- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

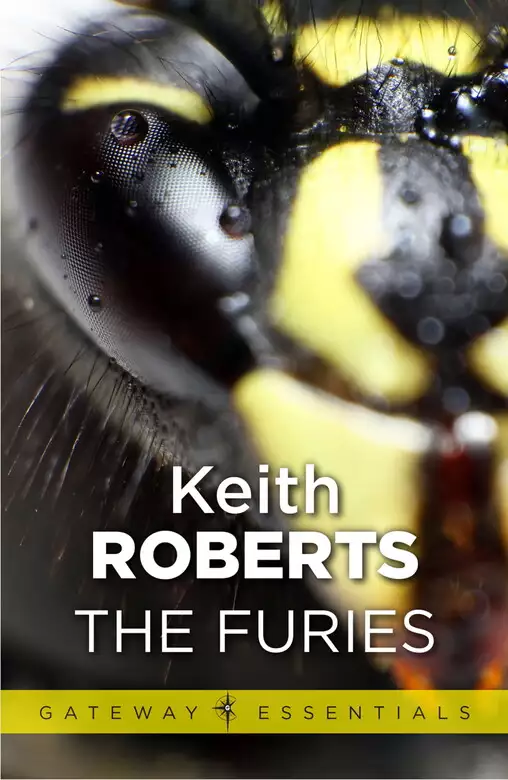

America and Russian both explode huge H-bombs simultaneously. The tests go wrong, cracking the seabed, rupturing continents and engulfing cities. The Thames flattens into a flood plain, London is drowned. Now comes cosmic retribution - giant wasps, monstrous and deadly, directed by a supernatural intelligence, invade a reeling world. In England, isolated guerrillas fight on¿

Release date: September 29, 2011

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 220

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Furies

Keith Roberts

Maybe the Keepers were tired. To them, Vanderdecken was an ephemeral creature and the millennia of Ahasueras no more than the slow blinking of an eye. Their voyage stretched for ever, into the future and into the past, back, back, back beyond our Time, back maybe to the Prime Creation. Where they had come from, even the Keepers had forgotten. How they had been spawned they had never known.

They could not bleed, they could feel no pain or fear. They owned no cells that could die, no bone that Time could vaporize. They were raw, and nude beyond our comprehension of bareness. Maybe at last they had become hungry. Hungry for the thick comfort of flesh …

It could be they found us by blind chance; or perhaps they sensed us and were drawn. Maybe the fears of terror-stricken worlds spread like ripples into unguessable continuums, bringing their own retribution. We shall never know. What we do know is that the space-things discovered Earth. They saw the warmth of her sun. They tasted the green of her continents, the blue-silver skeins of her seas. They sensed her Life with every ramshackle nerve, and to them all that they found seemed good. They piloted their burden through meteor-haunted shells of air. They dropped down to where they could see cities boiling like the homes of insects. Then lower, and closer, and lower … They hung in the sky, invisible, a focus of storms and anxieties. They watched and schemed and planned and observed; and in time, their choice was made.

They turned on the thing they had protected for so long, ripping it apart, gobbling its essence into themselves. They swelled with new knowledge and confidence. They readied themselves for their first and only transformation; and somehow, somewhere, the incredible happened. The Word – their Word – became flesh …

I’VE SHOWN that opening to three or four people and so far nobody has liked it. They say it’s too fancy and in any case it can’t be proved. I know it can’t be proved, and as for being fancy; well, this is my book and I reckon I can start it any way I want. After all, I was asked to write it; I pointed out at the time I was a cartoonist not an author, but nobody would listen.

I’m Bill Sampson, and as I said I used to draw funny faces for a living. The year all this started, the year of the Neptune Test, I was living in a village in Wiltshire called Brockledean. I suppose I’d done pretty well for myself; I’d got my own house, an XK150, and a Great Dane, I was fairly comfortably off and I wasn’t quite thirty. I’d had a stroke of luck of course; I’d done a lot of jobs in my time, from driving lorries to hauling boxes about in a department store, nothing had lasted very long and I’d never made more than a bare living, sometimes not even that. Then I ran into an old contact of mine and managed to weasel my way into a freelance arrangement with one of the big publishing houses just as they were launching a new kids’ comic. I was working as a general hack in a seedy little agency at the time; I chucked that when I got a bit more established, and not long afterwards I was worth enough to be looking round for some nice fat chargeable expenses to fool the tax people. A pal of mine suggested I put some money into property. It seemed a good idea; in those days even a lousy businessman could scarcely lose with bricks and mortar. I started looking around.

The choice wasn’t easy. I’d sworn I’d never live in a new house; there was something about modern jerry-building that I found infinitely depressing. A Development affected me like a blowsy London pub, it reminded me of the shortness of life. I saw a lot of property; most of it was in the active process of falling down, and the prices conformed to my definition of daylight robbery. Then I heard about the place at Brockledean and drove out to have a look. It seemed ideal. The house had been a pub at one time, and it stood on its own about a mile away from the main village. Not much in sight except a handful of farm outbuildings. The countryside round about wasn’t exactly beautiful, but it was undeniably pleasant. There was a room with a north light that would be fine for a studio, and there was a garage. The garden was small and mostly under grass, so keeping it in order wasn’t going to be a full-time job. All in all the set-up just about fitted my needs; I got a mortgage without too much trouble and settled down to enjoy a life of rural simplicity.

I developed a routine. Once a week I’d go to London to deliver artwork and collect scripts, the rest of the time including Saturdays I’d work like a bank clerk. There’s nothing romantic about art of course, it’s just like any other job. You work fixed hours and try to put it out of your mind when you’re off duty; sit round waiting for inspiration and you’d soon run out of crusts. My days were pretty full at first because I was catering for myself; cooking the evening meal usually turned out to be something in the nature of a crisis. I got better in time of course, though I’ll admit I’d never make a chef. After the smoke had cleared and I’d washed the dishes I’d usually prowl round the house for a while just trying to picture what it had been like in the good old days when it was a pub. That wasn’t difficult; it was the sort of place that invited imaginings. The main structure wasn’t old as country houses go, but the foundations and cellars were a different thing altogether. The floors were massive, supported by heavy beams, and downstairs there were some round brick arches that looked to me like sixteenth-century work at least. There’d been a tavern here in the times when the loving-cups were passed. Perhaps the place was haunted; there were all sorts of pleasant possibilities.

As you’ve probably worked out I’m a bit of a melancholic by nature. I love old things; old buildings, old ideas. The house still kept a lot of relics of its pub days; there was a mark on the brickwork of the front wall where a notice of some sort had been fixed, and there was a post that had evidently supported a sign. It was bare now and stuck up beside the gate like a little gibbet. The estate agent was going to have it removed but I wouldn’t hear of it.

I settled down quickly enough, but after a few months I got to feeling that something was missing somewhere. I’d lie awake nights and listen to the timbers settling and creaking, and the hundred unidentifiable noises that old houses make, and I’d feel pretty lonely. I’d promised myself I’d never have a woman in the place; I hadn’t been able to find anybody to share the hard times, not that I blamed them, and now I was better off I was too crabby to want to split my profits with a wife even supposing I could find one. If I needed company though there was an obvious alternative; I bought myself the Great Dane.

She was a bitch; I’d wanted a dog, but when I saw her sprawling round the run at the kennels I knew I was just going to have to buy her. She was black, like polished jet, and from the time she was a knobbly-kneed puppy there was only one name for her. Sekhmet, Egyptian goddess of darkness, consort of the lord of the underworld. Maybe it was a little high-flown; anyway it soon got shortened to Sek, which was classically unsound but a whole lot easier to yell.

One of Sek’s minor advantages was that she seemed inordinately fond of my cooking. I could never resist the temptation to dabble about with fancy recipes; as often as not the results were disastrous, but it seemed to me the more horrible the mess the more she enjoyed it. Maybe she was just being tactful; it was hard to tell with her, she was naturally polite.

When the daily battle was over I usually walked Sek for a couple of miles. We’d always finish up at the Basketmaker’s Arms in Brockledean. She was a firm favourite there. They kept biscuits behind the bar for her; she’d stretch her neck, push her great dark head over the counter, roll her lips back from her teeth, and take the goodies as if they were made of glass. Then she’d eat them without leaving a crumb. She developed a fair taste for beer as well, though I usually restricted her to a dishful at the most. I felt one dipso in the family was enough.

They were a nice crowd in the Arms, farm workers, market gardeners, an old Diddy who ran a one-man scrap business; the type of folk I like. I had one particular friend there. His name was Tod; he was a great character, and as Irish as they come. He was a County Mayo man, an agricultural graduate and a ‘grower’. His people had been growers for generations, and although he was a company director, he’d never got round to thinking of himself as someone different. He used to travel the country advising on problems to do with agriculture; his firm specialized in crop spraying and he was an expert on pest control. I did one or two little jobs for him from time to time, copywriting, layouts and visuals for advertising, that sort of thing. I’d never take any money for them, but Tod paid in kind; and they had a sort of exhibition spread just down the road and he was my source of supply for fresh eggs, farm butter and cheese, and the Lord knew what else besides.

It was from Tod that I first heard about the Furies. I walked into the Arms one night in late June when Sek was eighteen months old and just coming into her prime. Trade was slack, but Tod was sitting in his usual place at the far end of the bar, nose in the Daily Echo. He handed the paper across to me, marking an item with his thumb. By sheer luck I’ve managed to get hold of a copy of that article; it was headed ‘Strange attack in Dorset’, and it ran as follows.

FROM A SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT

News was received today of an odd incident involving a man from Powerstock near Bridport, in Dorset. James Langham, a farmhand, was driving a tractor on the property of his employer, Mr Noel Paddington, when he was attacked by what he described as a monstrous wasp. The creature, said by Langham to have been a yard or more across the wings, appeared suddenly over a hedge and dived at the machine at great speed. Langham was able to duck out of the way of the assault, the insect passing over his head and hitting the wheel of the tractor. The assailant then fell to the ground, enabling Langham to kill it with a lucky blow from a spade. The remains were carried in a sack to a nearby barn and Mr Paddington informed. On investigating two hours later he could find no trace of the creature though Langham was most insistent as to the truth of his story. He was much shaken by his experience, and remained at home today. He described the attacker as ‘droning like a low-flying plane’ and claimed the sting alone, unsheathed in the death throes, was over a foot long.

Local police are at present investigating the deaths of three dogs in the vicinity. In each case the bodies were found considerably swollen and each animal appeared to have been killed by a thrust from some sharp-pointed weapon such as a stiletto or bayonet. Asked if the wounds could conceivably have been caused by some such oversize insect, a constable remarked that ‘if it was a wasp, he would not care to meet it’. Samples of tissue from the dead animals have been submitted for analysis with a view to determining what if any poison is present, though no report has yet been received.

There was a footnote.

The Curator of the Insect House at the London Zoo said today ‘The largest living insect known to science is a beetle, Macrodontia Cervicornis, which attains a length of almost six inches. The construction and operation of an insect’s body are such as to render any form larger than this highly improbable. A size of three feet or more would be out of the question.’

I put the paper down and shook my head. ‘I’ve heard some tales in my time but this takes some beating. Do you believe it, Tod?’

He took a pull at his Guinness. ‘No. It isn’t possible. And it’s just as well, sonny Jim, I’ll tell ye.’

I chaffed him. ‘How come? I should have thought you’d welcome it. Look at the trade you’d do squibbing away at whopping great things like that.’

He looked at me queerly. ‘You’d be laughing over the other half of your face if it was true, Bill. You think about it. Imagine a wasp. The power of it, the body of the thing packed with muscle and venom. You haven’t got an animal there, you’ve got a machine. All sheathed in with chitin, and that’d be tougher than steelplate. You’d need an armour-piercing bullet to hurt him and all the time he’d be coming on and coming on, and you’d never step from the way of him. And his sting, it would go right through you and come out on the other side, like the paper says it’d be a bayonet. And there’d be his jaws too, snipping away like bolt-cutters. Make no mistake, if a wasp was blown up to a yard big those mouth parts would have off your arm and no bother to it.’

I said, ‘Charming, I’m sure …’

He said, ‘There’d be other things of course. Things like social organization. He’s just as smart as we are at getting things done.’

I frowned. ‘You’re a mine of nasty ideas tonight, Tod.’

He grinned at me. ‘There’s things that get in a man’s mind and won’t be driven away, it’s the mystic Oirish in me I tell ye … I say the next great time will be the Age of Insects. If these big wasps were real we’d have it on us in a jiffy.’

I said, ‘That’s wrong for a start, insects missed their chance. They’ve been around for God knows how many years. If they’d been going to dominate they’d have done it before now.’

He shook his head. ‘Oh no … There were little dinosaurs scuttling and hopping for a good while before Tyrannosaurus sat up and barked. And take mammals, they spent long enough running about like cane rats before one of them built the Pyramids.’

Never argue with an Irishman. He revels in it.

‘Take a fly in amber,’ said Tod, warming to his theme. ‘See the little beast, the hairs of him, and his wings, and the twinkle in his eye. He’s a good few times older than the human race, but he’s just the same as the ones outside on the muck-heap. Now insects have waited a long time, and some of ’em with a social structure approaching ours an’ all, and they haven’t changed or evolved, they haven’t gone up or down. That means as living machines they’re pretty near perfect, which we most certainly are not. We’re shedding our poor teeth and claws and we need a whole mess of things to keep us alive and warm, we’re fast losing what adaptability we have left and that was bad for the dinosaurs.’

I said, ‘But insects aren’t adaptable either.’

He opened his bright blue eyes wide. ‘Ah now there ye go, dabblin’ in what doesn’t concern ye once again. Now if ye would just stick to the art of drawing and allow us professionals to know what is going on and what is not … Of course your insect is adaptable. If he wasn’t, I’d be lookin’ for a job. He can live on cyanide of potassium if he wants, we can’t. Look, there’s people in laboratories with real heads on their shoulders and they’re worryin’ to death because of running out of things to invent, and the little beggars of insects growing fat on last year’s sprays. I tell ye.’

I said, ‘Like the penicillin immunity.’

‘The very same …’ Something droned in the darkening sky, and he stopped. He said, ‘What do ye suppose the man saw then? Now what could come snapping and buzzing at ye like that, on a nice bright summer day?’

I didn’t answer. The noise got louder; then we both saw a plane fly across the window and disappear. Tod laughed. ‘I tell ye, I’m nervous already. You give a device like a wasp just this one little advantage of size and he’d be down on us from the air. Like the creatures in the story that tormented the poor souls for their sins, now what were they called?’

I said, ‘The Furies.’

He nodded slowly, sipping the drink and rolling it around his mouth. He said, ‘Yes, the Furies. Come to think on it now, that would be a good name for a pack of things like that …’

For the next few days I kept a curious eye on the newspapers, but there were no more reports, tongue in cheek or otherwise. Of course through most of that year nearly all news was overshadowed by the nuclear test series being run by both East and West. The American experiments were to culminate with the Neptune Project, the forthcoming detonation on the bed of the Pacific of a five-hundred-megaton bomb. It would be the biggest-ever man-made blast, and for nearly six months the Press had been retailing arguments for and against it. The Navy claimed with some asperity that the effects on tides and currents would be global and catastrophic while the fisheries people were worried about contamination; some authorities claimed it would be years before safe catches could be made anywhere near the affected areas. As I remember there were even some doubts expressed about the ability of the Earth’s crust to withstand the shock, though they were immediately howled down as alarmist and unscientific. For most of us of course there was nothing to do; we just sat around like saps and waited for the big bang.

From shortly after the signing of the first test-ban treaty it had been obvious that despite the drum-banging of the politicians, the agreement did not mark a new era in human development. For me the proverbial cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared when an American statesman declared that the signing represented a challenge to the forces of peace. We must keep alert, he said, so as to be ready to resume testing instantly if and when the enemy broke his word. Whether Russia actually did explode a thermonuclear device in the atmosphere is now, of course, of merely academic interest. American experts claimed to have detected a sharp increase in the world level of radiation; notes were exchanged between East and West, the United States protesting that the treaty had been violated, Russia retaliating by claiming the whole thing to be a Capitalist plot designed to shift the blame for what were in fact Western experiments. Shortly after that seismographs recorded heavy shocks which could have been and probably were underground trials in the vicinity of the old testing ground, Novaya Zemla. America, thoroughly alarmed, warned the Kremlin that she would not hesitate to continue her own experiments in the interests of world peace. Great Britain supported her by announcing an intention to ‘stand firm’, though how, and with what, was never made clear. Russia stayed quiet. Shortly afterwards the West announced the full-scale resumption of atmospheric testing. The event was efficiently publicized and the Russians rapidly followed suit by beginning a new series of their own.

It was rather like a drug addiction; after a temporary abstinence both sides returned to the habit with redoubled vigour. At the beginning of the year radiation levels stood fifty per cent higher than they had done in the scare of the late fifties, and the best was still to come. In Great Britain we saw a boycott of Welsh farm produce, and the Ministry of Health attempted to calm the populace by making a hasty upward revision of all safety levels. The Press began to remark on odd side-effects; one of the most significant was that, as during the London blitz, the churches began to fill.

A couple of nights after talking to Tod I had a visitor. It was about seven o’clock and dinner was well under way. I forget what I was trying to cook, but I’m sure it would have been better not to bother. The kitchen door was propped pessimistically open and Sek was outside somewhere. I heard her bark briefly, then again, then she was quiet. I stopped operations and called her. When she didn’t come I walked round the side of the house to find out what was the matter; a Dane never speaks without a reason. When I came in sight of the front lawn I stopped. I was a little taken aback.

The girl had already come through the gate and she was on her knees in the drive, Sek’s head towering above her. She was rubbing the great animal on the chest and Sek was standing there soaking it up and looking as sloppy as possible. The youngster straightened when she saw me; she was tall, she might have been fifteen or sixteen. It was hard to tell. She was neatly dressed in blue jeans and a check shirt; her face was round and rather serious with a straight, stubborn little nose and wide-spaced, candid blue eyes. She had a superb mane of dark hair, sleek and well brushed, caught up behind her ears with a crisp white ribbon. Altogether, a surprising vision. I said, ‘Well hello, who are you?’

She said, ‘Jane Felicity Beddoes-Smythe. How do you do?’ She held out her hand.

I said, ‘Bill Sampson, and I’m pleased to meet you. But that wasn’t very wise you know.’

She was bending down again, calling the dog. ‘What?’

‘Walking in like that. Sek might not have taken to you.’

‘Pooh, what rot. What did you call her?’

‘Sek. It’s short for Sekhmet. Go on girl, it’s all right.’ That to Sek; now that I’d arrived she had become more officious and she was avoiding the outstretched hand. She went forward instantly and allowed herself to be petted. I said, ‘What can I do for you, Miss Smythe?’

She looked at me blandly. She said, ‘Beddoes-Smythe. I don’t care, but Mummy likes to hear both barrels go off. It isn’t important though, I respond very well to Jane.’

I shook my head slightly. Her voice was beautifully modulated; it struck me she came from the sort of family who’re so wealthy they can afford to be polite. I said, ‘All right then, what can I do for Jane?’

She waved a well-thumbed exercise book. ‘I’m on vacation, we came down last week. I’ve got a holiday task that rather leaves me gasping, so I thought I’d bring it down and get the scientist to help me with it.’

I was baffled. ‘I’m afraid you’ve got it wrong. There’s only me here and I’m not a scientist.’

She giggled suddenly, tossed the book down, and started to wrestle with Sek, who was only too willing to play. She said, ‘That’s an alibi, I thought it was quite ingenious. I told the housekeeper you were a scientist and a friend of Daddy’s. Actually I just wanted to come and see the dog.’

I started to grin. I said, ‘Where do you live, Jane?’

She pointed briefly. ‘Over there. Brockledean House. Mummy and Daddy are away at the moment, they’re not expected back for some time. What’s that smell?’

I said, ‘God, the dinner …’ I pelted back to the kitchen. Smoke met me. I groped my way inside and got the pan off the stove. On the way out I nearly collided with Jane. She started to cough. She said, ‘What a terrible mess. Do you always get in a state like this when you try to cook?’

I finished scraping the remains on to the garden. ‘It isn’t usually quite as bad as this. But sometimes people call at the crucial moment. Then I forget, and things go haywire.’

She said, ‘Gosh, I’m terribly sorry. Can I help?’

‘No, it’s all right. I can cope.’

‘Please, I should feel much better. After all, it is my fault. Don’t worry, I’m quite good in a kitchen.’

‘I wouldn’t hear of it …’

She was quite the most determined girl I’d ever met. Half an hour later we both sat down to a first-rate mixed grill, far better than anything I could have cooked. I complimented Jane and she lowered her eyes in false modesty. ‘There’s a trick to it,’ she explained. ‘It’s very simple really. You get all the things you know are going to take longest and put them in first. Then the others. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...