24 October 1887, Athenaeum Theater, borough of Southwark, London

It took three hours to kill Charlotte Bainbridge.

An egregious amount of time for an exsanguination, he knew. Any slaughter-man worth his salt would have scoffed at anything beyond eight minutes from first slice to last drop. But this instance demanded less of speed and more of precision. And though his hands had known blood, he was not an habitué of the abattoir. He was an artist.

Haloed by gas lamps, Mr. Pretorius continued his work in near silence. The only noise to be heard was the iron creak of the gibbet where a life-size Automaton hung amid overburdened shelves and cabinets full of the ephemera of the stage. If anyone had said to him fifty-odd years ago, when boarding the belly of a boat from Barbados in the afterglow of emancipation, that he would one day find himself in the understage of an English theater, with the fresh body of a dead girl, he would have laughed.

So it beggared belief how only that morning his little shop, nestled back behind the ropes and pulleys and hydraulics of the understage and dedicated to the props and contrivances that dazzled the eye and confounded the senses for the Athenaeum’s productions, had been transformed into a death house worthy of any hospital in the city. Only a few hours had passed since the audience had exited and the theater stilled before his precious workbench was pushed to the wall and in its place a mortuary table appeared. Trays, surgical instruments, and foul-smelling fluids had disordered the orderly chaos of his hammers, levels, wrenches, and wiring. It all seemed impossible, and yet—

He tested the needle’s integrity against the meat of his thumb as his old Nani had taught him and, hovering over her body, threaded the sharp point through the open incision on her neck, lacing the fine silk over and across the wound until the flaps of skin were neatly stitched closed. A faint trickle of fluid escaped over his fingers, but a quick, tight knotting of the silk stanched the leak.

“I have said this before, Pretorius, but it bears repeating. You have one of the finest set of hands in London.” Aurelius Ashe approached the table where Charlotte’s body lay. His soft leather boots barely made a sound on the carpet of damp sawdust on the floor. “These sutures are barely noticeable.”

The great illusionist’s stage vestige had been swept from him but none of the swagger. He stood straight-backed, hands in pockets, with kohl still smudging his dark eyes.

“The best I could do,” Pretorius said, dropping the needle into the tray on the table. “I had hoped to leave her unmarred. If I could have figured out another way—”

“My dear Pretorius, you know that no one ever leaves here unmarred.” Aurelius studied Charlotte’s prone body. Pulling his hand from his pocket, he let his fingers hover over the dead girl’s face, never quite touching her skin but running a hair’s breadth above. Down along her cheek, he traced her jawline until his sharp nails touched down on the stitches at her throat.

With any good magician or thief, hands were the tools of the trade. One hand ready to distract while the other picked the pocket. For Aurelius Ashe, the distraction was built in. Indelibly inked onto the back of his hand was the image of a wheel. Taken from the tarot, this Wheel of Fortune moved along his skin with each motion. Not in the natural way that skin moves over active muscle and tendon but as a wheel over ground. On the wheel spun, until his hand stilled.

Pretorius’s own hands had taken him farther than his skin told him was allowed. Brown, callused, and hard as horn with fingers thick and suited for the labors Aurelius required. The pinkie of each hand was spatulate with nary a nail, an old injury that had left tips flattened, crushed, and absent of feeling. These were not the hands of a magician, and for that he was grateful.

“I warned her, as I did our mutual friend, that she would not be the same. Concerns were dismissed,” Aurelius said, slipping his fingers through her hair. “Look at her, the sleeping lamb. Not a care in the world.”

Pretorius noted the gentleness applied. It might have been a comforting gesture if it was not a precursor to the violence to come. Not to Charlotte, who was well past feeling, but to Aurelius, for whom there was no god to offer a single mercy with this private performance.

“Now, as to your thoughts on there being another way… you know as well I that any alternative would not have been in her best interest. We discussed this and you agreed. Do you no longer trust me on this matter?”

“I might question your methods now and again, my friend, but I’ve not lost my faith in them nor my trust,” Pretorius said. “Even when they make me a murderer.”

“That’s a bit harsh.” Aurelius’s head darted up. “You know I never make anyone do anything. I only offer the means.”

Pretorius shook his graying head with the impishness of a fox at a rabbit warren. “Maybe we should have thought of bringing this to the stage.”

“There are some things in life, Pretorius, that do not need an audience. Not even you. Dim the lights,” Aurelius said as the first wisps of the gray clouded his dark eyes.

Stepping away from the table, Pretorius crossed the shop to where the Automaton hung. Reaching behind the gibbet, he turned the central valve he had installed to lessen the flow of gas to the lamps. The shop fell into soft golden shadow as the hiss dropped to a whisper. It was craven, he knew, to remain at this safer distance, but if this turned out to be the one time that Aurelius failed, well… there was no need to risk them both being taken by this dangerous trick.

The first words of an ancient tongue, fluent to Aurelius but foreign to his own ears, churned the quiet room like a rush of water. Pretorius looked at the Automaton.

“No audience means you too,” he whispered, gently turning the gibbet until the inanimate eyes no longer faced the spectacle at the table. He might have looked the fool for doing so but he was not about to risk one of his creations should the trick go astray.

Few people knew that magic was real. Even practitioners of long standing often dismissed the existence of magic as nothing more than card tricks, distraction, and sleight of hand. Entertainment for pleasure, for money, prestige. After all a magician’s greatest trick is getting you to believe what they themselves often do not. For Pretorius, magic, like faith, was not to be instantly doubted as false, although he was of a mind that preferred what could be seen, touched, and explained by taking something apart and rebuilding it. There was truth in the precision of science, and his understanding of the world came from the tangible not the fantastic.

Magic was not a game to be played lightly. As Aurelius Ashe had shown him, it was only the most daring practitioners who attempted to harness its darkest secrets. Many lost their lives, their sanity, or both in the gamble to understand and to perhaps amass power for themselves. While he had no desire to enter the realm of magic, he no longer questioned the validity of its existence. Too often Aurelius had succeeded in doing the unimaginable. Still, every man had his vulnerabilities, and luck didn’t last forever.

Pretorius chanced a glance back at the table in time to see Aurelius’s shoulders shudder and his strained body lurch over Charlotte. The temperature dropped in the shop like hail. Pretorius’s breath rimed the air, droplets coating his beard, and the impishness that had taken him before passed in the wake of the serious undertaking.

He couldn’t watch his friend’s sacrifice any further. He looked instead at the grate in the ceiling where outside the dull roll of Southwark echoed down through the ventilation ducts. He wished again that he had torn up the letter that had brought the man, who in turn brought the girl, this girl, to their door. The thrum of horses and wheels and the vague shouts of the streets at night. Life!

But those noises soon gave way to a cruel, deathly rattle, and Pretorius whirled around in time to see Aurelius stumbling back from Charlotte. His shirt was sweat-matted to his chest and back, and remnants of a dark fog trailed from the corners of his mouth. The gray that had clouded his eyes retreated and returned to black, hollowed and haunted as the universe. The demon claws had held and slowly the shop warmed again.

Pretorius pulled his watch from his well-worn waistcoat pocket and began to count the seconds.

One—Two—

His eyes shifted from Aurelius, slumped down on the dusty floor utterly drained from the act, back to the table where the dead girl lay. Old Nani’s last words to him before he boarded the boat to England bit at his ear.

‘Do your best to be a free man, but if you must serve another, choose your master wisely.’

Taking a breath, the watch ticked down.

Three—

Slowly Charlotte stirred.

17 October 1887, Ports of London, Southwark

The wind blew from the east the night the ship was first sighted along the south bank of the River Thames.

There were no horns, no whistles, no bells to sound her approach, only two stories of sleek black hull slicing the water like a bat’s wing through the dark.

Giant wrought-iron wheels saddled either side of her, each partially hidden behind a half-moon paddle box painted black, a match to the hull, and sprinkled in silver stars. The wheel’s wooden paddles were sheathed in bright copper that glistened in the spray and splash, each turn a damning rebuff to any who stood in her way.

The nightly sifting of every sharp-eyed Mud Lark on the river halted as she thundered toward port.

“You see anyone?” one boy asked at the river’s edge. He hopped foot-to-foot amid the thick of the stink, hoping to bring relief from the cold swirling around his ankles. The dank bandage wrapped around his left foot offered no relief; the linen only sopped the water, creating a thin barrier between the soft mud and his bare skin. A pair of boots hung around his neck from their laces. The muddy soles bounced off his hollow chest but he didn’t dare leave them on the bank, as they would be gone as quick as the tide. It took losing something precious one time to learn that honor among thieves is a lie.

“Looks like a ghost,” said another as the ship towered past, roiling the low tide mist in her path as either an act of pure entitlement, an honest oversight, or simple disregard for the safety of anyone else on the water. The tall black funnel protruding from the heart of the ship’s body caught the young hungry eyes.

“That there ain’t a ghost, my lads.”

The boys turned toward the approaching creature, whose hulking form draped in thick canvas trousers and a thicker long coat was more bogey than man. His grease-matted hair fell across his pallid skin and into a pair of moon-gray eyes that reflected his subterranean life. He was every bit the imagined monster parents warned their children of on the darkest nights, but the hardened Mud Larks did not flinch at his company.

True, it was rare to see Old Tosher Jim or any of his ilk topside of London trawling as they did in the tunnels beneath, living and often dying away their days in filth. There was, however, one sure lure that would bring these men to the surface, away from the noisome sewers, and that was the promise of copper. And this incoming ship had enough copper on her to fill a tosher’s belly for a year.

An explosive bellow of steam shot high into the sky, painting the night a momentary white.

“And again we are to see our share of devils.” He sat his bull lantern on the bank like a votary amid the shit and rubbed his rough hands together, jostling the treasures in his bulging coat pockets.

The boys eyed the old man. “You saying you know who’s on that ship?”

Tosher Jim ran a grimy hand back through his hair. Flakes of dandruff and dried mud drifted onto his shoulders. “Aye, I do. Demons and dreams is what she brings, which is why I say that you lads are best keeping to the river. Take it from your Old Jim, steer wide and forget seeing that ship or any of those who sail on her.”

“And if we don’t?” asked the boy with the boots dangling at his neck.

The tosher retrieved his lantern from the river’s filth. “What’s your name, boy?”

“Michael Mayhew,” the boy said, with as much firm conviction as the silt sifting between his toes.

“Well, young Michael my lad.” He smiled, clamping his free hand onto Michael’s thin shoulder. “Don’t and be damned.”

In validation of Tosher Jim’s threat, the dark ship woke. Flames flickered in her deckhouses as the gas lamps within sprang to life. Within minutes, much of the lower hull illuminated against the river like a Turner waterscape. MANANNAN was emblazoned across a large brass plate near the tip of the bow.

Lost in the spectacle, few noticed the tide rising. Soon their opportunity to search the shore for nails and scrap would be lost until the next day’s low.

Who could look away, though, when the stars speckling the paddle boxes began to spread across the hull until the random pattern shifted into words:

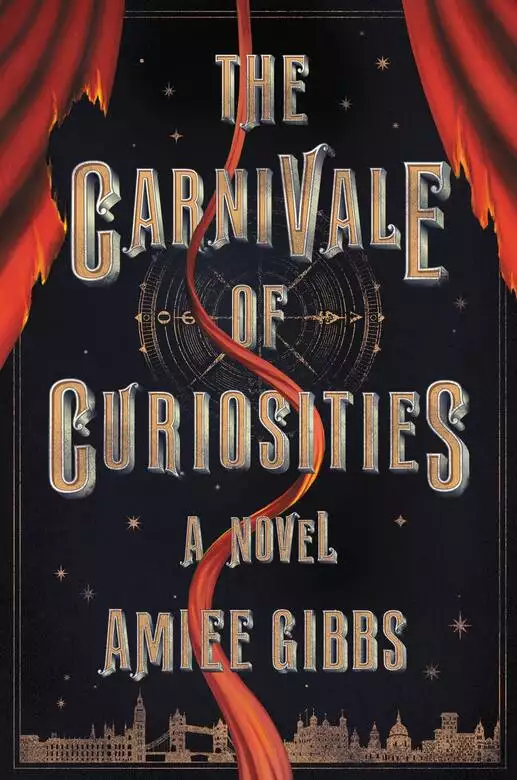

Ashe & Pretorius’s Carnivale of Curiosities

It had to have been a trick of the eye, this moving of stars, and even the sudden presence of a tall figure at the bow did little to assuage this doubt. He stood stock-still with one hand held out over the water. Balanced in his palm were three spheres of light that he flung high into the air. As each rose, the next higher than the first, the spheres exploded in a flash of fire and spark to the delight of the watching Larks.

He heard the children murmur and squeal, but from where he stood the air was so deadened with grease and fog that even following the tails of the flares he could barely see the spires of the bridge, let alone the faces of his audience. A hint of unease, quite untraceable to any reasoned source, nagged at him. Pulling his heavy coat close, he waited, half hoping that his signal would go unanswered, but knowing as sure as the paddles that sloshed the filth-thickened waters that luck was not to be with him.

The tick tick of the watch dangling from his waistcoat pocket counted the minutes until three flares of light shot over Tower Bridge. He followed the stripe of light as the last retort sliced through the darkness with a distant boom. A chill cut through him. No amount of clothing could cure the touch. Nevertheless, he pulled his scarf tighter.

As he hurried back to the deckhouse, a shadow crossed him. It was a dark sliver that danced away as quickly as it had come, far too quick to see the shape of its meaning.

17 October, aboard Manannan

Dear Mr. Ashe, I have in my possession something you might be interested in…

“It never ends,” Aurelius Ashe said, hearing the salon door open. He did not bother raising his eyes from the picture in his hand. “So many offers and every single one the same…”

“Nothing promising then?”

“This one”—Ashe flipped the picture like the third card of a three-card trick—“clearly a fake and not even a particularly good one.” He threw it down, nearly upsetting the pile of neglected letters that teetered on his desk.

“Ever since that damned Mermaid they’ve been crawling out of the woodwork with whatever piecemeal chimera that can be thought of. I ask you, Lucien, do they take me for a repository for every odd bit of claptrap?”

“Can you blame them?” Lucien pulled the damp scarf from his neck and tossed it across the red leather chaise. The stink of the river was a ghost on the wool. “As long as people enjoy seeing the strange there will be those seeking to profit, no matter what form it comes in.” He pressed his hands to the column radiator, wrapping his fingers around the filigreed cast-iron pipes until his skin scorched. A smile crossed his lips as the chill drew from his bones. “Look what it’s done for Barnum.”

“Then let Barnum continue to store the tat away in his American Museum.” Ashe sniffed, dismissing the name of the impresario as he did any other inconvenient thought. “I haven’t the need for humbugs.”

“You never did like him.”

“On the contrary, if anything I find his ambition admirable, and I would never begrudge a man who seeks to put coins into his coffer. It is, however, a matter of taste. I am not above a little deceit, but I do believe in offering authenticity rather than being a purveyor of hoaxes. It cheapens the art, the name, and in my opinion the experience.”

Had it been anyone else words such as these might have been viewed as jealousy, but from the lips of Aurelius Ashe, it was merely the honest observations of a carnival king with whom few would argue.

“Our paths crossed once, you know, Barnum’s and mine. Long before all of this”—he waved his arms—“and I saw his potential as clear as I see you. He has done well for himself, better than I expected with the encouragement given, but I had still hoped for more from him. Who knows, the man does have vision. He might still conjure up something even greater.”

“Not everyone has your skills,” Lucien said.

Ashe leaned back in his chair, his hands folded across his stomach. Tattooed to the back of each was a tarot image. The Wheel of Fortune on the right hand, on the left the Magician, while the wisdom of the world was etched across his handsome features as deep as the arabesques on the wood paneling behind him.

“It is from the thin air and the high hopes of our patrons’ imaginations that I build. If it can be dreamed, Lucien, if it can be believed, then it can be seen and realized.”

“If only for a moment.”

On the corner of the desk, an intricate brass orrery shone under the lamplight. The planets slowly spun in their orbits.

“Sometimes a moment is all one ever gets. Or ever needs.”

Lucien had learned much of the Carnivale’s business from watching Aurelius, who was always astute, often cunning, and without exception fair in his dealings. These were all skills to be learned. But the man seated comfortably behind the big desk held an intangible quiet confidence that would take a lifetime to acquire if he hoped to be half the magician and twice the master.

“You’ve made the announcement?”

“Yes,” Lucien said.

“And?”

“And Pretorius answered. He knows we’re coming in.”

“Good, good, good, good.”

Lucien remained by the radiator, where curious fingers of heat crept up his spine. “How long are we staying in Southwark?”

“In two nights we should run the first show. After that we’ll have to see. I prefer to wait until after November to set course again, perhaps even to the New Year. Avoid the first and the worst of the Atlantic storms. Why?”

Lucien shook his head. “No reason.”

Ashe leaned forward in his chair. The oil lamps bathed the polished rosewood walls in a warm golden glow, gilding his pale skin and firing his dark eyes.

“Something bothering you, Lucien? You’re rather subdued tonight.”

“No, no… I… I had hoped only for a longer stay in Tangiers. The warmth. The sun.” He shrugged. “I’ve never been fond of English winters.”

Ashe’s eyes narrowed. “I taught you to lie better than that,” he said, his broad smile creasing his bearded cheeks.

And he had. It was the first lesson Lucien had learned, though he was not a constant practitioner. Not like the Harlequin, and certainly not like Aurelius himself, who could unspool a fiction quicker than a thread from a bobbin. The only thing he was quicker at was ferreting out the truth.

“Your objections to returning to Southwark are well noted but they do not change the fact that I have business to attend to here. I have neglected London for seven years in deference to you. I’ll not address the troubles that came before that.”

“You usually show more courtesy when prying into my thoughts.”

“When a man is an open book, he had better expect his secrets to be read.” Aurelius sank back in his chair. “Not that your grief is any great secret. You have taken to wearing it like a second skin.” He swept his hand back through his thatch of long dark hair, into which winter was beginning to creep. “My question is, how much longer do you plan to continue this nonsense?”

It wasn’t the cruelty of Aurelius’s dismissal that seared but the casualness. “Nonsense!” Luce shouted. “You call what happened to my mother—” Rage choked him until his eyes burned.

“No, I call your tiresome mourning nonsense. Lucien, if every person decided to avoid a place because they could not put to rest their ghosts then the cities would fall to the rats because there would be no one left to sustain them.”

Aurelius ran his eyes over Luce’s face, hoping to see a chink in the stone. “I am not entertaining this any further. Southwark remains the nearest to a home that we have. Ghosts and all, this is where we began, where we are bound. It is where our theater stands—”

“I’ve no issue with London proper, but there are other stages, Aurelius, other theaters across the city. We could sell out The Royal Albert, Covent Garden. Why limit ourselves to only The Athenaeum?”

“She stands at the Newington Crossroads, which has proven convenient for my purposes. There are some rules even I must follow, nature of the beast and all. Besides, The Athenaeum is an experience unparalleled by any other circus, sideshow, or theatrical act. To speak of another venue diminishes not only us, but also all that Pretorius has created. His life’s blood runs through every inch of iron, oil, and brick in that building.”

The planets of the orrery spun a smooth click that resonated through Luce deeper than Aurelius’s words could reach.

“When you are running the Carnivale, as I hope one day you will once I tire of it, you can then perform anywhere that you choose as you and I do not live by quite the same dictates. Don’t think me callous, Lucien. If it would bring you some semblance of peace by all means lodge here on ship for the duration of our stay. Spend your evenings, your days in Westminster or Piccadilly, but you will be on The Athenaeum’s stage for every performance.”

Luce’s earlier rage, while no longer boiling, still simmered under the skin. “I wouldn’t dare dream of being anywhere else.”

“We are born into places, Lucien. Not of our choosing, but they are the places that never quite leave our bones, no matter how far we run or how much we succeed. For better or worse Southwark, for all that she is and will be, runs through you like the pitch in your veins.”

“And when my time comes for the Carnivale, am I to inherit everything that entails?” Lucien retrieved his scarf from the chaise and wrapped it around his neck.

“That is some years away to be of any concern now. Whether or not you will walk fully in my shoes is yet to be seen,” Aurelius said. “But I have confidence in your abilities. How far they will take you will be determined by how much you are willing to accept and learn. A role played like any other.”

“Only one with real consequences and repercussions that last long after you’ve left the stage.”

“Few of which will be yours,” Aurelius said. He laid his hand on the desk. The robed magician inked on the back held a wand above his head with one hand while the other, empty, pointed to the ground. Only the most observant eye would have caught the figure’s hands change position until the wand pointed at the ground and the other opened to the sky. “As above, so below, Lucien. Where the two meet is where magic resides. All pure fancy until made real.”

“One day, Aurelius, someone is going to come wanting—” Lucien tucked the ends of his scarf into his coat. “I’m afraid to think of what you have already been asked to do and have done.”

“If I were to stop and think every time about the repercussions of something that I had done or intend to do, well, what a dull little world that would be. Besides, we are merely a theatrical troupe, a band of illusionists and players who serve at the audience’s pleasure. Tell me, where is the harm in giving people what they want?”

“You know the cost.”

“Only because I set the price.” Aurelius smiled, but any humor had faded by the time it reached his black eyes.

Lucien left the deckhouse with Aurelius’s words still stinging.

The side-levered engine thumped a steady tattoo in the ship’s belly. The steps thrummed under his feet as he made his way belowdeck.

“Damn!”

“Dita?” he called into the galley. “Y’aright in there?”

“You mean aside from the tea all over the floor?” she muttered, falling to her knees to sweep the leaves into a small neat pile. Her heavy black skirts pooled around her. She favored the somber color nearly as much as the mourning queen herself, but unlike Victoria, Dita preferred a little flair to her underpinnings, as proved by the lace of her red underskirt that peeped out from under the pool of black.

“Better the tea than the milk, eh.”

She jerked her shoulders and stared up at him from beneath a cloud of thick salt-and-pepper curls. Dita du Reve, the Romani Oracle of Budapest by way of Ipswich, if the truth is to be told. Her grandfather was the last member of the family to set foot in Hungary since coming to England, but Aurelius was not one to let a small fact get in the way of better fiction. She was a natural empath and an instant favorite. Her forecasts had increased the company’s fortunes exponentially. If Aurelius was the Father, then Dita was the closest thing to a Mother the company had. She was the comfort when prejudiced tongues inflicted cruelty, and as a seer she was the answer to all that you feared to ask. “Hand me a cloth. Wet it first.”

Lucien passed her the damp towel then slumped down at the table. “Aurelius?” He gestured to the spent leaves.

“He likes a reading when we near port.”

“See anything of interest?”

“What are you on about?” she said, scooping up the leaves.

“Are we going to have a good run? Any promising offers coming Aurelius’s way? Did you see anything?”

“If I had, I wouldn’t be telling you, now, would I? What I see during a reading is shared between the seeker and seer alone. Not for nosy nibs such as yourself.” She tossed the cloth into the sink. “Now, you look as if you could do with a cuppa.”

“Have we something stronger?”

Dita picked up the kettle. He watched her hook the handle over the faucet’s neck and turn on the tap. Water pattered into the metal basin from the rim of the kettle.

“Biscuits? Though I can do up something more substantial. We’ve some ham left or I could do you a ploughman or a cheese and pickle.”

“Tea is enough.”

“Are you sure? You missed supper. Again.” She turned the tap off and removed the kettle, pouring off some of the water into a teapot before setting the pot back to the burner. A small plume of blue flame hissed against the kettle’s steel bottom as she placed it on the stove.

“At this rate, you’ll be wasting away to nothing.” She poured the hot water out of the pot, leaving the china body warm to the touch.

“Dita—”

“It’s not like you, Luce, love, this loss of appetite. You ill?”

He smiled at the warm familiarity of his name. He often wished that Aurelius would be less formal toward him, but some natures weren’t meant to be changed. “I know that you can’t help yourself and bless you for it, but trust me when I say I’m fine.”

“Is that so?” She walked over and took Luce’s face in her hand. There was an unmistakable aura around him. It was an otherness that even among curiosities spoke to an abstraction from the world where the rest resided. Whether on the stage or in passing, it was plain to see why eyes tended to follow him like a procession. Utterly desirable yet decidedly unattainable.

A whisper past twenty-five and surpassing six feet, Luce wore his lean frame like a hand-tailored suit, comfortable, well fitted, and not a stitch out of place. Beneath a thick mop of cinder-black curls, which had never quite been tamed by hand or brush, was a set of fine features that had been etched with the sort of easy charm that guaranteed notice, and it was only by grace that he was mercifully unaware of what his presence commanded in others. He had a broad clear brow and strong jaw that offered a pleasing symmetry and a pleasant open expression with a wide, engaging grin that contradicted the serious turn his thick black brows suggested.

But it was in his eyes that the magic lay. They were a brilliant, burning blue, a glance of which was so piercing as to be endured for only a limited frequency should one have the fortune, or misfortune, to fall under his gaze. That was the reflection of his true gift. Lucien, the Light-Bringer. Lucien, the Lucifer.

“Paler than normal. A week’s growth of beard on your cheek and the puffiness under your eyes says to me that you have not been sleeping. And you have barely eaten a decent meal in three days. Need I say more?”

She released him, but the imprint of her fingers remained. “I’m beginning to think that I’ll need to tie you to that chair and force a meal down your throat. Oh, and, pet, cuss me one more time and I’ll swat you with that there spoon.”

“I didn’t say anything.”

“You were thinking it. Now, are you going to tell me what is troubling you? Or would you prefer I have a look about that pretty head of yours on my own? By your consent or not.”

“Am I not

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved