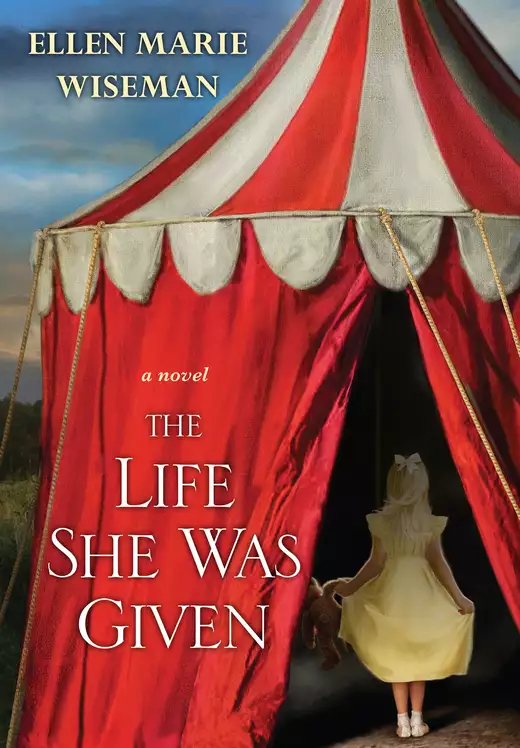

The Life She Was Given

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From acclaimed author Ellen Marie Wiseman comes a vivid, daring novel about the devastating power of family secrets - beginning in the poignant, lurid world of a Depression-era traveling circus and coming full circle in the transformative 1950s.

On a summer evening in 1931, Lilly Blackwood glimpses circus lights from the grimy window of her attic bedroom. Lilly isn't allowed to explore the meadows around Blackwood Manor. She's never even ventured beyond her narrow room. Momma insists it's for Lilly's own protection, that people would be afraid if they saw her. But on this unforgettable night, Lilly is taken outside for the first time - and sold to the circus sideshow.

More than two decades later, nineteen-year-old Julia Blackwood has inherited her parents' estate and horse farm. For Julia, home was an unhappy place full of strict rules and forbidden rooms, and she hopes that returning might erase those painful memories. Instead, she becomes immersed in a mystery involving a hidden attic room and photos of circus scenes featuring a striking young girl.

At first, The Barlow Brothers' Circus is just another prison for Lilly. But in this rag-tag, sometimes brutal world, Lilly discovers strength, friendship, and a rare affinity for animals. Soon, thanks to elephants Pepper and JoJo and their handler, Cole, Lilly is no longer a sideshow spectacle but the circus's biggest attraction - until tragedy and cruelty collide.

It will fall to Julia to learn the truth about Lilly's fate and her family's shocking betrayal, and find a way to make Blackwood Manor into a place of healing at last. Moving between Julia and Lilly's stories, Ellen Marie Wiseman portrays two extraordinary, very different women in a novel that, while tender and heartbreaking, offers moments of joy and indomitable hope.

Release date: July 25, 2017

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Life She Was Given

Ellen Marie Wiseman

Daddy called this time of day twilight, and the outside looked painted in only two colors—green and blue. The row of pine trees on the other side of the barn, past the fields where the horses played, looked like the felt Lilly used for doll blankets. Shadows were everywhere, growing darker by the minute.

Lilly skimmed the edge of the woods, looking for the deer she saw yesterday. There was the crooked willow tree. There was the rock next to the bush that turned red in the winter. There was the broken log next to the stone fence. There was the—She stopped and swung the telescope back to the fence. Something looked different on the other side of the woods, near the train tracks that cut through the faraway meadow. She took the telescope away from her eye, blinked, then looked through it again and gasped. Air squeaked in her chest, like it always did when she got excited or upset.

A string of blue, red, yellow, and green lights—like the ones Daddy put above her bed at Christmastime—hung above a giant glowing house made out of something that looked like cloth. More lights surrounded other houses that looked like fat, little ghosts. Lilly couldn’t make out the words, but there were signs too, with letters lit up by colored bulbs. Flags hung from tall poles, and a line of square yellow lights floated above the railroad tracks. It looked like the windows of a stopped train. A really long one.

Lilly put down the telescope, waited for her lungs to stop whistling, then went over to her bookcase and pulled out her favorite picture book. She flipped through the pages until she found what she was looking for—a colorful drawing of a striped tent surrounded by wagons, horses, elephants, and clowns. She hurried back to the window to compare the shape of the tent in the book to the glowing house on the other side of the trees.

She was right.

It was a circus.

And she could see it.

Normally, the only things outside her window were horses and fields, and Daddy and his helper working on the white fences or yellow horse barn. Sometimes, Momma walked across the grass to the barn, her long blond hair trailing behind her like a veil. Other times, trucks pulled into the barn driveway and Daddy’s helper put horses in and out of trailers or unloaded bags and hay bales. Once, two men in baggy clothes—Daddy called them bums—walked up the driveway and Daddy’s helper came out of the barn with a shotgun. If Lilly was lucky, deer came out of the woods, or raccoons scurried along the fence toward the feed shed, or a train zoomed along the tracks. And if she put her ear to the window, the chug of the train’s engine or the shriek of the whistle came through the glass.

But now there was a circus outside her window. A real, live circus! For the first time in her life, she was seeing something different that wasn’t in a picture book. It made her happy, but a little bit mad at herself too. If she hadn’t been reading all afternoon, she might have seen the train stop to unload. She could have watched the tents go up and caught sight of the elephants and zebras and clowns. Now it was too dark to see anything but lights.

She put down the book and counted the boards around the window. Sometimes counting made her feel better. One, two, three, four, five. It didn’t help. She couldn’t stop thinking about what she’d missed. She pressed her ear against the glass. Maybe she could hear the ringleader’s cries or the circus music. The only thing she heard was air squeaking in her chest and her heartbeat going fast.

On the windowsill, her cat, Abby, woke up and blinked. Lilly wrapped an arm around the orange tabby and pulled her close, burying her nose in the animal’s soft fur. Abby was her best friend and the smartest cat in the world. She could stand on her hind legs to give kisses and lift her front paw to shake. She even jumped up on Lilly’s bed and got down when told.

“I bet Momma will go to the circus,” Lilly said. “She doesn’t have to worry about people being afraid of her.”

The cat purred.

What would it be like to see an elephant in person? Lilly wondered. What would it feel like to touch its wrinkly skin and look into its big brown eyes? What about riding a pink and white horse on a carousel? Or walking among other people, eating peanuts and cotton candy? What about watching a real, live lion perform?

As far back as Lilly could remember, there had been times at night after her light was out when she snuggled in her bed, her mind racing with thoughts of leaving her room and going downstairs. She’d read enough books to know there was more than one floor in a house, and she imagined sneaking across the attic, finding a staircase, making her way through the bottom floors of Blackwood Manor, and walking out the front door. She imagined standing with her feet on the earth, taking a deep breath, and for the first time in her life, smelling something besides old wood, cobwebs, and warm dust.

One of her favorite games during Daddy’s weekly visits was guessing the different smells on his clothes. Sometimes he smelled like horses and hay, sometimes shoe polish or smoke, sometimes baking bread or—what did he call that stuff that was supposed to be a mix of lemons and cedar trees? Cologne? Whatever it was, it smelled good.

Daddy had told her about the outside world and she had read about it in books, but she had no idea how grass felt between her toes, or how tree bark felt in her hand. She knew what flowers smelled like because Daddy brought her a bouquet every spring, but she wanted to walk through a field of dandelions and daisies, to feel dirt and dew on her bare feet. She wanted to hear birds singing and the sound of the wind. She wanted to feel a breeze and the sun on her skin. She’d read everything she could on plants and animals, and could name them all if given the chance. But besides Abby and the mice she saw running along the baseboard in the winter, she’d never seen a real animal up close.

Her other favorite game was picking a place in her book of maps and reading everything she could about it, then planning a trip while she fell asleep, deciding what she would do and see when she got there. Her favorite place was Africa, where she pictured herself running with the lions and elephants and giraffes. Sometimes she imagined breaking the dormer window, crawling out on the roof, climbing down the side of the house, and sneaking over to the barn to see the horses. Because from everything she had seen and read, they were her favorite animals. Besides cats, of course. Not only were horses strong and beautiful, but they pulled wagons and sleighs and plows. They let people ride on their backs and could find their way home if they got lost. Daddy said Blackwood Manor’s horses were too far away from the attic window to tell who was who, so Lilly made up her own names for them—Gypsy, Eagle, Cinnamon, Magic, Chester, Samantha, Molly, and Candy. How she would have loved to get close to them, to touch their manes and ride through the fields on their backs. If only it weren’t for those stupid swirly bars outside her window that Momma said were there for her own good. Then she remembered Momma’s warning, and as quickly as they started, her dreams turned to nightmares.

“The bars are there to protect you,” Momma said. “If someone got in, they’d be afraid of you and they’d try to hurt you.”

When Lilly asked why anyone would be afraid of her, Momma said it was because she was a monster, an abomination. Lilly didn’t know what an abomination was, but it sounded bad. Her shoulders dropped and she sighed in the stillness of her room. There would be no circus for her. Not now, not ever. There would be no getting out of the attic either. The only way she would see the world was through her books. Daddy said the outside world was not as wonderful as she thought, and Lilly should be happy she had a warm bed and food to eat. A lot of people didn’t have a house or a job, and they had to stand in line for bread and soup. He told her a story about banks and money and some kind of crash, but she didn’t understand it. And it didn’t make her feel better anyway.

She gathered Abby in her arms and sat on her iron bed tucked beneath a wallpapered nook with a rounded ceiling. Her bedside lamp cast long shadows across the plank floor, meaning it would be dark soon and it was time to turn off the light. She didn’t want to forget again and have Momma teach her another lesson. Momma had warned her a hundred times if anyone saw her light and found her up there they would take her away and she’d never see her or Daddy or Abby again. But one night last week, Lilly started a new book and forgot.

She put the cat on the bed and examined the scars on her fingers. Daddy was right, the lotion made them feel better. But oh, how the flame of Momma’s lantern had burned!

“Spare the rod and spoil the child,” Momma said.

Lilly wanted to ask if the Bible said anything about sparing the fire, but didn’t dare. She was supposed to know what the Bible said.

“I wonder what Momma would do if she found out I read the books from Daddy instead of that boring old Bible?” she asked Abby. The cat rubbed its face on Lilly’s arm, then curled into a ball and went back to sleep.

Lilly took the Bible from the nightstand—she didn’t dare put it anywhere else—moved the bookmark in a few pages, and set it back down. Momma would check to see how much reading she had done this week and if the bookmark hadn’t moved, Lilly would be in big trouble. According to Momma, the Holy Bible and the crucifix on the wall above her bed were the only things she needed to live a happy life.

Everything else in the room came from Daddy—the wicker table set up for a tea party, complete with a lace doily, silver serving tray, and china cups. The matching rocking chair and the teddy bear sitting on the blue padded stool next to her wardrobe. The dollhouse filled with miniature furniture and straight-backed dolls. The model farm animals lined up on a shelf above her bookcase, all facing the same way, as if about to break into song. Three porcelain dolls with lace dresses in a wicker baby pram, one with eyes that opened and closed. And, of course, her bookcase full of books. It seemed, for a while, like Daddy would give her everything—until she read Snow White and asked for a mirror.

Sometimes, in the middle of the night, when she was certain everyone was asleep and there was nothing but blackness outside her window, she turned on her light and studied her reflection in the glass. All she saw was a blurry, ghost-like mask looking back at her, the swirly metal outside coiling across her skin like snakes. She stared at her white reflection and touched her forehead and nose and cheeks, trying to find a growth or a missing part, but nothing stuck out or caved in. When she asked Daddy what was wrong with her, he said she was beautiful to him and that was all that mattered. But his eyes looked funny when he said it, and she didn’t think he was telling the truth. He’d be in big trouble if Momma found out because Momma said lying was a sin.

Good thing Lilly would never tell on Daddy. He was the one who taught her how to read and write, and how to add and subtract numbers. He was the one who decorated the walls of her room with rose-covered wallpaper and brought her new dresses and shoes when she got too big for the old ones. He was the one who brought Abby food and let Lilly in the other part of the attic so she could walk and stretch. One time, he even brought up a wind-up record player and tried to teach her the Charleston and tango, but she got too tired and they had to stop. She loved the music and begged him to leave the record player in her room. But he took it back downstairs because Momma would be mad if she found it.

Momma brought food and necessities, not presents. She came into Lilly’s room every morning—except for the times she forgot—with a tray of toast, milk, eggs, sandwiches, apples, and cookies, to be eaten over the rest of the day. She brought Lilly soap and clean towels, and reminded her to pray before every meal. She stood by the door every night with a ring of keys in her hands and waited for Lilly to kneel by her bed to ask the Lord to forgive her sins, and to thank Him for giving her a mother who took such good care of her. Other than that, Momma never came in her room just to talk or have fun. She never said “I love you” like Daddy did. Lilly would never forget her seventh birthday, when her parents argued outside her door.

“You’re spoiling her with all those presents,” Momma said. “It’s sinful how much you give her.”

“It’s not hurting anyone,” Daddy said.

“Nevertheless, we need to stop spending money.”

“Books aren’t that expensive.”

“Maybe not, but what if she starts asking questions? What if she wants to come downstairs or go outside? Are you going to say no?”

At first, Daddy didn’t say anything and Lilly’s heart lifted. Maybe he would take her outside after all. Then he cleared his throat and said, “What else is she supposed to do in there? The least we can do is try to give her a normal birthday. It’s not her fault she—”

Momma gasped. “It’s not her fault? Then whose is it? Mine?”

“That’s not what I was going to say,” Daddy said. “It’s not anyone’s fault. Sometimes these things just happen.”

“Well, if you had listened to me from the beginning, we wouldn’t. . .” She made a funny noise, like her words got stuck in her throat.

“She’s still our daughter, Cora. Other than that one thing, she’s perfectly normal.”

“There’s nothing normal about what’s on the other side of that door,” Momma said, her voice cracking.

“That’s not true,” Daddy said. “I talked to Dr. Hillman and he said—”

“Oh, dear Lord . . . tell me you didn’t! How could you betray me like that?” Momma was crying now.

“There, there, my darling. I didn’t tell anyone. I was just asking Dr. Hillman if he had ever seen . . .”

Momma’s sobs drowned out his words and her footsteps hurried across the attic.

“Darling, wait!” Daddy said.

The next day, Lilly quit praying before every meal, but she had not told Momma that. Since then, she had disobeyed her mother in a hundred little ways. Momma said it was wicked to look at her naked body and made Lilly close her eyes during her weekly sponge bath until she was old enough to wash herself. Now Lilly looked down at her milk-colored arms and legs when she bathed, examining her thin white torso and pink nipples. She felt ashamed afterward, but she wasn’t being bad on purpose. She just wanted to know what made her a monster. The only thing she knew for sure was that her parents looked different than she did. Momma had curly blond hair and rosy skin; Daddy had a black mustache, black hair, and tan skin; but her skin was powder-white, her long, straight hair the color and texture of spider webs. It was like God forgot to give her a color. Is that what made her a monster? Or was it something else?

Now, hoping she’d be able to see more of the circus tomorrow, she changed into her nightclothes, climbed into bed, and switched off the light. Then she realized Momma hadn’t come up to make sure she said her prayers.

Lilly curled up next to Abby and pulled her close. “She’s probably at the circus,” she said, closing her eyes.

The next night, after Lilly first saw the circus outside her window, the rattle of a key in her door startled her awake. She sat up and reached for her bedside lamp, then stopped, her fingers on the switch. It was the middle of the night and if Momma saw the light, it would mean big trouble. Maybe Momma had found out she’d spent the entire day watching the circus through her telescope instead of straightening her room and reading the Bible. The circus looked tiny through the end of her telescope and she couldn’t make out every detail, but no matter what Momma did to her, it was worth seeing the elephants and giraffes being taken into the big top. It was worth seeing the crowds of people outside the tents and the parade of wagons and clowns and costumed performers. It had been the most exciting day of her life, and nothing was going to ruin it. She took her hand away from the lamp and, one at a time, touched her fingers with her thumbs. One, two, three, four. The door opened and Momma slipped inside carrying an oil lantern. Lilly watched her enter and her belly trembled. Momma never came into her room this late. At the end of the bed, Abby lifted her furry head, surprised to see Momma too.

Momma—Daddy said her real name was Coralline—was a tall, pretty woman, and she always wore her long blond hair pinned back on the sides. Her only jewelry was the wedding band on her left hand, and she dressed in simple skirts and sensible shoes in the name of modesty and for the glory of God. Daddy said Momma put on her best dresses and furs when she went out to important dinners and parties, but only because that was what everyone in the outside world expected. Lilly didn’t understand why Momma changed what she looked like, but Daddy said that was okay. One time, Daddy showed her a picture of Momma all dressed up and Lilly thought it was someone else.

Daddy liked to tell the story of how he had first spotted Momma between the barn and the round pen, sitting on a barrel watching the horses play in the field. Momma’s father, a retired Pentecostal minister who always dreamed of raising horses, had come to Blackwood Manor Horse farm to buy a stallion. Daddy thought Momma was the prettiest girl he had ever seen. But it was six months before she would talk to him, and another six before she agreed to have dinner. For some reason, Momma’s parents didn’t trust Daddy. But eventually Momma and Daddy were walking hand in hand through the apple orchards; then they got married. When Daddy got to that part of the story, his face always changed to sad and he said Momma had a hard time growing up.

Now, Momma came into Lilly’s room in a flowery dress and pink heels. Her lips were painted red and she was wearing a yellow hat. Lilly couldn’t stop staring. She had never seen Momma dressed like that, not in person anyway. Momma’s cheeks were flushed and she was breathing hard, as if she had run up the stairs.

Lilly’s stomach turned over. Daddy was supposed to come back from Pennsylvania tomorrow. He promised birthday presents first thing. But he had told her a long time ago that she didn’t need to worry about being left alone when he and Momma went out because his helper was always downstairs in case someone called about a horse. If “something” happened to Daddy and Momma, the helper would read a letter in Daddy’s desk. He would find Lilly in the attic, and he would know what to do. Lilly wasn’t sure what “something” was, but she knew it was bad. What if Momma was here to tell her “something” had happened to Daddy and he wasn’t coming back?

Lilly touched her tongue to each tooth and counted, waiting for Momma to speak. One, two, three, four . . .

Then Momma smiled.

Momma never smiled.

“I’ve got a surprise for you,” Momma said.

Lilly blinked. She didn’t know what to say. Daddy brought surprises, not Momma. “Where’s Daddy?” she managed.

“Get dressed,” Momma said. “And hurry up, we don’t have much time.”

Lilly pushed back her covers and got out of bed. Abby sat up and stretched her front legs, treading the blanket with her claws. “Is someone coming to see me?” Lilly asked Momma.

Besides her parents, no one had ever been inside her room. One winter she got sick and Daddy wanted to call a doctor, but Momma refused because the doctor would take her away and put her “some place.” Instead Daddy spent three days wiping Lilly’s forehead and applying mustard powder and warm dressings to her chest. She would never forget the sad look on his face when she woke up and said, “Daddy? What’s ‘some place’?”

“It’s a hospital for sick people,” Daddy said. “But don’t worry, you’re staying right here with us.”

Now, Momma watched Lilly take her dress from the back of the rocking chair. Lilly’s legs felt wobbly. What if someone was coming to take her “some place”?

Momma chuckled. “No, Lilly, no one is coming to see you.”

Lilly glanced at Momma, her stomach getting wobbly too. Momma never laughed. Maybe she had been drinking the strange liquid Daddy sometimes brought up to her room in a silver container. Lilly didn’t know what the drink was, but it made his eyes glassy and gave his breath a funny smell. Sometimes it made him laugh more than usual. What did he call it? Whiskey? No, that was impossible. Momma would never drink whiskey. Drinking alcohol was a sin.

“Why do I have to get dressed, Momma?”

“Because today’s your birthday, remember?”

Lilly frowned. Momma didn’t care about birthdays. “Yes,” she managed.

“And I’m sure you saw the circus outside.”

Lilly nodded.

“Well, that’s where we’re going.”

Lilly stared at Momma, her mouth open. Her legs shook harder, and her arms too. “But . . . what . . . what if someone sees me?”

Momma smiled again. “Don’t worry, circus performers are used to seeing people like you. And no one else will be there but us. Because against my better judgment, your father insisted on paying the circus owner to put on a special show for you.”

Goose bumps popped up on Lilly’s arms. Something felt bad, but she didn’t know what. She glanced at Abby, as if the cat would know the answer. Abby looked back at her with curious eyes. “Daddy said he wasn’t coming back until tomorrow,” Lilly said.

Momma kept smiling, but her eyes changed. The top half of her face looked like it did when Lilly was in big trouble. The bottom half looked like someone Lilly had never seen before. “He came home early,” Momma said.

“Then where is he?” Lilly said. “He always comes to see me first when he gets home.”

“He’s waiting for us over at the circus. Now hurry up!”

“Why didn’t he come get me instead of you?” As soon as the words were out of her mouth, Lilly wished she hadn’t said them.

Momma walked toward her and her hand rose with a sudden speed. It struck Lilly across the jaw and she fell to the floor. Abby leapt sideways on the bed and crouched next to the wall, her ears back.

“You ungrateful spawn of the devil!” Momma yelled. “How many times have I told you not to question me?”

“I’m sorry, Momma,” Lilly cried.

Momma thumped her with the side of her foot. “What did I do to deserve this curse?” she hissed. “Now get on your knees and pray.”

“But, Momma . . .” Lilly’s sobs were too strong. She couldn’t get up and she could barely breathe. She crawled to her bed with her hair hanging in her face and pulled herself up, air squeaking in her chest.

“Bow your head and ask for forgiveness,” Momma said.

Lilly put her hands together beneath her chin and counted her fingers by pressing them against each other. One, two, three, four. “Oh Lord,” she said, pushing the words out between wheezes. Five, six, seven, eight. “Please forgive me for questioning my momma, and for all the other ways I have made her life so difficult.” Nine, ten. “I promise to walk the straight and narrow from here on out. Amen.”

“Now get dressed,” Momma said. “We don’t have much time.”

Lilly got off her knees and put on her undergarments with shaky hands, then took off her nightgown and pulled her play dress on over her head. Her side hurt where Momma kicked her and snot ran from her nose.

“Not that one,” Momma said. “Find something better.”

Lilly took off the play dress and half-walked, half-stumbled over to the wardrobe. She pulled out her favorite outfit, a yellow satin dress with a lace collar and ruffled sleeves. “Is this one all right?” she said, holding up the dress.

“That will do. Find your best shoes too. And brush your hair.”

Lilly put on the dress and tied the belt behind her back. She brushed her hair—one, two, three, four, five, six strokes—then sat on the bed to put on her patent leather shoes. Abby edged across the covers and rubbed against Lilly’s arm. Lilly gave her a quick pet, then got up and stood in the middle of the room, her ribs aching and her heart thumping. Momma opened the door and stood back, waiting for Lilly to go through it.

Lilly had waited for this moment her entire life. But now, more than anything, she wanted to stay in the attic. She didn’t want to go outside. She didn’t want to go to the circus. Her chest grew tighter and tighter. She could barely breathe.

“Let’s go,” Momma said, her voice hard. “We don’t have all night.”

Lilly wrapped her arms around herself and started toward the door, gulping air into her lungs. Then she stopped and looked back at Abby, who was watching from the foot of her bed.

“That cat will be here when you get back,” Momma said. “Now move it.”

Eighteen-year-old Julia Blackwood glanced up and down the supermarket aisle to make sure no one was watching. The store was small, maybe thirty feet wide by forty feet long, and she could see over the shelves and into each corner. A pimple-faced teenager sat on a stool behind the counter, chewing gum and staring at a black and white television above the cash register. A radio on a shelf played “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” while a gray-haired lady checked eggs for cracks next to the open dairy cooler door.

Julia took a deep breath, went down on one knee, and pretended to tie her grease-spotted Keds. She glanced both ways down the aisle to make sure no one was watching, grabbed a can of Spam off the middle shelf, slipped it into her coat pocket, then straightened and pushed her hair behind her ears. The boy at the counter absently picked at a pimple on his chin, his eyes still glued to the television. Julia let out her breath and made her way to the next aisle, walking slowly and pretending to examine the groceries. She plucked a small apple from a produce bin, put it in her pocket, and made her way toward the counter.

“Can I get the key to the restroom?” she asked the pimple-faced boy.

Still watching television, the boy reached beneath the cash register and handed her a key on a brown rabbit foot. Then he snapped his gum and grinned at her. “Just replaced the soap this morning.”

Heat rose in Julia’s cheeks and she had to fight the urge to leave. The boy knew why she wanted to use the bathroom. It was the fourth time in as many months that there was no water in her room above the liquor store—this time due to frozen pipes instead of an unpaid bill—and she hadn’t washed her hair or taken a shower in three days. Sure, no one at work would know whether or not she’d had a bath, but who wanted an oily-haired waitress serving them fried eggs and onion-covered burgers? Big Al’s Diner was already a greasy spoon; it didn’t need any more help in that department. Instead of leaving, she swallowed her pride, took the key from the boy, and trudged to the back of the store.

The cold, green-enameled restroom smelled like rotten food and old socks. Grime and black mold colored the grout between the broken, mismatched floor tiles, and a jagged yellow crack ran across the toilet seat. Julia washed her hands in the silver-legged sink, dried them with brown paper towels, then ate the apple as fast as she could, trying to ignore the stench of old urine. When she was finished, she stripped down to her underwear and bra, folded her cranberry-colored waitress uniform on top of her coat, and put them on the toilet tank lid—the only place that looked halfway clean. Shivering, she scrubbed her face and armpits with paper towels and Lava soap, then washed her hair in the sink, trying not to get soaked. The water was ice cold and the gritty lather made her hair feel like straw, but at least it would be clean. When the last of the soap was out of her hair, she used paper towels to squeeze out the excess water, then got dressed again, combed the tangles out of her hair, put it in a bun, and studied her reflection in the tarnished mirror.

The stealthy progress of time since she ran away from home three years ago showed in her pronounced cheekbones and the rings under her eyes. Her tanned, smooth skin had turned pale and chalky from too little sleep and

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...