7:00 P.M. – AUGUST 14, 2020

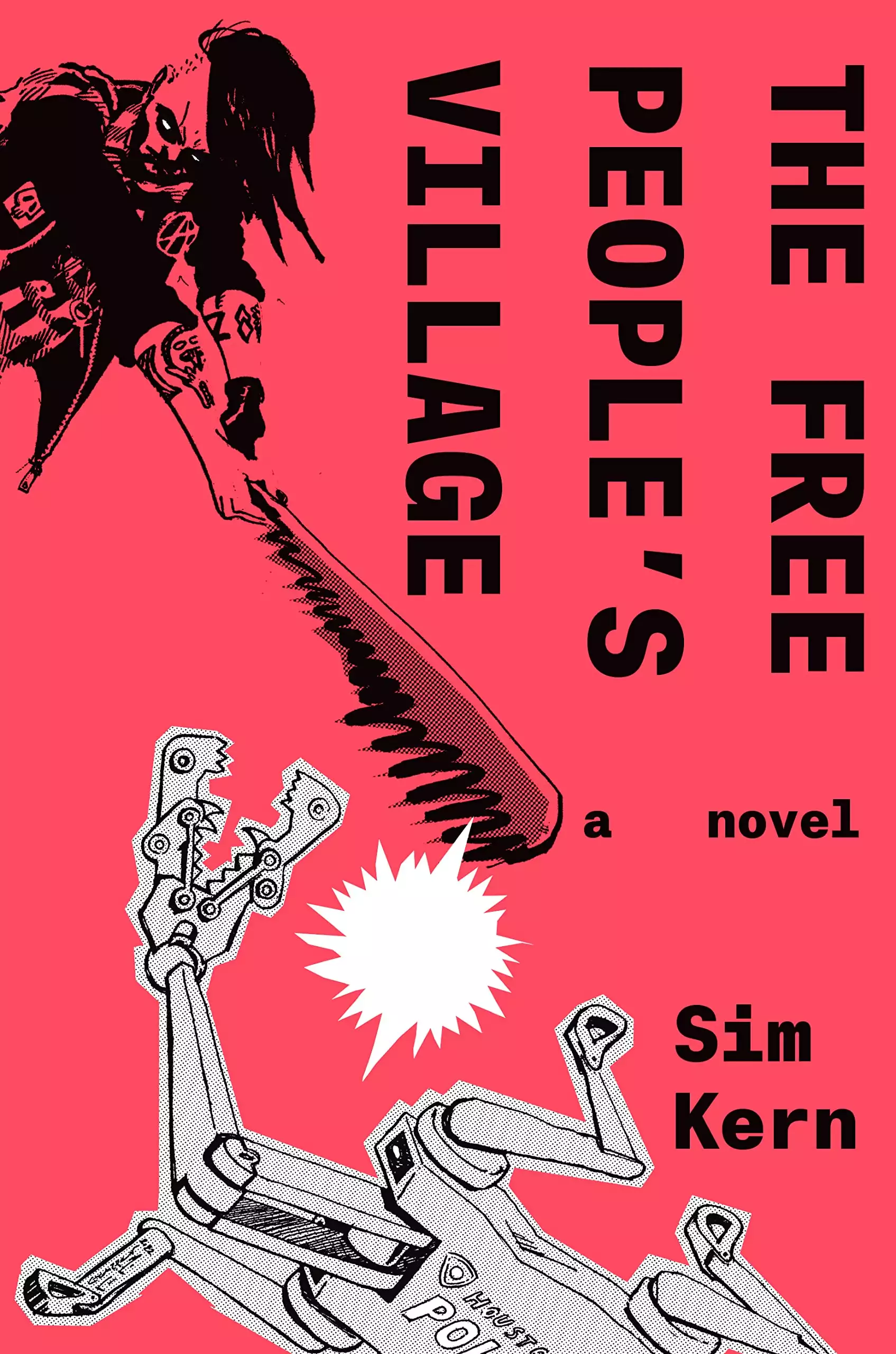

Iknow you want to hear about the Free People’s Village and that literal, fateful-fucking-step at the reflecting pool, but to explain why I did what I did, I have to start the story months earlier, before the tents and tear gas and stirrings of revolution, with the night of the last great party at the Lab—the night Red destroyed the Fun Machine.

I got to the house just before sundown. Even though I taught in the Eighth Ward, just a few blocks away, I always went home to change before a show. My friends would have roasted me alive for showing up to the Lab in one of my linen work suits. So after the last bell, I’d bike two miles to the G train—the only maglev station in Eighth Ward. I’d wait one or twenty minutes, depending on luck, watching the grackles argue in the live oaks around the station, feeling nervous, if I’m honest, as I was usually the only white person on the platform.

Then the G train zipped me to Midtown. After a few minutes, the old, brick cottages and shingle roofs of the Ward gave way to shiny Community towers—their tops angled and glittering black with solar panels. The landscape morphed from yards choked with invasive vines or flat-topped squares of Bermuda grass into swaying prairies, interrupted by the neatly maintained orchards surrounding each Community. Here and there, the prairie humped up in wildways passing over the maglev lines that spiderwebbed across this part of the city, with a stop for each Community and fast connections to Downtown, the Medical Center, and the Galleria. At each stop as we headed west, more Black people got off, and more white people got on.

Disembarking at my Community, I dashed from the station up to my apartment on the seventh floor. Threw off my stale work clothes. Threw on thrifted cotton shirt, denim shorts, and some alligator-leather cowboy boots I’d found at an estate sale. I threw on a thick coat of eyeliner, clipped a take-cup to my belt, and then it was back to the train, back through the prairie and over the bayou, past herons spearing fish along the rocky banks, and finally back through the time warp. To a neighborhood that hadn’t changed a bit in the last twenty years of the “War on Climate Change,” except that its potholes were wider now.

Navigating those craggy streets on my pop-out bike as the sun set was no easy feat. At least I didn’t have to worry about cars running me off the road, like they would’ve in the olden days. By 2020, the only cars left in the Ward were wheelless hulks in backyards, colonized by bees and weeds, too rusted to be sold for scrap. Only suburban people or rich folks had cars anymore—and those were all shiny, hyperway-compatible electrical vehicles. The carbon taxes on old-school gas guzzlers were so exorbitant that only the richest of the rich could afford to drive them, and all the gas stations in the city had been converted to rapid battery-charging stations.

Despite the treacherous pavement, I pedaled as fast as I could—acutely aware that I was a tiny white girl in a skimpy outfit. I was afraid of the clumps of old men who stood together, chatting on street corners, sipping from take-cups. Sometimes they hollered something as I sped by—nasty or nice, it felt threatening either way. I don’t know what made me pump my legs harder though—that vague, unspeakable fear, or the deep-down knowing that I didn’t belong there. That I was an invader.

I breathed easier rounding the turn onto Calcott, spotting the Lab up ahead, silhouetted by the last of the sun’s rays. Light and loud music spilled from the old red-brick warehouse’s windows and doors, every hole in that lovely, ugly face thrown open, filled with people of every race, gender, style, and subculture you could imagine, all of us so young—young enough to have no idea what kids we all were. Barely-adults like me, plus some teens who could be my students, though they never were. Except for Gestas, people actually from the Eighth Ward never came to shows at the Lab. They had their own places. The Black kids who came to our parties had white collar parents and lived out in the suburbs or university dorms. Crossing the Ward, they probably biked about as hard as I did to get to the Lab.

Cruising to a stop in the weedy front yard, I was finally home. The throbbing bass line spilling from the front doors enveloped me like a protective force field. I breathed in the haze of weed smoke and chemicals flaring off the refineries in the distance. The sun hadn’t set, which meant that the AC wouldn’t be on. Most of the early arrivers were standing around the yard in clumps, drinking keg beer from their take-cups, throwing back their heads in laughter, flashing their jugulars at the sky.

I collapsed my bike, stored it in my bag, and shouldered my way inside, past some blondes young enough to be in my English class. It must’ve been over a hundred degrees inside, and I sweat through my clothes in seconds. The front of the warehouse had once been offices that Fish had converted—rather terribly—into apartments. I popped my head inside Red and Gestas’s place, but they weren’t there. The guitarist from Okonomiyaki Riot was lying on Red’s bed though, strumming “Blackbird” on Red’s acoustic guitar while some groupies looked on adoringly. I felt a wild surge of possessiveness. Who the hell was he to be on Red’s bed, touching xir guitar? I shoved the feeling down, reminding myself for the thousandth time that Red was not mine to claim. I was sick of these waves of intense, nonsensical jealousy.

I wove through the crowd in the hallway between the apartments and passed through the door to the main warehouse space in the back. It was cooler in here, as the sliding back cargo doors were thrown open to the dusk air. Still, it was probably 90 degrees, and the few dozen people inside were slumped against the walls or on the curb-scrounged, greasy couches that interrupted the room. Vida was painting an armadillo wizard over a hundred scrawled tags on the back wall, and the bassist from Okonomiyaki Riot was skateboarding down the strip of empty space in the middle of the warehouse.

In the corner that was the unofficial “stage,” Fish was plugging in our amps and Red was setting up xir mic stand. I was still Fish’s girlfriend, but I’d been wondering for a long time how to extricate myself from that relationship without destroying the band. It was Red—tall and laconic, sweat-slicked black hair falling across xir eyes—the sight of Red made my heart fly off in wild, syncopated rhythms, like Gestas tearing into the drum solo at the end of “Don’t Think About Death.” It’s how I’d felt every time I’d seen Red over the past year, ever since I’d first laid eyes on xim—that cicada-filled afternoon, when xe stood in the doorway to xir apartment, twirling a red patent leather shoe by its heel.

AUGUST 2019

When my co-teacher first introduced me to Fish, he’d seemed so exciting. Or maybe that was the bar. I was newly divorced, and I’d never been in a place as seedy as Poison Girl, where a thick coating of grime caked the sticky tables, and taxidermied animals, and velvet paintings of topless women decorated the walls from floor to ceiling. The “good Catholic” voice in the back of my head shrieked that this was a den of sin and sodomy, but I’d made a decision to stop listening to that crusty old fart. In fact, I was making a habit of doing the opposite of whatever she said. Above the shelves of whiskey bottles were four especially mesmerizing paintings. The artists had used just a few brushstrokes to highlight the full breasts and long stomachs of gorgeous girls on soft, black fabric, and I couldn’t tear my eyes away from them long enough to catch the bartender’s eye. The nun in my head yelled, “Lesbian! Queer! Whore!”

I let myself revel in the thrill. Maybe I am, I thought. So what?

My co-teacher dragged me outside in that heady state, to a gravel backyard strung with party lights, where cockroaches occasionally flew down from the trees into shrieking girls’ hair. At a table next to a giant papier-mâché Kool-Aid Man weathered by the elements to a dull pink, she introduced me to a guy named Fish.

It’s painful now for me to remember being attracted to Fish, but I was that night. Maybe my feelings for the girls in the paintings got transferred onto him. Maybe the realization that I might be queer had, in fact, freaked me out, and I was grasping for proof of my heterosexuality. Or maybe it was because Fish was the polar opposite of my ex-husband, Colton.

Colton and I had split after four years of marriage when I was the ripe old age of twenty-two. Where Colton had been all compact, hard muscle from marathon training, Fish was a soft, six-foot-two giant. Instead of clean-shaven and buttoned-up, Fish had a wild red beard, mad-scientist hair, and wore torn band T-shirts and jeans. And after being married to a man who’d made me kneel in prayer with him before and after every sexual encounter, the “Hail Satan” tattoo sprawled down Fish’s forearm held a magnetic fascination for me. I wanted to lick it.

At the bar that night, Fish was so animated and charming—I didn’t realize that he was just in his buzzed sweet spot, somewhere between three and ten drinks. He paid for all my beers and told me about the great bands he hung out with in Houston, how he was about to close on a property in the Eighth Ward—right near my school—which he was going to turn into an anarcho-communist creative space. He had all these big dreams for throwing shows and art installations, and having a farmer’s market and makerspace there. The way he talked about all the things he was planning for the Lab, I expected it to be ten times the size it was. I asked him how he’d gotten the money to buy such a place, and he told me about his app.

Of course I used CarbonSwap. Everyone did. Back then, it was the only way to transfer small amounts of carbon credits using your phone. Me and the other teachers had used it that very night to come up with the carbon tax for the pepperoni pizzas we’d split. At first I didn’t believe Fish was really its creator, but he pulled up an article to show me. There he was, the twenty-three-year-old wunderkind who’d dropped out of college and created a multimillion-dollar app. Of course, none of those puff pieces explained that Fish had only been able to drop out because he had a cushy trust fund to live off of, which he’d used to criminally underpay the guy who did the actual coding for CarbonSwap. But I’d learn about that months later.

I bought Fish’s story of being a self-made millionaire tech genius. None of the teachers I worked with had dreams any bigger than going on a solar cruise to Cancún for spring break. Meanwhile, Fish wanted to engineer a new society, starting with this “Lab.” And the nun in my head hated him, so that was an endorsement. He was my ticket to the secular, hedonistic world of rock ’n’ roll and bad choices, and after surviving the last few years of my miserable marriage, I wanted in.

So I went home with him that night.

He closed on the Lab the next day. A week later, I’d overhear him joking to the dudes in Venus Gashtrap that if bragging about the Lab hadn’t gotten him “such good pussy,” he might not have signed on it.

What a charmer.

A few weeks later, he took me to see the Lab for the first time. My footsteps echoed in the big, empty warehouse, and the sun streamed through high windows onto a clean, cement floor and walls that were still painted stark white. Fish gestured around the space, showing me where he was going to have the zero-waste food shop and the community 3D printer. Even then, I could tell there wasn’t enough room in the space for even half his big dreams, but it was still fun to hear him go on about them. I believed he’d at least make a few of them come true, and I suppose he did. We had plenty of art installations and countless shows at the Lab, but we never did get the bike shop set up or the fibers studio.

Fish must’ve stepped outside to take a phone call or something, because I found myself alone in the cavernous space. I heard voices coming from the cracked door to the front offices. Fish had moved into the second-floor-turned-loft-apartment a few days ago, and he’d told me that a local band had already claimed one of the ground-floor apartments. He was giving them a steal on the rent because he loved their music so much. Bunny Bloodlust, a guitar-and-drums duo. He hadn’t shut up about what geniuses they both were.

Curious to meet his new tenants, I stepped into the hallway to the apartments. The left-side door was wide open, and someone was picking guitar inside. Now that I was in the hallway, I didn’t know what to do. Embarrassed for snooping, I made a beeline for the front door, but as I passed the open apartment, someone called out, “Hey, is this your shoe?”

I turned, and that was the first time I saw Red, leaning against the doorframe, twirling that shiny red pump by its heel. Right away, my heart started skipping every other beat, but at the time I figured I was just nervous about meeting someone who—according to Fish—was a local music god. I didn’t know that, up to that point, Bunny Bloodlust had only recorded a three-track EP. They’d never even played a real show, thanks to Gestas’s legal status.

“It’s not mine,” I said about the patent leather shoe. “That’s not really my style.”

“Huh,” Red said, scanning my “style” up and down. I cringed, realizing I was still wearing my dorky, linen work clothes. “Some girls were over here last night. I figured you might’ve been one of them.” Red stepped back inside the apartment and chucked the shoe in a corner, but the door was still wide open. I couldn’t tell if I’d been dismissed or invited in.

“You want a beer or something?”

Heart in my throat, I stepped inside, where Red was filling a take-cup from a keg in a corner. There were clusters of empty malt liquor and whiskey bottles around the room, and the whole place had that stale-beer-and-weed stink of the day after a party.

“I’m Red, by the way. Xe/xim. That’s Gestas, he/him.” Red nodded at the dark-skinned Black guy on the futon, fingerpicking a melancholy bluegrass tune on an acoustic guitar.

If I’m being honest, which I never was back then, I was scrambling to “figure out” Red’s gender. I’d never hung out with a trans person before. I’d grown up in this queer-hating, strict Catholic world. My brain still wanted to lump people in one of two categories, but I couldn’t figure out which Red was. And I couldn’t figure out xir ethnicity on sight either. Xir skin was light brown or dark olive. Sharp-cornered, brown eyes and black hair, buzzed short on the sides, and long enough on top to crest on xir forehead. Eventually, of course, I learned what gender Red had been assigned at birth, and which of xir ancestors had colonized which others. But Red lived for the squeamishness of white, cishet people not being able to figure out just “what” xe was.

Gestas’s gender presentation also made my head reel. He went by he/him, so okay, I thought, he’s a guy. But he was wearing this torn, macho-looking, heavy-metal T-shirt with a baby-pink, pleated, A-line skirt. He had a scraggly, curly beard, but sparkly gold eye shadow from the night before was smudged all around his dark-brown eyelids. I’d never met someone so masculine and so feminine at the same time. Colton would’ve spat out his coffee at the sight of Gestas, and that was enough for me to like him on the spot.

I clocked, then quickly glanced away from the glowing, green light embedded just beneath the skin of Gestas’s right shoulder. Fish had told me about this—that one of the new tenants was an AHICA inmate, confined to the property through the At-Home Incarcerated Criminals Act. I’d never met an AHICA inmate before, even though I knew there were tens of thousands of them all throughout the city, stuck inside their homes.

I must have introduced myself, and I hope I remembered to share my pronouns. I took the offered beer but felt too nervous to drink much. There was another guitar sitting on the futon beside Gestas, and I picked it up, at first thinking to just move it out of the way. But it found its way into my lap instead. I wanted to impress them, wanted to show them both that I wasn’t just some red-heeled groupie they could party with one night and forget the next morning.

I put my ear right up against the fingerboard and barely grazed the strings to check that it was in tune. I listened to Gestas for a few bars, watched his fingers, figuring out the chords. He cocked an eyebrow at me curiously. He settled into a pattern. I strummed a harmony. He moved through a key change. I followed. He sped up, changed the time signature, and I chased him, rounding out his melody. Then he settled into a predictable chord progression, and it was my turn to take the lead. I locked eyes with Red, who was watching us with an unnerving, crooked grin. This was—what? An audition now? A sudden, nervous sweat broke out all over my body. I tried to chart a melody, but I hated the way it was coming out. Too happy, too much C and D major—nothing like Gestas’s haunting tune had been. I was gripped with this wild, irrational fear that they were laughing at me, that they could tell all my music was hopelessly infected with Christianity and youth-group aesthetics. I blanked on how to resolve the line. The notes came out jarring and dissonant. “Sorry,” I muttered, staring down at the guitar, gut roiling in shame. Expecting them to—what? Laugh at me? Chase me out of their apartment?

“Don’t apologize,” Red said. “That was just getting interesting.”

“You’re pretty good,” Gestas said, and I must have blushed the color of the orphaned high heel in the corner.

Red reached for the guitar in Gestas’s hands, and he offered it up, plus his seat, settling again behind a banged-up, glittery pink drum kit in the corner. He started playing a 4/4 beat, softly, inviting in our guitars. Red took the lead, and for the first time I got to watch xim coax a narrative from the strings. Xe improvised an aching melody, twisted it with tension, then resolved it with a glimpse of a peaceful pasture, before plunging the line into anger and despair. Xe made it seem effortless. I fucked up following some of the chords, but for the most part, I was able to add fullness to xir sound. I don’t know how long we played—it could have been ten minutes or an hour. Through the music, we were telling each other a little of what we knew about pain and loneliness and the beauty that springs up in the ugliest places. I started to feel like we’d all known each other for ages, even though we’d still only exchanged a handful of words.

Red resolved a line and stilled xir strings. Gestas faded the drums out with a shimmering brush on the snare.

“Do you play bass too?” Red asked. “We’ve been talking about getting a bassist.”

I was shaking my head no when a voice boomed “I do!” from behind me. Fish had been listening in at the doorway for god-knows-how-long. He strode into the room and placed a hand on my shoulder. That was the first time I ever flinched at his touch.

“I’m not as good as you guys, but if you can write down the chords for me, I can keep up. I’ve actually got a vintage Ibanez five-string upstairs, real beauty, that’ll work great with your sound. And have you thought about upgrading your amps and mics? Because I can totally hook you up with that—and any pedals you need. I wanna invest in y’all! You don’t have to let me perform with you or anything, to pay me back, but it’d be hella cool to jam together sometimes. I mean we all live here now, right? Band house!” He pumped a fist in the air. “So cool!”

“You’re with him?” Red asked, cocking an eyebrow at the heavy hand resting on my shoulder, an unmistakable note of derision in xir voice.

“Maddie’s the one who convinced me to sign on this place!” Fish boomed. I squirmed uncomfortably, knowing that he meant that I’d slept with him after he’d bragged about the Lab. I already regretted my entanglement with him. But Fish owned the building. Soon he’d own all the band’s sound equipment. And I would put up with him touching me, way longer than I had any desire to, because I thought that if I ditched him for Red, he’d kick xim out of the house, destroy the band, and use his ever-growing connections in the music scene to make sure Bunny Bloodlust never played another show in town. So I let him buy me dinner, and a new amplifier, and a season pass to my body.

Playing with Bunny Bloodlust was the only thing that had seemed to matter since I’d gotten divorced, and lost my faith, and the world turned flat and dull. Even with Fish dragging the rhythm on the floor behind us, playing with our band was the first time in my adult life I’d felt excited about being alive.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved