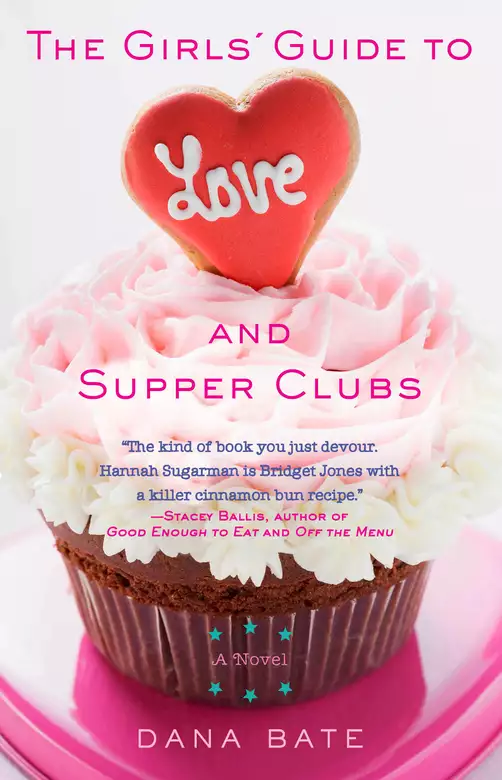

The Girls' Guide to Love and Supper Clubs

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Hannah Sugarman seems to have it all. She works for an influential think tank in Washington, DC, lives in a great apartment with her high-achieving boyfriend, and is poised for graduate school and an academic career just like her famous parents. The only problem is that Hannah doesn’t want any of it. What she wants is much simpler: to cook. When her relationship implodes, Hannah seizes the chance to do what she’s always loved and starts an underground supper club out of her new landlord’s townhouse.

Though wildly successful, her underground operation presents some problems. First, running an unlicensed restaurant out of someone’s home is not, technically speaking, legal. And she kind of forgets to tell her landlord—who just happens to be running for local office and wants to tighten neighborhood restaurant regulations—that she is using his place while he is out of town. On top of all this, Hannah is faced with various romantic prospects that leave her guessing and confused, parents who aren’t huge fans of cooking as a career, and her own fears and doubts that threaten her dreams. A charming, accessible romantic comedy, The Girls’ Guide to Love and Supper Clubs is a story about finding yourself, fulfilling your dreams, and falling in love along the way.

Release date: February 5, 2013

Publisher: Hachette Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Girls' Guide to Love and Supper Clubs

Dana Bate

I should have made something fancier, like chocolate mousse. Or a Sacher torte. Why didn’t I listen to Adam when he said bringing dessert was a silly idea? Probably because “silly” has become his favorite word to describe my obsessive interest in food, followed immediately by “crazy.” His criticism functions as muddled background music, like when my parents talk about my “future” and “direction.” The words barely register anymore.

Adam parks the car along the cobblestone circular driveway in front of his parents’ Georgetown home, a pale yellow mansion that takes up the better part of a city block. Among the Federalist brick and clapboard town houses, all sandwiched together along the tree-lined streets, the Prescotts’ stand-alone home towers above the rest, with its creamy facade, jet-black shutters, and series of rectangular columns covered by tumbling sprays of wisteria and knotted ivy. It is one of the most beautiful homes I have ever seen. It is also one of the most intimidating.

Adam smoothes his gelled, chestnut hair with his hands and shoots me a sideways glance as he unbuckles his seat belt. “You okay?”

“Fine,” I say. But of course I’m not okay. Everything about this evening lies outside my comfort zone, and I wish Adam would turn the car around and drive the two miles back to our apartment in Logan Circle, a neighborhood whose character is more vintage thrift shop than vineyard vines. But we’re here, and I have a carrot cake in my lap. Turning around is not an option.

I throw off my seat belt and steal a glance in the car’s side mirror. Disaster. I spent an hour and a half grooming myself, but thanks to the July heat and humidity, my forehead glistens with sweat, and my wavy locks have swollen into a fluffy orange mass. One more thing for the Prescotts to love: their son is dating Carrot Top. Carrot Top with the carrot cake. Perfect.

Adam fumbles for the door handle as I shudder at my reflection. “Relax,” he says. “There’s nothing to be nervous about.”

“I know.” But that isn’t true. There’s plenty to be nervous about, and we both know it. It’s no accident that, in the fifteen months we’ve been dating, this is the first time his parents have invited me to their home, despite the fact that we live in the same city. I would say “better late than never,” but at the moment, the idea of “never” seems just fine.

“Oh, but could you not mention the apartment?” Adam asks. “I still haven’t told them.”

“We’ve been living together for three months.”

Adam scratches his square jawline and looks through the front windshield. “I’m waiting for the right time.”

Whatever that means. We dated for six months before he finally introduced me to his parents. Then, too, he was waiting for the “right time.” At this rate, it will probably be November before he tells them we moved in together. If we’re still together then. The way Adam has been acting lately, I don’t know what to think.

I hop out of the car and follow Adam as he makes his way to the front door, scrambling to keep up as I balance the carrot cake on my arms. “You know I’m the worst at keeping secrets,” I say.

“It’s just for tonight. Please? For me?”

I sigh. “Yeah, okay, whatever.”

“Thank you. We don’t need a repeat of The Capital Grille.”

That’s where his parents took us for lunch the first time they met me, and suffice it to say, the lunch did not go as planned. They immediately sniffed out my lack of good breeding, which came to a head when I accidentally spilled a glass of Martin Prescott’s 1996 Château Lafite in his lap and proceeded to wipe the area around his crotch with my napkin, while uttering a few words and thoughts I probably should have kept to myself. By the time lunch was over, the Prescotts had made up their minds: I lacked the poise and refinement required of a future First Lady, which meant I was an unsuitable match for their son. I can’t say I blame them.

Balancing the carrot cake on one hand, I smooth my navy sundress with the other, checking to make sure everything is in its right place. The dress’s bulk adequately disguises my curvy figure without looking like a nun’s habit—a strategic move on my part, because although Adam may enjoy staring at my ample bosom, I guarantee his mother will not. Adam is dressed in his typical uniform: navy polo shirt, khaki pants, and penny loafers. A generous squirt of gel holds his dark brown hair in place, and his skin is a toasty butterscotch, thanks to a few summer weekends on the tennis court.

I follow Adam up the broad front steps, past the potted boxwoods and hydrangea bushes, and as we reach the top, the front door swings open.

“Adam!”

Sandy Prescott bursts onto the front steps like a little hurricane of pastels and pearls and frosted hair. She wraps her arms around Adam and kisses him on the cheek, squeezing his shoulders with her bony hands. Martin stands with one hand tucked into the pocket of his salmon-colored chinos and extends the other toward me. Between his boat shoes and Sandy’s pastels, I feel like I interrupted a photo shoot for the Brooks Brothers summer catalog.

“Hannah,” Martin says, grabbing my right hand. He squeezes until I lose feeling in my fingers, the sort of crippling grip one might expect from a high-profile Washington lobbyist. “Good to see you again.”

“Likewise.”

Sandy nods and flashes a quick smile as she glances at my chest, which, apparently, I haven’t disguised well enough. “Hello, Hannah.”

She drags her eyes up and down the length of my figure and makes a light, almost imperceptible clucking sound with her tongue when she spies my faux-leather sandals. Strike one. Two, actually, if you count my unfortunate anatomy.

Sandy tears her eyes from my feet and motions toward the doorway. “Shall we?”

Adam pulls me through the front door into the foyer, a room roughly the size of Alaska with about as much warmth. The ceiling rises fifteen feet, with a crystal chandelier that descends from the top and sparkles like a mini-solar system in the summer sun. A curved staircase sweeps up to the second floor and envelops a round, Louis Quinze table, which sits atop the sleek white marble floor. The entire house reeks of money, even more money than I realized Adam’s family had, and I see now why his parents bristle at my blatant disinterest in Washington society.

“What do we have here?” Sandy asks, pointing to the crinkly mound of aluminum foil perched on my arms. I tried to cover the cake without letting the foil touch the cream cheese frosting—a goal easier in theory than in practice—which means the cake now resembles a fifth-grade science project.

“Dessert,” I say, pausing before mentioning the inevitable. “A carrot cake.”

Sandy smiles tightly. “Carrot cake,” she says, taking the cake from my hands. “How fun.”

Adam sighs. “It’s one of Hannah’s specialties. Making it is at least a two-day project. Quite the ordeal.”

Sandy stares at the mountain of foil and knits her brows together as she shakes her head. “That sounds like an awful lot of trouble for something like a carrot cake. I guess I’ve always figured that’s what bakeries are for.”

She lets out a bemused sigh and carries the cake into the kitchen.

See? The carrot cake was a mistake. I knew it.

What follows is a carefully choreographed dance involving me on one side and the Prescotts on the other. I don’t want to step on the Prescotts’ toes, and they don’t want to step on mine, but really, all of us would be a lot happier if we didn’t have to dance at all. I, for one, would much rather sit along the sidelines and watch everyone else dance while I stuffed my face with candy.

But round and round we go, and the longer we dance, the more the smile tattooed on my face begins to ache and tingle and develop its own pulse. And yet I keep smiling, mostly because I am Adam’s girlfriend and they are his parents and, well, it’s pretty clear whose position is the least secure. I don’t expect the Prescotts to love me by the end of this dinner, but I would like, at the very least, for them to stop calling Adam every weekend to voice their concerns about our relationship while he hides in the bathroom and pretends I’m not sleeping ten feet away in our shared bed. In the scheme of things, I do not think this is an unreasonable goal.

We blow through a bottle of Veuve Clicquot as we nibble canapés on the Prescotts’ brick patio, and the champagne both calms my nerves and impairs my ability to focus on what, exactly, Adam and his parents are talking about. As our discussion progresses around the dinner table, I find myself drifting in and out of the conversation, as if the Prescotts are a TBS Sunday afternoon movie playing in the background while I fold my laundry and send e-mails. I hear what they are saying, and I am saying things in response, but significant periods of time pass where I’m not sure what is going on.

As I float away on my champagne wave, I lose myself in the thorny world of my own thoughts: how lately Adam seems mortified by everything I do, how moving in together has only magnified our differences and obscured our similarities, and how consequently I now feel as if I am in the wrong everything—the wrong job, the wrong relationship, possibly even the wrong city.

I snap out of my trance when someone mentions my name, though I’ll be damned if I can figure out who it was. But everyone is staring at me, so I think it’s safe to assume a question was involved.

“Sorry?”

“Your parents,” Martin says. “How are they?”

“They’re good. On sabbatical in London until October.”

“Wonderful,” Sandy says. She hands her empty soup bowl to Juanita, the Prescotts’ housekeeper. “Your parents do such interesting work.”

My parents are the only part of my pedigree of which the Prescotts approve. When Sandy heard my parents were Alan and Judy Sugarman, both esteemed economics professors at the University of Pennsylvania, she saw a glimmer of hope. I didn’t come from a wealthy or powerful family, but at least my parents carried the sort of academic heft that would look good in a New York Times wedding announcement.

“They aren’t the only ones doing interesting work,” Martin says. “Adam showed us the paper you coauthored on quantitative easing. Very impressive.”

“Thanks—although my boss was the one who wrote it. I only helped with the research.”

“She’s being modest,” Adam says, rubbing my shoulder. “You put a lot of work into that paper. And it showed. It was excellent.”

Martin smiles. “Looks like we have another Professor Sugarman in our midst, hmm?”

It is the question I dread most—and, I should add, the one I get asked all the time. Everyone assumes I aspire to be my parents someday, my every professional choice driven by a deep-seated desire to carry on their legacy. The way everyone poses the question suggests I should want that for myself—that I’d be crazy not to. And so what am I supposed to say when someone like Martin Prescott puts me on the spot? That I’d rather stab myself with a rusty knife than become a professor? That what I’d really like to do is start an offbeat catering company someday, but that my parents would go ballistic if I ever did? No, I can’t say those things, not when it’s clear that the one thing the Prescotts rate me for is a career I no longer care about and a scholarly legacy I want nothing to do with.

So instead I smile and simply say, “We’ll see.”

I grab for my wineglass and take a long sip and then, against my better judgment, I add, “But who knows. Maybe I’ll do something wild someday like start my own catering company.”

Sandy blanches. An obvious disappointment.

“Catering?” Martin chuckles, swirling his wineglass by its base. “Surely you can aim a little higher than that.”

Juanita returns to the dinner table, carrying three dinner plates on one arm and holding the forth in her opposite hand. She hands me the last of the plates, a gilded disk of porcelain filled with roasted potatoes, green beans, and some sort of meat.

“It’s slow-roasted leg of lamb,” Sandy says as I study my plate. She smiles. “I was planning to serve a pork roast, but I wasn’t sure if you would eat that.”

Ah, yes. The Jew ruins the party once again. The truth is, I love pork. I eat it all the time. But I can’t expect her to know that, and by her tone, it is clear that Jews are as foreign to her as aliens or cavemen.

I tuck into my portion of lamb, and the meat melts on my tongue, buttery and rich with red wine and the faintest hint of rosemary. “Wow, Sandy, what did you put in this? It’s fabulous.”

“Oh, I didn’t make this,” she says as she cuts her lamb into bite-size pieces and pushes most of it to the far corners of her plate, burying the meat under wedges of roasted potatoes.

Adam clears his throat. “Mom has a personal chef.”

“Oh,” I say. Of course she does.

“I’d love to cook,” she says, “but who has the time? I can’t afford to spend two days baking a cake.”

The implication, of course, is that only unimportant people have that kind of time. Unimportant people like me. I wait for Adam to jump in and save me, but instead he shoves a forkful of lamb into his mouth and feigns deep interest in the contents of his dinner plate. For someone with Adam’s political ambitions and penchant for friendly debate, I’m always amazed at the lengths he goes to avoid confrontation with his parents.

“I have a full-time job,” I say, offering Sandy a labored smile, “and somehow I manage.”

Sandy delicately places her fork on the table and interlaces her fingers. “I beg your pardon?”

My cheeks flush, and all the champagne and wine rush to my head at once. “All I’m saying is … we make time for the things we actually want to do. That’s all.”

Sandy purses her lips and sweeps her hair away from her face with the back of her hand. “Hannah, dear, I am very busy. I am on the board of three charities and am hosting two galas this year. It’s not a matter of wanting to cook. I simply have more important things to do.”

For a woman so different from my own mother—the frosted, well-groomed socialite to my mother’s mousy, rumpled academic—she and my mother share a remarkably similar view of the role of cooking in a modern woman’s life. For them, cooking is an irrelevant hobby, an amusement for women who lack the brains for more high-powered pursuits or the money to pay someone to perform such a humdrum chore. Sandy Prescott and my mother would agree on very little, but as women who have been liberated from the perfunctory task of cooking a nightly dinner, they would see eye to eye on my intense interest in the culinary arts.

Were I a stronger person, someone more in control of her faculties who has not drunk multiple glasses of champagne, I would probably let Sandy’s remark go without commenting any further. But I cannot be that person. At least not tonight. Not when Sandy is suggesting, as it seems everyone does, that cooking isn’t a priority worthy of a serious person’s time.

“You would make the time if you wanted to,” I say. “But obviously you don’t.”

Martin stabs a piece of lamb with his fork and shoves his glasses up the bridge of his nose. “Is this really appropriate, ladies?”

The correct answer, obviously, is no. Picking a fight with my boyfriend’s mother, a woman who already dislikes me, is not appropriate. It also is not wise. But by this point in the evening, I don’t care. I just want this dinner to end, and the sooner that happens the better.

Unfortunately dinner stretches on for an interminable two hours, giving me ample opportunity to take a minor misstep and turn it into a totally radioactive fuckup. And, knowing me, that’s exactly what I’ll do. Whether it’s muttering expletives while wiping Martin’s lap at The Capital Grille or railing against those who order chicken at a steakhouse—which Sandy ultimately did—I always manage to say exactly the wrong thing when the Prescotts are around.

Adam tries to play referee, jumping in with a story about his latest coup, an assignment to a Supreme Court case. He embellishes wildly, crediting himself with far more responsibility and power than he actually has, but Sandy and Martin eat up every word. They love it.

This is Adam at his best: the future politician, captivating the table with his charm and panache. From the moment I met Adam, I was, like any woman with a pulse, attracted to his chiseled features, his intelligence, and his ambition, but his charisma—that’s what sucked me in. That’s what hooked me. When Adam is “on,” being around him is electrifying, a total thrill of a ride you never want to end. He made me feel interesting. He made me feel alive. He took me to parties filled with political movers and shakers—White House Correspondents’ Dinner afterparties and charity galas and Harvard alumni events. He treated me like someone important—like someone who mattered. How could I not fall for someone like that? The man is magnetic, enchanting everyone he meets with his smiles and jokes and shiny white teeth.

All of which seems great until I realize tonight he is acting this way to shut me up.

Every time I attempt to join the conversation, Adam raises his voice and plows over me like a bulldozer, crushing me with his anecdotes and convivial banter. He kicks, squeezes, and prods me beneath the table, like I am an out-of-control five-year-old at a dinner party. I can’t get a word out, which, it becomes clear, is the point.

And that, I decide, is total bullshit. Adam used to love my spunk. That’s what he told me, anyway. I was nothing like the girls Sandy tried to fix him up with, girls who’d had debutante balls and regularly appeared in Capitol File magazine. Sure, I went to an Ivy League school, but in his Harvard-educated eyes, I “only” went to Cornell, which he considered a lesser Ivy. I grew up in a house the size of his parents’ foyer, wrote about financial regulation for a living, whipped up puff pastry from scratch. I was different, damn it. And that made me special. But tonight I do not feel special. Tonight I feel as I have on so many occasions recently: like part of a social experiment gone awry.

During a lull in Adam’s act, Juanita appears with my carrot cake, an eight-inch tower of spiced cake, caramelized pecan filling, cream cheese frosting, and toasted coconut. Miraculously, none of the frosting stuck to the foil—a small triumph. Juanita starts cutting into the cake, but I shoo her away and volunteer to serve the cake myself. If Adam wants to cut me out of the conversation, fine, but no one will cut me out of my culinary accolades.

I hand a fat slice to Sandy, whose eyes widen at the thick swirls of frosting and gobs of buttery pecan goo. I cannot tell whether she is ecstatic or terrified. Something tells me it’s the latter.

“My goodness,” she says. She lays the plate in front of her, takes a whiff, and then pushes it forward by four inches. I gather this is how she consumes dessert. “By the way, Hannah,” she says as I serve up the last piece of cake, “I read some very scary news last week about your neighborhood. Something about a rash of muggings?”

“Really? I hadn’t heard that.”

“You should be careful. Apparently Columbia Heights is still very much … shall we say, on the edge.”

“Oh, I don’t live in Columbia Heights anymore. Adam and I found a place together in Logan Circle about three months ago. We—”

I catch myself. Adam’s eyes widen in horror and fix on mine.

“I’m sorry, what?” Sandy says, her eyelids fluttering rapidly. “Did I hear you correctly? You two have been living together?”

Neither of us says anything.

Sandy’s voice grows tense. “Adam? Is this true? You’ve been living together—for three months?”

Adam clears his throat. “No. Yes. Let me explain…”

But before he can say anything more, Sandy clenches her jaw and shakes her head and leaps up from the table. Adam chases after her, and then Martin throws his napkin on the table and stomps out of the room after both of them, leaving me in the dining room, alone.

I stare at the mess of plates and napkins, scattered around the table amid the overturned forks and the slices of uneaten cake. The Prescotts haven’t touched my dessert, and given the hushed tones coming from the next room, they probably never will. I pull my plate closer, saw off a corner of carrot cake, and shovel a forkful into my mouth. The cake is delicious, the best I’ve made in months, bursting with the sweet flavor of cinnamon and carrots and the crunch of caramelized pecans and toasted coconut. It’s a masterpiece, and no one will ever know. I’m sure there are worse ways this evening could have gone, but at the moment, I’ll be damned if I can think of any of them.

Let’s be honest: the Prescotts were going to find out at some point. All I did was speed up the process.

And, really, with all of the champagne and red wine, combined with the prospect of sugary frosting and pecan goo, it almost wasn’t my fault. I was distracted. Who hasn’t made a few bad decisions under the spell of sugar and alcohol? Besides, Adam acted like a jerk for most of the evening. I’m hardly the only one at fault.

But something tells me none of these excuses will fly with my boyfriend, who has ignored me for the remainder of the evening. As he speeds toward the Q Street Bridge, I’m struck by how little he has said since we left his parents. The air-conditioning blasts through the vents in Adam’s Lexus, chilling the interior of the car as we move like a cool, hermetically sealed bubble through the thick, sticky summer air. Even at nine-thirty, the summer sky still holds a faint purple glow, draping the night in a dreamlike veil. Old-fashioned streetlamps dot the sidewalk, surrounded by leafy trees of varying sizes and blooming impatiens. The spires belonging to a series of Dupont Circle town houses loom on the horizon.

As we approach the bridge, Adam grips the wheel of his Lexus with two tense fists and presses down on the gas pedal. He races up behind a white Prius, a car moving at the speed limit, and rides its tail all the way across. When the opposing lane clears, he jerks the car over the double yellow line, speeds up, passes the Prius, and cuts back in front of it.

“Asshole,” he says as he gives the driver the finger.

I have no idea how driving the speed limit makes someone an asshole, and I am inclined to ask, but given Adam’s scarily aggressive tone, I decide not to bother.

Adam speeds up again as we cross Connecticut Avenue, flying through the very heart of Dupont Circle with its crowded streets and bustling sidewalks, and I clutch my seat and close my eyes, not at all comfortable with these hostile maneuvers, even though I recognize my earlier behavior is likely behind them. Regardless, I’d rather not die tonight.

But I will concede tonight was a disaster. An indisputable, excruciating disaster. Why do interactions with Adam’s parents always end this way? Because I’m me, that’s why. And Adam is Adam. I am chatty and unpredictable, and Adam is uptight and cautious, and when you throw us into a room with his parents, we somehow become exaggerated versions of ourselves, which is to say, polar opposites. I am the loose cannon, and Adam is the guy with a stick up his ass, and it is clear which kind of person the Prescotts prefer.

What Adam’s parents think of me shouldn’t matter, but it does—to both of us. Adam may have grown up surrounded by luxury and privilege, but we were both raised by parents who invested a significant proportion of their time and money into our upbringing and whose opinions always mattered—on the right schools, the right majors, the right careers and lifestyles. Why should their opinions about our significant others carry any less weight? I’ve always respected people who could flout their parents’ wishes on a regular basis and blaze their own trails in the face of their parents’ disapproval. But Adam and I aren’t like that. It’s one thing we’ve always had in common.

Adam turns onto the wider and less crowded thoroughfare of Fourteenth Street, and I decide to break the silence. “The carrot cake came out well.”

Carrot cake. That’s all I’ve got.

“Like it matters,” he mumbles under his breath.

“I’m sure they’ll get used to it. Us living together.”

Adam huffs as he races through a yellow light. “Don’t count on it.”

We don’t speak again until we reach the apartment.

Adam unlocks the door to our fifth-floor, loft-style apartment, which is located in the heart of Logan Circle. When I interned in Washington as a college student, Logan Circle was still considered “up-and-coming,” and I heard stories about the prostitutes who would loiter up and down Fourteenth Street. But over the past few years, dozens of shops and restaurants and galleries have moved into the area—everything from Whole Foods to the hip Cork Wine Bar and lowkey Logan Tavern—and now the Fourteenth Street corridor bustles with young professionals, who have moved into the area in droves. Our building sits on a lot where a run-down auto repair shop once stood, but now the decaying warehouse of beat-up cars has been replaced by eighty-four luxury rental apartments—none of which I could afford without Adam’s monthly financial contribution.

I follow Adam into the apartment, leaving a few feet between us as he storms into the living room. He throws his keys on the steel console, setting off a clang that echoes off the brushed cement floors.

“I can’t believe you told them,” he says as he throws himself onto our leather couch—his leather couch, actually, since I sold all my furniture before we moved in together, an idea that seemed to make sense at the time but now makes my stake in this apartment, this relationship, rather tenuous.

“I didn’t mean to,” I say. “It just sort of … slipped out.”

“Right. It slipped out. After I specifically asked you not to say anything.”

“I told you, I’ve never been good at keeping secrets.” Adam stares at me, unmoved. “At least they know the truth.”

Adam lets out a huff. “Yeah. Great.”

“They were going to find out eventually …”

Adam presses his palms against his temples and lets out a grunt. “You know what? I can’t deal with this right now. We’ll talk tomorrow.” He pushes himself off the couch and marches into the bathroom.

Okay, so he’s pissed. Or, more accurately, given the banging I hear going on in the bathroom, he’s flat-out angry. But if we have any shot at making this relationship work, his parents will have to accept and respect our decision to live together. We can’t live a lie forever. At least I can’t.

What worries me is I’m beginning to think Adam could. When I said Adam has never defied his parents, that’s not entirely true. He’s dating me, after all. That has been his one rebellion against them, his small act of resistance. But tonight, instead of charging forward in the face of their disapproval, he waved a little white flag and left me open to attack. And lately all the characteristics that drew him to my side—the way I was talkative and offbeat and sometimes a little weird—are pushing him away, as if I am a constant source of embarrassment.

He didn’t used to see me that way. When we first started dating, he introduced me to all his friends and colleagues as his little firecracker. That’s what he started calling me after our third date, when he brought me to a Redskins party at his friend Eric’s place. Eric had decided to make buffalo chili, but, in what became clear to both me and everyone else at the party, he had no idea what he was doing. Two hours into the party, after all of us had blown through the bags of tortilla chips and pretzels, Eric was still chopping red peppers. Determined not to let a room of fifteen people go hungry, I rolled up my sleeves, marched into the kitchen, and grabbed a knife. “Okay, Bobby Flay,” I said as I wielded my knife. “Time to get this show on the road.” I chopped and minced and crushed at rapid-fire speed, and in no time, dinner was served. “Get a load of this firecracker,” Eric said as he watched me work my magic. After that, the name sort of stuck.

For a while, the nickname seemed like a good thing. Every time I would rail against fad diets or champion the importance of sustainable agriculture or lament the lack of food options in inner cities, Adam would laugh and say, “That’s my little firecracker.” He made me feel special, as if I were a vital part of his life. His parents were the only people from whom he seemed to hide me, and though it bothered me a little, I understood. I was the anti-Sandy. That’s what made me attractive. But he hasn’t called me his little

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...