

Odilo would send no one after the deserters, but was willing to turn out a desultory search effort for Severus. Alain went to The Leap, where he spotted Severus floating in the bay far below.

At least he assumed it was Severus. A man was there, wrapped in an old tunic the color of bayberries, just as Severus wore lounging around the camp. His head seemed to be missing, although perhaps Severus was simply riding low in the water.

After some thought, Alain told Serjeant Odilo.

“Quiet, fool,” Odilo said, smacking his lips. He had been chewing his weed like a mule ate hay, this last day or so. “Let the men search. I’ll prepare our withdrawal.”

Alain was overcome with a wave of stubborn pride. “So when Benno and Faubus and the others left, it was desertion, but now we’re going to withdraw?”

“This is orders,” Odilo said, pressing his puffy, blue-stained nose right into Alain’s face.

“We already have orders, serjeant.”

“You want to stay here and die at the hands of the Ice Tribes, fine with me. You’ve got Severus’s squads now, corporal. Orders is half yours.” Odilo spat between Alain’s feet, then stalked away.

The Century’s encampment surrounded the foundation courses of the unfinished tower. They were protected on three sides by wooden hoardings backed with clay, erected years before in best army fashion, though these were now mostly overgrown with beans and melon vines. Fields of hardy crops stretched around the hoardings. The fourth side was open to the cliff over the water, with gaps between the ends of the hoardings and the cliff large enough to drive a wagon through at each end.

First Century even had an old cannon, a lion-mouthed thing originally captured from the Onyx Navy far to the near-mythical south. It was spoil of some battle, handed from unit to unit and officer to officer until like the men it had finally washed up here on this northmost shore. There was a small pile of shot, rusted together, and four kegs of what was alleged to be powder, though no one in the Century seemed to know what to do with the stuff.

Alain organized some of the younger men to wrestle the cannon into the inland-facing gap between the hoarding and the cliff. He readied one of the unit’s two wagons to block the other gap, while Serjeant Odilo supervised a loading up of the second wagon for the march south.

Neither of them had actually issued orders. Rather, each quietly made his intentions known, and some silent democracy of soldiers voted in successive pairs of booted feet, until the Century had divided itself around two heads, like a worm cut in half and left to regrow.

It was no surprise to Alain that most of Odilo’s men chose to go with the serjeant, while most of Severus’s men stayed with him. Alain was polite enough to leave Odilo’s way clear. Odilo was smart enough not to comment on the folly of Alain’s cannon.

Late that afternoon, as the Southron cannon was mounted in place and the departing wagon had been fully loaded, a rider appeared out of the trees a quarter mile inland, to the east. He was a small man on a small horse, the animal grubby white with shaggy hair, the man grubby brown wrapped in shaggy furs.

Alain and Odilo found themselves side-by-side at the east-facing hoarding. The weather had turned suddenly colder and damper, and their breath curled and mingled together, nature seeking to reunite the Century by some sympathetic magic.

“What do you think?” Odilo finally asked as the rider approached at an insolently slow canter.

“I don’t know yet,” Alain said, looking carefully to see if any heads were dangling from the rider’s saddle.

The newcomer carried a tall pole with a small wooden circle or wheel mounted across the top, from which dangled a forest of dark horsetails. He was clad entirely in furs, only his face visible, which glistened with smeared-on fat.

“Hai,” said the rider.

“What’s your business here?” Odilo demanded.

“I’ve come to ease your sorry lives,” the rider said in astonishingly good Wentish, the language of the duchy.

A herald of sorts, then, Alain thought.

“The chief of our chiefs requires this place for his use,” the rider went on. “You are invited to depart before his armies come scouring.”

“I—” Odilo began to say, but Alain elbowed him in the ribs and spoke over him. “The Duke’s army moves at no one’s beck save His Grace’s own.”

“You do not need this place,” said the rider. “Your men do nothing here but grow fat and tired. Go south, to your warmlands and your women, and leave our cold places to us.”

“Fat and tired we may be, but here we’ll stay,” Alain shouted. “Now begone and tell your little chief we will not surrender to him.”

“Nobody said nothing about surrendering,” Odilo muttered in a pained voice, but the rider was already cantering away.

That night around the fires, the silent democracy of soldiers finally found its voice. “We’ll all die here – for what?” “They killed the captain, too, some ice wizard’s work.” “Magicked the subaltern years ago.” “Eating Serjeant Severus’s liver even now, I warrant you.” “That Alain’s crazy, and too big for his boots.” “Odilo’s a coward – we got a job to do.”

At dawn the loaded wagon creaked away west and south, accompanied by the irritated complaints of mules, the shuffling of dozens of feet and one spitting serjeant. Alain stood atop his lion-mouthed cannon, facing northeast where the enemy doubtless waited, wondering what had ever possessed him to stay.

After the sun had broken above the shoulder of Mount Abaia into an icy clear day, Alain turned to find that over half the Century had stayed with him.

“Well,” he said, “pull that last wagon around to block the other exit, and let’s have men on the hoardings. A show of strength is what’s called for here, and a show of strength is what we’ll have.”

As they bustled to their work, Alain again felt pride in being a soldier, for the first time in years. He recalled the Ducal standard in the subaltern’s cabin. “I’m off to scout a bit. Hold fast, and see if some one of you can’t manage to load this cannon up.”

The men of the Century cheered as Alain walked into the woods, toward their enemy.

He found the cabin without challenge – there were no Ice Tribesmen in evidence. The arrows were gone and the door was shut, but Alain simply pushed in.

The flag was still there, but so was a large man in furs. Enormous, in fact, for an Ice Tribesman. His resemblance to the herald was passing at best, bald head tattooed with runes, a necklace of fingerbones around his neck. He sat on the subaltern’s lone stool, staring at Alain with an expression of mild amusement that broadened to a yellow-toothed grin.

“You’re their shaman,” Alain said without preamble, ignoring the chill stab of fear in his heart. He was careful not to make any quick motions with his spear.

“How tell?” asked the tribesman in thickly accented Wentish. His voice was a braying rasp, with a strange echo underneath as if he spoke from two places at once. What the captain had called “a slippery wizard echo”.

“Who else would be in here? And someone killed the captain.” Alain leaned his spear against the doorpost. “Besides, you’ve got charms and fetishes.”

“All Ice Tribe got charm fetish,” said the shaman. “Big power, big pain. You go home now.”

“This is my home. His Grace told me to come live here, and here I live.” Well, actually, some clerk had told him, but it was the Duke’s will, however indirect.

“Big magic in north. Big working, go home, danger you.” The shaman mimed fangs and snarled. “Call snow demon, steal you heart. Many rider cross you grave. You go now, you safe.”

Demons. The Ice Tribes were going to summon demons and bring their armies rampaging southward. The chill stab in his heart twinged again, the ordinary private magic of fear. His own death was close at hand, and the death of thousands more if the tribes swept southward behind their demons.

All the more reason to stand fast, to show the Ice Tribes that the Duke’s men were brave and true.

Alain recalled the captain’s story of the grubby little wizard and his small magic. “Big magic, sure. Call lightning. Send us storms. I’ve no doubt your snow demons could eat us like sausages.” He stepped past the shaman, pulled the Ducal standard down from the wall. “We have some small magic of our own, oaths and loyalty. And I know a secret about small magic and big magic.”

With that, Alain nodded at the shaman, wrapped the flag over one arm, took up his spear again and left. He saw no one on the walk back to the encampment, but he hadn’t really expected to.

At the walls, the men were pointing to a wispy thread of smoke in the distance, far to the southwest along the coast. Alain knew it had to be Odilo’s wagon burning, the serjeant and his men as dead as Severus and the captain, but he just shrugged when the younger men asked him what the fire might mean.

The older men looked grim and said nothing.

“Me, I was a sailor betimes,” Michel said to Alain out of the corner of his mouth later that day.

Alain was fascinated. Was this fantasy, or secret history? Michel was a little man with a Southgate accent who’d never had much to say. “We’ve both lived in this place for four years,” Alain said. “This is the first time you’ve brought that up.”

“Jumped ship,” Michel said. “Land is safer, always.”

Even now? Alain wondered, but he did not say it. Instead, he waved at the lion-mouthed cannon, glowering in ancient, corroded brass. “You ever fire

The warrior – tracing back to ancient heroes such as Gilgamesh, Arjuna, Beowulf and Gesar, through mid-era institutions like knights, steppe horsemen and samurai, to the modern Western fantasy warrior, in its variants “high” and “low”, Aragorn and Conan. Perhaps it’s a facet of human nature to admire strength and steadfastness. But the warrior archetype also includes everyday figures rising to meet warrior challenges, such as David, Marjuna and Joan of Arc; an earning of the warrior strength and steadfastness through grit and courage.

The wizard seems to represent an opposite: not brawn but brains; not physical strength but mental acumen; knowledge, manifested as corporeal power and often – but not always – wisdom. Perhaps the wizard arises as a synthesis of the supernatural transformations performed by gods in myth and the venerable societal presence of institutions such as shamans, elders and early thinkers, inventors and alchemists; evolving from human figures of myth such as Daedalus, Väinämöinen and Xuanzang as well as sorcerous semi-divine figures such as Hunahpu and Xbalanque, the djinn and Sun Wukong, through Merlin and Morgan le Fay to the modern Western fantasy wizard Gandalf. Perhaps the wizard arises from the facet of human nature to admire knowledge and ability to perform the supernatural, but also to mistrust or fear it.

But as fantasy fiction developed into its own genre, the modern Western forms of warrior and wizard have come to dominate the depiction of these archetypes. Although well known and popular, these narrow representations fail to span the universal variety of these archetypes; the range of cultures and variations in which tales of warriors and wizards have been told – ancient epics of India, China, Mongolia, mid-era sagas of the Mayans, Norse, Finns and Arabia, to name a mere few.

Enter the current fantasy short-fiction movement, with its nuanced focus on character and its eye for diverse takes on archetypes and portrayal of traditionally under-represented cultures and perspectives. The short-fiction format provides the current fantasist with a compact and intensified space in which to present, explore, deconstruct or subvert. The prevalence of these archetypes across human culture provides a rich panoply of warrior and wizard traditions to examine; to use to recast the predominant forms or offer under-represented ones, while at once reveling in the enduring allure that makes these archetypes yet resonant.

The stories in this volume represent the best of this current fantasy short-fiction exploration of universal warriors and wizardry. They are inspired by cultures from around the globe, including medieval Arabia, dynastic Egypt, Imperial China, tribal Europe and feudal Japan, as well as other fantastical worlds that defy categorization. They feature characters of traditionally and non-traditionally represented gender, orientation, origin, society and class. They focus not on these characters’ exploits or might but on their human condition, what it means to be who they are: Yoon Ha Lee’s surgeon who must cut free legendary warriors trapped in the paper of manuscripts, to defend his conquered moon; Benjamin Rosenbaum’s bereaved villager who summons the courage to combat bizarre necromancies in pursuit of the abomination that razed his home; Mary Robinette Kowal’s shaman whose magical power manifests from having his wife strangle him near to death; N. K. Jemisin’s narcomancer, who slips into a land of dreams in order to free the dying from their souls.

Or the stories pair a warrior and a wizard together: Saladin Ahmed’s duo of grumpy old ghost-hunter and earnest young swordsman ascetic; Richard Parks’s duo of world-weary insightful samurai and reprobate priest; Chris Willrich’s duo of thief (a “low” warrior) and poet (what is a poet if not a wizard of words?); Benjanun Sriduangkaew’s dual protagonists not in concert but at odds: an expatriate sorcerer clashing with the warrior sent to arrest her and seize the bones of her dead golem daughter.

All these stories not only offer examinations of varied cultures, nuanced characters, and perspectives both traditionally represented and not, but do it while telling a great tale; entertaining, captivating, moving. They use the warrior and wizard archetypes as a starting point to delve into human culture and investigate the human condition. And, in showing us varied characters and diverse cultures and worlds, also teach us something about ourselves and our own. Which may be the greatest wizardry of all.

Scott H. Andrews Editor-in-Chief, Beneath Ceaseless Skies

The power of an oath, thought Alain, is a terrible thing. Here he was freezing on the northern frontier, a dozen summers from the last days of his youth, bound by two silver pennies pressed into his fist the day he took the Duke of Bourne’s service.

Unlike most soldiers, he still had the pennies, somewhere, as yet unspent on whores or wine.

Alain would probably die here. Everybody had to die somewhere. Alain just wished he had been smart enough to die at home in bed. Where it was warm. Instead of standing brevet corporal to a pair of drunken serjeants, wondering what he would eat during the coming winter. All because he’d sworn by his name, over silver.

“Last supply caravan was, what, eleven months ago?” Serjeant Odilo, who chewed a local weed he claimed granted him visions of paradise, hawked a clustered wad into the dust. His lips were stained deep blue, as if he were a berry farmer forever sampling his crop. Odilo reminded Alain of some ape from the deepest south, cringing with unspoken pain, captive forever in invisible chains of duty.

“Been all four seasons,” said Alain, staring at the clotted indigo wad of spit and leaves. Autumn was drawing to a close. Supply was on the minds of every trooper in the First Century.

Once, the army had seemed better than a narrow life on a little farm with some girl he’d known since childhood. Now, still not even thirty summers old, he felt broken-backed in the Duke’s service. His life had washed him upon this northern shore guarding only seabirds and seals and whatever lurked bright-eyed in the night outside the flickering, fading circle of their watch fires.

The long, narrow harbor below the cliffs on which the soldiers dwelt was beautiful, winter and summer. It never quite froze, because of the warm waters flowing from the smoking flanks of Mount Abaia to the north and east. In winter, snow blanketed the rocky shores and highlighted the struggling firs along the steep cliffs. Summer brought wildflowers like a shattered rainbow, smeared across the earth with a smell of honey and grass so strong as to make the mules mad.

The captain’s theory was that the Duke of Bourne had once meant to keep ships in the harbor, to guard these northern waters, and they, First Century of the Fourth Battle of the IV Legion, were sent to guard the landing from the Ice Tribes in their northern fastness. The subaltern had been silent on the matter since long before Alain arrived, preferring to live alone in the foothills to the east. Odilo and his brother serjeant Severus argued about everything from horses to women to the weather, but they wouldn’t discuss First Century’s years-long deployment either.

“Us as takes the Duke’s coins do His Grace’s bidding,” Odilo was fond of saying over fire and wine. “No questions asked, no duties shirked.”

Alain was hard-pressed to see what duties they might be shirking. The watchtower had been abandoned by the engineers after laying the foundation courses. One old derrick remained, that Alain and some of the other men had restored to working order the previous summer, just for something to do. A few loose blocks of dressed stone inhabited the camp, mostly tables now, that presumably the First of the Fourth were keeping safe from marauders.

Some of the younger men – recruits from the last few waves of reinforcements, including the final squad that had brought Alain four years earlier – liked to say they were there to be trained, strengthened, until they grew to champions to be summoned back to the Duke’s Own Guard clothed in honor and glory. But Alain sometimes found eider-fletched arrows broken in the woods that told him a different story, along with soft-soled prints from shoes worn by no soldier of the Duke.

Alain believed that the absent subaltern trafficked with the Ice Tribes who live to the north, and that the Ice Tribes watched their Century’s little camp. He had never understood what those strange men wanted.

“I saw powerful magic,” said the captain. “Once.”

The First Century gathered around a smoky evening fire, each man’s face flickering into a goblin mask.

“Small magic, too,” the old man continued. “The hardest kind. Anyone with talent can call a storm or set a raging fire, but to hold the flame in your hand, or make the water dance, now that’s rare.”

Odilo smacked his lips, then found his voice. “Begging your pardon, sir, but magic’s mostly good for tearing a man’s guts out and scaring the kiddies into their graves. Nothing but dark purpose, perfect and evil. Can’t fight it, can’t live with it.”

“And there you’re wrong.” The captain’s teeth gleamed yellow in the firelight, shaped by his smile. “Every work of magic has a flaw, a fault, some loophole from perfection. Otherwise the gods would not permit it to be. The greater the work, the greater the flaw, if it can be found. Small magic has small flaws.”

After a moment of fire-crackling silence, the captain con tinued. “It can be of good purpose, too. I saw a wizard on a battlefield down near Southgate, when I was a trooper in the Army of the Black. Light cavalry, my first enlistment, before I was commissioned.

“We swept across a field just before dawn, aiming to get up in some high trees and screen the flank of that day’s advance. There this fellow was on the field below us, his face all aglow like those jellyfish our harbor gets in the spring. My serjeant sent me out of cover to see what the lay was.” The captain’s smile widened. “I was disposable, you might say, in those days.”

The men dutifully laughed.

“Anyway, there this little wizard was, barely tall as my shoulder, in robes I wouldn’t hang on a beggar, and he had a man’s life in his hands.” The captain shook his head. “Don’t know how else to put it.

“He had this little misty ball, no bigger than a child’s head. Though I was on a horse thirty feet away, I could see a whole world inside, a baby in its nappies, a boy plucking apples, dinners and fairs and going for a soldier and his whole life until he was struck down by a spear that previous day on our battlefield.

“So I says to the wizard, ‘What are you about, man? There’ll be killing here soon.’ And he looks at me the way a lamb looks at the slaughterman with the hammer and says with that slippery wizard echo in his voice, ‘If I can only put one back into the world, my victory is still greater than your entire army.’”

The fire crackled for a while, silence of the night the only response to the captain’s story, until Odilo spat again. “Did you run the little sharp-tongue through? Can’t trust them wizards.”

The captain just looked sad, then bid the men good evening and shuffled off to his hut.

“Alain, get up,” hissed Odilo, hitting him again.

Until the frosts came, Alain often forsook the hut he shared with three other soldiers to sleep atop the abandoned foundation courses of the tower. It kept him closer to the stars, and slightly diminished the influence of the blackflies. He hoped.

Alain glared at Odilo through sleep-clouded eyes, seeing dawn’s barest stain above the mountains to the east. “Wha . . . ? I don’ ha’ mornin’ watch.”

“Captain’s dead,” Odilo said quietly. No lip-smacking this morning. “His heart, maybe. Don’t look like he been killed or nothing. But still as a stone, and not much warmer.”

Amid a profound twinge of sadness – no father to his men, still the captain did serve as something of a befuddled uncle – Alain found his voice, and his curiosity. “I’m a brevet corporal, you’re the serjeant. Why are you waking me?”

“I’ve sent a runner south.” Odilo glanced over his shoulder, shaking his head.

Alain understood what he meant – no messages of theirs had been answered for almost a year.

The serjeant returned his glare to Alain. “I need someone to get the subaltern. He’s in command of the Century now. Likely he won’t throw rocks at you.” Odilo’s voice was suddenly low and sly. “You talk to him sometimes. I know it.”

Alain realized Odilo was frightened. Of command? Of being abandoned?

It didn’t matter.

The subaltern would not come, not if the Duke of Bourne himself appeared to deliver the orders in person. The subaltern had fled his life, remaining connected to the Century only by the tenuous thread of habit, and lack of sufficient ambition to move farther inland on his own.

“I’ll go, but he won’t help,” Alain warned, discharging his final duty to the captain in one sentence.

“Someone’s got to do it,” Odilo hissed. Fear leaked from him like steam from a kettle.

Alain said nothing more, but brushed the chilly dew out of his boots with the warm underside of his blanket. Odilo moved off in the morning twilight, adrift, searching for purpose.

There were three eider-fletched arrows in the lintel of the subaltern’s snug little cabin, and the door stood open, badly splintered. Alain jabbed at it with his spear, not afraid of marauders within – had they still been present they would not have let him approach this close – but of what portions of the subaltern might remain behind the door.

The wood creaked wide open, innocent of menace. Alain stepped in, feeling as if he were the barbarian, come to pillage civilization’s last outpost.

Although over time he and the subaltern had exchanged careful, quiet nods in the forests of aspen and birch that lay inland north and east of the Century’s encampment, Alain had in fact never spoken to the officer. As far as he knew, no one had, except possibly the captain. Who had other, more grave concerns to occupy him now.

The cabin was almost spotless inside. The silvery birch floor was polished clean as a deck in the Duke’s fleet – Alain was on a ship once, briefly. Its perfection was marred only by a spray of blood and three fresh cuts.

Blows of an ax, from the look of the thing, Alain told himself.

There was almost no furniture, only a little frame bed slung with knotted ropes, a stool and a tiny table. Leaves, roots and vegetables hung from the ceiling. The embers of a fire still smoked in the little hearth. A flag with the Ducal insignia hung on one wall. Except for the blood and the ax scars, the cabin was unmarred. Unlooted. Intact.

“They took nothing but the subaltern,” Alain whispered to Serjeants Odilo and Severus.

The three of them huddled on a wind-whipped point of rock jutting out over the bay far below. The men called it “The Leap” because every now and then someone did so, launching himself into the next cycle of life with a long, slow dive. It was one of the few places where a conversation could be guaranteed private, as there was no cover anywhere near. A brown gull hung in the wind, eyeing them in hope of fish heads or bread crusts.

“Go to Darknesh,” muttered Severus, long-ago veteran of one of the stranger religions to be found in Bournemouth, with the scars to prove it. His cheeks were flushed, his words already slurred from early drinking.

Odilo glanced from Severus to Alain and back, over and over like a squirrel between two nuts. Odilo would be comical, Alain thought, if not for the desperation in his face.

“We should retreat,” Odilo said, smacking his lips as blue spittle leaked down his chin. “Break the camp, march the Century back to North Coast Keep.”

Ten days’ march south and west, North Coast was where the Fourth Battle had its headquarters. Superior officers, discipline, all the things a good soldier shunned.

But a man wouldn’t have to do his own thinking there. Or bury his own dead.

“North Coasht,” Severus said, then grunted. “Bashtards shor’-measured our oil rash-en lasht year. Never did nothin’ fer ush.”

“Your runner will come back with orders,” Alain said, filled with a sense of urgency, a new-found loyalty to the captain somehow inspired by the dead man’s story about the grubby little wizard on the battlefield. “We should stand with our mission.”

“What mission?” Odilo’s voice peaked in panic before settling into his accustomed jeer. He spat out over the harbor, the brown gull diving after the wadded leaves. “Captain never told us nothing ’cept sit tight. Well, we sat tight. Now you want us to swivel around here on our asses, out of supply, waiting for the snows to come. A couple of weeks, the road back to North Coast will be waist-deep in mud, a couple of weeks after that, snow up to our earlobes. If’n we want to leave, we got to leave now.”

Alain shrugged. “You’re the serjeant. I’m just a corporal.” Afraid to meet Odilo’s eye, he looked out at the gull, returned to hanging in the wind. “But I’m staying.”

The subaltern might need someone to come home to, even if he came in small pieces.

The First Century decided to bury their captain that coming evening, on the south side of their camp. The warm side. There was a squabble when no one could find the banners. Alain knew the Ducal standard was at the subaltern’s cabin, but he kept his mouth shut, praying for the little wizard to come before cold dirt and pine needles filled the captain’s face forever.

Each man in the Century dug at least a shovelful from the grave, which resulted in a scooped-out bowl in the soil. It was a kind thought, but Alain hated the shallow pit that was created, so he stripped to his trousers and dug the grave properly from the bottom of the pit, working with a fury born of frustration. It made for a huge trench. Exhausted, he finally climbed out.

“Planning to lay us all in the ground together?” Odilo asked as Alain cleaned the shovel and gathered his clothing.

Alain tried to smile. “A great man deserves a great grave.”

Odilo spat. “He wasn’t a great man. He was a jumped-up clerk turned out to fight in some war what couldn’t get his old job back after. They kept him around and made him an officer ’cause he could read and write.”

Alain could read and write, some – his childhood village had had a progressive priest who served a gentle god – but this didn’t seem the time to mention that. “He was great to me,” said Alain, thinking again of the grubby little wizard and the small magic of restoring a man’s life.

* * *

When First Century marched out of their camp to lay the body to rest, wrapped in a sheet from the captain’s cot, they found another eider-fletched arrow. This one was point down in the bottom of the grave, still quivering, though no one saw it fly and the woods were hundreds of yards away.

Without a word, Alain scrambled down into the grave, plucked the arrow from the turned earth, snapped it in two and climbed back out to lay the halves atop the captain’s winding sheet. The men of the Century cheered, even Serjeant Severus. Then they rushed through the funeral, each eager to get to serious drinking and plotting their escape from this northern perdition.

The little wizard never came.

In the morning, eight men were gone, with their gear and somehow – against all common sense where the noisy beasts were concerned – one of the camp mules. Serjeant Severus was also among the missing, though his gear was still present.

Odilo would send no one after the deserters, but was willing to turn out a desultory search effort for Severus. Alain went to The Leap, where he spotted Severus floating in the bay far below.

At least he assumed it was Severus. A man was there, wrapped in an old tunic the color of bayberries, just as Severus wore lounging around the camp. His head seemed to be missing, although perhaps Severus was simply riding low in the water.

After some thought, Alain told Serjeant Odilo.

“Quiet, fool,” Odilo said, smacking his lips. He had been chewing his weed like a mule ate hay, this last day or so. “Let the men search. I’ll prepare our withdrawal.”

Alain was overcome with a wave of stubborn pride. “So when Benno and Faubus and the others left, it was desertion, but now we’re going to withdraw?”

“This is orders,” Odilo said, pressing his puffy, blue-stained nose right into Alain’s face.

“We already have orders, serjeant.”

“You want to stay here and die at the hands of the Ice Tribes, fine with me. You’ve got Severus’s squads now, corporal. Orders is half yours.” Odilo spat between Alain’s feet, then stalked away.

The Century’s encampment surrounded the foundation courses of the unfinished tower. They were protected on three sides by wooden hoardings backed with clay, erected years before in best army fashion, though these were now mostly overgrown with beans and melon vines. Fields of hardy crops stretched around the hoardings. The fourth side was open to the cliff over the water, with gaps between the ends of the hoardings and the cliff large enough to drive a wagon through at each end.

First Century even had an old cannon, a lion-mouthed thing originally captured from the Onyx Navy far to the near-mythical south. It was spoil of some battle, handed from unit to unit and officer to officer until like the men it had finally washed up here on this northmost shore. There was a small pile of shot, rusted together, and four kegs of what was alleged to be powder, though no one in the Century seemed to know what to do with the stuff.

Alain organized some of the younger men to wrestle the cannon into the inland-facing gap between the hoarding and the cliff. He readied one of the unit’s two wagons to block the other gap, while Serjeant Odilo supervised a loading up of the second wagon for the march south.

Neither of them had actually issued orders. Rather, each quietly made his intentions known, and some silent democracy of soldiers voted in successive pairs of booted feet, until the Century had divided itself around two heads, like a worm cut in half and left to regrow.

It was no surprise to Alain that most of Odilo’s men chose to go with the serjeant, while most of Severus’s men stayed with him. Alain was polite enough to leave Odilo’s way clear. Odilo was smart enough not to comment on the folly of Alain’s cannon.

Late that afternoon, as the Southron cannon was mounted in place and the departing wagon had been fully loaded, a rider appeared out of the trees a quarter mile inland, to the east. He was a small man on a small horse, the animal grubby white with shaggy hair, the man grubby brown wrapped in shaggy furs.

Alain and Odilo found themselves side-by-side at the east-facing hoarding. The weather had turned suddenly colder and damper, and their breath curled and mingled together, nature seeking to reunite the Century by some sympathetic magic.

“What do you think?” Odilo finally asked as the rider approached at an insolently slow canter.

“I don’t know yet,” Alain said, looking carefully to see if any heads were dangling from the rider’s saddle.

The newcomer carried a tall pole with a small wooden circle or wheel mounted across the top, from which dangled a forest of dark horsetails. He was clad entirely in furs, only his face visible, which glistened with smeared-on fat.

“Hai,” said the rider.

“What’s your business here?” Odilo demanded.

“I’ve come to ease your sorry lives,” the rider said in astonishingly good Wentish, the language of the duchy.

A herald of sorts, then, Alain thought.

“The chief of our chiefs requires this place for his use,” the rider went on. “You are invited to depart before his armies come scouring.”

“I—” Odilo began to say, but Alain elbowed him in the ribs and spoke over him. “The Duke’s army moves at no one’s beck save His Grace’s own.”

“You do not need this place,” said the rider. “Your men do nothing here but grow fat and tired. Go south, to your warmlands and your women, and leave our cold places to us.”

“Fat and tired we may be, but here we’ll stay,” Alain shouted. “Now begone and tell your little chief we will not surrender to him.”

“Nobody said nothing about surrendering,” Odilo muttered in a pained voice, but the rider was already cantering away.

That night around the fires, the silent democracy of soldiers finally found its voice. “We’ll all die here – for what?” “They killed the captain, too, some ice wizard’s work.” “Magicked the subaltern years ago.” “Eating Serjeant Severus’s liver even now, I warrant you.” “That Alain’s crazy, and too big for his boots.” “Odilo’s a coward – we got a job to do.”

At dawn the loaded wagon creaked away west and south, accompanied by the irritated complaints of mules, the shuffling of dozens of feet and one spitting serjeant. Alain stood atop his lion-mouthed cannon, facing northeast where the enemy doubtless waited, wondering what had ever possessed him to stay.

After the sun had broken above the shoulder of Mount Abaia into an icy clear day, Alain turned to find that over half the Century had stayed with him.

“Well,” he said, “pull that last wagon around to block the other exit, and let’s have men on the hoardings. A show of strength is what’s called for here, and a show of strength is what we’ll have.”

As they bustled to their work, Alain again felt pride in being a soldier, for the first time in years. He recalled the Ducal standard in the subaltern’s cabin. “I’m off to scout a bit. Hold fast, and see if some one of you can’t manage to load this cannon up.”

The men of the Century cheered as Alain walked into the woods, toward their enemy.

He found the cabin without challenge – there were no Ice Tribesmen in evidence. The arrows were gone and the door was shut, but Alain simply pushed in.

The flag was still there, but so was a large man in furs. Enormous, in fact, for an Ice Tribesman. His resemblance to the herald was passing at best, bald head tattooed with runes, a necklace of fingerbones around his neck. He sat on the subaltern’s lone stool, staring at Alain with an expression of mild amusement that broadened to a yellow-toothed grin.

“You’re their shaman,” Alain said without preamble, ignoring the chill stab of fear in his heart. He was careful not to make any quick motions with his spear.

“How tell?” asked the tribesman in thickly accented Wentish. His voice was a braying rasp, with a strange echo underneath as if he spoke from two places at once. What the captain had called “a slippery wizard echo”.

“Who else would be in here? And someone killed the captain.” Alain leaned his spear against the doorpost. “Besides, you’ve got charms and fetishes.”

“All Ice Tribe got charm fetish,” said the shaman. “Big power, big pain. You go home now.”

“This is my home. His Grace told me to come live here, and here I live.” Well, actually, some clerk had told him, but it was the Duke’s will, however indirect.

“Big magic in north. Big working, go home, danger you.” The shaman mimed fangs and snarled. “Call snow demon, steal you heart. Many rider cross you grave. You go now, you safe.”

Demons. The Ice Tribes were going to summon demons and bring their armies rampaging southward. The chill stab in his heart twinged again, the ordinary private magic of fear. His own death was close at hand, and the death of thousands more if the tribes swept southward behind their demons.

All the more reason to stand fast, to show the Ice Tribes that the Duke’s men were brave and true.

Alain recalled the captain’s story of the grubby little wizard and his small magic. “Big magic, sure. Call lightning. Send us storms. I’ve no doubt your snow demons could eat us like sausages.” He stepped past the shaman, pulled the Ducal standard down from the wall. “We have some small magic of our own, oaths and loyalty. And I know a secret about small magic and big magic.”

With that, Alain nodded at the shaman, wrapped the flag over one arm, took up his spear again and left. He saw no one on the walk back to the encampment, but he hadn’t really expected to.

At the walls, the men were pointing to a wispy thread of smoke in the distance, far to the southwest along the coast. Alain knew it had to be Odilo’s wagon burning, the serjeant and his men as dead as Severus and the captain, but he just shrugged when the younger men asked him what the fire might mean.

The older men looked grim and said nothing.

“Me, I was a sailor betimes,” Michel said to Alain out of the corner of his mouth later that day.

Alain was fascinated. Was this fantasy, or secret history? Michel was a little man with a Southgate accent who’d never had much to say. “We’ve both lived in this place for four years,” Alain said. “This is the first time you’ve brought that up.”

“Jumped ship,” Michel said. “Land is safer, always.”

Even now? Alain wondered, but he did not say it. Instead, he waved at the lion-mouthed cannon, glowering in ancient, corroded brass. “You ever fire

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

The Mammoth Book Of Warriors and Wizardry

Sean Wallace

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved