- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

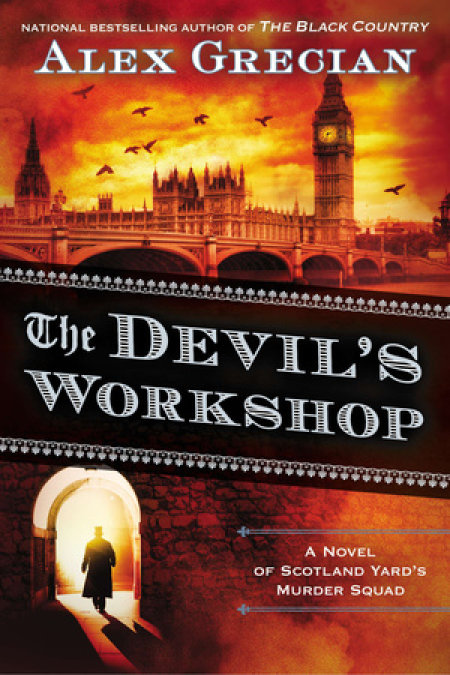

Synopsis

April, 1890. London wakes to the shocking news of a mass prison escape. The Scotland Yard Murder Squad now face a desperate race against time: if they don't re-capture the four convicted murderers before night settles, they'll vanish into the dark alleys of the London's criminal underworld for ever. And in the midst of this mayhem and fear, the city's worst nightmare is realised: Jack the Ripper haunts the streets of London once more…

Release date: May 20, 2014

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Devil's Workshop

Alex Grecian

Copyright © 2014 by Alex Grecian

PROLOGUE

LONDON

LATE APRIL 1890

The white canvas hood covered his nose and eyes and ears, but there was a slit near the bottom of it for his mouth. He could hear muffled sounds, low voices when his captors entered his cell, direct questions when they were spoken close to his ear. When they asked him things, he could feel their hot breath through the canvas, on his cheek and on his scalp, and it raised goose bumps along his arms and the back of his neck, an almost sexual thrill. He could see floating halos of light whenever they brought a lantern into the room, a pale orange haze. They had cut off his long black beard where it curled out from under the edge of the hood. He had been proud of that beard, and the loss of it hurt him almost as much as the abuse his captors heaped on him. He could breathe through his nose, but inhaling caused the canvas to snug up against his face unless he kept his breath shallow. When he breathed through his mouth, through the hole in the canvas, his tongue dried out, and when he tried to swallow he felt an unpleasant clicking sensation at the back of his throat. They never gave him enough water. Food came once a day, barely enough to keep him alive. He couldn’t smell it, could barely taste it. They fed him, poking chunks of bread through the slit in the hood and into his mouth. It was dry and hard, but he choked it down. They spooned broth through the slit and past his lips, spilling it into the rough fabric and dripping it down his naked chest. The heat from it made his skin itch. He still tried to scratch himself, and tried to reach for those men when they came, but his wrists were chained to the wall behind him and his ankles were shackled. The irons bit into him, but the wounds had scabbed over and had bonded with the shackles so that they seemed to be a part of him now. It was this last detail that had convinced him they were never going to let him go. If they tried to remove those shackles, they’d have to rip them out of his skin. He accepted that they meant to keep him here, wherever this was, for the rest of his life. But he didn’t want to die. Even here, in the dark and the silence, he still wanted to live. So he ate their bread and their broth and he sipped at the ladleful of water they gave him twice a day, and he tried not to think about his absent beard.

He didn’t know how long he’d been there. A month? A year? More? The men came every day in shifts, sometimes one at a time, sometimes three or four at once. Always men; never a woman. He had long ago decided that he must be in a small room made of stone, no more than ten feet across and ten feet deep. The ceiling was low, not even six feet, but the shackles prevented him from standing anyway, and so it presented no great hardship for him. Some of the men who came had to stoop as they moved around him. He had learned to recognize the voices of all the men by now. He listened to the way they moved, to the pace of their shoes on the stone. He would know any of them if he met them in the street, even on the darkest of nights. Two of the men were familiar to him from his life before, when he had been a free man. He was sure of it. Something in their voices, something in the way they walked. They had pursued him and he had led them on a merry chase, but in the end he had been careless and they had captured him before he could finish his grand design, his nasty business.

And now they kept him in a box.

He was part of an old story, a story that spanned many centuries and many cultures. He was Loki chained in the Netherworld, Prometheus on the rock. He was a god and these men were mortals. They could hurt him, but they had not killed him yet. Perhaps they could not kill him. He was more than a man. He was an idea and was, therefore, immortal.

Sometimes, in the stillness, he found peace. He couldn’t tell if his eyes were open or closed. The darkness was absolute. He sat without moving, partially suspended by the chains that held him fast. He was a spider, made helpless in its own web, unable to seek prey.

He heard them coming long before they reached his cell. Their hard- soled shoes struck the cobblestones and packed earth, and their footsteps rang out ahead of them. They stopped nearby, out there somewhere in front of him, and there was the faint splintery scrape of metal on metal before a door swung open on rusty hinges and they entered. There were two of them today.

He moved his tongue, tore it free from his teeth. It rasped against the roof of his mouth. He tried to muster some moisture, but there was none. He tried to laugh at the men, but the only sound he could make was a low dry rumble somewhere behind his sternum.

He heard the clunk of the ladle against the inside of a wooden bucket and then felt a welcome splash of water on his chin as the ladle was pressed against the hood and emptied in the general vicinity of his mouth. He gobbled at the air, at the meager stream of water, sucking in as much moisture as he could, but felt most of it dribble away. The canvas hood absorbed some of the water, and it spread upward through the fabric against his face. It felt wonderfully cool.

The ladle was taken away and there was a long moment of silence. He knew what was coming and he tensed. His senses were hyper-vigilant, but he willed his muscles to relax. There was nothing he could do to prevent the coming trauma.

Far in the distance, beyond the confines of the cell, there came the hard, fast rapping of boots on stones. It came nearer and slowed, and he heard a man panting as he entered the cell.

“Exitus probatur.” The man’s voice was low and halting as he gasped for breath.

“Ergo acta probantur,” said another voice, another man.

This was a greeting he had not heard before, and he presumed it must be something formal, a way in which his tormentors identified themselves to one another, or a part of some ritual. This man must have been late, missed some scheduled rendezvous with the others. They rarely spoke when they were near him. How many of them were there? Where did they meet before they paid him their daily visits?

Now he heard the snap of a clasp, the creak of leather on leather. The one with the bag was here. He was the worst of them. Was he the one who had been late? Had he brought the bag or did he always leave it here in the cell?

“Use the iron?”

“No,” one of the men said. “I told you. He didn’t use it, we don’t use it.”

There was a grunt, a faint guttural protest from the other men, but no further argument.

Two metal instruments touched each other, a soft clink as the man took them from the bag. Silence again. Then a hand on the back of his head. The man with the bag grabbed his hair through the hood and yanked his chin up, exposing his throat. He felt metal against the stubble of his old beard and he closed his eyes. Then a blade dug in, deep, but not so deep that he would bleed to death there in the small stone cell. It was a careful cut, and he felt a brief flash of admiration for the skill involved before pain turned the insides of his eyelids red. A moment to let him recover, then the blade sunk in on the other side of his throat. Two cuts. He felt the tickle of blood running down his neck and pooling in the hollow of his collarbone.

They had cycled back to Chapman.

He had learned to recognize the rhythmic pattern of their violence. Every few days, he was being made to experience the pain of one of his victims, at least the victims these men were aware of. They only knew about five of the women, and so they rotated their torture, giving him the wounds of each of those five victims, one after another, then back to the beginning. Again and again. They would hurt him and then go away and, when he had begun to heal, they would return and hurt him again. He took strength from the cycle. Ritual was life.

He knew what came next, but gasped anyway when he felt the scalpel enter his abdomen and slash sideways. He waited for his guts to spill out on the floor, but they didn’t. They never did. The men knew what they were doing. They had cut just deep enough to hurt, to bleed, but not deep enough to kill. They were reenacting the injuries to Annie Chapman’s body, but not going so far as he had. How could they? They didn’t understand the drama. They were only mimics.

Blood ran down his thighs, and he heard it splash on the floor. What terrors would sprout from that blood, he wondered, if it took root in the earth?

His pulse pounded in his ears, and only when it began to settle did he hear the men packing their evil bag and leaving. They swung the door shut again and he heard them lock it. They walked away down the tunnel, leaving him in silence once more.

Only when he was sure they were gone did he finally allow himself to scream. It was a waste of strength and energy, he knew, heard by no one except the rats and worms that surrounded him in the dark. But he screamed anyway. It wasn’t a scream born of pain or helplessness or fear. It was pure anger.

Under the streets of London, Jack the Ripper screamed bloody murder.

1

Two men stood waiting beside three horses in the dark at the side of the railroad tracks. One of the men, the shorter one, moved nervously from foot to foot and blew into his cupped fists, despite the relative warmth of the spring night. The other man stood still and watched southward down the length of the rails.

They had arrived early and had to wait nearly a half hour before they first felt the track vibrate and began to hear a train in the distance, slowly moving closer. And then it was there, only a few yards away from them, huffing along, away from the city’s center. With a shriek of metal on metal, it braked in front of them and a stout man clambered down to greet them.

“Exitus probatur,” he said. The ends are justified.

“Ergo acta probantur,” said one of the waiting men. Therefore the means are justified.

The train’s enormous engine purred and grumbled behind them. An owl hooted. One of the horses snorted. The stout driver coughed and spoke to the other two in a low whisper.

“I’m having another thought about all this,” he said. “It’s too dangerous.”

“Is it empty?”

“What?”

“Is the train empty? Are you the only one on it?”

“Yes, of course. Just me and Willie.”

“Willie?”

“The fireman. He’s in there feeding coal on the fire.”

“We only brought one horse. We didn’t know there would be two of you.”

“It’s fine. We’ll ride together. But I’m trying to tell you we’ve been talking about it, Willie and me have, and we’ve changed our minds.”

“Bit late for that,” the short man said. “You’ve taken our money.”

“You can have it back.”

“You should do as you’re told.”

“I just don’t feel right about it. Willie neither.”

At last the taller man spoke. “The warders have been warned already and they’ve been paid to stay well away from the south wall. Nobody will be hurt except perhaps a prisoner or two.” He used the tip of his cane to point at the driver. “Is it the well-being of convicted murderers that concerns you? The fate of men who are already waiting for execution?”

“Well, no,” the stout man said. “I suppose not, but—”

“Such a man as that is no longer truly a man. His fate has been decided, no? This is what we say.”

“Well, yes, but—”

“Then we’re in agreement. You have ten minutes to convince Willie. Wait until we’ve got it sorted at the back of the train, and then get this thing moving again.”

Without giving the driver a chance to respond, the tall man led his companion down the rails to the last carriage, the guard’s van. He leaned down to peer at the coupling that held it in place. He looked up at the shorter man and smiled, his teeth glinting in the light of the moon. Then he knelt in the dirt and got to work. The other man ran up the line and began to work on another coupling there.

The train was fastened together with loose couplings, three heavy links of chain that allowed the individual carriages to get farther apart and then closer together as they moved, reacting to the speed of the train. The guard’s van was weighted to keep the back end of the train taut, stopping the last few carriages from breaking their couplings and f lying off the track at every sharp curve.

The tall man unfastened the last coupling, freeing the empty guard’s van. The other man sawed halfway through a link in the coupling between two of the four rearmost cars. The birds and insects in the surrounding trees went silent at the sound of the saw as itvoosh-vooshed its way through twisted iron. Weakening the link was probably unnecessary, but the men had agreed to take no chances. Their mission this night was the culmination of months of planning.

When the link was sufficiently damaged, the man stepped away and tossed the saw as far as he could into the trees. He rejoined his companion, and they walked together to the front of the train. The driver shook his head, but didn’t renew his argument. He climbed up into the engine and released the brake and the train began to roll forward. It picked up a little speed, the wheels rolling smoothly over the rails. A moment later, the driver hopped down again. He stumbled forward but caught himself before he fell. He was followed by a thinner man who landed awkwardly, fell forward and rolled into the grass, but stood and nodded to the others to let them know he was unharmed.

The four men stood beside the rails and watched as the driverless train chugged away from them, gaining speed as it disappeared into the darkness. A soft plume of black smoke drifted up across the moon and then dissolved.

The stout driver quietly accepted the reins of a mottled bay. He and his fireman, Willie, heaved themselves up, turned the horse around, and followed the two other men toward the city.

The locomotive rocked and bounced along the tracks, swaying from side to side and picking up speed as the last load of coal in its firebox burned away. The track approached the southwest corner of HM Prison Bridewell’s outer wall, then curved sharply to the east, but there was no driver to slow the engine and ease it around the bend. The train had accelerated to forty miles an hour by the time the prison hove into view and the engine slammed through the curve, dragging ten carriages behind it. The loose couplings between them contracted and then quickly stretched taut as the carriages moved forward and back to accommodate the sudden turn. Seven carriages from the front, the middle link in the chain snapped where it had been weakened. The back of the train tilted, then slammed down onto the rails. A forward wheel jumped the track and, unmoored and empty, the final three carriages left the rails and powered down the embankment toward the prison walls as the front half of the train continued through the curve and away.

Twenty minutes later, a few cautious prisoners left their ruined cells and began to explore. Among them, Griffin waved Napper back and squatted next to the warder’s motionless body. He watched him for a long moment, looking for any sign of life. But there was none. The warder’s head was split open and a large stone from the wall of the prison’s south wing lay nearby, soiled with blood and matted hair. Griffin shook his head and clicked his tongue against his teeth in disappointment. Napper misunderstood, taking the sound as an opening for conversation.

“Serves him right, says I,” Napper said.

“Didn’t ask what you say,” Griffin said. “He wasn’t supposed to be over here at all. The warders were warned.”

“Id’ve kilt ’im myself.”

“Well, the wall saved you the trouble.”

Prisoners were not allowed to speak. The walls of their cells were soundproofed, and when they were given exercise time, they were required to march silently abreast. Isolation was a part of the rehabilitation process. Griffin approved, despite feeling that rehabilitation was an impossible goal for most of the inmates of HM Prison Bridewell.

Griffin pulled the warder’s jacket off. He removed his own bloodstained shirt and draped it over the warder’s body, then put on the warder’s blue jacket. Its sleeves were an inch too short for Griffin’s arms, but it was less conspicuous than his prison uniform, with its pattern of black darts on white canvas. He shrugged his shoulders up and stooped a bit and decided it looked passable in the dim light of the prison corridor. He snugged the warder’s small cap down over his unkempt hair and kept his face to the wall as he walked, leaving the warder’s body in the corner. Napper shut the door of his cell and followed a few yards behind Griffin, keeping to the shadows as best he could.

If it were possible to see Bridewell from above, it would look like the right half of a broken wheel, with four spokes radiating outward from a central hub. The rim of the half wheel was an outer wall that bordered a courtyard surrounding the prison. Each spoke was, in fact, a two-story double corridor, with cells spaced at equal intervals down the length of it. Each of the four spokes was meant to house a different class of criminal, all of them men. There was no exit at the end of any of these spoke-corridors, and a fire four years earlier had killed eleven prisoners, all of them driven by f lames down the inescapable length of that wheel spoke. There had been no public outrage at the news of their deaths. The eleven prisoners had been convicted of murder or rape, and the prison had simply swept out the corridor, buried the remains, and quickly filled the vacant cells. Since the fire and the refurbishment of that spoke of the “wheel,” less attention had been paid to where any particular prisoner was housed, and now murderers were kept with thieves and dippers were kept with male prostitutes. To leave the prison from one of the spokes, one was required to pass down the length of the corridor and through a heavy oaken door, banded with steel and locked from the other side. At that point, on any ordinary day, one gained access to the hub of the wheel and there were several doors to the prison yard from there, provided one was authorized to be moving around outside a cell.

At the moment, however, there were no warders in sight, except the dead man on the floor, and the prison was experiencing a brief bubble of calm that had settled in after the runaway train sheared off the southwest corner of the outer wall, plowed through five cells on the lower level of the south wing, and deposited itself, wheels still spinning, within the prison’s hub, only two feet away from the next wing full of inmates. Rubble and the twisted mass of the train blocked the ruined walls of the cells, except for chinks of light that shone through. A massive cloud of dirt and smoke still swirled about, the light beaming into it from outside, but had slowly begun to settle.

Griffin and Napper moved down the corridor to the far end, their feet sliding and crunching through grit. Griffin removed a chain from around his neck. Three keys dangled from the end of it, and he quickly selected the largest of them. He stuck it in the lock, turned it, and pulled the door open, scraping it against fallen rocks. Inside was a mangled corpse in dart-studded white cloth, only his lower extremities visible atop a fast-spreading pool of blood. Griffin left the cell and went back to the corridor, moved a few feet down, and tried the next door. He was conscious of the time he was taking and concentrated on staying calm. The train’s carriages had sheared through the westernmost wall, beginning at the southern tip, killing everyone in those cells and collapsing the floor above as they went. The prisoners were freed in their last seconds of life. Napper had been the only inmate to survive on that side of the wing.

The prisoners on the other side of the corridor had fared better. Most of the cells on the ground floor were at least partially demolished, but much of the floor above was intact. Griffin could hear men beginning to move about up there, but there was nothing he could do about them. It would take too long to free them. He knew that there was very little time before authorities would arrive to restore order. Griffin eventually found three survivors on the ground floor, three who were on his list, and freed them. He motioned to each of them in turn, and they followed behind him along with Napper. When he had found everyone he could in that wing, Griffin doubled back to the door at the opposite end of the corridor. A man above him on the east side of the corridor began to shout, challenging Griffin to free him. Others took up the chorus, but their voices were muted by a brown cloud of dust, and Griffin didn’t even look at them. He had as many men as he could realistically take with him. All the men he wanted.

He took a deep breath and pushed against the door. It swung open a crack on its iron hinges, and Griffin saw Napper hug the wall. He smiled. At this point, the greatest danger to Napper and the others was not the warders.

The door cracked open and Napper scampered forward, pushed behind Griffin, suddenly brave and anxious to get out of the stifling corridor. Griffin shooed him away and sidled through the narrow opening.

The dimly lit hub was quiet. Without warders and prisoners moving through the space, the main room ahead of him seemed cavernous and long-since deserted. Griffin pulled the door open wider and, when the four other men were through, he shut the door and bolted it. The voices of screaming men in the ruined wing abruptly vanished, closed off by the enormous soundproof door.

Through a pile of loose stones at the base of the south wall of the hub, Griffin could see a wedge-shaped section of a locomotive carriage. If it had traveled through one more wall, it might have hit Griffin’s cell in the next wing and killed him. He took a deep breath and looked around him at the other men.

One of them was tall and bald. He had a nervous air about him and would not meet Griffin’s eyes. The bald man turned and strode away, and Griffin hissed at him to stay with the group. Any one of them who split away was likely to be caught and returned to a cell. The bald man glared at him, or rather at his shoes, but rejoined the ranks, and Griffin motioned for them all to follow. Griffin could hear Napper and the others close behind him as they moved across the big room, navigating around evenly spaced wooden tables and chairs, scarred and blunted by years of use, and through another door at the far end.

He led them through a succession of smaller rooms and down a long corridor that circled the inside of the hub’s outer wall. Above them, a gallery jutted out over the floor where a warder would usually be posted. Griffin wondered again about the dead warder they had encountered. Why had he not been warned?

They passed through another door, and Griffin shut it behind them. They were in a small room with an enclosure in the corner where Griffin remembered changing from his street clothes to the prison uniform. This was where new men were brought into the prison. They were now close to the world outside. Griffin had only been in the prison for two days, yet he was surprised by how much he already missed the outside world. He thought of horses and carriages and umbrellas, he thought of flowers and trees, he thought of women. He looked at the others with him, and he knew that they were thinking of their impending freedom. They were all murderers, all sentenced to death for their crimes. There was a single door and a gate between the four of them and freedom. He wondered what they had planned for the days and nights ahead and concentrated on memorizing their faces so that he could identify them if they were separated later. He knew Napper, and the bald man’s name was Cinderhouse. Of the others, one was tall and gaunt, his limbs and neck stretched long, his face lean and expressionless. He resembled a walking tree. His name, Griffin knew, was Hoffmann. He nodded at Griffin. The other man stayed in the gaunt man’s shadow and scuttled along the wall as if hiding from everyone else in the room. Griffin had seen this smaller prisoner in the exercise yard. Some of the other inmates referred to him as “the Harvest Man,” but Griffin had no idea what his real name might be.

He used the big key to unlock the door ahead of them, and Napper instantly bounded ahead, pushing the others aside in his hurry to get out. Griffin found himself forced against the door- jamb. He scowled at Napper’s back, but held his tongue.

And then they were all outside in the fresh night air. Griffin looked up at a low scud of clouds drifting slowly through the deep dark blue. Beyond the clouds, he could see a scattering of stars and the hazy glow of a full moon. A drop of rain hit his cheek and he let it roll along his skin, savoring the coolness of it. He looked back at the prison, but the damage was out of his line of sight, around the curve of the hub. From here, there was no sign that the wall had come tumbling down.

Napper scampered past again, his head up, staring at those same stars, that same moon, those same clouds. Griffin’s eyes narrowed and his breath quickened. His hands balled into fists, and he heard a low growl that he only gradually realized was coming from himself.

He felt eyes on him. He turned his gaze from the sky to the killers around him and realized that the tall gaunt man and the bald man were staring at him. Where had the Harvest Man gone? And why didn’t he have a proper name? The gaunt man held a finger to his lips. The bald man shook his head slowly from side to side. Griffin nodded, annoyed, and motioned them forward across the dirt yard.

They moved over the grounds and to the gate in the high fence as the clouds opened up above them and it began to rain. The gate was abandoned, no warder in sight. Napper ran past them all and grabbed the bars of the gate in both hands. He pushed and the gate swung open, and they all followed him through to freedom.

Griffin stepped through the open gate into a wide brick plaza and squinted into the unseasonal fog. There was nobody outside the prison waiting for him, nobody in sight in any direction he looked, except the three remaining murderers. The night was silent and empty.

He watched the others disappear separately into the low-lying mist, none of them looking back or at one another. They were simply gone, marked here and there by pale afterimages against the dark sky. He felt a brief moment of panic, but squared his shoulders and made a quick decision. He fished inside the waistband of his trousers, found the hidden pocket sewn in the back, and pulled out a small chunk of blue chalk. He knelt and drew the number four on the bricks outside the prison gate, then an arrow that pointed away from the prison. He stood and filled his lungs with fresh air, decided to follow in the direction Napper had gone across the empty field to his right, and made himself disappear, too.

2

Detective Inspector Walter Day left Regent’s Park Road and picked his way down the steps that led to the tow-path bordering the canal. The moon was bright and full and its light gleamed on the water, but did nothing to illuminate the ivy-covered black rock wall beside him. The soles of his slippers slapped against the stones underfoot.

Day’s wife, Claire, was under the mistaken impression that she hadn’t been sleeping lately. In fact, she slept fitfully in short bursts that she later couldn’t remember. She tossed and turned and snored and f lung her limbs at him, trying to arrange herself comfortably around the mass of her belly. Day often snuck out of bed and went to the parlor, poured himself a brandy, and read until he fell asleep in his big leather chair. Tonight, the moon had beckoned. He had put on his trouser

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...