AMELIA IN THE ATTIC

Amelia discovered the old book lying in a dark corner of her grandmother’s otherwise empty attic. Its paper jacket was missing—the cloth cover a faded red, almost pink. Embossed in silver on its side was a long title that appeared blurry in the dim light. Amelia was struck, however, by the bright white sticker at the bottom of the spine. Someone had typed numbers on it and adhered clear tape to keep it from falling off. She recognized the numbers. Dewey decimals. When Amelia flipped open the cover, she found a paper pocket glued inside, a blue card sticking crookedly out of it. Each line on the card had been marked with purple stamps—days, months, years—going back decades.

What was a random old library book doing up here?

Her grandmother had not resided in this house for a long time, and Amelia missed her with all her heart. If the last due date stamped on the card was correct, Grandmother would owe the library a hefty sum, unless library fines disappeared when youdisappeared.

Amelia held the book up to the bulb at the top of the steep steps. The title on the spine glinted again in the light—clearer now. Amelia looked closer.

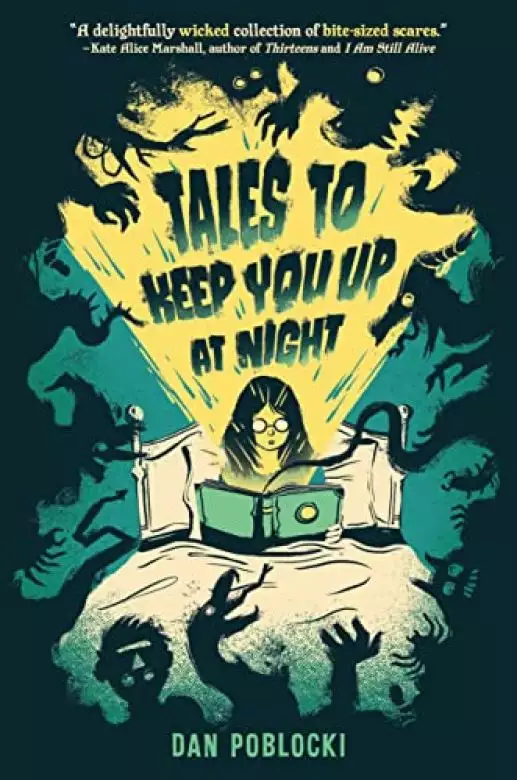

Tales to Keep You Up at Night.

The title was familiar somehow.

A shiver passed through her.

Grandmother had been interested in science and history and memoirs of writers and artists. Scary stories? Not so much. Amelia wondered if Grandmother had left this book up here on purpose.

When she turned to the steps, there was a skinny silhouette staring up from below. Amelia flinched, then blushed. It was Winter—her little brother. She hadn’t recognized him at first because yesterday, Mom had shaved his head after he’d wiggled during a haircut and her scissors slipped.

Amelia had come up to the attic in the first place partly because Win had been pestering her. Recently, he had lost both of his front teeth and had somehow taught himself a shrieking type of whistle that he alone thought was hilarious.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“None of your business,” she answered, brushing past him, keeping the book hidden at her hip.

“Want to play a game?”

“I want to be alone.”

“But I’m boo-oored,” Win whined.

“You could help Mom and Mama with Grandmother’s things.”

“Never mind!” he yelled, and took off running down the hallway.

In the ancient house, his every footfall felt like an earthquake. She shut her eyes and let out a long breath. Winter had only been a piece of the reason she’d sought out the attic. The night before, Amelia had dreamed she met with Grandmother up there. She couldn’t remember much of what happened in the dream. Only bits and slices. But she did remember the dream feeling intense enough that it made her wish to come up and explore.

Was that why the book felt familiar? Had she seen it in the dream?

Downstairs in the foyer, cardboard boxes lined the walls. Amelia’s mom was placing paper-wrapped parcels into one of them, and her mama was in the kitchen, pulling dishes off the shelves and lining them up on the countertop.

“What have you got there?” Mom asked.

“An old library book.” An idea struck Amelia. A way to escape her brother for the afternoon. Keeping her voice low so Win couldn’t hear, she added, “I’m going to go return it.”

“Good idea, sweetheart,” Mom answered distractedly. Amelia’s family had been at Grandmother’s old house all weekend, preparing for its sale. Her mothers were both running on fumes. “The library is just down the street.”

“I know where.”

“Take Win . . .”

Amelia opened the front door and slipped outside, pretending to not hear. A brisk breeze mussed her long hair. She zipped up her green canvas jacket, clasping the faded hardcover to her chest.

“Look both ways!” Mama called out from down the hall.

“I will!” Amelia promised.

The door swung shut as Win peeked from the top of the stairs.

Down the sidewalk.

Around the corner.

Amelia skipped over the cracks in the concrete, concerned slightly about that old rhyme and her mothers’ backs. You know the one. Then she paused and considered what might happen if she decided to not be so careful.

Amelia was hiding a secret anger, something she hadn’t even shared with her best friends, Scotty and Georgia. She hated that Mom and Mama were clearing out Grandmother’s house, that they were going to sell it. What if Grandmother came back a year after she’d disappeared to find the place empty, her memories discarded? Wouldn’t that only make the time she’d been away from everyone who loved her even harder? Amelia wouldn’t share her frustration with her mothers. Whenever they came to a decision, they stuck with it, no matter what anyone else said, especially she and Winter.

The question of Grandmother’s whereabouts had haunted the family since she’d gone missing. One year earlier, Grandmother was supposed to have arrived for lunch at Amelia’s family’s home, a few towns over, but she’d never shown up. When her mothers went looking for Grandmother, they found her car in the driveway and her house in perfect condition. But there was no sign of her and no clues to where she had gone. The police visited over and over, asking a bunch of questions that the mothers kept from the kids. Amelia begged to know what they’d thought was going on.

Mama and Mom had told Amelia and Winter that Grandmother might have been secretly struggling with a health issue. Dementia, they called it. They’d explained that as certain people grew older, sometimes they became confused. Their brains got sick. Betrayed them. Their memories failed. Sometimes they couldn’t recognize loved ones. If they weren’t under proper care, sometimes they wandered off.

Mama and Mom were certain dementia was the answer. But Amelia wasn’t so sure. Shouldn’t there have been some kind of a clue that Grandmother had been ill? Grandmother had known who Amelia was during a visit the week before the disappearance, and her memory had been perfect. She could recall events from her childhood as if they’d occurred only yesterday. As far as Amelia knew, Grandmother hadn’t once gotten lost walking, shopping, hiking, or driving to pick up her grandkids for an overnight.

The scary thing, they said, was that in Grandmother’s town, there was a creek whose banks rose high during storms. Sometimes, the muddy water rushed ferociously, carrying away fallen branches and bug-eaten tree trunks. Things that sometimes never turned up again.

The search had been extensive. There’d been MISSING posters attached to telephone poles and hung in store windows. Grandmother’s photograph even appeared on the local news. The photo they used was one in which Amelia had also appeared. In it, the two were hugging, their wide smiles crinkling the corners of their eyes. When they showed it on TV, they’d cropped Amelia out, which hurt.

It made her feel like they’d cut off a piece of her body.

Amelia’s anger had sparked a couple months ago, when she’d overheard her mothers speaking late one night after lights out. Mama had been crying in the living room, and Mom was trying to comfort her. They’d said things like, I’m tired of this . . . Want it to be over . . . Just like my father . . . Time to move on . . . Not coming back . . . That night they’d made the decision to sell Grandmother’s house. Having strained to listen until the mothers fell asleep, Amelia lay in bed, trying to control her ragged breath, staring at the ceiling until the sun came up.

Part of wanting to take the book back to the library had been to escape the slow packing up of Grandmother’s life.

Head held high, she walked by the grocery store and the lunch place and the hardware store and the Victorian inn that reminded her of the house in that movie about the family of witches who’d been cursed by an ancient ancestor. The one where the women would leap off the roof every Halloween and float gently to the ground. In the town where Grandmother had lived, many of the buildings were partially covered in creeping ivy, and at this time of year, their leaves always turned a vibrant red and flickered gently in the wind as if to say Watch out. Amelia thought she heard Winter whistling. She winced and turned to look for him. When the sound came again, she realized it was only a bird.

One strange thing no one ever wished to discuss was that Grandfather had gone missing a decade prior, in a similar manner. Just one day, gone. Amelia had been a baby, so she didn’t remember. Back then, no one had wanted to admit that Grandfather had just run off. They’d said he was not that type of man. What type was that? Amelia often wondered.

Just like my father, Mama had said. Had she been talking about the raging creek waters? Dementia? Both? Or maybe she’d meant something completely different . . .

Something she was keeping secret . . .

Amelia comforted herself by thinking that maybe Grandmother had gone looking for Grandfather.

Maybe they were together now. Safe and sound.

Not dead. Neither of them.

Amelia refused to believe that.

A sign for the library stood beside the road. A lush green lawn rolled out before a stark white building. From here, the library looked like a small cottage. A path of stones led across the yard from the sidewalk, each one sunk deep into the grass, as if the earth were trying to devour them. Amelia hopped from stone to stone imagining that the grass was lava and if she were to trip, the earth would devour her too. She caught herself and glanced around to see if anyone was watching. Don’t, she scolded. How would she ever join the yearbook crew next year if the kids at school mocked her for doing nonsense like this?

Grow up, Amelia . . .

Opening the library’s skinny door, she realized that the building appeared to be bigger on the inside than had been noticeable from the street. Beyond the front desk, several doorways opened onto rooms filled with endless shelves stuffed with books, a long straight corridor leading to a room at the back, and two sets of stairs, one of which went up to a second floor while the other descended into shadow. Amelia felt an urge to wander, to pluck a book from a shelf, to sit and read for a good long while—long enough to forget about what Mom and Mama were doing up at the house. Was it a good idea? Her mothers would be busy for another few hours at least, and the longer Amelia kept her distance, the less likely she’d be to snap at Winter for some dumb thing or another.

At the desk, a thin woman with thick round glasses glanced up. Her black hair was streaked with gray and pulled into a short ponytail. She wore a gauzy brown dress that looked like it had been constructed from the faded floral wallpaper in Grandmother’s powder room off the kitchen. A plastic card hung from a black lanyard around her neck. It read: Mrs. Bowen, Librarian. The woman’s age seemed slippery. She might have been thirty. She might have been fifty.

Amelia approached, holding out the library book. “Excuse me,” she said. The librarian’s suspicious eyes were enormous behind those lenses. “I found this in my grandmother’s attic.” Amelia laid it on the desk. “It was due a long time ago.”

The librarian picked up the book and looked at the spine. She opened the cover and saw the card in the paper pocket. “A long time ago indeed,” she said, puzzled. Glancing at Amelia, she asked, “And who is your grandmother?”

“Susannah Turner.” Speaking the name aloud, even at a whisper, made Amelia all tingly, as if it were a spell that might bring her back. She made a mental note to do it more often.

The librarian sighed. “I’m so sorry for your loss, honey. Oh, how we miss her here.”

Amelia flinched. What loss? she wanted to say. “That’s okay,” she replied instead. “She’s been gone for over a year now.” The worried look on the librarian’s face made her wish she’d kept that to herself, and yet, there was something satisfying about making an adult uncomfortable. “My moms are packing up the old house. Time to sell, I guess. I wish we could move in. Keep it for her in case she . . .” The librarian’s eyes widened. This was the wrong direction to take, Amelia realized. She backtracked, “It’s just, the house is so big. So much to explore.”

The librarian smiled. There. Better. Grown-ups loved hearing about the curiosity of kids. “I remember. Your grandmother invited me to quite a few dinner parties. Such a lovely lady,” the woman finished, as if Amelia hadn’t said a word about what may or may not have been her grandmother’s tragic ending. Amelia chewed at her lip. This was a hard part—the listening as other people made judgments and drew their own conclusions.

Sudden sadness brushed softly against the inside of Amelia’s skull. She focused on the book again in case some of that emotion tried to find its way out. “I don’t have any money to pay a fine. I just wanted you to have it back.”

The librarian shook her head. “Well, that’s very nice, dear, but your grandmother’s book isn’t from our library.”

Amelia was confused. “Are you sure? ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved