- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

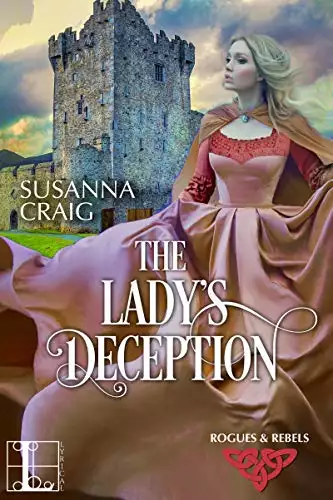

Synopsis

Can a runaway English bride find love with a haunted Irish rebel?

Paris Burke, Dublin’s most charismatic barrister, has enough on his mind without the worries of looking after his two youngest sisters. The aftermath of a failed rebellion weighs on his conscience, so when the young English gentlewoman with an unwavering gaze arrives, he asks far too few questions before hiring her on as governess. But her quick wit and mysterious past prove an unexpected temptation.

Rosamund Gorse knows she should not have let Mr. Burke think her the candidate from the employment bureau. But after her midnight escape from a brother bent on marrying her off to a scoundrel, honesty is a luxury she can no longer afford. With his clever mind and persuasive skill, Paris could soon have her spilling her secrets freely just to lift the sorrow from his face. And if words won’t work, perhaps kisses would be better?

Hiding under her brother’s nose, Rosamund knows she shouldn’t take risks. If Paris learns the truth, she might lose her freedom for good. But if she can learn to trust him with her heart, she might discover just the champion she desires . . .

Praise for Susanna Craig

“A stunning, sensual storyteller . . . evocative prose and richly drawn characters.”

—New York Times bestselling author Jennifer McQuiston

Paris Burke, Dublin’s most charismatic barrister, has enough on his mind without the worries of looking after his two youngest sisters. The aftermath of a failed rebellion weighs on his conscience, so when the young English gentlewoman with an unwavering gaze arrives, he asks far too few questions before hiring her on as governess. But her quick wit and mysterious past prove an unexpected temptation.

Rosamund Gorse knows she should not have let Mr. Burke think her the candidate from the employment bureau. But after her midnight escape from a brother bent on marrying her off to a scoundrel, honesty is a luxury she can no longer afford. With his clever mind and persuasive skill, Paris could soon have her spilling her secrets freely just to lift the sorrow from his face. And if words won’t work, perhaps kisses would be better?

Hiding under her brother’s nose, Rosamund knows she shouldn’t take risks. If Paris learns the truth, she might lose her freedom for good. But if she can learn to trust him with her heart, she might discover just the champion she desires . . .

Praise for Susanna Craig

“A stunning, sensual storyteller . . . evocative prose and richly drawn characters.”

—New York Times bestselling author Jennifer McQuiston

Release date: October 29, 2019

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 226

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Lady's Deception

Susanna Craig

Chapter 1

The ghost was the last straw.

Lord Dashfort’s two children, still grieving the loss of their mother, had been most unwelcoming. An orphan herself, Rosamund had tried to be understanding. She’d ignored the items that had disappeared from her trunk. Shrugged away a grimace when salt had been substituted for sugar in her tea. Swallowed her shriek of surprise when she’d found the half-dozen muddy toads in her bed—accompanied by an equally muddy set of child-sized footprints leading to and from her bedchamber.

But the spectral figure of a child drifting across the south lawn of Kilready Castle went well beyond the realm of an ordinary prank.

Within hours of her arrival at Kilready, Rosamund had begun to hear bits and pieces of the tragic story, whispered through the castle corridors in a brogue almost unintelligible to her English ear: servants’ tales of the tragic loss of Lord Dashfort’s first son, brought into the world too soon. As soon as she’d been able to travel, Lady Dashfort had left for London, declaring she meant never to return to her husband’s Irish estate. The grief-stricken earl had followed her. The servants swore he’d been driven away by the ghostly sounds of babbling in an empty nursery. In the years that had followed, the legend had grown with the lost child. Unexplained footsteps in an abandoned schoolroom, books knocked askew by an unknown hand. And now the shadowy form of a boy who walked the castle grounds on moonlit nights.

Rosamund had been accused of imagining things so often, she was inclined to doubt the proof of her own eyes. But she felt certain she was not imagining this. Not that she believed in ghosts. No, her first reaction to the sight was more disappointment than fear. She liked children. She might have bonded with Alexander and Eugenia over their shared experience of loss. Instead, the two of them had plotted and planned to give her a fright.

In the evenings, after she’d readied for bed, Rosamund often sat by the large window in her chamber, studying the choppy water of the Irish Sea. Now and again, she fancied she caught a glimpse of the neighboring island and wondered how things got on at home. The children had obviously discovered her habit.

As if expecting to find her at the window, a boy who could only be Alexander paused in his progress and looked up, his pointed face unearthly pale. An effect of the moonlight, which bathed everything it touched in pearly luminescence. Still, she shivered and clutched her shawl closer—afraid not of a specter, but of the steep cliff that lay just beyond the scrub into which the boy was now disappearing. How easily he might lose his footing and tumble into the sea. With a soft yelp of alarm, she leaped to her feet and hurried out of her room.

The stairwell, aglow with that same strange light, sent another chill through her. She refused to allow her eyes to dart into corners or to examine the oddly-shaped shadows that stretched up the walls. Her hurried footsteps whispered across the flagstones, and in a few moments she was standing on the threshold of the nursery.

Two child-sized lumps filled two child-sized beds, and in the corner their nurse nodded over some sewing. Sparing nothing more than a frown for the woman’s inattention, Rosamund stepped to the bed on the left-hand side of the room.

“Eugenia.” A whisper, but only just, and harsh with fear. “Eugenia.” A shake this time, and at last the lump stirred. “What can you and your brother have been thinking? Where is he now?”

“Xander?” Eugenia mumbled in a fair imitation of drowsiness. Tousled brown curls made an appearance from beneath the bedclothes, followed by a pair of eyes puffy with sleep. Still, Rosamund was not convinced of either the girl’s ignorance of her brother’s whereabouts or her innocence in this scheme. Though she was only just seven, she was unquestionably the leader of the pair, considerably more hardened than her soft hair and lisping voice suggested. Alexander—diffident, quiet, and hardly taller than his sister—was far too squeamish to catch toads. She could only guess what coercions had been required to convince him to take a midnight stroll across the lawn.

“What is it, Miss Gorse? Is Xenia ill?”

The sound of Alexander’s muffled voice, coming from the neighboring bed, nearly sent Rosamund to the floor.

After a few ineffectual swats, the boy managed to paw the blankets away from his face and sat up, his blond hair sticking out at all angles and his rumpled nightshirt clinging to his slight frame. Unless he had developed the powers of flight, he could not have made it to the nursery ahead of her, changed into his nightclothes, and climbed into bed. Yet there he sat.

Rosamund could not keep herself from reaching out to reassure herself he was not a specter, excusing the action by brushing the hair from his pale, pinched brow.

If Alexander was in the nursery, who—or what—had she seen on the lawn?

Had she perhaps dreamed the whole thing, dozed for a moment and fallen into a nightmare fueled by the ghoulish gossip of the castle’s servants? Her brother was always chiding her flights of fancy.

Or had the boy been a villager, bent on poaching or stealing? There seemed to be any number of desperate people in the vicinity of Kilready, and midnight was an hour for mischief. Perhaps she ought to tell someone what she’d seen. But who would believe her? And if by chance someone did, well… Justice would not be served by sending a poor child either to the noose or to New South Wales.

“Why, Miss Gorse.”

Lord Dashfort’s voice made her jerk as if struck. She turned to find him standing in the doorway of the nursery, her shawl gathered in his hands. Reflexively, she felt for it around her shoulders. When had it slipped away?

“How kind of you to come up to wish the children good night,” he said, his eyes traveling over her lightly-clad form.

“What’s this? What’s this?” The nurse bustled toward them, shaking off sleep more quickly than the children. “Who’s feelin’ poorly?”

“No one,” Rosamund said. “No one. I came because—” With a little shake, she broke off. How could she possibly explain why she’d come? What she’d seen? Or thought she had…

“Why are you here, Father?” Alexander demanded.

Lord Dashfort’s chuckle did not disguise his annoyance. “You must be half asleep, my boy. Don’t I always come and wish you and your sister good night?”

The surprised faces of both the nurse and the children persuaded Rosamund that the answer was no.

Nevertheless, Lord Dashfort approached. In a strikingly awkward economy of affection, the earl patted his son on the head with his free hand, at the same time leaning toward his daughter for a kiss. Eugenia squirmed away, her eyes still fixed on Rosamund. “Are you quite well, Miss Gorse?” she said. “You look as if you’d seen a ghost.”

“I daresay she’s simply cold.” Lord Dashfort straightened and turned, unfolding Rosamund’s shawl as he spoke. Under pretense of assisting her with it, his arm came around her shoulders and did not leave. “Come, Miss Gorse. Let me escort you back to your chamber. It’s easy enough to lose one’s way in this old pile, especially after dark.” He paid little heed to his children’s murmured “good nights” or the nurse’s curtsy as he steered Rosamund from the room.

Several times as they walked along, she shrugged, trying and failing to dislodge his arm. “Why, you’re shivering, my dear Miss Gorse. I hope you haven’t taken a chill.”

“I’m fine,” Rosamund insisted. Or rather, tried to insist. Even to her own ears, her voice lacked all conviction.

“And Eugenia was right. You are pale. Though,” he added wryly, “one wishes she had chosen some other simile.”

“Yes.” Rosamund hesitated. “Although, in truth, I did see something—”

“Have my children been repeating the servants’ ridiculous stories to you?” His accompanying sigh was deep, and his shoulders must have sunk with it. His arm grew heavier still. “Clearly, they need a steadying hand, the influence of a sensible woman.” He paused and gazed down at her. “Poor motherless things…”

They had reached the corridor in which her chamber was located. “I wish you good luck in finding such a woman, my lord. I do believe this place could turn the soberest mind.” Her words appeared to take him aback, giving her another opportunity to make a bid for freedom. “I will say good night.”

His grip on her shoulders tightened. “So soon?”

“It’s very late.”

His other arm came around her, caging her between his body and the wall. Her shawl was no barrier to the chill of the stones against her back. Instinctively, her hand rose to his chest and she tried to push him away.

“Come now, Miss Gorse. Surely you will not deny your future husband a good night kiss?”

He had stopped beneath an unlit sconce, casting his expression in shadow. But he must be teasing her. Future husband? Much as she might long for a family, marriage to Lord Dashfort was the furthest thing from her mind. Why, the earl was her brother’s old school chum, more than twice her age. Worse yet, he—

In the near darkness, his hot, moist mouth grazed her cheek, bringing with it the stench of brandy and mushroom ragout and making her stomach churn. Twisting sharply, she winced as the rough stone snagged her shawl and dug into her skin. “Lord Dashfort, unhand me this instant!”

He relented, but not because of her words. Farther down the corridor, a discreet, masculine cough had broken the stillness.

“Charles,” she gasped, slipping away from a stunned Lord Dashfort and hurrying toward her brother.

Her brother regarded her coolly, arms crossed over his chest. “You should be in bed, Rosie.”

Arrested in her flight, she rocked back on her heels, thinking of Alexander and Eugenia’s pet names for one another. She was only ever Rosie when Charles was unhappy with her. Which was most of the time.

“Yes, Charles.” With a backward glance at Lord Dashfort, she slipped into her room.

Hardly had the door closed behind her when Charles spoke.

“I am appalled, Dashfort.”

For just a moment, foolish hope sparked within her. Of course her brother would defend her honor. Only…only instead of reprimanding Lord Dashfort’s shocking conduct, Charles sounded…bored?

“Setterby.” Lord Dashfort’s voice was little more than a growl. If she didn’t know better, she would have thought that the earl and her brother were enemies, rather than friends. “It was your suggestion that I begin to accustom her to the idea of our marriage.”

“Yes,” said Charles, and the tiny flicker of hope in her breast sputtered. The earl had not been teasing her, after all. No wonder he’d been so inordinately attentive to her during their visit. No wonder the children had been on their worst behavior. They resented their father’s plan to remarry. They were doing all they could to prevent their mother’s place from being usurped.

How naïve she’d been.

“But I have no intention of allowing you to anticipate the wedding night,” continued her brother, chiding.

It was not difficult to imagine herself trapped in the unwelcome embrace of an old—well, almost old—man with foul breath and clammy hands and one wife already in the grave. Her shudder rattled the door against which she leaned.

Undisturbed by the sound, her brother continued speaking. “At least, not until I have the money in hand…”

The chill in his voice snuffed the last embers of hope. Money? Had she gone back in time when she’d crossed beneath the portcullis of Kilready Castle? Returned to some feudal age? It seemed Charles had done more than arrange what he imagined to be an advantageous match on behalf of his sister. It sounded for all the world as if her brother were trying to sell her!

Of course, he was forever bemoaning the state of the family finances. But how on earth had he persuaded anyone to pay for the privilege of wedding her?

And what might the earl expect of her in exchange?

She quelled another shudder. Her brother did not like to be gainsaid, as she well knew. But this time she was going to have to put her foot down.

“We agreed on Lady Day,” Lord Dashfort was quick to remind him, forgetting to whisper. “I’ve spoken to Quin, my agent. The new rents will be more than enough to meet your price.”

“If your tenants come up to scratch,” Charles sneered.

“They haven’t much choice, have they?” Lord Dashfort’s voice was an odd mixture of anger, desperation, and…guilt?

“From what I’ve seen, they haven’t much of anything. Except, that is, for the wily Mr. Quin.”

“He’s none of your concern,” snapped the earl. “You’ll have your money on Monday, Setterby. And on Tuesday—”

“On Tuesday, Rosamund will be yours to deal with.” A low laugh. “However you see fit.”

Despite herself, she hissed in a sharp breath at his dismissive words. Everyone knew that the first Lady Dashfort had died under suspicious circumstances. She might be Charles’s mere half-sister, but didn’t he care at all for what became of her? Since their father’s will had named him her guardian, she had come to expect Charles’s indifference. But this?

Slowly she backed away from the door. The door with no lock to protect her. And if she didn’t act quickly, she might find herself a prisoner at Kilready Castle, with or without a lock.

Before the echo of Lord Dashfort’s footsteps had entirely faded away, she turned and walked to the armoire. With one finger, she riffled through the dresses hanging there: elegant silks, soft woolens. Time and again Charles had told her he only wanted what was best for her. Like this visit to an old friend in Ireland.

Too far from home for her to resist what he had planned?

Quickly, she removed her nightgown, and slipped into the only dress she owned that did not require a corset or a maid’s assistance. She had been under her brother’s protection for most of her life. Or thought she had. Now, however, she was going to have to find a way to escape it.

Once clad in an airy confection of muslin in the newest style, far more suited to a ballroom than the outing she was about to undertake, she closed the inlaid door of the wardrobe with a snap. The weight of a bag of fine dresses would only hinder her getaway.

But where would she go? A sympathetic clergyman might be persuaded to take her in. Then again, perhaps it was only in novels that such gentlemen provided sanctuary to unfortunate women. She needed someone bold—or reckless—enough to challenge her brother over the matter of his guardianship. After all, she was nearly one and twenty, almost of an age to take responsibility for herself…though she hadn’t the slightest idea how to begin.

So, a lawyer? But she had nothing to offer such a man as compensation for his services. Charles controlled the family purse strings.

Well, she would have to find a way to do without money. If she could make her way to Dublin, surely someone would help her.

In a fit of resolve, she strode to the window. The full moon had risen higher, casting a glow almost as bright as daylight. Far below on the lawn, all was quiet. She let her eyes roam over the stretch of velvety grass and peer into the shadows beneath the shrubbery. Nothing. Not even a tomcat on the prowl. What had she seen?

A servant boy, or some child from the village. She must have imagined the resemblance. But when she tried to call up the unknown boy’s face, even her mind’s eye seemed determined to betray her. She could see only Alexander, or a child enough like him to be his—

Nonsense. Alexander’s only sibling was Eugenia. And Rosamund did not intend to be party to any arrangement that might give him another.

Stretching out her arm, she caught the shutter, jerked it inward, and latched it tight, throwing the chamber into darkness.

Chapter 2

At the knelling of church bells, Paris Burke swore—blasphemy, no doubt, but what did it matter? He was damned already.

He paused in his descent from Constitution Hill to shake the sound from his head. The call to Evensong at Christchurch? Surely not. The waters of the Liffey must be making the bells echo, doubling their peals. It could not possibly be as late as…

He pulled his watch from his waistcoat pocket, tilted its face toward the fading sunlight, and at its confirmation of the hour, swore again.

During the years of his life when he might have offered ample excuses for running late—the combined and sometimes competing demands of the law and his hopes for Ireland’s liberation—only once had he failed to keep an assignation. The disastrous effects of that mistake would haunt him for the rest of his days. Fortunately, the consequences of missing an appointment with Mrs. Fitzhugh were not so dire. Nonetheless, he regretted what it revealed about the kind of man he’d become.

Tucking the watch away, he glanced over his shoulder in the direction of King’s Inns—not with longing, precisely. Oh, the dinner in the commons had been good enough, and the wine had flowed freely. Time was, the company alone would have been enough to call him back. The brotherhood of jurisprudence. The discussions, the debates.

Tonight, though, he had felt certain absences too strongly. The faces that could no longer join them. The voices that would never be heard again. No matter how many times he had signaled for his cup to be filled, their ghostly shadows had refused to be dispelled.

For the first time, he was not sorry he’d been forced to give up his lodgings closer to the courts. The walk across the city would help to clear his head. And give him time to concoct some explanation for his lateness, though whatever he produced would do little to blunt the disappointment with which he was bound to be greeted.

He took another half-dozen strides, rounding the corner of Church Street to pass in front of the Four Courts. The last of the daylight cast a jagged chiaroscuro across the ground, the building itself too new for its shadows to have grown familiar to his eyes. From the gloom, something slipped into his path. What sort of claret had they been pouring, that it continued to conjure these spectral apparitions, this one with pale hair and paler skin? He swore a third time.

“You ought to mind your tongue in the presence of a lady,” the wraith said primly, stepping into the light and resolving itself into the perfectly ordinary figure of a blonde woman wearing a pelisse the color of Portland stone.

No, not perfectly ordinary. Perfectly ordinary women did not materialize on the King’s Inns Quay. They did not have hair the color of summer butter, spilling from beneath a ridiculous frippery of a hat that looked a little worse for wear. Nor did they have eyes the color of—well, no sea he had ever had the pleasure to know. With another shake of his head, he stepped closer, finding himself in need of the support of hewn granite.

“I’m looking for someone,” she said, warily watching his every move. Her brows knitted themselves into a tight frown. “A lawyer. You see, I—”

“You’re English.” Part observation, part accusation. She wasn’t the first beautiful woman his fancy had invented, but never before had his imagination betrayed his politics so thoroughly.

“I’m Miss Gorse,” she replied, as if that decided the matter.

Oddly enough, it did. Because only a real woman could have such a prickly name. And such a prickly voice. Which, heaven help him, was still speaking.

“—and his two children—”

Damn it all. His sisters. He’d promised them, when the last interview had turned up no likely candidate, that Mrs. Fitzhugh would surely know of someone suitable. And now he’d have to confess that he’d—

A tongue of wind licked along the river, rippling the water before gusting up the face of the imposing edifice in whose shelter they stood. He pushed himself up a little straighter, bolstered as much by the cool air as by the cornerstone’s sharp edge where it fitted neatly along the groove of his spine.

Two children… Was it possible? He’d understood the meeting with Mrs. Fitzhugh to be preliminary, but perhaps she had not waited to speak with him before deciding on the right person for the job.

“You’re looking for a lawyer, you say?”

Her mouth, already forming other words, hung open a moment before shaping an answer to his question. “Yes. I thought—”

“Mrs. Fitzhugh sent you to find Mr. Burke at King’s Inns, I gather.”

“Er—”

“Well, you’ve found him. I’m Paris Burke. Barrister. Of course, you’ll really be in my father’s employ. A man without children isn’t likely to need a governess, now is he?” His wry laugh ricocheted off the stone walls, startling a flock of drowsy rooks who cawed their disapproval.

Her lips were parted once again, but this time no words came. She was watching him with wide eyes that did not narrow, even when she at last closed her mouth and jerked her head in some uncertain motion, neither disagreement nor agreement.

“My sisters will be delighted to meet you, Miss Gorse. I am surprised, though, that Mrs. Fitzhugh didn’t send you directly to Merrion Square.”

“I don’t—” She paused, wetted her lips, and appeared to weigh her reply before beginning again. “Is it far?”

“No more than a mile. An English mile, to be precise,” he added, curving his mouth into a sort of smile. He would not have guessed that Mrs. Fitzhugh had a sense of humor. To send him, of all people, an Englishwoman… “At least we’ve a fine night for a stroll.”

After a moment’s hesitation, she dipped her head in a nod. “Indeed, Mr. Burke. I had no thought this morning that the day would take a turn for the better.”

“Ah, well. It mightn’t’ve, you know.” Turning, he set off along the quayside. “An Irish spring is not to be predicted.”

“This is my first,” she said. “My first Irish spring, that is.”

Last spring, then, she’d been elsewhere. In England, presumably. Far from the turmoil that had enveloped Dublin and the surrounding countryside. Far from the rebellion that had taken the lives of so many. And for what? For naught, for naught…

The warm glow of the claret guttered like a candle, struggling to withstand the damp, clammy mist rising from the Liffey. He had not realized he had lengthened his stride until he heard the sounds of someone struggling to keep up.

“Mr. Burke?” She had one hand pressed to her side and a hitch in her gait. “I wonder if we might walk a bit more slowly.”

When she reached his side, he held out his free arm and she took it, not with the perfunctory brush of her fingertips, but with her whole hand, leaning heavily against him. Odd. She was petite, but she didn’t look frail. “Shall I hail a sedan chair, Miss Gorse?” Though truthfully, this was an unlikely spot to hail anything but trouble. And the more he thought of Mrs. Fitzhugh directing a woman to meet him here, in this fashion, the less he liked it. Why, he might have been detained at commons for hours, and she left alone as darkness fell…

Her touch lightened as she bristled. “I can walk.” Her step was almost brisk as they crossed the Carlisle Bridge. “So you’re in need of a governess?”

“For my sisters. Daphne and Bellis. Aged ten and eight, respectively. You’ll find them as ignorant as most girls their age, I daresay.”

She drew back her shoulders at that description. “Their previous governess was not firm enough with them?”

“I’m almost embarrassed to admit it, but they haven’t any previous governess. They are the youngest of the six of us and shockingly spoiled. My father in particular has always been prone to indulgence where they were concerned.”

Some emotion—he hesitated to call it disapproval—sketched acro. . .

The ghost was the last straw.

Lord Dashfort’s two children, still grieving the loss of their mother, had been most unwelcoming. An orphan herself, Rosamund had tried to be understanding. She’d ignored the items that had disappeared from her trunk. Shrugged away a grimace when salt had been substituted for sugar in her tea. Swallowed her shriek of surprise when she’d found the half-dozen muddy toads in her bed—accompanied by an equally muddy set of child-sized footprints leading to and from her bedchamber.

But the spectral figure of a child drifting across the south lawn of Kilready Castle went well beyond the realm of an ordinary prank.

Within hours of her arrival at Kilready, Rosamund had begun to hear bits and pieces of the tragic story, whispered through the castle corridors in a brogue almost unintelligible to her English ear: servants’ tales of the tragic loss of Lord Dashfort’s first son, brought into the world too soon. As soon as she’d been able to travel, Lady Dashfort had left for London, declaring she meant never to return to her husband’s Irish estate. The grief-stricken earl had followed her. The servants swore he’d been driven away by the ghostly sounds of babbling in an empty nursery. In the years that had followed, the legend had grown with the lost child. Unexplained footsteps in an abandoned schoolroom, books knocked askew by an unknown hand. And now the shadowy form of a boy who walked the castle grounds on moonlit nights.

Rosamund had been accused of imagining things so often, she was inclined to doubt the proof of her own eyes. But she felt certain she was not imagining this. Not that she believed in ghosts. No, her first reaction to the sight was more disappointment than fear. She liked children. She might have bonded with Alexander and Eugenia over their shared experience of loss. Instead, the two of them had plotted and planned to give her a fright.

In the evenings, after she’d readied for bed, Rosamund often sat by the large window in her chamber, studying the choppy water of the Irish Sea. Now and again, she fancied she caught a glimpse of the neighboring island and wondered how things got on at home. The children had obviously discovered her habit.

As if expecting to find her at the window, a boy who could only be Alexander paused in his progress and looked up, his pointed face unearthly pale. An effect of the moonlight, which bathed everything it touched in pearly luminescence. Still, she shivered and clutched her shawl closer—afraid not of a specter, but of the steep cliff that lay just beyond the scrub into which the boy was now disappearing. How easily he might lose his footing and tumble into the sea. With a soft yelp of alarm, she leaped to her feet and hurried out of her room.

The stairwell, aglow with that same strange light, sent another chill through her. She refused to allow her eyes to dart into corners or to examine the oddly-shaped shadows that stretched up the walls. Her hurried footsteps whispered across the flagstones, and in a few moments she was standing on the threshold of the nursery.

Two child-sized lumps filled two child-sized beds, and in the corner their nurse nodded over some sewing. Sparing nothing more than a frown for the woman’s inattention, Rosamund stepped to the bed on the left-hand side of the room.

“Eugenia.” A whisper, but only just, and harsh with fear. “Eugenia.” A shake this time, and at last the lump stirred. “What can you and your brother have been thinking? Where is he now?”

“Xander?” Eugenia mumbled in a fair imitation of drowsiness. Tousled brown curls made an appearance from beneath the bedclothes, followed by a pair of eyes puffy with sleep. Still, Rosamund was not convinced of either the girl’s ignorance of her brother’s whereabouts or her innocence in this scheme. Though she was only just seven, she was unquestionably the leader of the pair, considerably more hardened than her soft hair and lisping voice suggested. Alexander—diffident, quiet, and hardly taller than his sister—was far too squeamish to catch toads. She could only guess what coercions had been required to convince him to take a midnight stroll across the lawn.

“What is it, Miss Gorse? Is Xenia ill?”

The sound of Alexander’s muffled voice, coming from the neighboring bed, nearly sent Rosamund to the floor.

After a few ineffectual swats, the boy managed to paw the blankets away from his face and sat up, his blond hair sticking out at all angles and his rumpled nightshirt clinging to his slight frame. Unless he had developed the powers of flight, he could not have made it to the nursery ahead of her, changed into his nightclothes, and climbed into bed. Yet there he sat.

Rosamund could not keep herself from reaching out to reassure herself he was not a specter, excusing the action by brushing the hair from his pale, pinched brow.

If Alexander was in the nursery, who—or what—had she seen on the lawn?

Had she perhaps dreamed the whole thing, dozed for a moment and fallen into a nightmare fueled by the ghoulish gossip of the castle’s servants? Her brother was always chiding her flights of fancy.

Or had the boy been a villager, bent on poaching or stealing? There seemed to be any number of desperate people in the vicinity of Kilready, and midnight was an hour for mischief. Perhaps she ought to tell someone what she’d seen. But who would believe her? And if by chance someone did, well… Justice would not be served by sending a poor child either to the noose or to New South Wales.

“Why, Miss Gorse.”

Lord Dashfort’s voice made her jerk as if struck. She turned to find him standing in the doorway of the nursery, her shawl gathered in his hands. Reflexively, she felt for it around her shoulders. When had it slipped away?

“How kind of you to come up to wish the children good night,” he said, his eyes traveling over her lightly-clad form.

“What’s this? What’s this?” The nurse bustled toward them, shaking off sleep more quickly than the children. “Who’s feelin’ poorly?”

“No one,” Rosamund said. “No one. I came because—” With a little shake, she broke off. How could she possibly explain why she’d come? What she’d seen? Or thought she had…

“Why are you here, Father?” Alexander demanded.

Lord Dashfort’s chuckle did not disguise his annoyance. “You must be half asleep, my boy. Don’t I always come and wish you and your sister good night?”

The surprised faces of both the nurse and the children persuaded Rosamund that the answer was no.

Nevertheless, Lord Dashfort approached. In a strikingly awkward economy of affection, the earl patted his son on the head with his free hand, at the same time leaning toward his daughter for a kiss. Eugenia squirmed away, her eyes still fixed on Rosamund. “Are you quite well, Miss Gorse?” she said. “You look as if you’d seen a ghost.”

“I daresay she’s simply cold.” Lord Dashfort straightened and turned, unfolding Rosamund’s shawl as he spoke. Under pretense of assisting her with it, his arm came around her shoulders and did not leave. “Come, Miss Gorse. Let me escort you back to your chamber. It’s easy enough to lose one’s way in this old pile, especially after dark.” He paid little heed to his children’s murmured “good nights” or the nurse’s curtsy as he steered Rosamund from the room.

Several times as they walked along, she shrugged, trying and failing to dislodge his arm. “Why, you’re shivering, my dear Miss Gorse. I hope you haven’t taken a chill.”

“I’m fine,” Rosamund insisted. Or rather, tried to insist. Even to her own ears, her voice lacked all conviction.

“And Eugenia was right. You are pale. Though,” he added wryly, “one wishes she had chosen some other simile.”

“Yes.” Rosamund hesitated. “Although, in truth, I did see something—”

“Have my children been repeating the servants’ ridiculous stories to you?” His accompanying sigh was deep, and his shoulders must have sunk with it. His arm grew heavier still. “Clearly, they need a steadying hand, the influence of a sensible woman.” He paused and gazed down at her. “Poor motherless things…”

They had reached the corridor in which her chamber was located. “I wish you good luck in finding such a woman, my lord. I do believe this place could turn the soberest mind.” Her words appeared to take him aback, giving her another opportunity to make a bid for freedom. “I will say good night.”

His grip on her shoulders tightened. “So soon?”

“It’s very late.”

His other arm came around her, caging her between his body and the wall. Her shawl was no barrier to the chill of the stones against her back. Instinctively, her hand rose to his chest and she tried to push him away.

“Come now, Miss Gorse. Surely you will not deny your future husband a good night kiss?”

He had stopped beneath an unlit sconce, casting his expression in shadow. But he must be teasing her. Future husband? Much as she might long for a family, marriage to Lord Dashfort was the furthest thing from her mind. Why, the earl was her brother’s old school chum, more than twice her age. Worse yet, he—

In the near darkness, his hot, moist mouth grazed her cheek, bringing with it the stench of brandy and mushroom ragout and making her stomach churn. Twisting sharply, she winced as the rough stone snagged her shawl and dug into her skin. “Lord Dashfort, unhand me this instant!”

He relented, but not because of her words. Farther down the corridor, a discreet, masculine cough had broken the stillness.

“Charles,” she gasped, slipping away from a stunned Lord Dashfort and hurrying toward her brother.

Her brother regarded her coolly, arms crossed over his chest. “You should be in bed, Rosie.”

Arrested in her flight, she rocked back on her heels, thinking of Alexander and Eugenia’s pet names for one another. She was only ever Rosie when Charles was unhappy with her. Which was most of the time.

“Yes, Charles.” With a backward glance at Lord Dashfort, she slipped into her room.

Hardly had the door closed behind her when Charles spoke.

“I am appalled, Dashfort.”

For just a moment, foolish hope sparked within her. Of course her brother would defend her honor. Only…only instead of reprimanding Lord Dashfort’s shocking conduct, Charles sounded…bored?

“Setterby.” Lord Dashfort’s voice was little more than a growl. If she didn’t know better, she would have thought that the earl and her brother were enemies, rather than friends. “It was your suggestion that I begin to accustom her to the idea of our marriage.”

“Yes,” said Charles, and the tiny flicker of hope in her breast sputtered. The earl had not been teasing her, after all. No wonder he’d been so inordinately attentive to her during their visit. No wonder the children had been on their worst behavior. They resented their father’s plan to remarry. They were doing all they could to prevent their mother’s place from being usurped.

How naïve she’d been.

“But I have no intention of allowing you to anticipate the wedding night,” continued her brother, chiding.

It was not difficult to imagine herself trapped in the unwelcome embrace of an old—well, almost old—man with foul breath and clammy hands and one wife already in the grave. Her shudder rattled the door against which she leaned.

Undisturbed by the sound, her brother continued speaking. “At least, not until I have the money in hand…”

The chill in his voice snuffed the last embers of hope. Money? Had she gone back in time when she’d crossed beneath the portcullis of Kilready Castle? Returned to some feudal age? It seemed Charles had done more than arrange what he imagined to be an advantageous match on behalf of his sister. It sounded for all the world as if her brother were trying to sell her!

Of course, he was forever bemoaning the state of the family finances. But how on earth had he persuaded anyone to pay for the privilege of wedding her?

And what might the earl expect of her in exchange?

She quelled another shudder. Her brother did not like to be gainsaid, as she well knew. But this time she was going to have to put her foot down.

“We agreed on Lady Day,” Lord Dashfort was quick to remind him, forgetting to whisper. “I’ve spoken to Quin, my agent. The new rents will be more than enough to meet your price.”

“If your tenants come up to scratch,” Charles sneered.

“They haven’t much choice, have they?” Lord Dashfort’s voice was an odd mixture of anger, desperation, and…guilt?

“From what I’ve seen, they haven’t much of anything. Except, that is, for the wily Mr. Quin.”

“He’s none of your concern,” snapped the earl. “You’ll have your money on Monday, Setterby. And on Tuesday—”

“On Tuesday, Rosamund will be yours to deal with.” A low laugh. “However you see fit.”

Despite herself, she hissed in a sharp breath at his dismissive words. Everyone knew that the first Lady Dashfort had died under suspicious circumstances. She might be Charles’s mere half-sister, but didn’t he care at all for what became of her? Since their father’s will had named him her guardian, she had come to expect Charles’s indifference. But this?

Slowly she backed away from the door. The door with no lock to protect her. And if she didn’t act quickly, she might find herself a prisoner at Kilready Castle, with or without a lock.

Before the echo of Lord Dashfort’s footsteps had entirely faded away, she turned and walked to the armoire. With one finger, she riffled through the dresses hanging there: elegant silks, soft woolens. Time and again Charles had told her he only wanted what was best for her. Like this visit to an old friend in Ireland.

Too far from home for her to resist what he had planned?

Quickly, she removed her nightgown, and slipped into the only dress she owned that did not require a corset or a maid’s assistance. She had been under her brother’s protection for most of her life. Or thought she had. Now, however, she was going to have to find a way to escape it.

Once clad in an airy confection of muslin in the newest style, far more suited to a ballroom than the outing she was about to undertake, she closed the inlaid door of the wardrobe with a snap. The weight of a bag of fine dresses would only hinder her getaway.

But where would she go? A sympathetic clergyman might be persuaded to take her in. Then again, perhaps it was only in novels that such gentlemen provided sanctuary to unfortunate women. She needed someone bold—or reckless—enough to challenge her brother over the matter of his guardianship. After all, she was nearly one and twenty, almost of an age to take responsibility for herself…though she hadn’t the slightest idea how to begin.

So, a lawyer? But she had nothing to offer such a man as compensation for his services. Charles controlled the family purse strings.

Well, she would have to find a way to do without money. If she could make her way to Dublin, surely someone would help her.

In a fit of resolve, she strode to the window. The full moon had risen higher, casting a glow almost as bright as daylight. Far below on the lawn, all was quiet. She let her eyes roam over the stretch of velvety grass and peer into the shadows beneath the shrubbery. Nothing. Not even a tomcat on the prowl. What had she seen?

A servant boy, or some child from the village. She must have imagined the resemblance. But when she tried to call up the unknown boy’s face, even her mind’s eye seemed determined to betray her. She could see only Alexander, or a child enough like him to be his—

Nonsense. Alexander’s only sibling was Eugenia. And Rosamund did not intend to be party to any arrangement that might give him another.

Stretching out her arm, she caught the shutter, jerked it inward, and latched it tight, throwing the chamber into darkness.

Chapter 2

At the knelling of church bells, Paris Burke swore—blasphemy, no doubt, but what did it matter? He was damned already.

He paused in his descent from Constitution Hill to shake the sound from his head. The call to Evensong at Christchurch? Surely not. The waters of the Liffey must be making the bells echo, doubling their peals. It could not possibly be as late as…

He pulled his watch from his waistcoat pocket, tilted its face toward the fading sunlight, and at its confirmation of the hour, swore again.

During the years of his life when he might have offered ample excuses for running late—the combined and sometimes competing demands of the law and his hopes for Ireland’s liberation—only once had he failed to keep an assignation. The disastrous effects of that mistake would haunt him for the rest of his days. Fortunately, the consequences of missing an appointment with Mrs. Fitzhugh were not so dire. Nonetheless, he regretted what it revealed about the kind of man he’d become.

Tucking the watch away, he glanced over his shoulder in the direction of King’s Inns—not with longing, precisely. Oh, the dinner in the commons had been good enough, and the wine had flowed freely. Time was, the company alone would have been enough to call him back. The brotherhood of jurisprudence. The discussions, the debates.

Tonight, though, he had felt certain absences too strongly. The faces that could no longer join them. The voices that would never be heard again. No matter how many times he had signaled for his cup to be filled, their ghostly shadows had refused to be dispelled.

For the first time, he was not sorry he’d been forced to give up his lodgings closer to the courts. The walk across the city would help to clear his head. And give him time to concoct some explanation for his lateness, though whatever he produced would do little to blunt the disappointment with which he was bound to be greeted.

He took another half-dozen strides, rounding the corner of Church Street to pass in front of the Four Courts. The last of the daylight cast a jagged chiaroscuro across the ground, the building itself too new for its shadows to have grown familiar to his eyes. From the gloom, something slipped into his path. What sort of claret had they been pouring, that it continued to conjure these spectral apparitions, this one with pale hair and paler skin? He swore a third time.

“You ought to mind your tongue in the presence of a lady,” the wraith said primly, stepping into the light and resolving itself into the perfectly ordinary figure of a blonde woman wearing a pelisse the color of Portland stone.

No, not perfectly ordinary. Perfectly ordinary women did not materialize on the King’s Inns Quay. They did not have hair the color of summer butter, spilling from beneath a ridiculous frippery of a hat that looked a little worse for wear. Nor did they have eyes the color of—well, no sea he had ever had the pleasure to know. With another shake of his head, he stepped closer, finding himself in need of the support of hewn granite.

“I’m looking for someone,” she said, warily watching his every move. Her brows knitted themselves into a tight frown. “A lawyer. You see, I—”

“You’re English.” Part observation, part accusation. She wasn’t the first beautiful woman his fancy had invented, but never before had his imagination betrayed his politics so thoroughly.

“I’m Miss Gorse,” she replied, as if that decided the matter.

Oddly enough, it did. Because only a real woman could have such a prickly name. And such a prickly voice. Which, heaven help him, was still speaking.

“—and his two children—”

Damn it all. His sisters. He’d promised them, when the last interview had turned up no likely candidate, that Mrs. Fitzhugh would surely know of someone suitable. And now he’d have to confess that he’d—

A tongue of wind licked along the river, rippling the water before gusting up the face of the imposing edifice in whose shelter they stood. He pushed himself up a little straighter, bolstered as much by the cool air as by the cornerstone’s sharp edge where it fitted neatly along the groove of his spine.

Two children… Was it possible? He’d understood the meeting with Mrs. Fitzhugh to be preliminary, but perhaps she had not waited to speak with him before deciding on the right person for the job.

“You’re looking for a lawyer, you say?”

Her mouth, already forming other words, hung open a moment before shaping an answer to his question. “Yes. I thought—”

“Mrs. Fitzhugh sent you to find Mr. Burke at King’s Inns, I gather.”

“Er—”

“Well, you’ve found him. I’m Paris Burke. Barrister. Of course, you’ll really be in my father’s employ. A man without children isn’t likely to need a governess, now is he?” His wry laugh ricocheted off the stone walls, startling a flock of drowsy rooks who cawed their disapproval.

Her lips were parted once again, but this time no words came. She was watching him with wide eyes that did not narrow, even when she at last closed her mouth and jerked her head in some uncertain motion, neither disagreement nor agreement.

“My sisters will be delighted to meet you, Miss Gorse. I am surprised, though, that Mrs. Fitzhugh didn’t send you directly to Merrion Square.”

“I don’t—” She paused, wetted her lips, and appeared to weigh her reply before beginning again. “Is it far?”

“No more than a mile. An English mile, to be precise,” he added, curving his mouth into a sort of smile. He would not have guessed that Mrs. Fitzhugh had a sense of humor. To send him, of all people, an Englishwoman… “At least we’ve a fine night for a stroll.”

After a moment’s hesitation, she dipped her head in a nod. “Indeed, Mr. Burke. I had no thought this morning that the day would take a turn for the better.”

“Ah, well. It mightn’t’ve, you know.” Turning, he set off along the quayside. “An Irish spring is not to be predicted.”

“This is my first,” she said. “My first Irish spring, that is.”

Last spring, then, she’d been elsewhere. In England, presumably. Far from the turmoil that had enveloped Dublin and the surrounding countryside. Far from the rebellion that had taken the lives of so many. And for what? For naught, for naught…

The warm glow of the claret guttered like a candle, struggling to withstand the damp, clammy mist rising from the Liffey. He had not realized he had lengthened his stride until he heard the sounds of someone struggling to keep up.

“Mr. Burke?” She had one hand pressed to her side and a hitch in her gait. “I wonder if we might walk a bit more slowly.”

When she reached his side, he held out his free arm and she took it, not with the perfunctory brush of her fingertips, but with her whole hand, leaning heavily against him. Odd. She was petite, but she didn’t look frail. “Shall I hail a sedan chair, Miss Gorse?” Though truthfully, this was an unlikely spot to hail anything but trouble. And the more he thought of Mrs. Fitzhugh directing a woman to meet him here, in this fashion, the less he liked it. Why, he might have been detained at commons for hours, and she left alone as darkness fell…

Her touch lightened as she bristled. “I can walk.” Her step was almost brisk as they crossed the Carlisle Bridge. “So you’re in need of a governess?”

“For my sisters. Daphne and Bellis. Aged ten and eight, respectively. You’ll find them as ignorant as most girls their age, I daresay.”

She drew back her shoulders at that description. “Their previous governess was not firm enough with them?”

“I’m almost embarrassed to admit it, but they haven’t any previous governess. They are the youngest of the six of us and shockingly spoiled. My father in particular has always been prone to indulgence where they were concerned.”

Some emotion—he hesitated to call it disapproval—sketched acro. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved