- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

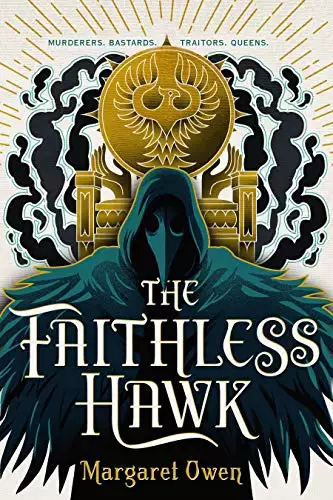

Kings become outcasts and lovers become foes in The Faithless Hawk, the thrilling sequel to Margaret Owen's The Merciful Crow.

As the new chieftain of the Crows, Fie knows better than to expect a royal to keep his word. Still she’s hopeful that Prince Jasimir will fulfill his oath to protect her fellow Crows. But then black smoke fills the sky, signaling the death of King Surimir and the beginning of Queen Rhusana's merciless bid for the throne.

With the witch queen using the deadly plague to unite the nation of Sabor against Crows—and add numbers to her monstrous army—Fie and her band are forced to go into hiding, leaving the country to be ravaged by the plague. However, they’re all running out of time before the Crows starve in exile and Sabor is lost forever.

A desperate Fie calls on old allies to help take Rhusana down from within her own walls. But inside the royal palace, the only difference between a conqueror and a thief is an army. To survive, Fie must unravel not only Rhusana’s plot, but ancient secrets of the Crows—secrets that could save her people, or set the world ablaze.

A Macmillan Audio production from Henry Holt and Company

Release date: August 18, 2020

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Faithless Hawk

Margaret Owen

KINGS AND OUTCASTS

CHAPTER ONE

THE THOUSAND CONQUESTS

Fie was taking too long to cut the girl’s throat.

It wasn’t the act itself; in the three weeks since taking charge of her band of Crows, Fie had dealt mercy more than a handful of times. Tavin had told her last moon that killing never ought to get easier, but that it did anyway. Too many lives had ended on the edge of her steel since then to pretend that didn’t hold a speck of truth.

No, the sticking point now was the sinner girl.

The girl had been sitting up on her pallet when Fie walked into the quarantine hut, dark eyes imperious, mouth set in a stiff bar like the one sealing the door from the outside. Her short-sleeved linen shift was well made but plain for the Peacock governor’s only daughter, her black hair in a clean, glossy braid that hadn’t yet frayed and dulled with fever sweat. A scroll had sat half unfurled across her lap. Just enough near-noon sunlight soaked the canvas-screened windows for her to read by.

Fie reckoned the Peacock girl was near her own age, somewhere closer to seventeen years than to sixteen. But delicate rings of dark-veined rash had begun blooming at her temples, slight enough to be only hours old, damning enough to say the girl had only hours left.

Minutes, now that Fie had come for her.

Most of the time Fie found her sinners delirious, dazed, even dead; the Sinner’s Plague never let any soul slip through its grasp, and it wrung even the simplest dignities from its victims along the way. Never before had a sinner watched Fie so, like she was a wolf strolling too near a pasture.

Fie ought to have left her mask on. Instead she took it off.

She ought to have drawn the broken sword. Instead it stayed at her side.

She ought to have told the Peacock girl to close her eyes. Instead, she jerked her chin at the scroll and asked, “What’re you reading?”

The Peacock girl leaned back, gaze narrowing. Her lip curled. “It doesn’t matter. You can’t read anyway.” She tossed a small, clicking bag at Fie. “There. Do it fast and clean.”

The bag was full of milk teeth, and when Fie fished one out, its spark sang loud and harsh in her bones. Niemi Navali szo Sakar, it declared, daughter of—

Fie yanked her hand out. The tooth had been Niem—the sinner girl’s, and it’d stay noisy until she died. Others in the bag kept quiet, but Fie picked out the song of Peacock witches among them. The governor’s dying daughter meant it as a bribe.

“Not how it works,” Fie said, tying it to her belt, “but we’ll call it a tip.”

“Just do what you’re here for already.”

Fie shrugged, brushing her cloak aside in the same movement, and drew the swords buckled at each hip. One was from Tavin, the Hawk boy she’d left behind: a beautiful short sword wrought of finest steel, gleaming demurely in the diluted sunlight. The other sword could barely be called such: an old, battered blade, broken half through, its end no more than uneven jags. A Crow chief’s sword, good for mercy alone. That sword had come from Pa, who she soon would have to leave behind as well.

Fie didn’t care to dwell on that. Instead she held out both blades and asked, “Which do you want?” As the Peacock girl’s face turned gray, Fie shuffled closer to give her a better view … and to give herself one as well. The letters on the scroll ordered themselves into words for her, faster now thanks to regular reading practice. “Oh. The Thousand Conquests. That’s a load of trash.”

The Peacock girl snapped the scroll up, scowling. “Of course you’d think that. I don’t expect a Crow to have taste.”

“I’m around conquest … two hundred?” Fie drawled. “Out of a thousand? So far the only Crows have been dirty, thieving half-wits. Or monsters. Scholar Sharivi seems to think the Peacocks piss ambrosia, though, so I see the appeal for you.”

“It’s the truth,” the sinner girl hissed. “Peacocks are born to rule. The Covenant made you as a punishment.”

Fie had heard it before; she supposed that to most of Sabor, it seemed clear-cut. Every other caste was born with a Birthright, an innate gift passed down from the dead gods, like a Crane’s way of spotting lies or a Sparrow’s way of slipping from unwanted attention. Some were even believed to be dead gods reborn into the castes they’d founded, like the Crane witches, who could pull the truth out of a liar, or a Sparrow witch, who could utterly vanish from sight.

The dead gods, though, had denied the Crows a Birthright of their own. Their witches could only steal the Birthrights from bones of the other castes, and only as long as a lingering trace of its former life lasted in that bone. And as the only caste immune to the Sinner’s Plague, their trade was cutting throats and collecting bodies.

With all that, Fie didn’t doubt the life of a Crow sounded like a punishment to a highborn Peacock. Most of Sabor believed dead sinners were reborn into the Crow caste so as to atone for whatever crimes had brought the plague down on them to begin with.

And yet …

She crouched on the dirt floor, setting her swords between her and the Peacock. “Funny thing is, were I to think on which of us two the Covenant favors right now—” Fie tapped her cheek. “Reckon that’s where the scholar Sharivi and I would disagree.”

Fie expected the Peacock girl to sneer at her, to lash back.

Instead, Niemi closed her eyes and raised a hand to the Sinner’s Brand rash on her face. Her voice cracked. “I … I suppose you’re right.”

A tiny, cold scrap of guilt knotted in Fie’s gut. Aye, she despised this soft, clean girl, and not merely because the girl despised her. Yet only one of them would leave this room alive.

Pa would tell her to stop dragging it out.

Wretch would tell her not to play with her food.

Instead, Fie asked, “Do you know why the Covenant picked you?”

The Peacock’s lips pressed together. Her finger shook as she pointed to the Hawk sword. “I want that one.”

“Rich ones always go for the fancy sword,” Fie mused. “You didn’t answer me.”

“Just get it over with,” the girl spat.

Fie lifted The Thousand Conquests and began rolling it up. “Been about five years since Crows passed through the lands of Governor Sakar, aye?” The parchment let out a particularly belligerent crackle. “Heard the last band didn’t make it out of here. Most of them, anyway.”

The Peacock girl said naught.

“A boy got away. Another chief found him, brought him to my pa. His name was Hangdog.”

Was. Two moons since he’d tried to run from being a Crow. Two moons since he’d died on the steps of a Peacock mansion.

When Fie had been old enough, Pa had told her what had happened to Hangdog’s first band. Hangdog himself had spoken of it to her only once.

“He told me there was a rich girl who came to their camp. They let her look at the pyre, they let her wear a mask, they let her see the chief’s sword, because you don’t say nay to a Peacock, even a little one … and then that night, the girl led the Oleander Gentry straight to their camp.”

The Peacock girl’s hands fisted in her pristine linen shift. Another bloom of Sinner’s Brand had begun to tattoo her forearm.

Most of Sabor liked to think the Covenant meant for Crows to be punished. By Fie’s ken, the Covenant had naught to do with it; they’d just appointed themselves its hangmen.

Niemi Navali szo Sakar turned a furious, glittering gaze on Fie. “I’d do it again.”

Fie gave her a humorless, toothy smile and tucked The Thousand Conquests into her belt. “Suppose that’s why the Covenant calls for you, then. Lie back.” The girl didn’t move. Fie pointedly hefted the Hawk sword. “Can’t steady both you and the blade.”

The Peacock girl lay back.

Sweat beaded her face. “Will it hurt?”

Fie had seen thousands of lives by now, ghosts darting like minnows through her head as she pulled Birthrights from their long-dry bones. She’d seen the lives of kings and outcasts, lovers and foes, conquerors and thieves. Some ended in blood, others in quiet. Some had even died at Pa’s hand, a cut throat granting them mercy from the agony of the Sinner’s Plague. She saw those lives, and those deaths, more than any other.

“No,” Fie lied, and rested the blade against the sinner girl’s throat.

The clean steel shivered with every heartbeat pounding along the girl’s neck, harder with fury, faster with fear.

The Peacock girl drew a shaky breath and caught Fie’s eye. “The Oleander Gentry will come for you tonight, you know.”

She meant it as a promise. As a threat. As a reminder, even now, of which castes the Covenant favored.

And that was where she’d fouled up.

Fie bestowed her one more smile, cold and benevolent as the steel on the girl’s throat. “Let them.”

The truth was, it had never gotten easier to deal mercy to sinners.

But sometimes, they made it easier.

* * *

In the last three weeks, Fie had learned a handy new trick to negotiating the viatik.

When Pa had been the one cutting throats, he’d done his best to at least rinse off his hands after. The blood spooked the next of kin, he’d explained, and sometimes that made them pay the Crows more to speed them along, but more often than not it just made the mourners clutch their purses tighter.

Fie didn’t bother. If anything, she made a show of slowly peeling away the bloody rags knotted up to her elbow while the family’s representative presented their viatik. No one wanted to count coin into a palm still red and slick with mercy.

And that was the idea.

The Sakars had dispatched a Sparrow to deal with Fie, one who wore the simple fine robe of household servants, one whose red-rimmed eyes said she’d been close to the dead girl. A nursemaid, then. In one hand sat a fat bag of naka for viatik; the other hand skimmed the clinking coins, bitterly weighing out a meager few.

The thing about viatik, Fie had learned over years and years of experience, was that someone was always trying to short them.

Sometimes it was because they thought the Crows couldn’t count and wouldn’t know they’d been cheated. Sometimes it was because they wanted the Crows to know they’d been cheated, to remind them they still couldn’t demand fair pay without pushing their luck. This Sparrow woman, Fie reckoned, had the same instructions as too many servants she’d dealt with. Each and every time, they were handed a fat purse, but told to give the Crows as little as possible.

So in the last few weeks, Fie had learned not to let them.

The Sparrow nursemaid flinched back at the gore on Fie’s arms, eyes brimming with tears. Fie shook her head, flicking sweat from her hair. They’d kept to the north for most of Crow Moon, but midsummer humidity had invaded even this territory. “Naught to fear. You can hand the viatik to my lad Khoda.”

Fie could see the sums scratching through the nursemaid’s skull; by the time she’d tallied up that Khoda wasn’t a Crow name, it was too late. A rangy, iron-faced Hawk lad stood before her, hand outstretched, a spear leaning rakishly against his shoulder.

The trick, Fie had learned, was to make them hand the viatik to someone they couldn’t risk cheating.

A flutter of silk on the nearby veranda caught Fie’s eye. Two Peacocks stood there, still in their sleeping robes and clinging to each other, faces hard. The Sparrow servant looked up to the governor and her husband, questioning, as the quarantine hut’s door creaked behind Fie.

Last night they’d had a daughter.

Now, Madcap and Wretch were loading aught that was left of her into the Crow’s wagon, bundled in bloody linen.

Governor Sakar gave a stiff jerk of her chin, then buried her face in her trailing silk sleeves.

The nursemaid swallowed. Her bag of naka jingled like a bell as it landed, whole and hearty, in Khoda’s hand.

Fie caught a muffled snort from Madcap, one that turned into a cough. Not three moons ago, such a bounty would have been unthinkable, even a burden—just one more thing the Oleander Gentry would hunt them for. But now …

Khoda was one of five Hawks who had volunteered to escort Fie’s band as they answered plague beacons. And since acquiring their escort, a peculiar miracle had occurred. Not only did people start paying them fair viatik, but for the first time, they’d been able to keep it. No Oleanders had raided their camps; no Hawk posts had shaken them down for bribes. Fie’s band had left generous donations in every haven shrine they’d visited, and still they had more than enough to last until the next viatik.

And now they had a bag of coin near the size of Fie’s head. She hadn’t even needed to call a Money Dance.

“That’ll do,” Fie said, and wet her lips to whistle the marching order.

“Wait!” The Sparrow pointed to the scroll cinched in Fie’s belt. “That’s … that was her favorite.”

The Thousand Conquests. Where the Splendid Castes were beautiful and wise, the Hunting Castes were brave and true, and the Phoenixes were near good as gods.

Where Crows were thieves and fools and monsters and naught more.

“It’ll burn with her,” Fie said. The nursemaid’s shoulders slumped in relief. Fie added under her breath, “We all win.”

The Sparrow woman blinked at that. “Wh—”

Fie whistled the marching order and strode down the road before the woman could sum up aught else.

A familiar jingle said Corporal Lakima had fallen into her self-appointed place a step behind Fie, each thud of the Hawk’s boots measured as if rationed out to the greedy road. At first Fie had found it eerie, the creak of leather, the shadow doubling hers. She’d found it near as unsettling when Corporal Lakima asked her for orders.

By now, Fie supposed she was used to both. They made for an odd funeral procession rattling down the dusty gravel: a wiry twist of a girl chief in her beaked mask, a shadow of a Hawk looming at her back, nine more Crows towing their dead sinner in the cart, three Hawks bringing up the rear. They’d left Pa and the remaining two Hawks with their other cart, back at the flatway.

Even a second cart seemed an unfathomable luxury. They’d never before had enough to merit a second cart, never enough hands or beasts to pull one. But with Hawks to feed and plentiful viatik, things were a-shift. Now they towed one cart for their supplies and one just for sinners.

“Was there a problem with the girl?” Corporal Lakima’s voice ground near as low as the gravel.

Fie shook her head. “Only her mouth. That won’t trouble anyone again.” She picked at the sweaty straps on her mask, more jitters than aught else. They’d keep the masks on until the Peacock manor fell out of sight. “She said the Oleanders will come tonight.”

Corporal Lakima was perhaps the stoniest Hawk Fie had yet met; at a decade older and a head and a half taller than Fie, she did not so much stand on decorum as plant both feet into it and wordlessly dare anyone to push her off. She was not prone to a mummer’s theatrics. And so when Fie caught an exasperated wheeze before the corporal answered, “Understood, chief,” Fie thought at first it had come from the cart. She’d expect a dead Peacock to grumble sooner than Corporal Lakima.

“Did you just sigh?” Fie asked, incredulous.

Lakima coughed. “Did she say when they’ll arrive?”

“Just tonight. Suppose I ought to have asked for specifics before I cut her throat. You sighed.”

“These lowlanders seem to have a surplus of time on their hands.”

Fie snuck a look back. Lakima kept her face blank, her eyes locked solely on the road ahead, but a divot between her brows said the corporal was vexed. Oleanders meant a late night for her and her Hawks.

Three moons ago, before they’d smuggled Prince Jasimir across Sabor, Oleanders would have meant rolling gambling shells with disaster. If Pa had been promised a visit from the masked riders, he would have hurried them along through the night, not even stopping to burn the sinner until dawn peeled the cover of dark from the roads.

But Fie was chief now. Fie had Hawks now. And Pa …

He’d asked her to bear northwest to the Jawbone Gulf a week ago, and that was when she knew his time had come.

That was a trouble Fie’s Hawks couldn’t remedy.

Instead, she said to Lakima, “Maybe they’ll show up early and get it over with before dinner.”

Corporal Lakima lifted her spear in salute. It took Fie a moment to realize it wasn’t to her but to the Hawks on duty at the manor’s signal post above. Helmeted heads jerked back over the small tower’s platform when Fie turned to look their way. A thin wisp of black smoke still lingered from the plague beacon they’d lit to call Crows here.

Likely the Hawk soldiers couldn’t fathom why some of their own would accompany Crows. Fie failed to stuff down a smirk at that. She’d won her Hawks fair and square from Master-General Draga, and more importantly, she’d won Hawks to guard the whole Crow caste once Prince Jasimir took the throne. Those soldiers just might be escorting their own band of Crows soon enough.

Rumors had already floated past Fie, rumors of Crown Prince Jasimir, who’d survived the Sinner’s Plague like his legendary ancestor Ambra, and tales of Master-General Draga’s showy procession to return Jasimir to the capital city of Dumosa. Nobody spoke of Queen Rhusana, but Jasimir had always sworn the queen’s first move in a takeover would be to remove King Surimir from power, and so far it seemed the king breathed yet.

Considering the leader of Surimir’s armies was personally ushering the crown prince—the one Rhusana had repeatedly tried to assassinate—back to his home, Fie reckoned the queen might be keeping a low profile.

“Why did you take the scroll?” Corporal Lakima asked.

Fie had a score of answers to that: Because it made her feel better about cutting the throat of a girl her own age. Because that scroll told the nobility they were always good, and told Fie she would always be a monster. Because no one in the fine Peacock manor behind them knew that in Crow story and song, the monsters usually wore silk.

“They would have burned it anyway,” Fie said instead. “This way I get to watch.”

Lakima coughed again. “Ah. Must be The Thousand Conquests.”

* * *

Fie shed her mask once the roughway led into the trees, but she kept her eyes nailed to the road, only glancing back every so often to be sure no spiteful mourner tailed them. Five years might be enough for the woods to reclaim the campsite where Hangdog’s kin had died, but Crows were raised with an eye to spot potential sleeping grounds, and Fie didn’t feel like laying hers on that sad clearing.

She didn’t feel like thinking much on Hangdog at all.

Fear had spurred him to turn traitor, that she knew. Fear of what lay down his road as a Crow chief, fear that it would end as the rest of his kin’s had. She couldn’t fault him for that.

But she could fault him for thinking treachery was his only way out.

Fie felt the flatway before she saw it. The air savored hotter and dustier, the roughway began to even out, and full sunlight stabbed more frequently through the green canopy overhead. Finally they emerged onto the broad, smooth dirt road. Pa and their two other Hawks were sheltering with the supply wagon on the other side of the flatway, in the shade of an ivy-choked hemlock.

Fie’s heart gave a familiar sort of pang when she saw Pa, as it had done many a time since he’d asked her to lead them to the Jawbone. Then she kenned the look on his face, and that pang wormed into a deeper worry.

It was a rare look. Fie remembered the last time she’d seen it, all too close, all too clear: when Pa had handed her the sword, the teeth, and the prince, and sent her and the lordlings over the bridge in Cheparok.

It said something had fouled up, and in a way they might not be able to outrun now.

“What is it?” Fie called, striding across the dirt road—but the moment she broke into the sun, she saw.

To her left, a black string of smoke frayed the horizon, half a league away. To her right, another black thread unspooled. Beyond them, even more black trails rose until they’d striped the noon sky like teeth in a giant’s comb.

Fie had seen such a sight only twice before, but she knew square what black beacons for leagues and leagues meant.

Even with Prince Jasimir’s armies nigh at her door, Rhusana had made her move.

The king was dead.

CHAPTER TWO

STOLEN

“Welcome to our roads, cousin.”

Fie cast a palmful of salt onto the pyre, then took a step back from the flames licking up the dead Peacock’s shroud and thought a quick prayer to the dead Crow goddess who claimed the plague-dead, the Eater of Bones. Most of Sabor believed the sinner girl would be born as a Crow in the next life, to atone for whatever she did that made the Covenant snatch her so swift from this one.

Fie didn’t know if that were true, but if it were, she sore hoped the girl would learn to be less of a hateful hag.

“Didn’t sound like you meant that welcome,” Pa said by her side.

The Thousand Conquests twisted in Fie’s other hand. She’d washed up with soap-shells and salt, yet firelight still painted her fingers red against the pale, crumpled parchment. “I don’t.”

“She’ll be a babe when she comes to us as a Crow,” Pa said.

“Better come to someone else’s band.”

“Fie.” Pa set a hand on her shoulder. “It changes naught.”

He didn’t mean the girl on the pyre.

“It’s the last day of Crow Moon and the king dies? They’ll put us at fault for it, Pa.”

Pa ran a hand over his beard. “And it’s been two moons since we were there. Anyone who faults us for it is just looking for something new to blame on Crows. Likely they’re already riding with the Oleanders.”

“But it doesn’t add up, either.” Fie shook her head. “We’ve still two weeks until the solstice, when a proper Phoenix would be crowned. Jas is sure to make it to the royal palace before then to stake out the throne, and he’s the one bringing the armies. And now half the nation thinks he’s Ambra reborn, sent here to lead us into a new bright age … so since when does Rhusana’s kind pick a fight they know they’ll lose?”

The firelight caught on the knob of scar tissue where Pa’s little finger had once been. He’d lost it in just such a fight. “Aye,” he said. “It doesn’t add up for the queen. But what are you to do about it?”

“What?”

“You’re a Crow chief, leagues and leagues away from Dumosa. What are you to do?”

Fie wrung the parchment in her hands. She knew the words all too well, yet they felt like shackles tonight. “Look after my own.”

Pa squeezed her shoulder and let go. “Let the royals roll their fortune-bones. We’ve no part in their games now, and however their bones land, we’re still chiefs. You’ve your own to look after. And I’ve a shrine to keep.”

Fie flinched. Most of her wanted to hare dead south to Dumosa, to burn as many of her teeth as it took to send Rhusana to the next life, to settle Jas on his throne and set off on her roads with Tavin at her side. And doing just that would mean keeping Pa with her that much longer.

But Pa was right. Crows needed every haven shrine they could get, and no band needed two chiefs. In the Jawbone Gulf waited the watchtower of the dead god Little Witness. The keeper there kept track of every shrine to a dead Crow god, and would know which ones sat empty and unused.

When old Crows could no longer travel the roads, they lived out their days in a haven shrine built on the grave of one of their dead gods. That close to a dead god, any Crow could keep the shrine’s stores of teeth alight, hiding it from other castes. A witch like Pa, though, could make a shrine nigh invincible. No doubt he’d be assigned to one they sore needed.

Fie would deliver him there herself, and then leave him behind her for good.

And from the sound of it, she’d do it while Rhusana seemed certain of her victory. Rhusana, who’d promised the Oleander Gentry they could hunt Crows as they pleased once she reigned. Rhusana, whose mere promise of permission had brought more Oleanders down on Fie’s head in the last three moons than Fie had seen in years. Even after she’d delivered the prince to safety.

“What if it gets worse?” she whispered. “What if I’m not enough to look after them?”

“You’ve six Hawks, Fie,” Pa said pointedly. “Two swords. Thousands of Phoenix teeth to burn your way clear. If aught can get through all that, it won’t be a fight meant for a mortal to win.”

That was the heart of her vexation, Fie reckoned. No Crow band in memory had ever had such protection, and still she didn’t feel her Crows were safe. A storm squatted on their horizon. All she could do was try to keep them out of it.

Two moons ago, she’d stood in front of two empty pyres, Hangdog at her side, fresh off cutting an oath with the crown prince. Jasimir had tried to tell her then that the Crows’ only hope of survival was saving him, and Hangdog had sworn it was all a wash.

Now here she was in front of a pyre yet again, but here Hangdog wasn’t after all. The beacons were telling her the last man between the throne and the Oleanders’ queen had died. But there was naught she could do about it now.

The smell of burning flesh began to drift from the pyre. Fie stepped back again, mouth twisting. A warning yowl made her jump. She turned and found Barf, the gray tabby she’d plucked from the royal palace, sprawled on the ground behind her.

If the cat kenned the dire tidings of dead kings and grim roads, she didn’t show it. Instead she chirped and rolled onto her back, paws tucked neat beneath her chin.

Fie knew that trick too well. Pa, however, crouched to rub Barf’s white belly. The tabby promptly latched onto his arm like a snare. He yanked his hand back as Wretch cackled behind them.

“Ought to know better, Cur,” Wretch called. Pa’s name sounded yet strange to Fie’s ear, now that her band called only Fie “chief.” “That beast doesn’t show her belly unless it’s a trap.”

“I do know better,” Pa grumbled. “Just hoped it’d be different this time.”

There was a crinkle as Fie’s fist tightened on The Thousand Conquests. The parchment had turned gummy with sweat. She tossed it onto the pyre, just as she’d promised.

It smoked and caught almost immediately. Fie knew the value of scrolls, the time and effort that Owl scribes put into copying out a work like The Thousand Conquests, how each one was to be prized and protected. Scholar Sharivi had claimed, in a wholly unnecessary foreword, that the tales he’d scrawled within were the unblemished truth. That they captured the history of Sabor, the might of rulers, the wickedness of traitors, the foundations of the nation itself.

Fie doubted with all her heart that Sharivi had captured the foundations of aught but a cowpat, from what she’d read. But in the end, she found he’d given her one scrap of joy: the way The Thousand Conquests was there one moment and naught but smoke in the next.

* * *

The Oleanders came that night after all.

It went as it had the last few weeks: first, Barf sounded the alarm. The cat had no love of Oleander Gentry, not after they’d nearly burned her alive, and since then, she’d yowl and bush her tail out when she caught the rumblings of a dozen or more riders galloping down the road. Even better, she picked up those rumbles at least a full minute ahead of when Fie could.

First the cat howled, then came hoofbeats pounding down the road in the dark, the Crows gathering a bit tighter about the campfire but making no move to flee. The three Hawks on watch would plant themselves between the camp and the road and wait, while the three at rest would sit up, spears within reach.

After that was where Fie had seen the most variation. Once, the baffled gang of Oleanders had offered to assist the Hawks in arresting the Crows. Another time, they had tried to argue with Lakima, then to threaten her, until one rider took a swing at the corporal. Fie had collected the teeth Lakima knocked out of him with particular glee.

Tonight, the Oleanders slowed as they neared the camp, clearly flummoxed by the sight of spears at the ready. Their leader took in the scene from behind a rough rag mask and evidently decided to find some other amusement.

Near two dozen riders trotted past in an awkward, uneasy parade, muttering among themselves and gawking at the guards.

Once, their undyed robes and white powders had frightened Fie. Now she had fire. Now she had steel. Now she had Hawks. The Oleander Gentry looked like children playing dress-up to her, downright silly as they rode away.

She’d always known their kind only picked fights they’d win. She just hadn’t known how it felt when they turned tail and ran.

“Do you think they’re lost?” Khoda jested, leaning on his spear. “Should I offer them directions?”

“Off a cliff, maybe,” Fie muttered, and went back to sleep.

* * *

It took them another day and a half to reach the Jawbone Gulf.

On a clear day, word was you could see all the way out to the tiny island at the most northwestern corner of Sabor, just past Rhunadei. But clear days were rare, even in the summer

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...