- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

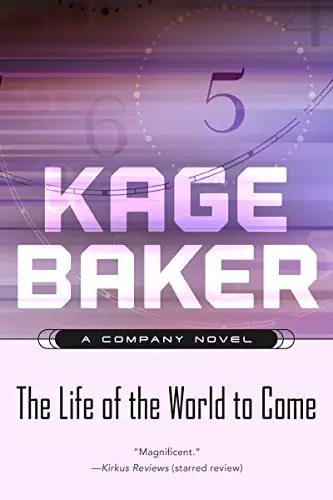

From idea to flesh to myth, this is the story of Alec Checkerfield: Seventh Earl of Finsbury, pirate, renegade, hero, anomaly, Mendoza's once and future love.

Mendoza is a Preserver, which means that she's sent back from the twenty-fourth century by Dr. Zeus, Incorporated - the Company - to recover things from the past which would otherwise be lost. She's a botanist, a good one. She's an immortal, indestructible cyborg. And she's a woman in love.

In sixteenth century England, Mendoza fell for a native, a renegade, a tall, dark, not handsome man who radiated determination and sexuality. He died a martyr's death, burned at the stake. In nineteenth century America, Mendoza fell for an eerily identical native, a renegade, a tall, dark, not handsome man who radiated determination and sexuality. When he died, she killed six men to avenge him.

The Company didn't like that - bad for business. But she's immortal and indestructible, so they couldn't hurt her. Instead, they dumped her in the Back Way Back.

Meanwhile, back in the future, three eccentric geniuses sit in a parlor at Oxford University and play at being the new Inklings, the heirs of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. Working for Dr. Zeus, they create heroic stories and give them flesh, myths in blood and DNA to protect the future from the World to Come, the fearsome Silence that will fall on the world in 2355. They create a hero, a tall, dark, not handsome man who radiates determination and sexuality.

"Now," stranded 150,000 years in the past, there are no natives for Mendoza to fall in love with. She tends a garden of maize, and she pines for the man she lost, twice. For Three. Thousand. Years.

Then, one day, out of the sky and out of the future comes a renegade, a timefaring pirate, a tall, dark, not handsome man who radiates determination and sexuality. This is the beginning of the end.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: November 1, 2005

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Life of the World to Come

Kage Baker

150,000 BCE (more or less)

Rain comes on the west wind, ice out of the blue north. The east wind brings hazes, smokes, the exhalation of the desert on the distant mainland; and hot winds come out of the south, across the wide ocean.

The corn and tomatoes like the west wind. The tall corn gleams wet like cellophane, the tomato leaves pearl and bow down. The onions and garlic, on the other hand, get sullen and shreddy and threaten mold in the rain. Poor old cyborg with a few screws missing—me—sits watching them in fascination.

When I find myself giving my vegetables personalities, it's a sign I've been sitting here watching the rain too long. Or the bright ice. Or the hazes or the hot thin stripes of cloud. Accordingly then, I put on a coat or hat, depending on which way the wind is blowing, and walk out to have a look at the world.

What I have of the world. When I rise, I can walk down the canyon to my brief stony beach to see if anything interesting has washed up there. Nothing ever has. Out on the rocks live sea lions, and they groan and howl so like old men that a mortal would be deceived. I ignore them.

Or I can walk up the canyon and climb high narrow hills, through the ferny trees, until I stand on rimrock in the wind. I can look along the spine of my island in every direction. Ocean all around, the horizon vanishing in cloud. No ships ever, of course—hominids haven't yet progressed beyond clinging to floating logs, when they venture to sea at all.

And I begin my day. Much to do: the planting or the harvest, all the greenhouse work, the tasks of replacing irrigation pipes and cleaning out trenches. A little work on projects of my own, maybe planing wood to replace such of my furniture as has fallen apart with age. I take a meal, if I remember to. I wander back down to the beach in the evening, to watch the little waves run up on the shore, and sometimes I forget to go home.

One day a small resort town will be built on this stony beach, palm trees and yellow sand brought in on barges, to make a place as artificial as I am. The water will be full of excursion boats, painted bright. Out there where that big rock is, the one that looks like a sugarloaf, a great ballroom will stand. I would dearly love to go dancing there, if he were with me.

Sometimes I torment myself by walking along and imagining the crescent of street lined with shops and cafés, gracious hotels. I can almost see the mortal children with their ice cream. I can almost hear the music. I sit down where there will be a terrace someday, complete with little tables and striped umbrellas. Sometimes a waiter has materialized at my elbow, white napkin over his arm, deferentially leaning from the waist to offer me a cocktail. He's never really there, of course, nor will he ever be.

But the other man will be here, the one I see only in my dreams, or behind my eyes as I watch the quiet water in the long hours. I have waited for him, alone on this island, for three thousand years. I think.

I'm not certain, though, and this is the reason I have bound more paper into my book, vandalized another label printer cartridge, cut myself another pen: it may be that if I write things down I can keep track of the days. They have begun to float loose in an alarming way, like calendar leaves fluttering off the wall.

I walked out this morning in the full expectation of thinning my tomato seedlings and—imagine my stupefaction! Row upon row of big well-grown plants stretched away as far as the eye could see, heavy with scarlet fruit. Well-watered, weeded, cared for by someone. Me? I swear I can't recall, nor does my internal chronometer record any unusual forward movement; but something, my world or me, is slipping out of time's proper flow.

What does it mean, such strangeness? Some slow deterioration of consciousness? Supposedly impossible in a perfectly designed immortal. But then, I'm not quite mechanically sound, am I? I'm a Crome generator, one of those aberrant creatures the mortals call psychic, or second-sighted . I'm the only one on whom the Company ever conferred immortality, and I'll bet they're sorry now.

Not that they meant to do it, of course. Somebody made a mistake when I was being evaluated for the honor of eternal service, didn't catch the latent flaw, and here I am like a stain in permanent ink. No way to erase me. Though marooning me at this station has undoubtedly solved a few problems for them.

Yet my prison is actually a very nice place, quite the sort of spot I'd choose to live, if I'd ever had a choice: utterly isolated, beautifully green, silent in all its valleys and looming mountains, even the sea hushed where it breaks and jumps up white on the windward cliffs.

Only one time was there ever noise, terrible sounds that echoed off the mountains. I hid indoors all that day, paced with my hands over my ears, hummed to myself to shut out the tumult. At least it was over in a few hours. I have never yet ventured back over into Silver Canyon to see if the little people there are all dead. I knew what would happen to them when I sent that signal, alerting Dr. Zeus to their presence. Were they refugees from Company persecution? Did I betray them? Well—more blood on my soul. I was only following orders, of course.

(Which is another reason I don't mind being an old field slave here, you see. Where else should I be? I've been responsible for the deaths of seven mortal men and unknown numbers of whatever those little pale things were.)

What the eyes can't see, the heart doesn't grieve over, isn't that what they say? And no eyes can see me here, that's for sure, if I generate the blue radiation that accompanies a fit of visions, or do some other scary and supposedly impossible thing like move through time spontaneously. I am far too dangerous to be allowed to run around loose, I know. Am I actually a defective? Will my fabulous cyborg super-intelligence begin to wane? It might be rather nice, creeping oblivion. Perhaps even death will become possible. But the Company has opted to hide me rather than study me, so there's no way to tell.

I have done well, for a cast-off broken tool. Arriving, I crawled from my transport box with just about nothing but the prison uniform I wore. Now I have a comfortable if somewhat amateurish house I built myself, over long years, with a kitchen of which I am particularly proud. The fireplace draws nicely, and the little sink is supplied by a hand pump drawing on the well I drilled. I have a tin tub in my back garden, in which I bathe. Filled before midday heat rises, the water is reasonably warm by nightfall, and serves to water the lawn afterward. So very tidy, this life I've built.

Do I lack for food and drink? No indeed. I grow nearly everything I consume. About all I receive from the Company anymore are its shipments of Proteus brand synthetic protein.

(Lately the Proteus only seems to come in the assortment packs, four flavors: Breakfast Bounty, Delicate and Savory, Hearty Fare, and Marina. The first two resemble pork and/or chicken or veal, and are comparatively inoffensive. I quite like Hearty Fare. It makes the best damned tamale filling I've ever found. Marina, on the other hand, is an unfortunate attempt to simulate seafood. It goes straight into my compost heap, where it most alarmingly fails to decompose. There has been no response to my requests for a change, but this is a prison, after all.)

Have I written that before, about the Proteus? I have a profound sense of déjà vu reading it over, and paused just now to thumb back through the book to see if I was duplicating a previous entry. No. Nothing in the first part, about England, and nothing in the afterword I wrote on my trial transcript. More of this slipping time business. Nothing has again been so bad as that day I paused in weeding to wipe my sweating face and looked up to see the row just cleared full of weeds again, and the corn a full foot taller than it had been a moment before. But nothing else out of whack! No sign of dust or cobwebs in my house, no conflicting chronometers.

Yes, I really must try to anchor myself here and now. It may be a bit late for mental health, but at least I might keep from sinking into the rock of this island, buried under centuries, preserved like a fossil in a strata of unopened Proteus Marina packets. I suppose it wouldn't have come to this pass if I'd seen another living soul in three thousand years who wasn't a dream or a hallucination.

If only he'd come for me.

I don't know if I should write about him. The last time I did that I was depressed for years, roamed this island in restless misery end to end. Not a good thing to summon up a ghost when you're all alone, especially when you'd sell your soul—if you had one—to join him in his long grave. But then, perhaps misery is what's needed to fasten me securely to the world. Perhaps this curiously painless existence is the problem.

If I look across the table I can see him standing there, as I saw him first in England in 1554: a tall mortal in the black robe of a scholar, staring at me in cold and arrogant dislike. We weren't enemies long. I was very young and so fascinated by the mortal's voice, and his fine big hands … I wake at night sometimes, convinced I can feel his mortal flesh at my side, hot as the fire in which he was martyred.

So I look away: but there he is in the doorway, just as he stood in the doorway of the stagecoach inn in the Cahuenga Pass, when he walked back into my life in 1863. He was smiling then, a Victorian gentleman in a tall hat, smooth and subtle to conceal his deadly business. If he'd succeeded in what he'd been sent from England to do, the history of nations would have been drastically different. I was only an incidental encounter that time, entering late at the last act in his life; but I held him as he lay dying, and I avenged his death.

Barbaric phrase, avenged his death. I was educated to be above such mortal nonsense, yet what I did was more than barbaric. I don't remember tearing six American Pinkerton agents limb from limb, but it appears I did just that, after they'd emptied their guns into my lover.

But when he lay there with blood all over his once-immaculate clothes, my poor secret agent man, he agreed to come back for me. He knew something I didn't, and if he'd lived for even thirty more seconds he might have let me in on the secret.

I really should ponder the mystery, but now that I've summoned my ghost again all I can think of is the lost grace of his body. I should have let well enough alone. The dreams will probably begin again now. I am impaled on his memory like an insect on a pin. Or some other metaphor …

I've spent the last few days damning myself for an idiot, when I haven't been crying uncontrollably. I am so tired of being a tragic teenager in love, especially after having been one for over thirty centuries. I think I'll damn someone else for a change.

How about Dr. Zeus Incorporated, who made me the thing I am? Here's the history: the Company began as a cabal of adventurers and investors who found somebody else's highly advanced technology. They stole it, used it to develop yet more advanced technology (keeping all this a secret from the public, of course), and became very very wealthy.

Of course, once they had all the money they needed, they must have more; so they developed a way to travel into the past and loot lost riches, and came up with dodgy ways to convey them into the future, to be sold at fabulous profits.

Along the way, they developed a process for human immortality.

The only problem with it was, once they'd taken a human child and put it through the painful years of transformation, what emerged at the end wasn't a human adult but a cyborg, an inconveniently deathless thing most mortals wouldn't want to dine at one table with. But that's all right: cyborgs make a useful workforce to loot the past. And how can we rebel against our service, or even complain? After all, Dr. Zeus saved us from death.

I myself was dying in the dungeons of the Spanish Inquisition when I was rescued by a fast-talking operative named Joseph, damn his immortal soul. Well, little girl, what'll it be? Stay here and be burned to death, or come work for a kindly doctor who'll give you eternal life? Of course, if you'd rather die …

I was four years old.

The joke is, of course, that at this precise moment in time none of it's even happened yet. This station exists in 150,000 BCE, millennia before Joseph's even born, to say nothing of everyone else I ever knew, including me.

Paradox? If you view time as a linear flow, certainly. Not, however, if you finally pay attention to the ancients and regard time (not eternity) as a serpent biting its own tail, or perhaps a spiral. Wherever you are, the surface on which you stand appears to be flat, to stretch away straight behind you and before you. As I understand temporal physics, in reality it curves around on itself, like the coiled mainspring in a clock's heart. You can cross from one point of the coil to another rather than plod endlessly forward, if you know how. I was sent straight here from 1863. If I were ever reprieved I could resume life in 1863 just where I left it, three thousand years older than the day I departed.

Could I go forward beyond that, skip ahead to 1963 or 2063? We were always told that was impossible; but here again the Company has been caught out in a lie. I did go forward, on one memorable occasion. I got a lungful of foul air and a brief look at the future I'd been promised all my immortal life. It wasn't a pleasant place at all.

Either Dr. Zeus doesn't know how to go forward in time, or knows how and has kept the information from its immortal slaves, lest we learn the truth about the wonderful world of the twenty-fourth century. Even if I were to tell the others what I know, though, I doubt there'd be any grand rebellion. What point is there to our immortal lives but the work?

Undeniably the best work in the world to be doing, too, rescuing things from destruction. Lost works by lost masters, paintings and films and statues that no longer exist (except that they secretly do, secured away in some Company warehouse). Hours before the fires start, the bombs fall, doomed libraries swarm with immortal operatives, emptying them like ants looting a sugar bowl. Living things saved from extinction by Dr. Zeus's immortals, on hand to collect them for its ark. I myself have saved rare plants, the only known source of cures for mortal diseases.

More impressive still: somewhere there are massive freezer banks, row upon row of silver tubes containing DNA from races of men that no longer walk the earth, sperm and ova and frozen embryos, posterity on ice to save a dwindling gene pool.

Beside such work, does it really matter if there is mounting evidence, as we plod on toward the twenty-fourth century, that our masters have some plan to deny us our share of what we've gathered for them up there?

I wear, above the Company logo on all my clothing, an emblem: a clock face without hands. I've heard about this symbol, in dark whispers, all my life. When I was sent to this station I was informed it's the badge of my penal servitude, but the rumor among immortals has always been that it's the sign we'll all be forced to wear when we do finally reach the future, so our mortal masters can tell us from actual persons. Or worse …

I was exiled to this hole in the past for a crime, but there are others of us who have disappeared without a trace, innocent of anything worse than complaining too loudly. Have they been shuffled out of the deck of time as I have been, like a card thrown under the table? It seems likely. Sentenced to eternal hard labor, denied any future to release them.

What little contact we've had with the mortals who actually live in the future doesn't inspire confidence, either: unappreciative of the treasures we bring them, afraid to venture from their rooms, unable to comprehend the art or literature of their ancestors. Rapaciously collecting Shakespeare's first folios but never opening them, because his plays are full of objectionable material and nobody can read anymore anyway. Locking Mozart sonatas in cabinets and never playing them, because Mozart had disgusting habits: he ate meat and drank alcohol. These same puritans are able, mind you, to order the massacre of those little pale people to loot their inventions.

But what's condemnation from the likes of me, killer cyborg drudging along here in the Company's fields, growing occasional lettuce for rich fools who want to stay at a fine resort when they time-travel? The Silence is coming for us all, one day, the unknown nemesis, and perhaps that will be justice enough. If only he comes for me before it does.

He'll come again! He will. He'll break my chains. Once he stood bound to a stake and shouted for me to join him there, that the gate to paradise was standing open for us, that he wouldn't rest until I followed him. I didn't go; and he didn't rest, but found his way back to me against all reason three centuries later.

He very nearly succeeded that time, for by then I'd have followed him into any fire God ever lit. History intervened, though, and swatted us like a couple of insects. He went somewhere and I descended into this gentle hell, this other Eden that will one day bear the name of Avalon. He won't let me rest here, though. His will is too strong.

Speak of the fall of Rome and it occurs!

Or the fall of Dr. Zeus, for that matter.

He has come again.

And gone again, but alive this time! No more than a day and a night were given us, but he did not die!

I still can't quite believe this.

He's shown me a future that isn't nearly as dark as the one I glimpsed. There is a point to all this, there is a reason to keep going, there is even—unbelievably—the remote possibility that … no, I'm not even going to think about that. I won't look at that tiny bright window, so far up and far off, especially from the grave I've dug myself.

But what if we have broken the pattern at last?

Must put this into some kind of perspective. Oh, I could live with seeing him once every three thousand years, if all our trysts went as sweetly as this one did. And it started so violently, too.

Not that there was any forewarning that it would, mind you. Dull morning spent in peaceful labor in the greenhouse, tending my latest attempt at Mays mendozaii. Sweaty two hours oiling the rollers on the shipping platform. Had set out for the high lake to dig some clay for firing when there came the roar of a time shuttle emerging from its transcendence field.

It's something I hear fairly frequently, but only as a distant boom, a sound wave weak with traveling miles across the channel from Santa Cruz Island, where the Company's Day Six resort is located. However, this time the blast erupted practically over my head.

I threw myself flat and rolled, looking up. There was a point of silver screaming away from me, coming down fast, leveling out above the channel, heading off toward the mainland. I got to my feet and stared, frowning, at its spiraled flight. This thing was out of control, surely! There was a faint golden puff as its gas vented and abruptly the shuttle had turned on its path, was coming back toward the station.

I tensed, watching its trajectory, ready to run. Oh, dear, I thought, there were perhaps going to be dead twenty-fourth-century millionaires cluttering up my fields soon. I'd have a lot of nasty work to do with body bags before the Company sent in a disaster team. Did I even have any body bags? Why would I have body bags? But there, the pilot seemed to have regained a certain amount of control. His shuttle wasn't spinning anymore and its speed was decreasing measurably, though he was still coming in on a course that would take him straight up Avalon Canyon. Oh, no; he was trying to land, swooping in low and cutting a swath through my fields. I cursed and ran down into the canyon, watching helplessly the ruination of my summer corn.

There, at last the damned thing was skidding to a halt. Nobody was going to die, but there were doubtless several very frightened Future Kids puking their guts up inside that shuttle just now. I paused, grinning to myself. Did I really have to deal with this problem? Should I, in fact? Wasn't my very existence here a Company secret? Oughtn't I simply to stroll off in a discreet kind of way and let the luckless cyborg pilot deal with his terrified mortal passengers?

But I began to run again anyway, sprinting toward the shuttle that was still sizzling with the charge of its journey.

I circled it cautiously, scanning, and was astounded to note that there were no passengers on board. Stranger still, the lone pilot seemed to be a mortal man; and that, of course, was impossible. Only cyborgs can fly these things.

But then, he hadn't been doing all that expert a job, had he?

So I came slowly around the nose of the shuttle, and it was exactly like that moment in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy, in black and white, moves so warily toward the door and looks across the threshold: then grainy reality shifts into Technicolor and she steps through, into that hushed and shocked moment full of cellophane flowers and the absolute unexpected.

I looked through the window of the shuttle and saw a mortal man slumped forward in his seat restraints, staring vacantly out at me.

Him, of course. Who else would it be?

Tall as few mortals are, and such an interesting face: high, wide cheekbones flushed with good color, long broken nose, deep-set eyes with colorless lashes. Fair hair lank, pushed back from his forehead. Big rangy body clad in some sort of one-piece suit of black stuff, armored or sewn all over with overlapping scales of a gunmetal color. Around his neck he wore a collar of twisted golden metal, like a Celtic torque. The heroic effect was spoiled somewhat by the nosebleed he was presently having. He didn't seem to be noticing it, though. His color was draining away.

Oh, dear. He was suffering from transcendence shock. Must do something about that immediately.

The strangest calm had seized me, sure sign, I fear, that I really have gone a bit mad in this isolation. No cries from me of "My love! You have returned to me at last!" or anything like that. I scanned him in a businesslike manner, realized that he was unconscious, and leaned forward to tap on the window to wake him up. Useless my trying to break out the window to pull him through. Shuttle windows don't break, ever.

After a moment or two of this he turned his head to look blankly at me. No sign of recognition, of course. Goodness, I had no idea whence or from when he'd come, had I? He might not even be English in this incarnation. I pulled a crate marker from my pocket and wrote on my hand DO YOU SPEAK CINEMA STANDARD? and held it up in his line of sight.

His eyes flickered over the words. His brow wrinkled in confusion. I leaned close to the glass and shouted:

"You appear to require medical assistance! Do you need help getting out of there?"

That seemed to get through to him. He moved his head in an uncertain nod and fumbled with his seat restraints. The shuttle hatch popped open. He stood up, struck his head on the cabin ceiling and fell forward through the hatchway.

I was there to catch him. He collapsed on me, I took the full weight of his body, felt the heat of his blood on my face. His sweat had a scent like fields in summer.

He found his legs and pulled himself upright, looking down at me groggily. His eyes widened as he realized he'd bled all over me.

"Oh. Oh, I'm so sorry—" he mumbled, aghast. English! Yes, of course. Here he was again and I didn't mind the blood at all, since at least this time he wasn't dying. Though of course I'd better do something about that nosebleed pretty fast.

So I led him back to my house. He leaned on me the whole way, only semiconscious most of the time. Unbelievable as it seemed, he'd apparently come through time without first taking any of the protective drugs that a mortal must have to make the journey safely. It was a miracle his brain wasn't leaking out his ears.

Three times I had to apply the coagulator wand to stop his bleeding. He drifted in and out of consciousness, and my floaty calm began to evaporate fast. I talked to him, trying to keep his attention. He was able to tell me that his name was Alec Checkerfield, but he wasn't sure about time or place. Possibly 2351? He did recognize the Company logo on my coveralls, and it seemed to alarm him. That was when I knew he'd stolen the shuttle, though I didn't acknowledge this to myself because such a thing was impossible. Just as it was impossible that a mortal being should be able to operate a time shuttle at all, or survive a temporal journey without drugs buffering him.

So I told him, to calm him down, that I was a prisoner here. That seemed to be the right thing to say, because he became confidential with me at once. It seems he knows all about the Company, has in fact some sort of grudge against them, something very mysterious he can't tell me about; but Dr. Zeus has, to use his phrase, wrecked his life, and he's out to bring them to their knees.

This was so demonstrably nuts that I concluded the crash had addled his brain a bit, but I said soothing and humoring things as I helped him inside and got him to stretch out on my bed, pushing a bench to the end so his feet wouldn't hang over. Just like old times, eh? And there he lay.

My crazed urge was to fall down weeping beside him and cover him with kisses, blood or no; but of course what I did was bring water and a towel to clean him up, calm and sensible. Mendoza the cyborg, in charge of her emotions, if not her mind.

It was still delight to stroke his face with the cool cloth, watch his pupils dilate or his eyes close in involuntary pleasure at the touch of the water. When I had set aside the basin I stayed with him, tracing the angle of his jaw with my hand, feeling the blood pulsing under his skin.

"You'll be all right now," I told him. "Your blood pressure and heart rate are normalizing. You're an extraordinary man, Alec Checkerfield."

"I'm an earl, too," he said proudly. "Seventh earl of Finsbury."

Oh, my, he'd come up in the world. Nicholas had been no more than secretary to a knight, and Edward—firmly shut out of the Victorian ruling classes by the scandal of his birth—had despised inherited privilege. "No, really, a British peer?" I said. "I don't think I've ever met a real aristocrat before."

"How long have you been stuck here?" he said. What was that accent of his? Not the well-bred Victorian inflection of last time; this was slangy, transatlantic, and decidedly limited in vocabulary. Did earls speak like this in the twenty-fourth century? Oh, how strange.

"I've been at this station for years," I answered him unguardedly. Oops. "More years than I remember." He looked understandably confused, since my immortal body stopped changing when I was twenty.

"You mean they marooned you here when you were just a kid? Bloody hell, what'd you do? It must have been something your parents did."

How close could I stick to the truth without frightening him?

"Not exactly. But I also knew too much about something I shouldn't have. Dr. Zeus found a nicely humane oubliette and dropped me out of sight or sound. You're the first mortal"—oops again—"soul I've spoken with in all this time."

"My God." He looked aghast. Then his eyes narrowed, I knew that look, that was his righteous wrath look. "Well, listen—er—what's your name, babe?"

Rosa? Dolores? No. No aliases anymore. "Mendoza," I said.

"Okay, Mendoza. I'll get you out of here," he said, all stern heroism. "That time shuttle out there is mine now, babe, and when I've finished this other thing I'll come back for you." He gripped my hand firmly.

Oh, no, I thought, what has he gotten himself into now? At what windmill has he decided to level his lance?

Summoning every ounce of composure, I frowned delicately and enunciated: "Do I understand you to say that you stole a time shuttle from Dr. Zeus Incorporated?"

"Yup," he said, with that sly sideways grin I knew so terribly well.

"How, in God's name? They're all powerful and all knowing, too. Nobody steals anything from the Company!" I said.

"I did," he said, looking so smug I wanted to shake him. "I've got sort of an advantage. At least, I had," he amended in a more subdued voice. "They may have killed my best friend. If he'd been with me, I wouldn't have crashed. I don't know what's happened to him, but if he's really gone … they will pay."

Something had persuaded this man that he could play the blood and revenge game with Dr. Zeus and win. He couldn't win, of course, for a number of reasons; not least of which was that every time shuttle has a theft intercept program built into it, which will at a predetermined moment detonate a hidden bomb to blow both shuttle and thief to atoms.

This was the fate Alec had been rushing to meet when he'd detoured into my field. I could see it now so clearly, it was sitting on his chest like a scorpion, and he was totally unaware it was there. I didn't even need to sit through the play this time; I'd been handed the synopsis in terrible brevity.

"But what do you think you can do?" I said.

"Wreck them. Bankrupt them. Expose what they've been doing. Tell the whole world the truth," Alec growled, in just the same voice in which Nicholas had used to rant about the Pope. He squeezed my hand more tightly.

I couldn't talk him out of it. I never can. I had to try, though.

"But—Alec. Do you have any idea what you're going up against? These people know everything that's ever happened, or at least they know abou

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...