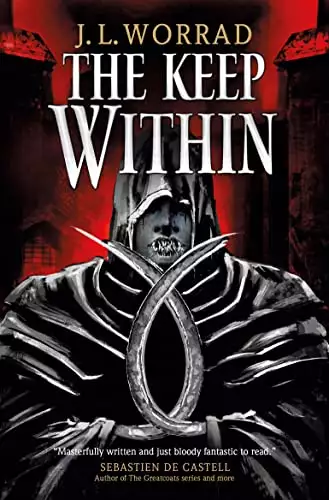

The Keep Within

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

When Sir Harrance ‘Harry’ Larksdale, bastard brother of the king, falls for a mysterious lad from the mountains, he is unwillingly caught up in a chaotic world of court intrigue and murderous folk tales. Meanwhile Queen Carmotta Il’Lunadella, First-Queen of the Brintland, needs to save her life and her unborn child. With the Third-Queen plotting against her, and rumours of coups rocking the court, Carmotta can rely only on her devious mind and venomous wit.

But deep within the walls of Becken Keep squats the keep-within – patient, timeless, and evil. To speak of the keep-within outside the walls of Becken Keep guarantees your bizarre and agonising demise within nine days. All the while, people fearfully whisper the name Red Marie: a bloodied demon with rusted nails for teeth and swinging scythes who preys on the innocent.

Harry and Carmotta are clinging to their dreams, their lives, by threads. And, beneath all, the keep-within awaits.

Release date: March 28, 2023

Publisher: Titan Books

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Keep Within

J. L. Worrad

Never seen such a beautiful hall,’ the lad said.

Never seen such a beautiful hall,’ the lad said.

‘It’s a roadside inn,’ Mother Fwych replied. ‘Uglier by daylight, inns.’

‘All things are,’ the lad Gethwen said, the fool, and his breath curled up into the night.

Miserable place. But Aifen-the-Tom had lost all lust for the mountains of his forebears and Mother Fwych refused to walk the miserable tracks of a flatland city. A roadside inn were the best place either might stoop to meet each other.

She looked at the flicker of the inn’s windows in the lad’s frost-blue eyes. The lad thinks this pile pretty.

The path to the inn were churned mud hardened by frost, cracking beneath heel and toe. Night sky naked above, her black skin twinkling. Yulenight soon, Mother Fwych thought. So little time left. So little.

Something flickered, a movement along the inn’s white wall.

She stopped. She squinted at where the movement had been. The roof hung lowest there, and the wall’s white paint mottled into moss. A shadowed place. Her eyes, and the powers Father Mountain had blessed her with, insisted upon it. A shadowed spot. There was nothing there that breathed or moved.

‘Mother Fwych,’ the lad whispered.

She ignored him, straining to see into the shadows, to see a flicker there as she had seen it before. She touched the hilt of her shortclaw.

No. Nothing. But her hackles were up. Something were wrong.

‘It’s naught, lad.’ She grinned at him. ‘Mother Fwych is getting old, she is.’ Sixty now. And the rest. How had that happened?

The lad were older too. Mountain’s love, but ‘lad’ were a dead word for him. Twenty summers? A man now, Gethwen, girlish-handsome, with the lip and brow rings of a man. But to Mother Fwych he were still that cursed boy they’d brought her.

‘Be warm inside,’ Gethwen said.

‘I’ll go first,’ she told him.

She turned the iron ring and opened the door inward. Hearth warmth greeted her, the sort that makes men tellers of tales. Yeast and pottage filled her nose, so too the sweat of flatlanders hemmed in like the pigs they kept. She’d no love for these places. None.

The chatter did not stop when she entered. Mother Fwych had never known that to happen. Inns fell silent when mountain folk entered, at least in Mother Fwych’s experience. Silence, then muttering, and then the words. One time they had even tried to scalp Mother Fwych, back when her hair were still red and mountain folks’ red hair fetched a price. She’d taken a scalp or two herself that night. Cask of cider too.

Ten men stood or sat around the room, a young woman behind the bar, and though every one of them glanced a moment, their talk never broke step.

‘Good evenin’,’ the young woman said, approaching. She wore a big daft dress that made her body look too big for her head. Or maybe her body had grown to that, years spent by hearth and spit.

‘My lady,’ said Gethwen, putting on flatland airs. Plainly it weren’t just an inn the boy had hoped to see. Devious boy.

‘Sir.’ The young woman curtsied. ‘I believe you’ve a friend who awaits you. No offence, but might I ask for your blades while you dally here? It is the custom, knives and ale being what they are.’

‘The other guests keep their knives,’ Mother Fwych said.

‘Knives for eating,’ the young woman replied.

‘Three have swords. Must be a stretch to their plate.’

‘Those are regulars,’ the woman said. ‘Please, my lady. I cannot let you—’

‘Fine,’ Mother Fwych said, pulling her bronze shortclaw from her belt. ‘If it keep you at ease.’

She passed the blade to the woman and Gethwen gave his own.

The inn-woman smiled. ‘I’d not seen scythe-swords until this night.’

‘Keep ’em safe,’ Mother Fwych told her. She had another shortclaw tied to her back under her coat, a smaller one in her boot. A mountain mother always kept at least one claw hidden.

‘Your friend is in the snug over yonder,’ the woman said, nodding toward a nook in the far corner. ‘I’ll bring you both some ale, eh?’ With that she grinned and left them, stopping only to let a ginger cat pass.

Aifen-the-Tom were sat in the snug like the woman said, sat on the right-side bench with arms stretched wide across the cracked wooden table, a cup of ale between them.

‘Mountain’s grace, Mother Fwych,’ he greeted her, his voice as cracked as the table and his grin sharper than a shortclaw. Aifen-the-Tom was scarcely younger than Mother Fwych and scant larger. His red beard and hair were wild as a valley forest but his pate was peak-bare. It would have gleamed in the lamplight if not for the black tattoo of a wildcat’s face upon it. ‘Sit, sit.’

‘Mountain?’ Mother Fwych said. ‘When last did you stand within a mountain’s shadow?’ She let Gethwen sit first, upon the bench facing the tattooed man. She sat down beside him and budged him up.

‘Within a mountain’s shadow?’ Aifen-the-Tom said. ‘Must have been younger than this one.’ He tapped Gethwen’s chin with his thumb then reached into his own shirt. He pulled out a necklace. An oval of grey stone hung upon it. ‘But we of the wandering sort all carry a piece of the Spines upon our hearts.’

‘I like that,’ Gethwen said, smiling.

‘We shan’t be staying long,’ Mother Fwych announced.

‘Have an ale at least,’ Aifen-the-Tom said.

Mother Fwych tutted and looked about. This snug offered some protection with its wooden sides, but it also hemmed them in. The wall to their left had no window, no escape. She squinted at the ceiling. A wooden square up there, directly above her. A closed hatch. Now that she did not like. She did not like floors above heads at the best of times. Doorways from floors above to heads below were outright treacherous.

‘Relax, woman,’ Aifen-the-Tom said.

‘Mother,’ she corrected him. She weren’t taken by this way he had, of delighting in others’ discomfort. Not a man in the Spine Mountains would dare as much, not with a mother.

He gave her a pitiful look. ‘You’re in no danger—’ He raised his eyebrows. ‘—Mother.’

‘Let’s be having it,’ Mother Fwych commanded him. ‘Then we’ll be gone.’

Aifen-the-Tom chuckled and reached to one side. He pulled up a small hessian bag and dropped it on the table with a clank.

‘Glad to be rid,’ he said.

‘A most shadowed thing,’ she agreed.

‘A pain in the arse, more like,’ he said. ‘Fleawater’s full of screaming and nonsense cuz of it. Our own “mother”, the dark woman, she’s been churning folks to madness. Was she who had word sent.’

‘So why are you here and not her?’ Mother Fwych asked. ‘And why come here so bloody alone?’

‘I’m headman at Fleawater, not her,’ he answered, waving to the inn-woman to bring more ale. ‘Folk gotta know I’m tough and keen, tougher than, like as not, the next ten men who follow.’ He looked at Gethwen. ‘That’s how it is being a man, boy.’

‘Fool,’ Mother Fwych snapped. ‘With a fool’s vanity.’ She snatched the bag and stood up. Her arm got a queer, numb feeling, like when you bang an elbow. It vanished soon enough. Full of shadow, she thought of the dull weight inside. She passed it to Gethwen.

The inn-woman came toward them, a kind smile on her face and three beers on a tray. Her smile vanished.

‘Now!’ she screeched and she threw the tray at the snug.

Cups smashed against the wall. The tray clattered on the table and Mother Fwych were showered with ale. Gethwen screamed. Her eyes met Aifen-the-Tom’s: he looked as stunned as she felt.

A spear’s tip drove down from above, flashed silver before Aifen’s face and punched into his belly. He stared silent at the pole before him. The spear twisted and pulled out.

Damned hatchway!

Mother Fwych seized the bloodied spear as it lunged for her throat. A face leered down from the open hatchway: a young man, grinning with the strain.

‘Fall!’ Mother Fwych said, using the tongue.

The man dropped the spear and threw himself out of the hatch and on to the table face-first, sending up a puddle of ale. Mother Fwych lifted the spear and rammed it into the man’s spine with all her might.

Her shoulder burst with pain. She yelled and looked. A feathered bolt had torn her furs, sliced her flesh and lodged into the snug. Mountain’s luck it had not hit square on.

She saw the inn-woman reloading a crossbow.

Mother Fwych pulled her smallclaw from her shoe. Four inch o’ bronze. She aimed for the inn-woman.

A man were charging at the snug. One of those ‘regulars’, sword up high, bearing down on Mother Fwych.

‘Hold!’ Mother Fwych tongued and the man froze and stumbled, his mouth wide with confusion, a look she knew well.

The smallclaw found his eye. He dropped upon the tiles and shrieked.

Folks were bolting for the door.

‘Table up,’ she told Gethwen.

They hauled at the table. The spearman’s body slid forward on to the floor beyond the snug. The pain in her shoulder wasn’t so bad now her blood was up. Be a beast soon after, though, she knew that much.

They got the table on its end, blocking off the snug.

‘Ban-hag!’ the man on the floor was screeching. ‘Cunt’s a ban-hag!’

‘You never mentioned a witch, Selly!’ another man yelled at the inn-woman.

‘Shut up!’ the inn-woman, Selly, barked. ‘Just keep mindful her words can take you. That way she’ll have no power.’

The lamps had gone out above and it was dark in the snug now, the only light coming from the space between the table’s edge and the ceiling. Everything stank of ale. Gethwen still had the bag. He were close to weeping.

‘Let me think,’ Mother Fwych told him.

Selly had looked bulky in her dress, Mother Fwych realised, because she’d chainmail beneath. Then there were the men with their swords. Regulars, my arse. Damned pennyblades, that’s what they were. Scum of all flatlands. Scalped mountain folk for coin. Child-killers and rapists and pissers-on-shrines.

She reached out and felt the room. Selly’s mind was too hard and focused to tongue-puppet. She must have tangled with mothers before.

Mother Fwych felt three men: one-eye on the floor and two others across the barroom. One-eye was too pained and anguished to listen, the other two had hardened their minds but lacked Selly’s flint. They’d lose focus soon enough and then Mother Fwych would have her way right enough. But the tongue worked best if they saw her eyes.

‘Lad,’ she said to Gethwen. ‘Tie that bag to your belt. On my say, climb for the hatch above.’ She slapped the table legs; he could use them to climb. Nimble, Gethwen. Quick wits too, though she’d never told him so.

‘Ban-hag,’ Selly the pennyblade called, ‘I’m an artist, banhag. I paint pretty pictures with my crossy here.’ With all Selly’s speechifying Fwych tried to feel out her mind but, Mountain’s balls, Selly kept focused. ‘You’re thinking of that hatch above, ain’t yer? Well there’s a yard’s space between the table edge and the ceiling and that’s plenty. I’ll stick you both like honeyed fucking pigs.’

‘Shut up!’ Mother Fwych yelled. ‘Or Mother’ll pounce and gut you!’

‘And we’ll all thank you for trying,’ Selly said. ‘Savage.’

‘You only scratched me just now, Selly. You missed.’

‘I was just playing,’ Selly said. ‘I like to bleed a bitch.’

Mother Fwych nodded for Gethwen to get back against the wall. She stepped over to Aifen-the-Tom’s corpse and slipped her arms under his armpits. He stank of sweat and ale and his forehead smacked her collar.

She looked over her shoulder at Gethwen.

‘Make for the hatch when I say.’ She thought a moment. ‘Run for the city, lad. The city. They won’t think o’ that. Seek out our folk.’

‘Ban-hag!’ Selly shouted beyond the table’s wall. ‘We just want the crown.’

‘The what?’ Fwych said, acting unaware. She looked at Gethwen again. ‘I’ll be right behind you.’

The lad nodded. He said nothing. She had expected him to plead, say he would never leave her to die, but no. Gethwen was eager to take the only chance he had. It stung Mother Fwych, that. But he was what he was. A tricky-man.

You’ve raised a survivor, she told herself. You’ve done that, at least.

‘We know you have it,’ Selly called. ‘Be happier for everyone if you came out. Hand it over and be on your way.’

‘If that were true you’d have robbed our man when he entered.’ Mother Fwych took a breath – wound be damned – and braced to lift Aifen-the-Tom, his beard scratching at the valley of her teats. ‘You’re getting coin to shut lips.’

‘Stop being daft,’ Selly said. She laughed. ‘I’ll even give you your swords back.’

‘I’ve plenty enough, thank you.’ She lifted Aifen-the-Tom’s body, ignored the pang in her shoulder. She leaned Aifen against the table and his head fell back, his eyes still shocked. A thought came. ‘Hey, Pennyblade!’

‘Yes, witch?’

‘Who’s it paying you?’

A pause. Then Selly said, ‘Interesting fucking story, that. But I ain’t—’

Mother Fwych heaved Aifen-the-Tom up.

‘Now,’ she barked.

A cracking sound and Aifen headbutted Mother Fwych, dark blood pouring from his mouth on to her hair and nose. Selly’s bolt had hit the back of his skull.

Behind her Gethwen clambered up, his boots pushing on the table’s legs and he was gone like a ferret out a burrow, long before Selly might reload.

Mother Fwych dropped Aifen-the-Tom. She reached into her furs and round to her back. Drew out her longest claw, a curved bronze length long as a hand and forearm.

The road brings me here. She had to keep their attention, stop them from chasing Gethwen down. Now she either died or became a living hearth-tale.

Selly’s crossbow would be loaded by now. The fear came to Fwych then. Of the pain. Of Father Mountain’s embrace. Mother Fwych placed her free palm against the upright table. She would scream and push it over. In that confusion she would tongue Selly’s mind and slay her, then the two men.

Well, this were it, then.

‘Ah-lee-lee-lee,’ a new voice said, neither man nor woman. ‘’Tis Red Marie!’

A silence followed in which only the one-eyed pennyblade moaned.

‘The fuck?’ one of the men said. Then he screeched, high as a hawk.

‘You know me, little Selly!’ the voice said. ‘Up from the river I come-come-come, a very wonder of the world!’

‘Please,’ Selly begged.

‘What? You think me a folk tale?’

The table flew sideways like a door on hinges. Mother Fwych was there for all to see but no one cared. One of the men leaned against the bar, clutching the red patch of his trousers where his bollocks had been and staring at where they now were: draped upon Selly’s still unloosed crossbow. Torn and matted and red.

Selly saw Mother Fwych and jolted. For a second Fwych thought she’d get a pair of bollocks in her ribcage. But Selly never loosed her bolt.

Mother Fwych nodded to Selly for truce. Selly ignored her, eyeing every shadow in the room. It only dawned on Mother Fwych then that the table had moved all by itself.

The shelf behind the bar collapsed, cups and tankards rattling. No hand had touched it.

‘Fuck this,’ the other man said, and he ran for the door.

Something flew through the air and hit the back of the man’s skull. His face mashed into the studded oak door. He dropped, leaving a blood flower upon wood and iron.

‘Don’t you want to playyy?’ the voice said, everywhere and nowhere, tinkling like a stream. ‘I put nails in babes’ mouths and sew them shut! I’m Red Marie! I make carnations of spines! Oh, I’m Red Marie!’

The thing that had flown at the man lay on the floor: a severed head. The head of the man whose eye Mother Fwych had taken.

Selly saw it too. She was shaking.

Shaking at that name, Mother Fwych thought.

‘Strength,’ Mother Fwych told Selly. Then to the room: ‘Show yourself, beast!’

The bollock-less man dropped to his knees and collapsed, empty of blood.

Footsteps padded across the room. Tittering.

Mountain protect me, Mother Fwych thought. ‘Show yourself!’

More tittering. Everywhere. It were the thing Mother Fwych had sensed outside earlier, she were sure. Impossible to see when still, too swift to be seen when moving.

‘Selly,’ the voice said, ‘remember the time I danced in your dreams?’Red Marie giggled. ‘You were so little, Selly.’

Selly was sobbing, clutching her crossbow like a doll.

‘Show yourself!’ Mother Fwych roared with the tongue. ‘Show!’But her power was spread too thin. She had nothing to look at. She swung her claw at nothing. Again and again.

‘Hello, Mother,’ the voice whispered in her ear.

Her jaw wrenched. It cracked. The softness inside quivered and tore. The world flashed white and tittered.

Never seen such a beautiful hall,’ the lad said.

‘It’s a roadside inn,’ Mother Fwych replied. ‘Uglier by daylight, inns.’

‘All things are,’ the lad Gethwen said, the fool, and his breath curled up into the night.

Miserable place. But Aifen-the-Tom had lost all lust for the mountains of his forebears and Mother Fwych refused to walk the miserable tracks of a flatland city. A roadside inn were the best place either might stoop to meet each other.

She looked at the flicker of the inn’s windows in the lad’s frost-blue eyes. The lad thinks this pile pretty.

The path to the inn were churned mud hardened by frost, cracking beneath heel and toe. Night sky naked above, her black skin twinkling. Yulenight soon, Mother Fwych thought. So little time left. So little.

Something flickered, a movement along the inn’s white wall.

She stopped. She squinted at where the movement had been. The roof hung lowest there, and the wall’s white paint mottled into moss. A shadowed place. Her eyes, and the powers Father Mountain had blessed her with, insisted upon it. A shadowed spot. There was nothing there that breathed or moved.

‘Mother Fwych,’ the lad whispered.

She ignored him, straining to see into the shadows, to see a flicker there as she had seen it before. She touched the hilt of her shortclaw.

No. Nothing. But her hackles were up. Something were wrong.

‘It’s naught, lad.’ She grinned at him. ‘Mother Fwych is getting old, she is.’ Sixty now. And the rest. How had that happened?

The lad were older too. Mountain’s love, but ‘lad’ were a dead word for him. Twenty summers? A man now, Gethwen, girlish-handsome, with the lip and brow rings of a man. But to Mother Fwych he were still that cursed boy they’d brought her.

‘Be warm inside,’ Gethwen said.

‘I’ll go first,’ she told him.

She turned the iron ring and opened the door inward. Hearth warmth greeted her, the sort that makes men tellers of tales. Yeast and pottage filled her nose, so too the sweat of flatlanders hemmed in like the pigs they kept. She’d no love for these places. None.

The chatter did not stop when she entered. Mother Fwych had never known that to happen. Inns fell silent when mountain folk entered, at least in Mother Fwych’s experience. Silence, then muttering, and then the words. One time they had even tried to scalp Mother Fwych, back when her hair were still red and mountain folks’ red hair fetched a price. She’d taken a scalp or two herself that night. Cask of cider too.

Ten men stood or sat around the room, a young woman behind the bar, and though every one of them glanced a moment, their talk never broke step.

‘Good evenin’,’ the young woman said, approaching. She wore a big daft dress that made her body look too big for her head. Or maybe her body had grown to that, years spent by hearth and spit.

‘My lady,’ said Gethwen, putting on flatland airs. Plainly it weren’t just an inn the boy had hoped to see. Devious boy.

‘Sir.’ The young woman curtsied. ‘I believe you’ve a friend who awaits you. No offence, but might I ask for your blades while you dally here? It is the custom, knives and ale being what they are.’

‘The other guests keep their knives,’ Mother Fwych said.

‘Knives for eating,’ the young woman replied.

‘Three have swords. Must be a stretch to their plate.’

‘Those are regulars,’ the woman said. ‘Please, my lady. I cannot let you—’

‘Fine,’ Mother Fwych said, pulling her bronze shortclaw from her belt. ‘If it keep you at ease.’

She passed the blade to the woman and Gethwen gave his own.

The inn-woman smiled. ‘I’d not seen scythe-swords until this night.’

‘Keep ’em safe,’ Mother Fwych told her. She had another shortclaw tied to her back under her coat, a smaller one in her boot. A mountain mother always kept at least one claw hidden.

‘Your friend is in the snug over yonder,’ the woman said, nodding toward a nook in the far corner. ‘I’ll bring you both some ale, eh?’ With that she grinned and left them, stopping only to let a ginger cat pass.

Aifen-the-Tom were sat in the snug like the woman said, sat on the right-side bench with arms stretched wide across the cracked wooden table, a cup of ale between them.

‘Mountain’s grace, Mother Fwych,’ he greeted her, his voice as cracked as the table and his grin sharper than a shortclaw. Aifen-the-Tom was scarcely younger than Mother Fwych and scant larger. His red beard and hair were wild as a valley forest but his pate was peak-bare. It would have gleamed in the lamplight if not for the black tattoo of a wildcat’s face upon it. ‘Sit, sit.’

‘Mountain?’ Mother Fwych said. ‘When last did you stand within a mountain’s shadow?’ She let Gethwen sit first, upon the bench facing the tattooed man. She sat down beside him and budged him up.

‘Within a mountain’s shadow?’ Aifen-the-Tom said. ‘Must have been younger than this one.’ He tapped Gethwen’s chin with his thumb then reached into his own shirt. He pulled out a necklace. An oval of grey stone hung upon it. ‘But we of the wandering sort all carry a piece of the Spines upon our hearts.’

‘I like that,’ Gethwen said, smiling.

‘We shan’t be staying long,’ Mother Fwych announced.

‘Have an ale at least,’ Aifen-the-Tom said.

Mother Fwych tutted and looked about. This snug offered some protection with its wooden sides, but it also hemmed them in. The wall to their left had no window, no escape. She squinted at the ceiling. A wooden square up there, directly above her. A closed hatch. Now that she did not like. She did not like floors above heads at the best of times. Doorways from floors above to heads below were outright treacherous.

‘Relax, woman,’ Aifen-the-Tom said.

‘Mother,’ she corrected him. She weren’t taken by this way he had, of delighting in others’ discomfort. Not a man in the Spine Mountains would dare as much, not with a mother.

He gave her a pitiful look. ‘You’re in no danger—’ He raised his eyebrows. ‘—Mother.’

‘Let’s be having it,’ Mother Fwych commanded him. ‘Then we’ll be gone.’

Aifen-the-Tom chuckled and reached to one side. He pulled up a small hessian bag and dropped it on the table with a clank.

‘Glad to be rid,’ he said.

‘A most shadowed thing,’ she agreed.

‘A pain in the arse, more like,’ he said. ‘Fleawater’s full of screaming and nonsense cuz of it. Our own “mother”, the dark woman, she’s been churning folks to madness. Was she who had word sent.’

‘So why are you here and not her?’ Mother Fwych asked. ‘And why come here so bloody alone?’

‘I’m headman at Fleawater, not her,’ he answered, waving to the inn-woman to bring more ale. ‘Folk gotta know I’m tough and keen, tougher than, like as not, the next ten men who follow.’ He looked at Gethwen. ‘That’s how it is being a man, boy.’

‘Fool,’ Mother Fwych snapped. ‘With a fool’s vanity.’ She snatched the bag and stood up. Her arm got a queer, numb feeling, like when you bang an elbow. It vanished soon enough. Full of shadow, she thought of the dull weight inside. She passed it to Gethwen.

The inn-woman came toward them, a kind smile on her face and three beers on a tray. Her smile vanished.

‘Now!’ she screeched and she threw the tray at the snug.

Cups smashed against the wall. The tray clattered on the table and Mother Fwych were showered with ale. Gethwen screamed. Her eyes met Aifen-the-Tom’s: he looked as stunned as she felt.

A spear’s tip drove down from above, flashed silver before Aifen’s face and punched into his belly. He stared silent at the pole before him. The spear twisted and pulled out.

Damned hatchway!

Mother Fwych seized the bloodied spear as it lunged for her throat. A face leered down from the open hatchway: a young man, grinning with the strain.

‘Fall!’ Mother Fwych said, using the tongue.

The man dropped the spear and threw himself out of the hatch and on to the table face-first, sending up a puddle of ale. Mother Fwych lifted the spear and rammed it into the man’s spine with all her might.

Her shoulder burst with pain. She yelled and looked. A feathered bolt had torn her furs, sliced her flesh and lodged into the snug. Mountain’s luck it had not hit square on.

She saw the inn-woman reloading a crossbow.

Mother Fwych pulled her smallclaw from her shoe. Four inch o’ bronze. She aimed for the inn-woman.

A man were charging at the snug. One of those ‘regulars’, sword up high, bearing down on Mother Fwych.

‘Hold!’ Mother Fwych tongued and the man froze and stumbled, his mouth wide with confusion, a look she knew well.

The smallclaw found his eye. He dropped upon the tiles and shrieked.

Folks were bolting for the door.

‘Table up,’ she told Gethwen.

They hauled at the table. The spearman’s body slid forward on to the floor beyond the snug. The pain in her shoulder wasn’t so bad now her blood was up. Be a beast soon after, though, she knew that much.

They got the table on its end, blocking off the snug.

‘Ban-hag!’ the man on the floor was screeching. ‘Cunt’s a ban-hag!’

‘You never mentioned a witch, Selly!’ another man yelled at the inn-woman.

‘Shut up!’ the inn-woman, Selly, barked. ‘Just keep mindful her words can take you. That way she’ll have no power.’

The lamps had gone out above and it was dark in the snug now, the only light coming from the space between the table’s edge and the ceiling. Everything stank of ale. Gethwen still had the bag. He were close to weeping.

‘Let me think,’ Mother Fwych told him.

Selly had looked bulky in her dress, Mother Fwych realised, because she’d chainmail beneath. Then there were the men with their swords. Regulars, my arse. Damned pennyblades, that’s what they were. Scum of all flatlands. Scalped mountain folk for coin. Child-killers and rapists and pissers-on-shrines.

She reached out and felt the room. Selly’s mind was too hard and focused to tongue-puppet. She must have tangled with mothers before.

Mother Fwych felt three men: one-eye on the floor and two others across the barroom. One-eye was too pained and anguished to listen, the other two had hardened their minds but lacked Selly’s flint. They’d lose focus soon enough and then Mother Fwych would have her way right enough. But the tongue worked best if they saw her eyes.

‘Lad,’ she said to Gethwen. ‘Tie that bag to your belt. On my say, climb for the hatch above.’ She slapped the table legs; he could use them to climb. Nimble, Gethwen. Quick wits too, though she’d never told him so.

‘Ban-hag,’ Selly the pennyblade called, ‘I’m an artist, banhag. I paint pretty pictures with my crossy here.’ With all Selly’s speechifying Fwych tried to feel out her mind but, Mountain’s balls, Selly kept focused. ‘You’re thinking of that hatch above, ain’t yer? Well there’s a yard’s space between the table edge and the ceiling and that’s plenty. I’ll stick you both like honeyed fucking pigs.’

‘Shut up!’ Mother Fwych yelled. ‘Or Mother’ll pounce and gut you!’

‘And we’ll all thank you for trying,’ Selly said. ‘Savage.’

‘You only scratched me just now, Selly. You missed.’

‘I was just playing,’ Selly said. ‘I like to bleed a bitch.’

Mother Fwych nodded for Gethwen to get back against the wall. She stepped over to Aifen-the-Tom’s corpse and slipped her arms under his armpits. He stank of sweat and ale and his forehead smacked her collar.

She looked over her shoulder at Gethwen.

‘Make for the hatch when I say.’ She thought a moment. ‘Run for the city, lad. The city. They won’t think o’ that. Seek out our folk.’

‘Ban-hag!’ Selly shouted beyond the table’s wall. ‘We just want the crown.’

‘The what?’ Fwych said, acting unaware. She looked at Gethwen again. ‘I’ll be right behind you.’

The lad nodded. He said nothing. She had expected him to plead, say he would never leave her to die, but no. Gethwen was eager to take the only chance he had. It stung Mother Fwych, that. But he was what he was. A tricky-man.

You’ve raised a survivor, she told herself. You’ve done that, at least.

‘We know you have it,’ Selly called. ‘Be happier for everyone if you came out. Hand it over and be on your way.’

‘If that were true you’d have robbed our man when he entered.’ Mother Fwych took a breath – wound be damned – and braced to lift Aifen-the-Tom, his beard scratching at the valley of her teats. ‘You’re getting coin to shut lips.’

‘Stop being daft,’ Selly said. She laughed. ‘I’ll even give you your swords back.’

‘I’ve plenty enough, thank you.’ She lifted Aifen-the-Tom’s body, ignored the pang in her shoulder. She leaned Aifen against the table and his head fell back, his eyes still shocked. A thought came. ‘Hey, Pennyblade!’

‘Yes, witch?’

‘Who’s it paying you?’

A pause. Then Selly said, ‘Interesting fucking story, that. But I ain’t—’

Mother Fwych heaved Aifen-the-Tom up.

‘Now,’ she barked.

A cracking sound and Aifen headbutted Mother Fwych, dark blood pouring from his mouth on to her hair and nose. Selly’s bolt had hit the back of his skull.

Behind her Gethwen clambered up, his boots pushing on the table’s legs and he was gone like a ferret out a burrow, long before Selly might reload.

Mother Fwych dropped Aifen-the-Tom. She reached into her furs and round to her back. Drew out her longest claw, a curved bronze length long as a hand and forearm.

The road brings me here. She had to keep their attention, stop them from chasing Gethwen down. Now she either died or became a living hearth-tale.

Selly’s crossbow would be loaded by now. The fear came to Fwych then. Of the pain. Of Father Mountain’s embrace. Mother Fwych placed her free palm against the upright table. She would scream and push it over. In that confusion she would tongue Selly’s mind and slay her, then the two men.

Well, this were it, then.

‘Ah-lee-lee-lee,’ a new voice said, neither man nor woman. ‘’Tis Red Marie!’

A silence followed in which only the one-eyed pennyblade moaned.

‘The fuck?’ one of the men said. Then he screeched, high as a hawk.

‘You know me, little Selly!’ the voice said. ‘Up from the river I come-come-come, a very wonder of the world!’

‘Please,’ Selly begged.

‘What? You think me a folk tale?’

The table flew sideways like a door on hinges. Mother Fwych was there for all to see but no one cared. One of the men leaned against the bar, clutching the red patch of his trousers where his bollocks had been and staring at where they now were: draped upon Selly’s still unloosed crossbow. Torn and matted and red.

Selly saw Mother Fwych and jolted. For a second Fwych thought she’d get a pair of bollocks in her ribcage. But Selly never loosed her bolt.

Mother Fwych nodded to Selly for truce. Selly ignored her, eyeing every shadow in the room. It only dawned on Mother Fwych then that the table had moved all by itself.

The shelf behind the bar collapsed, cups and tankards rattling. No hand had touched it.

‘Fuck this,’ the other man said, and he ran for the door.

Something flew through the air and hit the back of the man’s skull. His face mashed into the studded oak door. He dropped, leaving a blood flower upon wood and iron.

‘Don’t you want to playyy?’ the voice said, everywhere and nowhere, tinkling like a stream. ‘I put nails in babes’ mouths and sew them shut! I’m Red Marie! I make carnations of spines! Oh, I’m Red Marie!’

The thing that had flown at the man lay on the floor: a severed head. The head of the man whose eye Mother Fwych had taken.

Selly saw it too. She was shaking.

Shaking at that name, Mother Fwych thought.

‘Strength,’ Mother Fwych told Selly. Then to the room: ‘Show yourself, beast!’

The bollock-less man dropped to his knees and collapsed, empty of blood.

Footsteps padded across the room. Tittering.

Mountain protect me, Mother Fwych thought. ‘Show yourself!’

More tittering. Everywhere. It were the thing Mother Fwych had sensed outside earlier, she were sure. Impossible to see when still, too swift to be seen when moving.

‘Selly,’ the voice said, ‘remember the time I danced in your dreams?’Red Marie giggled. ‘You were so little, Selly.’

Selly was sobbing, clutching her crossbow like a doll.

‘Show yourself!’ Mother Fwych roared with the tongue. ‘Show!’But her power was spread too thin. She had nothing to look at. She swung her claw at nothing. Again and again.

‘Hello, Mother,’ the voice whispered in her ear.

Her jaw wrenched. It cracked. The softness inside quivered and tore. The world flashed white and tittered.

2 Larksdale

Sir Harry Larksdale had a drunk and weeping playwright to deal with. Drunken playwrights were common as sparrows, of course, and weepers hardly unknown, but a drunk andweeping playwright sitting high up on a stage rafter? It was really too-too much. Absolutely and utterly utter.

Well, Larksdale thought, alone upon the varnished stage of the open-air theatre, I do so like a challenge. Which was true, albeit long after it had ceased being a challenge and had become mere story.

‘Tichborne?’ Larksdale called up, his breath steaming in the December air. ‘You’ll find no inspiration up there. In fact, I’m told there’s but a pigeon’s nest.’ Larksdale stroked his beard with a gloved and many-ringed hand. He noted the birchwood ladder lying nearby upon the stage. He gestured at it. ‘Now that’s not clever is it, Tich-o, me-lad? You’ve gone and marooned yourself.’

A clay bottle smashed upon the boards. Quite empty, of course.

‘Piss your breeches, Larksdale,’ Tichborne barked. ‘You’re just the money! Grubby fingers in a silk purse!’

‘You wound me, sir,’ Larksdale said. ‘As only a mortal angel capable of golden verse can.’

‘Up your arse.’

He hasn’t finished our play for Yulenight Eve, Larksdale surmised. Worse, likely not even started. The symptoms were familiar enough: the vulgarity and nihilism, the disregard for flasks.

‘I’ll pass you the ladder,’ Larksdale said.

‘Don’t bother,’ Tichborne replied. ‘I’m soon to throw myself off.’

‘And what?’ Larksdale chuckled, stroked back a stray lock of black hair. ‘Break your ankles?’

‘Not if I dive head first.’

Then you’d likely bounce, fathead, thought Larksdale, but it was an uncharitable notion. The dear fellow was suffering, after all. Larksdale wasn’t eager to scale a rickety ladder, but he wasn’t eager to waste an hour shouting up at an inebriated quill-jockey either. Larksdale had an engagement – a royal engagement at Grand Gardens, no less – to attend at noon. It seemed the time had come for ol’ Harry Larksdale to become a man of action and valour, despite that being the very sort of man he crossed streets to avoid.

‘Tichborne,’ he called up, ‘I’m going to climb up beside you. Please don’t push the ladder away and send me to my death. I’d never say a nice word about you again.’

The playwright ignored him, staring at his own hanging feet.

‘Right,’ Larksdale muttered. He gazed at the ladder upon the floor as if it were a chore he’d been avoiding, which increasingly it was. ‘Right, then.’

The scuffle of boots upon wooden stairs came from stage left and Boathook Marla emerged. For such a slight woman she had an uncanny talent for stomping.

‘Boss,’ she said to Larksdale, ‘it’s all going to shit out there.’ She thumbed behind her, toward the backstage chambers.

‘Wonderful,’ Larksdale said. A thought struck him. ‘Wonderful that you’re here, I mean. Come, sweet Marla, and be my foundations, my rampart, my very rock.’

‘Hold this ladder up.’

She gestured behind her again, toward the wings. ‘But, boss—’

‘To each matter its time, Marla.’

She shrugged and went to pick up the ladder. Like many things in Tetchford borough, ‘Boathook’ Marla Dueng was a wonderful mass of contradictions: a woman who dressed like a dockhand; possessor of a nickname all spoke but none knew the provenance of; her features and complexion that of her Chombod father topped off with her mother’s far more local blonde hair, the ends of which curled and bristled out from beneath her red woollen hat. Exactly the sort of person who’d never be permitted in Becken Keep, of course. Which was precisely why Sir Harry Larksdale enjoyed her company, along with everybody else’s at the Wreath Theatre.

‘Your rump-part and rock’s ready,’ Marla said, her shoulder against the now raised ladder. She had been careful to place its end to one side of Tichborne up on his rafter. ‘Y’alright, me duck?’ she called up to him. Boathook Marla hailed from Hoxham city, which meant she referred to people as ducks from time to time. To each their own.

Tichborne made no reply.

‘He’s in the pit of self-recrimination,’ Larksdale explained to Marla. He began to climb.

The breeze got stronger as he ascended; sea winds from Becken Bay scraping over the theatre’s circular roofs and pulling at his long coat. If anyone but Boathook Marla were holding this ladder he might well have made his excuses. He soon reached the top and, if he hadn’t the courage to sit on the rafter and meet Tichborne eye-to-eye, he could certainly curl his left arm over its varnished oak and meet Tichborne eye-to-thigh.

‘Listen well, playwright,’ Larksdale said, ‘for I will mutter discreetly.’ He sighed. ‘I wish to spare you humiliation.’

Tichborne looked at him, his button nose wrinkling.

‘You’re not drunk,’ Larksdale said. He gave the young playwright a stare he normally saved for enemies and lovers. ‘So drop the damned act.’

Tichborne shuddered. ‘How’d you guess?’

‘It took me some time,’ Larksdale said. ‘I suspected a ruse by the third step on my climb and was adamant by the eighth. Your performance is too-too laboured, my boy. Furthermore, you’ve a love of history I’d overlooked till now.’

‘What?’

‘Kit Kimble pulled this very ruse twenty years past, bless his memory. I was nine years old then but even I heard tale of it. Yes, word reached even Becken Keep.’ He brushed hair out of his eyes. This breeze was a menace, really it was. ‘Kimble’s verypublic cataclysm atop a rafter earned him extra coin and extra time, both of which he spent down the Carnation inn with hearty aplomb.’

Tichborne gave a coy sort of look that almost rustled Larksdale’s heart. ‘A little of both would not go amiss,’ he said.

‘I’ve neither.’

‘You have money, Harry,’ Tichborne protested.

‘It’s all tied up in mustard right now,’ Larksdale admitted. ‘Figuratively, I mean. A merchant ship at sea. So best we clamber down and act like nothing happened, eh? If we’re seen up here we’ll both be forced to act the drunkard.’

‘Foul buggerers!’ A man’s voice boomed from somewhere in the corridors behind the stage.

‘Boss,’ Boathook Marla called up from below. ‘That other matter…’

‘Noted,’ Larksdale said. He looked up at Tichborne. ‘Come on, me Tich-o.’

‘I’m tired, Harry!’ Tichborne shouted.

The force of it made Larksdale clutch harder to the rafter. It seemed real pain hid behind the fakery of anguish. It shone in Tichborne’s eyes.

‘I cannot write another folk-play,’ he muttered, eyeing below to see if Marla might hear. ‘I cannot repeat the same bloody scenes, the same gang of saints and miracles, the same victories of Neyes the Child and japes of Dickie o’ the Green and villainies of Red Marie.’ He growled. ‘And if I have to write another scene where a sinner is jabbed in the arse with a poker—’

‘Oh, but the crowd simply roars at that,’ Larksdale said. He remembered to shut up. ‘Pray continue.’

‘And every line I write some miserable eye judges – some priest or Perfecti, some ghoul of the Church – and scratches out the slightest word that grasps for the sublime.’

Risky talk, this. Larksdale was happier for the fact they conversed alone and at altitude.

‘Tichborne, I’m aware a folk-play has its limitations, but you are a true talent. Try not to see the medium as a pair of manacles but more as a chessboard, having hard rules that—’

‘I haven’t written your next folk-play,’ Tichborne said. ‘I have written a keep-play.’ He laughed. Shook his head. ‘Isn’t that pathetic?’

‘Pathetic?’ Larksdale smiled sadly. Poor, sweet fellow. ‘Well… not in the sense you mean.’

Keep-plays were a world away from folk-plays and obscured by ramparts and walls. They were performed within Becken Keep, of course, and in nobles’ halls throughout the Brintland and beyond. Keep-plays were cut from the same material as ancient Mancanese drama, full of richly drawn characters and ethical dilemma, hubris and wrecked kings. They were not, convention held, for the common man’s consumption. Not slightly.

‘So you see,’ Tichborne said, ‘I really should throw myself off head first.’

Well, here was a moment. Larksdale was at a crossroads, faced with the sort of decision he’d hoped to make a year or more hence. He had not even mentally listed the allies he would need for that next vital step in his great plan, his life’s work, let alone marshalled them. Perhaps, Larksdale reasoned, God or providence pricks me on. ‘Listen to me, Jon Tichborne. You know of Sir Tibald Slyke, yes?’

‘He’s Master of Arts and Revels,’ Tichborne said, squinting, ‘up at the keep.’ Hope lit his features. ‘You are on good terms, you and he?’

‘Pilgrim’s mercy no,’ Larksdale replied, ‘he thinks me a dangerous fool.’ As Tichborne’s hope sank Larksdale pressed on. ‘And the only good thing I have to say for him is he shall retire soon. So rumour has it.’

Tichborne met Larksdale’s gaze. ‘Leaving you to…’ He gestured at Larksdale.

Larksdale gestured at himself. ‘Leaving me. A man with not a single clue as to how to write a keep-play.’

Tichborne chuckled gleefully. Below, Marla muttered in a way that was as much a performance as anything seen upon that stage.

‘It’s certain?’ Tichborne asked. ‘You have our king’s blessing?’

‘Am I not his brother?’ Larksdale said, avoiding the question.

‘One of a hundred bastards.’

‘The old king was prolific, granted,’ Larksdale said.

‘And his work of variable quality.’

Larksdale grinned. ‘I should push you off of here, Tichborne, really I should.’

The two men laughed. An ally is a fine thing, Larksdale told himself. It was as if a weight had been removed. He wanted to spill more, speak of his greater plan, the audacity of it. But he could tell none.

‘One more folk-play, eh, Jon?’ Larksdale said. ‘One more hot poker to a sinner’s rear. That’s all I beg.’

‘For you, Sir Harry,’ Tichborne declared, ‘I’ll sear every buttock in hell.’

Footfall and shouting burst on to the stage below. Larksdale’s boots slipped off the ladder’s rung and he fell. He gripped the ladder’s sides, slowing his descent, and was shocked to find his feet had landed safely upon the floor.

The hullabaloo had cut silent and everyone – some fifteen people or more, mostly the Wreath’s staff – were staring at him. Larksdale realised they all thought he’d purposefully meant to descend so rapidly. He didn’t disillusion them.

‘What ribald hell is this?’ he demanded of the crowd. ‘I’ll permit no drama here.’

Boathook Marla muttered to him, ‘Said it had all gone to shit, didn’t I?’

A burly, whiskered and well-dressed man glared at Larksdale. Two large men – identical twins with curly blonde hair – stood behind him, long-knives at their belts.

‘Well, well,’ the man spat, waving his walking cane at Larksdale. ‘Who is this hawk-nosed popinjay?’

‘Aquiline,’ Larksdale corrected him, pulling a splinter from his gloved palm. ‘The term is “aquiline”, or so Mother assures me. And who, sir, are you?’

‘A gentleman retrieving his property,’ the man said. ‘The name’s Cabbot. I assume you command this chamberpot of face paint and buggery?’

‘I’ve a controlling interest,’ Larksdale said.

‘Thief!’ Cabbot lifted his cane in the air, a fine thing of black lacquer topped with a brass figure. He pointed it at the gaggle of theatre hands. ‘That woman is my wife!’

A screech went up from the mob and the seamstresses of the costume department surrounded one of their number, a frail and sunken-eyed woman whom Cabbot glared at. Larksdale had never seen her before.

‘Seize her,’ Cabbot told his two lackeys.

The large twins looked at one another uncertainly.

‘Lazy sops,’ Cabbot told them. He raised his brass-topped cane. ‘I’ll bloody do it.’

Larksdale strode over and seized the cane from Cabbot.

‘Do not break the king’s peace, Cabbot,’ he told him. ‘For I am his brother.’

One could usually rely on that to quench a common man’s resolve. Not so Cabbot.

‘A bastard,’ he said. ‘I’m no peasant, sir. I’m landlord to half of Fleawater. I’ve friends up at your brother’s keep. I regularly play a few rounds of archery with Sir Tibald Slyke. We are to go into business. That name familiar?’ He looked Larksdale up and down with pointed disdain. ‘I respect a royal bastard but I’ll not be cowed. You’ve no land, no livery.’

‘But I’ve your cane.’ Larksdale wiggled the thing. ‘I note you’re not so forthright without it.’

Cabbot eyes were coals of rage. He was a big man, certainly wouldn’t need his guards to beat Larksdale to a pulp. But Cabbot didn’t know that. Most royal bastards were reared to be knightly killers, after all.

‘I want justice,’ Cabbot hissed as if releasing steam.

‘Then adhere to justice,’ Larksdale replied, ‘and don't threaten folk.’ He broke from Cabbot’s stare and looked to the man’s wife. She looked frailer and more frightened than ever. ‘She’s right to a divorce, should she wish it.’ The woman nodded. Larksdale looked back at Cabbot. ‘Should you accept payment.’

‘From you?’

Larksdale nodded. Please no, he thought. Please. It’s all on The Flagrant Bess with its hold of mustard powder. But he held his expression, trusted he had laid his trap. That he knew Cabbot’s type.

‘I’ll adhere to justice,’ Cabbot whispered with a grin. ‘Happily. Trial by combat.’ He looked over at his woman. ‘Husband and wife.’ He looked at Larksdale again. ‘You can’t buy me, bastard.’

Larksdale feigned slightest shock.

‘It’s the law, is it not?’ Cabbot said and then he laughed, whiskers shaking on his ruddy cheeks. ‘You were all for justice a moment ago.’

Larksdale shook his head. ‘So be it.’

‘I’ll break her and take her back home. As a husband should.’

‘And I’ll preside this trial and tourney,’ Larksdale said, ‘as is a royal bastard’s right.’ He looked for Boathook Marla so as to gesture to her to talk to Cabbot’s wife, whatever her name was, and was pleased to see Marla was already about the business.

‘Fine,’ Cabbot replied. ‘Pick your day, sir.’

‘How about now?’ Larksdale said. ‘How about here?’

‘Trial by combat occurs within a courtyard or field,’ Cabbot replied.

‘This stage has played those parts many times.’

‘What of witnesses?’

‘Good point,’ Larksdale said. He called out to Norton, the Wreath’s fool. ‘Go outside and tell ’em there’s a show, free to all.’

Norton slipped on his boar mask and, running over to the Wreath’s double doors and kicking them open, proceeded to cartwheel and declaim in the square outside.

‘Listen, you,’ Cabbot said, ‘I’ll be no mummer for the public’s folly.’

‘Fine,’ Larksdale said, ‘then I’ll pay for the divorce. A man like me can buy a man like you as he wishes.’

‘How dare you,’ Cabbot raged. He pulled off his coat and slung it at one of his identical bodyguards. ‘I’ve a house as big as this shithole! I’ve a permit to wear finery! I’m officially recognised as a gentleman!’

‘But you are not one,’ Larksdale said, shrugging. ‘Else why mention it?’

‘Give me my weapon, mollyboy!’ Cabbot demanded. ‘Let’s raise the deal too: I beat her and win, then I fight you. What say you to that?’

‘Whatever tickles your fancy.’ Larksdale turned to Cabbot’s two bodyguards. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...