PROLOGUE

The cellar was, at least, a cool respite from the murderous heat wave afflicting the Black Forest, though it smelled like a crypt and I nearly broke my trick knee on my way down the crumbling steps. There was no railing, and my knee ached the way it always did when rain was due. Ingrid Vogel took the stairs recklessly, though her long white plait and rheumy eyes betrayed that she was at least four decades older than I am. Apparently, she was one of those lucky octogenarians for whom arthritis was something that happened only to other people.

When she flicked on the light, I followed her through the archway into an ancient stone cellar, startled by how old it seemed. The cellar was faded rock, almost cavernous, built with simple buttresses and curved archways, obviously a remnant of a much older structure than the thatched-roof cottage above. What did this place use to be, I wondered absently, surveying the stacks of parcels and canned goods in the corner. Before I accepted my position at the University of North Carolina, I spent fifteen years in Germany—earning my PhD, doing a postdoc, lecturing—but the nonchalant way Europeans used ancient spaces as basements still felt like sacrilege.

“Frau Professorin Eisenberg,” she said, addressing me formally despite my repeated requests to call me Gert. She stood beside an uneven stone that had been removed from the cellar floor, holding an ancient lockbox. I knew from our emails that the codex must be inside. “Hier ist er.”

Three days earlier, Frau Vogel had emailed to tell me about a medieval codex she found in her late mother’s cellar. She said she’d attended a talk I gave in Germany, but I had no memory of meeting her. Her email described what she knew of the manuscript—it was illuminated, written in Middle High German by a woman—and asked if I would be interested in the find. Attached were radiocarbon dating results verifying the manuscript’s age, and an image of a single sample page. The handwritten text was a sinister rhyme about Snow White in an obscure Alemannic dialect; beneath it was a painstakingly decorated illustration of a wicked fairy dancing on a rose. She had blood-red lips, deathly pale skin, and a tangle of black hair.

When Frau Vogel’s email pinged my inbox, I had been sitting in my office, prepping syllabi for the fall semester, trying to ignore two tenured male colleagues who were prattling on about their latest books in the hall. I couldn’t focus. There was a ball of dread in my throat so large, it felt like it was blocking the flow of oxygen. I was scheduled to apply for tenure the following year, and the application process at UNC was brutal. I needed a book under contract, and my study of the treatment of women in medieval German illuminated manuscripts was going nowhere. It was under review at a solid press, but one of my peer reviewers had dismissed its subject matter as “domestic minutiae.” The criticism made me livid. Centuries of sexist scribes had left huge gaps in what we know about the lives of medieval women, and I was trying to do something about it.

The image of the fairy made me gasp, loudly enough that one of my colleagues peeked into my office with a question on his face. I forced a smile, mouthed the words I’m fine, and waited for him to go back to his conversation before I returned my focus to the screen. The colors of the illustration were jewel-toned, bright; the fairy’s expression could only be described as malicious. My heart fluttered with a delicious thrill of excitement. Was I looking at some kind of gothic ancestor to the Snow White folktale as we knew it? The prospect of studying something new—and so different—made me giddy.

I wrote Frau Vogel back immediately, expressing interest. Her reply was a bizarre request for me to describe my personal religious beliefs. Her prying ruffled me, but I got the distinct impression that she was testing me, so I answered carefully. My religion was complicated. I was raised Catholic, but I hadn’t been to church in ages—a fact that, hopefully, Frau Vogel would understand, given my sixty-four hours of graduate credit on the period that brought the Crusades. Whatever her test was, I must have passed, because her next email contained more digital photographs of the manuscript and a request for my assistance reading it. The additional photos were enough to put me on the plane the next day.

Now, crossing the cellar toward Frau Vogel and her lockbox, I felt an eerie shiver of anticipation. My breath caught in my chest, and I thought I sensed a shift in the room’s energy, as if I could feel the drop in air pressure from the coming storm. The sensation alarmed me, until I recognized the rest of the premonitory symptoms of my too-frequent migraines. The lightbulb hanging from the stone ceiling seemed too bright. My vision was blurry. The dizziness I’d blamed on the twisty drive up the mountain had returned. Of course I would get a migraine now, I thought, cursing my luck.

Resolving to take a sumatriptan soon, I peered into the lockbox. Inside was a burnished codex, timeworn. The cover’s leather shimmered faintly around the edges, as if it had been painted centuries ago with gold dust. When I saw how ornate it was, a faint gasp escaped my lips: There was an embossed frame decorated with a diamond pattern, and the interior of each

shape was decorated with intricate swirls. In the center of it all was a huge design that looked like a sigil. A circle writhing with snakes, large-winged birds, and beasts, at once grotesque and beautiful.

The charged feeling in the air intensified, making me dizzier. I blinked, trying to recover some semblance of professional detachment. The migraine, I thought, it’s knocked me off balance. “Entschuldigen Sie,” I said, fumbling in my purse for the bottle of sumatriptan.

Swallowing a pill, I glanced at Frau Vogel, silently asking permission to pick up the codex. She nodded. I picked it up by the edges, trying to get as little oil from my skin on the cover as possible. It was heavy for its size. I could smell the faint musty scent of the leather, feel its age beneath my fingers. I glanced up at my host again, irrationally uncertain about opening the codex, as though she hadn’t asked me here precisely for the purpose of reading it.

An amused smile spread across Frau Vogel’s face, wrinkling the skin around her lips. “Es ist alles gut. It will not bite.”

I opened the book, embarrassed. On the first page was a declaration of truth signed by someone named Haelewise, daughter-of-Hedda. My fingers twitched with the urge to trace her signature, though I knew better than to touch the ink. The use of a parent’s name as a surname would be unusual for a noblewoman, and I had never seen a mother mentioned instead of a father. Who was this peasant woman who could write, who chose to be known only by her maternal lineage?

I took care not to disturb the pigment, touching only the edges of the pages as I turned them. The ink was surprisingly well preserved for the age of the manuscript, as if it hadn’t spent centuries under a stone in a cellar floor. The parchment was thin but still flexible to the touch. What I had surmised from the photographs was true: The manuscript was illuminated as if it were a holy book, though the text itself seemed to be a narrative, interrupted occasionally with recipes and verse and what, during the time in which the book was written, could only have been considered heretical prayers.

As I paused to read one, the static electric aura became so pronounced that the hairs on my arms stood on end. Intense vertigo overtook me, strong enough that I wondered if it was a migraine symptom at all. I smothered the thought, telling myself to focus. I had taken the sumatriptan. The aura would pass soon.

The manuscript was decorated with colorful marginalia, faded red and gold initial letters in the style of Benedictine scribes, though none of the text was Latin. There were masterful illustrations; the images were every bit as detailed as those monks painted on prayer books. But the imagery was so out of character for what one would expect to find in an illuminated manuscript from this period. Some of the illustrations were mundane, a mother and daughter in

a garden, everyday scenes of births and cooking. Others were the stuff of folktales. On one page, a black-haired woman in a bright blue hood extended her hand, as if to offer the reader the gold-dusted apple in her palm. On another, a ghostly woman in blue knelt in a tangled garden, arms outstretched, psychedelic rays of gilded light radiating from her in every direction. I couldn’t help but linger over an image of a beautiful raven-haired young woman lying dead on what appeared to be a stone coffin—her eyes open, her body encased in pale-blue swirls of ice.

“You can read it?” Frau Vogel asked softly. Her voice sounded far away. I had forgotten she was there.

I looked up. Her eyes were fixed on me. “Ja. Das ist Alemannisch. I need time.”

“How long?”

“All day,” I said. “At least.”

She met my gaze for a moment, then nodded at the rocking chairs in the corner. “I’ll be upstairs,” she said, smiling encouragingly. “I want to know everything.”

DECLARATIONThis is a true account of my life.

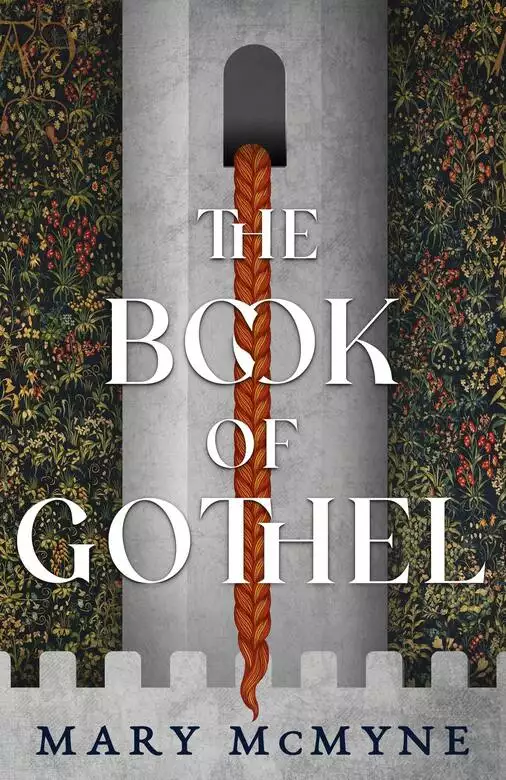

Mother Gothel, they call me. I have become known by the name of this tower. A vine-covered spire stretching into the trees, cobbled together from stone. I have become known for the child I stole, little girl, my pretty. Rapunzel—I named her for her mother’s favorite herb. My garden is legendary: row after row of hellebore and hemlock, yarrow and bloodwort. I have read many a speculum on the natural properties of plants and stones, and I know them all by heart. I know what to do with belladonna, with lungwort and cinquefoil.

I learned the healing arts from a wise woman, the spinning of tales from my mother. I learned nothing from my father, a no-name fisherman. My mother was a midwife. I learned that from her too. Women come to me from all over to hear my stories, to make use of my knowledge of plants. Traipsing in their boots and lonely skirts through the wood, they come, one by one, with their secret sorrows, over the river, across the hills, to the wise woman they hope can heal their ails. After I give them what they seek and take my fee, I spin my stories, sifting through my memories, polishing the facts of my life until they shine like stones. Sometimes they bring my stories back to me, changed by retelling. In this book, under lock and key, I will set down the truth.

In this, the seventy-eighth year of my earthly course, I write my story. A faithful account of my life—heretical though it may be—a chronicle of facts that have since been altered, to correct the lies being repeated as truth. This will be my book of deeds, written from the famous tower of Gothel, where a high wall encloses the florae and herbs. —Haelewise, daughter-of-Hedda The Year of Our Lord 1219

CHAPTER ONE

What a boon it is to have a mother who loves you. A mother who comes to life when you walk into the room, who tells stories at bedtime, who teaches you the names of plants that grow wild in the wood. But it is possible for a mother to love too much, for love to take over her heart like a weed does a garden, to spread its roots and proliferate until nothing else grows. My mother was watchful in the extreme. She suffered three stillbirths before I was born, and she didn’t want to lose me. She tied a keeping string around my wrist when we went to market, and she never let me roam.

There were dangers for me in the market, no doubt. I was born with eyes the color of ravens—no color, no light in my irises—and by the time I was five, I suffered strange fainting spells that made others fear I was possessed. As if that wasn’t enough, when I was old enough to attend births with my mother, rumors spread about my unnatural skill with midwifery. Long before I became her apprentice, I could pinpoint the exact moment when a baby was ready to be born.

To keep me close, my mother told me the kindefresser haunted the market: a she-demon who lured children from the city to drink their blood. Mother said she was a shapeshifter who took the forms of people children knew to trick them into going away with her.

This was before the bishop built the city wall, when travelers still passed freely, selling charms to ward off fevers, arguing about the ills of the Church. The market square was bustling then. You could find men and women in strange robes with skin of every color, selling ivory bangles and gowns made of silk. Mother allowed me to admire their wares, holding my hand tightly. “Stay close,” she said, her eyes searching the stalls. “Don’t let the kindefresser snatch you away!”

The bishop built the wall when I was ten to protect the city from the mist that blew off the forest. The priests called it an “unholy fog” that carried evil and disease. After the wall was built, only holy men and peddlers were allowed to pass through the city gate: monks on pilgrimage, traders of linen and silk, merchants with ox-carts full of dried fish. Mother and I had to stop gathering herbs and hunting in the forest. Father cut down the elms behind our

house, so we had room to grow a kitchen garden. I helped Mother plant the seeds and weave a wicker coop for chickens. Father purchased stones, and the three of us built a wall around the plot to keep dogs out.

Even though the town was enclosed, Mother still wouldn’t let me wander without her, especially around the new moon, when my spells most often plagued me. Whenever I saw children running errands or playing knucklebones behind the minster, an uneasy bitterness filled me. Everyone thought I was younger than I was, because of my small stature and the way my mother coddled me. I suspected the kindefresser was one of her many stories, invented to scare me into staying close. I loved my mother deeply, but I longed to wander. She treated me as if I was one of her poppets, a fragile thing of beads and linen to be sat on a shelf.

Not long after the wall was built, the tailor’s son Matthäus knocked on our door, dark hair shining in the sun, his eyes flashing with merriment. “I brought arrows,” he said. “Can you come out to the grove, teach me to shoot?”

Our mothers had become friends due to my mother’s constant need for scraps of cloth. She made poppets to sell during the cold season, and the two women had spent many an afternoon sorting scraps and gossiping in the tailor’s shop as we played. The week before, Matthäus and I had found an orange kitten. Father would’ve drowned him in a sack, but Matthäus wanted to give him milk. As we sneaked the kitten upstairs to his room, I had racked my brain for something to offer him so we could play again. Mother had taught me everything she knew about how to use a bow. Shooting was one of the few things I was good at.

“Please please please,” I begged my mother.

She looked at me, tight-lipped, and shook her head.

“Mother,” I said. “I need a friend.”

She blinked, sympathetic. “What if you have a spell?”

“We’ll take the back streets. The moon is almost full.”

Mother took a deep breath, emotions warring on her face. “All right,” she sighed finally. “Let me tie back your hair.”

I yelped with joy, though I hated the way she pulled my curls, which in general refused to be tamed and which I had inherited from her. “Thank you!” I said when she was finished, grabbing my quiver and bow and my favorite poppet.

Ten was an odd age for me. I could shoot as well as a grown man but had yet to give up childish things. I still brought the poppet called Gütel that Mother made for me everywhere. A poppet with black hair just like mine, tied back with ribbons. She wore a dress of linen scraps dyed my favorite color, madder-red. Her eyes were two shining black beads.

I

was a quizzical child, a show-me child—a wild thing who had to be dragged to Mass—but I saw a sort of magic in Mother’s poppet-making. Nothing unnatural, mind you. The sort of thing everyone does, like set out food for the Fates or choose a wedding date for good luck. The time she took choosing the right scraps, the words she murmured as she sewed, made that doll alive to me.

On our way out, Mother reminded me to watch for the kindefresser. “Amber eyes, no matter what shape she takes, remember.” She lowered her voice. “You’ll want to warn that boy about your spells.”

I nodded, cheeks flushing with shame, though Matthäus was too polite to ask what my mother had said under her breath. We hurried toward the north gate, past the docks and the other fishermen’s huts. I pulled my hood over my head so the sun wouldn’t bother my eyes. They were sensitive in addition to being black as night. Bright light made my head ache.

The leaves of the linden trees were turning yellow and beginning to fall to the ground. As we stepped into the grove, ravens scattered. The grove was full of beasts the carpenters had trapped when the wall was built. It was common to see a family of hares hopping beneath the lindens. If you were foolish enough to open your hand, a raven would swoop down and steal a pfennic from your palm.

Matthäus showed me the straw-stuffed bird atop a pole that everyone used for archery practice. I sat Gütel at the base of a tree trunk, reaching down to straighten her cloak. My heart soared as I reached for my bow. Here I was, finally outside the hut without Mother. I felt normal, almost. I felt free.

“Did you hear about the queen?” Matthäus asked, pulling his bow back to let the arrow fly. It went wild, missing the trunk to stray into the sunny clearing.

“No,” I called, squinting and shading my eyes as I watched him go after it. Even with the shadow of my hand, looking directly at the sunlight hurt.

He reappeared with the arrow. “King Frederick banished her.”

“How do you know?”

“A courtier told my father while he was getting fitted.”

“Why would the king banish his wife?”

Matthäus shrugged as he handed me the arrow. “The man said she asked too many guests into her garden.”

I squinted at him. “How is that grounds for banishment?” I didn’t understand, then, what the courtier meant.

He shrugged. “You know how harsh they say King Frederick is.”

I nodded. Since his coronation that spring, everyone called him “King Red-Beard” because his chin-hair was supposed to be stained with the blood of his enemies. Even as

young as ten, I understood that men make up reasons to get rid of women they find disagreeable. “I bet it’s because she hasn’t given him a son.”

He thought about this. “You’re probably right.”

I strung my bow, deep in thought. After the coronation, the now-banished queen had visited with the princess, and Mother had taken me to see the parade. I remembered the pale, black-haired girl who sat with her mother on a white horse, still a child, though her brave expression made her seem older. Her eyes were a pretty hazel with golden flecks. “Did the queen take Princess Frederika with her?”

Matthäus shook his head. “King Frederick wouldn’t let her.”

I imagined how awful it would be to have my mother banished from my home. Where my mother was protective, my father was cold and controlling. A house without Mother would be a house without love.

I forced myself to concentrate on my shot.

When the arrow pierced the trunk, Matthäus sucked in his breath. At first I thought he was reacting to my aim. Then I saw he was looking at the tree where Gütel sat. A giant raven with bright black hackles was bent over her.

I charged at the bird. “Shoo! Get away from her!”

The bird ignored me until I was right beside it, when it looked up at me with amber eyes. Kraek, it said, shaking its head, as it dropped Gütel on the ground. It kept something in its beak, something glittering and black, which flashed as it took off.

On the left side of Gütel’s face, the thread was loose. The wool had come out. The raven had plucked out her eye.

A cry leapt from my throat. I fled from the grove, clutching Gütel to my chest. The market square blurred as I ran past. The tanner called out: “Haelewise, what’s wrong?”

I wanted my mother and no one else.

The crooked door of our hut was open. Mother stood in the entryway, sewing, a needle between her lips. She had been waiting for me to come home.

“Look!” I shouted, rushing toward her, holding my poppet up.

Mother set down the poppet she was sewing. “What happened?”

As I raged about what the bird had done, Father walked up, smelling of the day’s catch. He listened for a while without speaking, his face stern, then went inside. We followed him to the table. “Its eyes,” I sobbed, sliding onto the bench. “They were amber, like the kindefresser—”

My parents’ eyes met, and something passed between them I didn’t understand.

Overcome by a telltale shiver, I braced myself, knowing what would happen next. Twice a month or so—if I was unlucky, more—I had one of my fainting spells. They always started the

same way. Chills bloomed all over my skin, and the air went taut. I felt a pull from the next world—

The room swayed. My heart raced. I grasped the tabletop, afraid I would hit my head when I fell. And then I was gone. Not my body, but my soul, my ability to watch the world.

The next thing I knew, I was lying on the floor. Head aching, hands and feet numb. My mouth tasted of blood. Shame filled me, the awful not-knowing that always plagued me after a swoon.

My parents were arguing. “You haven’t been to see her,” Father was saying.

“No,” Mother hissed. “I gave you my word!”

What were they talking about? “See who?” I asked.

“You’re awake,” Mother said with a tight smile, a panicked edge to her voice. At the time, I thought she was upset about my swoon. My spells always rattled her.

My father stared me down. “One of her clients is a heretic. I told your mother to stop seeing her.”

My gut told me he was lying, but contradicting him never went well. “How long was I out?”

“A minute,” Father said. “Maybe two.”

“My hands are still numb,” I said, unable to keep the fear out of my voice. The feeling usually came back to my extremities by this point.

Mother pulled me close, shushing me. I breathed in her smell, the soothing scent of anise and earth.

“Damn it, Hedda,” Father said. “We’ve done this your way long enough.”

Mother stiffened. As far back as I could remember, she had been in charge of finding a cure for my spells. Father had wanted to take me to the abbey for years, but Mother outright refused. Her goddess dwelt in things, in the hidden powers of root and leaf, she told me when Father was out. Mother had brought home a hundred remedies for my spells: bubbling elixirs, occult powders wrapped in bitter leaves, thick brews that burned my throat.

The story went that my grandmother, whom I hardly remembered, suffered the same swoons. Supposedly, hers were so bad that she bit off the tip of her tongue as a child, but she found a cure for them late in life. Unfortunately, Mother had no idea what that cure was, because my grandmother died before I suffered my first swoon. Mother had been searching for that cure ever since. As a midwife she knew all the local herbalists. Before the wall was built, we had seen wise women and wortcunners, sorceresses who spoke in ancient tongues, the alchemist who sought to turn lead into gold. The remedies tasted terrible, but they sometimes kept my spells away for a month. We had never tried holy healers before.

I hated the emptiness I felt in my father’s church when he dragged me to Mass, while my

mother’s secret offerings actually made me feel something. But that day, as my parents argued, it occurred to me that the learned men in the abbey might be able to provide relief that Mother’s healers couldn’t.

My parents fought that night for hours, their white-hot words rising loud enough for me to hear. Father kept going on about the demon he thought possessed me, the threat it meant to our livelihood, the stoning I would face if I got blamed for the wrong thing. Mother said these spells ran in her family, and how could he say I was possessed? She said he’d promised, after everything she gave up, to leave her in charge of this one thing.

The next morning, Mother woke me, defeated. We were going to the abbey. My eagerness to try something new felt like a betrayal. I tried to hide it for her sake.

It was barely light out as we walked to the dock behind our hut. As we pushed our boat into the lake, the guard in the bay tower recognized my father and waved us through the pike wall. Our boat rocked on the water, and Father sang a sailing hymn:

“Lord God, ruler of all, keep safe

this wreck of wood on the waves.”

He rowed us across the lake, giving a wide berth to the northern shoreline, where the mist the priests called “unholy” cloaked the trees. “God’s teeth,” Mother said. “How many times do I have to tell you? The mist won’t hurt us. I grew up in those woods!”

She never agreed with the priests about anything.

Pulling our boat ashore an hour later, we approached the stone wall that surrounded the abbey. Elderly and thin with a long white beard and mustache, a kind-looking monk unlocked the gate. He stood between us and the monastery, scratching at the neckline of his tunic, as Father explained why we had come. I couldn’t help but notice the fleas he kept squelching beneath his fingers as he listened to my father describe my spells. Why didn’t he scatter horsemint over the floor, I wondered, or coat his flesh with rue?

Mother must have wondered the same. “Don’t you have an herb garden?”

The monk shook his head, explaining that their gardener died last winter, nodding for Father to finish his description of my spells.

“Something unnatural settles over her,” he told the monk, his voice rising. “Then she falls into a kind of trance.”

The monk watched me closely, his gaze lingering on my eyes. “Do you suspect a demon?”

Father nodded.

“Our abbot could cast it out,” the monk offered. “For a fee.”

Something

fluttered in my heart. How I wanted this to work.

Father offered the monk a handful of holpfennige. The monk counted them and let us in, shutting the heavy gate behind us.

Mother frowned as we followed the monk across the grounds. “Don’t be afraid,” she whispered to me. “There is no demon in you.”

Through a huge wooden door, the monk led us into the main chamber of the minster, a long room with an altar on the far end. Along the aisle, candles flickered below murals. Our footsteps echoed. When we reached the baptismal font, the monk told me to take off my clothes.

Father reached for my hand and squeezed it. He met my eyes, his expression kind. My heart almost burst. It’d been so long since he looked at me that way. For years, he’d seemed to blame me for the demon he thought possessed me, as if some weakness, some flaw in my character had invited it in. If this works, I thought, he’ll look at me that way all the time. I’ll be able to play knucklebones with the other children.

I stripped off my boots and dress. Soon enough I was barefoot in my shift, hopping from foot to foot on the freezing stones. Six feet wide, the basin was huge with graven images of St. Mary and the apostles. I bent over the edge and saw my reflection in the holy water: my pale skin, the vague dark holes of my eyes, the wild black curls that had come loose from my braids as we sailed. The basin was deep enough that the water would rise to my chest, the water perfectly clear.

When the abbot arrived, he laid his hands on me and said something in the language of clergymen. My heart soared with a desperate hope. The abbot wet his hand and smeared the sign of the cross on my forehead. His finger was ice cold. When nothing happened, the abbot repeated the words again, making the sign of the cross in the air. I held my breath, waiting for something to happen, but there was only the chilly air of the minster, the cold stones under my toes.

The holy water glittered, calling me. I couldn’t wait any longer. I wriggled out from under the monk’s hands and climbed into the basin.

“Haelewise!” my father bellowed.

The cold water stung my legs, my belly, my arms. As I plunged underwater, it occurred to me that if there was a demon inside me, it might hurt to cast it out. The silence of the church was replaced by the roar of water on my eardrums. The water was like liquid ice. Holy of holies, I thought, opening my mouth in a soundless scream. How could the spirit of God live in water so cold?

When I burst out, gasping, the abbot was speaking in the language of priests.

“What do you think you’re doing?” my father yelled.

Finishing

his prayer, the abbot tried to calm him. “The Holy Spirit compelled her—”

I clambered out of the basin, wondering if the abbot was right. Water rolled down my face in an icy sheet. Hair streamed down my back. I stood up, flinging water all over the floor. My teeth chattered. Mother fluttered around me, helping me wring out my hair and shift, trying to dry me with her skirt.

Father watched while I shivered and pulled on my dress. He looked at the abbot, then Mother, his brow furrowed. “How do you feel?”

I made myself still, considering. Wet and cold, I thought, but no different. Either there had been no demon, or I couldn’t tell that it had left. The realization stung. I thought of all the remedies we’d tried so far, the foul-tasting potions, the sour meatcakes and bitter herbs. Who knew what they’d try next?

I met their eyes, making my own grow wide. Then I knelt in my puddle on the stones, making the sign of the cross. “Blessed Mother of God,” I said. “I am cured.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved