Introduction

BY LISA YASZEK

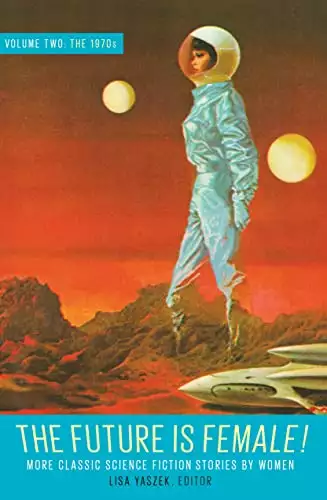

I am delighted to write this introduction in 2022, which marks the fiftieth anniversary of the slogan that gave name to this anthology. “The Future Is Female” entered the American vocabulary in 1972 when Jane Lurie and Marizel Rios began selling merchandise bearing those words to support New York City’s first feminist bookstore, Labyris Books. It was preserved for posterity when feminist photographer Liza Cowan took a picture of her girlfriend Alix Dobkin wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan for her 1975 slide show, “What the Well-Dressed Dyke Will Wear in the Future.” Cowan remembers that the phrase first caught her imagination because it had “no precise meaning. We are asked to absorb two powerful archetypes, and to imagine them in relationship to each other. . . . [It is] a call to arms. . . . And an invocation. . . . A spell for the good of all.”1 I would argue that these two archetypes have fueled feminism for nearly 250 years, and that they are both very much at the heart of the classic 1970s science fiction stories you will encounter in this anthology.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that there are as many definitions of “feminism” and “science fiction” as there are people who identify as feminists and science fiction enthusiasts—in fact, that is part of what makes both of these communities attractive to many people. However, by 1981, science fiction author Joanna Russ could easily identify scores of women writing a specific kind of future-oriented fiction that celebrated female agency, community, and sexuality in reaction to “what [its] authors believe society . . . and/or women lack in the here and now.” For Russ, feminist science fiction authors were—much like their political counterparts—bound together by a shared set of goals, using their art to demonstrate the limits of patriarchal culture and articulate the possibility of more egalitarian alternatives for all.

Of course, the idea that women might use science fiction to comment on the relations of science and society and to stake claims for women in the future was nothing new. Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World (1666) cast its author as a dimension-traveling philosopher-warrior queen who saves her homeland with an army of sentient alien animals. Meanwhile, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) dramatized the dangers of a male-centered science that excludes female intellect and morality, all while introducing modern audiences to some of science fiction’s most enduring characters, including the mad scientist, the scientist’s imperiled love-interest, and the misunderstood monster. At the turn of the twentieth century, feminists Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Pauline Hopkins, and Rokheya Sakhawat Hossain imagined techno-utopian futures in which women could become fully modern political and scientific subjects. Early and mid-twentieth-century science fiction writers like Leslie F. Stone, C. L. Moore, and Judith Merril helped build the genre by setting stories in living rooms and launchpads alike while exploring how science and technology might be deployed to literally reshape sex relations.

Then, on or about 1970, women’s science fiction changed— the date is approximate, but the evidence throughout the decade is palpable. This was not principally a matter of increased numbers; women had long comprised about 15 percent of science fiction professionals and while there were more women than ever writing in the 1970s, there were more men doing so as well, leading veteran author and agent Virginia Kidd to conclude that “the proportion of women writing . . . science fiction today may be exactly the same or, just possibly, a little bit larger” than in previous generations. Suddenly, however, women were much more visible in the genre. Women writers earned accolades from fans and professionals alike, taking home a disproportionate share of Hugo and Nebula Awards over the course of the decade (19 percent and 25 percent, respectively) while leading professional organizations such as the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA, recently renamed the Science Fiction Writers Association), the Clarion West Writers Workshop, and the Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association (SFPA). Women also made their mark as science fiction artists during this era. To offer just a few examples: Wendy Pini and Fara Shimbo (née Valenza) imagined futures populated by space-faring animals and females of all species for Galaxy (see figs. 1, 2); the Hugo and Caldecott award-winning wife-and-husband team Diane and Leo Dillon produced cover art for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction that staked claims for people of color in the future (see fig. 3); and Jeanne Gomoll helped lead the charge to create cons, fanzines, and even an amateur press association (APA) within feminist fandom (see Gomoll’s artwork for Janus, fig. 4). Perhaps most important, no matter what corner of the genre they hailed from, for the first time ever women began to represent themselves as a politically and aesthetically coherent group, creating a new mode of speculative art that would soon be known as feminist science fiction.

Like other forms of progressive politics, feminism enjoyed a resurgence in the 1960s and ’70s. Activists associated with new political groups such as the National Organization for Women (NOW) carried on the work of their suffragist foremothers by lobbying for equal access to employment and economic opportunities, while artists and scholars transformed Americans’ understanding of the past by recovering the herstory of strong-willed women who made their own present possible. Recognizing that “the personal is political,” activists created grassroots groups dedicated to women’s physical, mental, and sexual health issues and used new household technologies to redistribute domestic labor more equitably. As these latter examples suggest, science and technology were increasingly part of the feminist agenda in this historical moment. Social scientist Bernice Sandler led the legal battle that resulted in the Education Amendment Acts of 1972, which banned sex discrimination in all federally funded education programs; writers Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes launched Ms.magazine, also in 1972, to amplify feminist voices in the U.S. media landscape; and cultural theorist Shulamith Firestone argued that women should use new fertility technologies to seize “control of reproduction” and redistribute childbearing and childrearing practices.

At the same time, the science fiction genre at large was changing in ways that made it more relevant than ever to politically engaged artists. Blockbuster movies such as Star Wars(1977) and Star Trek (1979) and TV shows such as Battlestar Galactica (1978–79) and The Six Million Dollar Man (1973–78) proved that science fiction had moved from the margins to the center of American popular culture, as did the use of science fiction motifs in the music and performances of rock stars Jimi Hendrix, Paul Kantner and Grace Slick of Jefferson Starship, and George Clinton of Parliament. Science fiction invaded the mainstream world of words as novels by Michael Crichton and Anne McCaffrey topped the New York Times Best Seller lists and literary authors Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, and Margaret Atwood borrowed elements of the genre in their critically acclaimed fiction. Even scholars got in on the action, establishing the first professional organizations, journals, and conferences dedicated to the serious study of science fiction across media.

While the literary establishment began to visit the strange new world of science fiction, a “New Wave” of authors and editors returned to the genre with elevated aesthetic expectations. Coined by P. Schuyler Miller in 1961 to describe the group of science fiction writers associated with the British publication New Worlds under the editorship of Michael Moorcock, the phrase was soon extended to include United States writers such as Harlan Ellison, Roger Zelazny, Samuel R. Delany, Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert Silverberg, and Thomas Disch. Diverse in tone and theme, New Wave authors were loosely bound together by a shared refusal of the naive techno-optimism characteristic of earlier American science fiction. Instead, they innovated both stylistically and thematically, borrowing social insights from the soft sciences to explore the impact of technology on the human psyche, map the limits of a “rapacious industrial culture,” and speculate about the new science and societies that might replace our current ones. Although magazines remained important venues for publication, authors of experimental science fiction usually placed their most groundbreaking work in the original anthology series that were quickly replacing magazines as the center of generic innovation due to their “high pay, perceived prestige, and selectivity.” Over the course of the decade, authors and editors associated with anthology series, including Damon Knight’s Orbit (1965–80), Robert Silverberg’s New Dimensions (1971–81), Terry Carr’s Universe (1971–87), and Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions (1968 and 1972), earned a “remarkable number of Hugo and Nebula” nominations and wins.

Feminist science fiction author and editor Pamela Sargent recalls that the “atmosphere of change” heralded by the New Wave attracted women to the genre because it suddenly seemed that their stories “were likely to find a more receptive audience, even if [they] violated some of the traditional canons.” These women, many of whom are featured in the present anthology, included old pros who had been involved in science fiction for decades, such as Miriam Allen deFord and Elinor Busby; rising stars associated with the New Wave experiments of the 1960s, including Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Kate Wilhelm; and new authors who came to science fiction in the 1970s, such as Joan D. Vinge, Vonda N. McIntyre, Connie Willis, and Lisa Tuttle. Like their activist counterparts in the Women’s Liberation Movement (and, for that matter, like their male counterparts in the science fiction community), the majority of feminist science fiction authors publishing in the 1970s identified as white, middle-class, heterosexual, and cisgender. Not surprisingly, many of their stories revolve around characters with similar identities and values. But, as in the larger feminist community, women science fiction writers of this era were indeed taking the first tentative steps toward exploring how sexuality and race might complicate some of America’s most-dearly held beliefs about “Woman” as a universal, biologically-based category that encompasses the experience of all people who identify as female or femme.

The nascent feminist science fiction community was home to LGBTQ+ authors Joanna Russ, Vonda N. McIntyre, Alice Sheldon, and C. J. Cherryh, all of whom wrote stories exploring same-sex love and desire, as well as straight-identified authors such as Marta Randall and Kate Wilhelm, who imagined futures where homosexuality is an unremarkable part of everyday life. It was also home to pioneering BIPOC authors Joan D. Vinge, Marta Randall, and Octavia E. Butler (whose work is featured in a separate Library of America volume, Octavia E. Butler: Kindred, Fledgling, Collected Stories). From the start, Butler grappled with issues of race and racism in science fiction more directly than most of her counterparts, noting that the genre “has always been nearly all white, just as, until recently, it has been nearly all male” and that “science fiction, more than any other genre, deals with change. . . . But science fiction itself changes slowly, often under protest.” (“Lost Races in Science Fiction”). Still, Butler was not entirely alone: at least a few other feminist authors of this era, including Randall and white-identified writers such as Miriam Allen deFord, took up Butler’s challenge to “spread the burden” of representation in science fiction by casting women of color as their protagonists. Taken together, such authors paved the way for the rich and still-growing body of modern, intersectional feminist science fiction we enjoy today.

Like their male counterparts, feminist science fiction writers were often drawn to genre fiction by the vast canvas it provided for their imaginations. As Eleanor Arnason puts it, “I’ve always read science fiction and fantasy and murder mysteries. . . . My problem with realism is that a realistic novel about the psychological problems of middle-class people is a story which is very similar to the life I’m leading, and thus is not too interesting. Whereas the minute you throw in a dragon or global warming, it becomes very interesting. Internal thoughts become much less important, and you basically want to deal with the dragon.” For others, science fiction provided an escape from midcentury America’s many constraints. Marta Randall turned to it for reassurance that “I wasn’t going to be the one stuck at home baking cookies, I was going to be the one balancing on the raft in the lashing seas, gripping the mast with one hand while the other held on to the cookies somebody else had baked.” Still others embraced science fiction as teens and young adults because it promised, as Sargent puts it, “that just about everything could be other than it is.”

Several of the women you will encounter in this anthology directly attribute their careers to reading science fiction at a young age. Connie Willis recalls that Robert Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit—Will Travel showed her the genre could be both “very literary and very funny,” while Judith Merril’s Best of SFanthologies revealed the “vast variety of things you could do” with the genre. Upon reading Frank Herbert’s politically and environmentally engaged Dune, Cynthia Felice realized that “this is the kind of thing I write!” Other women writers were inspired by science fiction television, radio, and film. Eleanor Arnason was “hooked” after seeing her very first episode of Captain Video, and C. J. Cherryh credits Flash Gordon as direct inspiration for her career. “When that went off the air, after about 5 complete runs, I had to write my own episodes,” Cherryh recollects, “but I was so afraid of the plagiarism police (thank my 5th grade teacher) that I changed every fact and character to something opposite. And ended up with an original.”

Many of the women associated with the founding of feminist science fiction were themselves from families of remarkable women. During the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, Gayle Netzer’s great-grandmother Adeline Foot single-handedly defended two families from a Dakota attack after the men with them were wounded; according to Foot’s husband, white people never acknowledged her heroism but the Dakota honored her with the name “Brave Woman Who Defended Her House with Her Gun.” Miriam Allen deFord’s dual career in socialist journalism and science fiction was inspired by her experiences with collective activism as a teenaged “soapbox suffragist.”Eleanor Arnason, niece to Molly Yard, Eleanor Roosevelt’s personal assistant and the eighth president of NOW, attributes her interest in science fiction to growing up in an experimentally designed home surrounded by artists and activists, noting that “avant-gardists, like socialists, believe in the future.”These authors were often active in the revival of feminism and other progressive politics themselves: Netzer participated in the 1977 National Women’s Conference; deFord was the subject of an oral history project called “The Suffragists: From Tea-Parties to Prison”; and Arnason, “coming from second-wave feminism,” has worked for striking coal miners in Kentucky, served as an official in the National Writers Union, and engaged in Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party politics.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved