- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

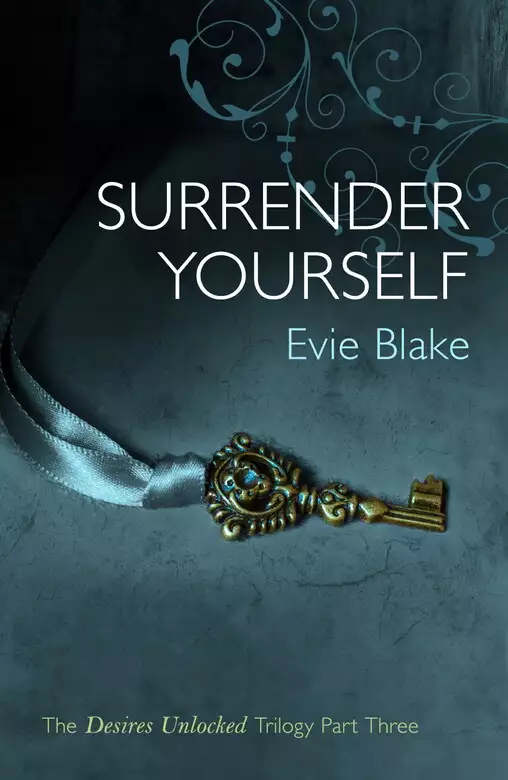

For fans of FIFTY SHADES OF GREY and BARED TO YOU comes the emotionally charged final instalment in the erotic and addictive DESIRES UNLOCKED trilogy. Valentina Rosselli is heartbroken - she has lost Theo, her true love, seemingly forever. Yet, with the help of good friend Leonardo, Valentina gradually rediscovers her liberated sexual self, unlocking her deepest erotic desires and reaching a level of passion she'd never thought possible. And then a shock from the past sends her reeling... In Berlin in 1984, Tina Rosselli risks everything for a steamy, highly charged romance with a charismatic young cellist. Their brief but explosive affair will affect Tina for the rest of her life. As the stories of the two women converge in the trilogy's thrilling and intensely passionate conclusion, both must surrender themselves: to desire, and to love.

Release date: January 30, 2014

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 418

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Surrender Yourself

Evie Blake

Valentina’s hand is in hers. She squeezes it tight. Her daughter’s tiny, cold palm is cooling her hot hand, for Tina is sweating despite the fact it is a bitter day in mid-November. Anticipation courses through her body, heating her from within, making her skin damp, as if she and Valentina are melted into each other. They are as one as they weave through the crowd, Tina scanning it for his face among them. It may have been five years since she last saw Karel but she will never forget his shocking beauty. She is sure she will spot him.

Now this moment has come, finally, she cannot bear to wait one second longer. She sees the East Berliners pouring through the Borholmerstrasse border crossing, and she is sure he will be among them. For had they not promised each other? If the wall came down, no matter when, no matter what, she would be waiting for him. She had said she would be at the first crossing that opened, five days after it opened, at midday. She glances at her watch. It is now five minutes to twelve; in a few minutes Valentina will meet her father.

The last few days have been surreal. She will never forget the moment, as she sat down to watch the evening news, that she saw the interview with the journalist from ANSA. It was a day like any other: packed with work and mothering. She had done a shoot in the morning for Elle magazine, and in the afternoon she had taken Valentina to the park, where she had pushed her in the swings before it had got too cold. She had bought some food on the way home, and stopped to chat to her neighbour outside the apartment. She had called up her son, Mattia, in America to talk to him while her tomato sauce was simmering in the pot and Valentina was drawing pictures with her crayons at the table in the sitting room. She was such an easy child, never demanding her attention.

She said goodbye to Mattia, took the sauce off the stove and had just settled into a chair, staring aimlessly at the television while sipping on her pre-dinner glass of wine, when the programme cut to an interview with East German Politburo member, Gunter Schabowski. A journalist was excitedly asking when exactly the new regulations for free passage by way of all border transit points from East to West Germany and to West Berlin would come into effect. Schabowski’s words in response were still spinning inside her head:

If my information is correct, to the best of my knowledge, immediately.

She had dropped her glass on the floor and it smashed to pieces, spraying red wine all over the carpet, a stain she was never able to remove.

Immediately.

She jumped up from the couch clasping her hands, letting out a small cry so that Valentina looked up from her drawing in surprise. The Berlin Wall was coming down. She had been right. She had told Karel to hope and now he would finally be free. Nothing in the world would stop her from being at that border crossing in five days’ time. It was not because she loved Karel any more. Surely by now he was with another woman? And that was fine; she had Phil. It was not for herself she was going, but for her daughter. This was Valentina’s one and only chance to meet her real father.

‘I’m cold, Mama.’ Valentina is shivering next to her.

‘Not long now, darling,’ she says to her.

‘But why are we here?’ her daughter whines. ‘I want to go home.’

She doesn’t want to tell Valentina about Karel until she sees him. She couldn’t bear to confuse her unless absolutely necessary. She needs to know that Karel still wants to know them first.

She moves right up to the barricade, watches the East Berliners as they walk across the bridge in their throngs. Most are obviously just crossing for the day, to have a look at the other side, before going back home again. But some are going for good, staggering under big cases, pushing bikes with packages strapped on the back, or crawling through in laden Trabants.

She waits and watches as the minutes tick by. By half past twelve she begins to doubt; by one o’clock Valentina is so cold her teeth are chattering. What can she do? Maybe he got held up. If she leaves now, he could come and they would miss him. She looks around her and spies a stall selling hot drinks and pretzels.

They shiver as Tina gives Valentina a sip of her hot chocolate, raising it to the child’s blue lips. Valentina is so cold that she has stopped complaining. Instead she is tugging at her mother’s sleeve every now and again, but Tina cannot take her eyes off the crossing. She cannot risk missing him. The hours tick by. East Berliners come through: people cheering as they cross over, others crying, cars beeping, jubilation and emotional outpourings. Families are reunited, hugging and crying, and still she waits for Karel. She begs him to come. Yet the crowd keeps on flowing across the bridge and he is not among them. She glances at her watch and to her dismay it is three already. She had been so certain that he would be here. Her situation begins to dawn on her.

When Phil had got home late that night, after the announcement about the Berlin Wall on the news, she couldn’t wait to tell him.

‘Did you hear?’ she said, charging into the hall to greet him before he had even taken his coat off.

‘What?’ He looked grey in the face, and terribly tired. She felt a stab of concern for him. ‘The Berlin Wall . . . it’s over.’

‘Really?’ His eyes lit up, and he walked over to the television and turned it on. There were images on the screen of East Berliners bursting through the border at Borholmerstrasse, and walking across the Bösebrücke Bridge.

‘This is amazing,’ he said. ‘We are watching history unfold.’

She put a hand on his arm, and he turned to look at her.

‘Let’s go to Berlin,’ she said.

‘What? Now? To watch the Wall come down?’

‘No, I mean to live for a while. You said we should get out of Italy . . . and, well, now the border is open . . .’ She nodded over at Valentina. ‘I can bring her to meet him.’

Phil looked at her incredulously. ‘You’re not serious, Tina?’

‘Of course I am serious,’ she said. ‘I promised Karel I would be there, five days after the borders opened, with Valentina.’

‘But she doesn’t know him, Tina; as far as she is concerned, I am her father.’

‘But you are not her father, Phil. He is. I have to take her to see him. It’s not right.’

Phil had looked hurt. ‘You know I love her,’ he said.

‘I’m sorry; I know that,’ she said, realising she sounded harsh. ‘And you are a brilliant father, but don’t you see I promised Karel I would bring Valentina to him . . . ?’ she said, softening her voice.

‘Can’t he come here?’

‘He won’t . . . because of you. I know he won’t.’

‘This is madness, Tina. How will you ever find him? It will be like finding a needle in a haystack.’

‘We have an arrangement . . . We promised each other.’

‘How romantic,’ Phil said, sarcastically.

‘Phil, I want you to come too. All of us . . . to be together.’

He shook his head. ‘No way. If you want to go and meet this young gigolo of yours, then go ahead, but I am not going to share you with anyone any more.’

‘What do you mean, “any more”?’

He gave her a cold look but said nothing.

She was confused by his behaviour. This wasn’t her Phil, who was usually so unpossessive and easy-going.

‘Well, I have to go, Phil, for Valentina’s sake. Please come with me.’

‘No; it’s either him or me.’

She couldn’t believe he meant it. Surely Phil understood how important it was they went to Berlin?

‘That’s not fair. Think of Valentina. Don’t you think she deserves to meet Karel?’

‘She doesn’t care or know who the hell he is,’ Phil said hotly. ‘I’m her father, as far as she is concerned. But if you don’t value me in your lives any more, that’s fine. I’ll bugger off and leave you to it.’

He had stormed out of the room, slamming the door behind him. She had been stunned by his reaction. Where had it come from? She had expected Phil to come back to her that night so they could talk some more, but his side of the bed remained cold and she slept alone. In the morning, he had left a note, saying he had gone to London for a while. She had been so hurt and a part of her was angry with him. How could he be so selfish? She had promised Karel she would bring his child to meet him. That was not the sort of promise you break.

And yet it seems that Karel has broken it. That is unless he literally isn’t able to come. Maybe he is sick or not living in East Berlin any more. The only way she will find out is if she goes to his apartment.

It feels strange to be walking the streets of East Berlin again. Everyone seems to be on the move, heading west, either for the day or for ever. She finds the building in Prenzlauer Berg, where Karel lived, easily. After the last time, she would never forget the way. Despite its one-time grandeur, the façade looks even more dilapidated than she remembers: dirty, cracked windows, peeling paintwork and plaster crumbling off the walls to expose the brickwork. She walks through the front doors and up the stairs. Valentina is tired, dragging her heels and whining.

‘Come on, there’s a good girl. Not much further now,’ she encourages her.

Tina remembers the last time she was here in this building. Karel carried her up the staircase, the two of them covered in snow, the wet chill settled on her lap, yet she had been warmed by the heat from his chest, his heart beating against the heart of his baby girl inside her, his breath upon her forehead as he blew snowflakes off the top of her head. His presence in this building feels so real now that Tina imagines she can hear the strains of his cello floating down the staircase. Yet, when they get to Karel’s apartment, his name is no longer on the door. The music has gone and, instead, the doorbell echoes eerily out into the empty landing. She grips Valentina’s frozen hand tighter and says a silent prayer, yet she knows she is hoping against all hope. The door is flung open by a robust woman, probably about the same age as her, although her hair is completely grey. Tina speaks in English, since she has no German: ‘Does Karel Slavik live here?’ But the woman shakes her head, giving her an unfriendly look. Before Tina can ask if she knows where he is, she slams the door in her face.

Mother and daughter trail back down the stairs and into the street. It is beginning to get dark, an unpleasant drizzle of rain blowing horizontally into their faces and penetrating their coats. She can’t believe it’s over, that she will never see Karel again. And now she has lost Phil too. She is on her own. She shivers suddenly, her body jerking violently.

‘What’s wrong, Mama?’ Valentina asks, looking up at her with her big baby-girl eyes.

‘I feel a little sad and lonely,’ she tells her.

‘Don’t be sad,’ her daughter says. ‘You’re not lonely; you have me.’

Yes, but it’s not enough, she feels like saying. I need a man in my life to make me love myself, to make me feel whole.

Back in the hotel, she is so exhausted that she falls asleep still in her clothes, while reading a bedtime story to Valentina. In her dream, she finds Karel. He is living with those poor punks in one of the abandoned buildings on Schönhauser Allee. He is sitting on top of a pile of rubble, quite calmly, as if it is the most comfortable place in the world to be sitting. His cello is propped between his legs, and he is waiting for her and Valentina. She waves to him. ‘We’re here!’ she calls. ‘I brought her to you.’

Karel smiles back, looking down on Valentina with pride. He has such a magnanimous smile, full of understanding, compassion and love. He is a good father. He picks up his bow and he starts to play. Oh, it is the song he composed for Tina! She knows immediately. She stands beneath his rubble castle and listens to the sound of his love. It lifts her and Valentina up, so that, for a moment, their feet are no longer touching the ground. And as she watches him play his cello, she feels his bow across her naked body – the strings sawing across her breasts and catching on her nipples as he plucks her down below. He is playing her, his dexterous, nimble fingers sensing the inner vibrations of her body and bringing forth the music of her soul.

And, as he plays, she sees the shadows in the derelict buildings turn into people she once knew in East Berlin: Sabine and Rudolf, Hermann and Simone, and Lottie. Karel is the warmth and he is the light around which they all gather.

She wakes in a sweat again, her clothes soaking through to her skin. Valentina is fast asleep. She gets off the bed, and strips off. What could that dream mean? And then it occurs to her, there is one last possible route to finding Karel. She turns on the table lamp by her bed and hunts in her bag for her address book. She pulls it out and flicks through it until she finds Lottie’s old address in Berlin.

When Lottie opens her front door the next morning, Tina recognises her instantly. Her punk looks are slightly toned down – the black hair not quite so spiky, and her eyes not as heavily made up – but even so she still has that edginess that attracted Tina to book her as one of her models in the first place. Lottie gawps at her for a moment, speechless with shock at seeing her. It has, after all, been over five years.

‘My God, Tina!’ she exclaims. ‘And is this your daughter? Hello,’ she says to Valentina, bending down and offering her hand.

‘Hello; pleased to meet you,’ Valentina says, politely, in Italian.

‘Oh, so cute,’ Lottie says, straightening up. ‘So what are you doing here in Berlin?’ she gushes. ‘Well, of course, the Wall coming down . . . isn’t it so exciting? Since the ninth, every day has been one big party.’

She leads them into a messy kitchen. ‘Sorry, the place is in a state. Do you want a cup of tea?’

‘No, I’m fine, thanks. Have you been over the Wall yet?’

‘Of course; I went over at Brandenburg Gate on the ninth at exactly nine thirty p.m. It was incredible. I cried.’

‘Did you meet up with Sabine? You must have had such a family celebration!’

Lottie looks awkward, her pale cheeks blush. ‘Yes, my parents went over to see their family,’ she says, changing the subject. ‘The atmosphere in the city is so great . . . Finally, all Germans together . . .’ She beams.

‘And Hermann? Did you meet up with him?’ Tina asks her.

Lottie clutches her hands, her smile wiped off her face. ‘Hermann is dead,’ she says, looking away from Tina and out the smudgy window of her kitchen.

Tina bites her tongue. How could she have been so tactless?

‘I’m so sorry, Lottie. What happened?’ she asks her, softly.

‘That’s why I lost contact with my cousin, Sabine,’ Lottie says, offering Tina a chair at the table and sitting down opposite her. ‘I always suspected that her creepy boyfriend was Stasi, but it turns out that Sabine was an informer too.’

‘But she was such a lovely girl,’ Tina says, remembering the sweet Sabine.

‘She was weak, not lovely,’ Lottie says sourly. ‘That’s how she knew Rudolf, in fact. He was interrogating her and I guess he got some kind of mental control over her . . . terrified her into being an informer.’

‘But what has that got to do with Hermann?’ Tina probes.

‘I made the mistake of telling Sabine about Hermann and Simone, and the fact I brought them music to listen to and stuff to wear. She told Rudolf and next thing you know they were rounded up. For some reason they picked on Hermann. They let Simone go. The Stasi locked him up and started mentally torturing him. When they finally let him out he was really damaged –’ she taps her head – ‘he ended up killing himself. Slashed his wrists with a piece of broken glass.’

She turns away from Tina, suddenly noticing Valentina standing by her and staring at her with big, horrified eyes.

‘Sorry, I forgot about the kid . . .’ she mumbles.

‘It’s OK; she doesn’t understand English,’ Tina says, gently. ‘I’m really sorry about Hermann. And what happened to Simone?’

Lottie sighs, shakes her head. ‘You saw how sick she was . . . After Hermann was gone, she just gave up . . .’ Lottie’s voice breaks. ‘They are both dead, Tina. That’s why I stopped going to the East. I couldn’t bear it . . . I felt that somehow I was responsible for their deaths.’

Tina reaches out and puts her hand on Lottie’s arm. ‘You know that’s not true.’

Lottie shrugs, picks a packet of cigarettes off the kitchen table and offers Tina one.

‘No, thanks,’ Tina says, shaking her head.

Lottie lights up, puffing on the cigarette meditatively.

‘Does she want to sit down?’ she asks Tina, indicating Valentina, who is still standing motionless and staring at Lottie as if she is regarding an exotic creature rather than a person.

Tina turns to Valentina and, speaking in Italian, she tells her to stop staring and to sit down at the table. Valentina reluctantly slips on to a chair, but still she cannot pull her eyes away from the vision of Lottie.

Tina quells the butterflies in her stomach, takes a breath. She has to ask Lottie about Karel and yet she is scared of what she might tell her. She changes her mind and grabs Lottie’s cigarette packet, helping herself.

Lottie looks at her curiously, sensing that Tina is building up to something.

Tina takes a long, slow drag on her cigarette. ‘So, do you know what happened to Karel Slavik, the cellist?’ she finally spits out as casually as she can.

‘You don’t know?’ Lottie asks her.

‘No.’ She shakes her head, feeling a cold dread creeping into her stomach.

‘I knew about you and him,’ Lottie says, crushing the butt of her cigarette into an empty saucer on the table. ‘I watched that night in the car . . .’

‘Not in front of Valentina,’ she whispers, despite the fact that Valentina doesn’t understand a word they are saying.

‘Oh, sorry.’ Lottie scrutinises Valentina, meeting the child’s eyes for a moment. ‘Jesus!’ She whistles under her breath, looking back at Tina. ‘Now I know why you’d want to find Karel. She is the image of him.’

‘So do you know where he is?’ Tina asks, suddenly impatient.

She can’t bear it any more, the not knowing.

Lottie is looking at Valentina, transfixed. She shakes herself, as if breaking from a trance, before looking over at Tina and speaking so slowly it seems as if the words are being dragged from her.

‘Yes, I know where he is. I’ll take you.’

2013

She is right on the edge of the cliff, leaning over, more so than is safe. Yet Valentina doesn’t move. She is hypnotised by the clear blue sea, drawn into its glittering depths. Theo is down there somewhere.

The ocean mocks her, its hue the exact shade of her dead lover’s eyes. She feels such an intense loathing for this island, so wild and elemental, a place that she always loved before, and yet this very shoreline swallowed up Theo, took him away from her and left her broken.

The wind pushes into her back as she leans even further forward. It would be so easy just to slip off this cliff edge and drop into the sea below – so easy to join Theo in his watery grave. Seagulls circle above her head, crying out as if to warn her and yet she doesn’t step back to safety. Today is a year to the day that Theo disappeared into the Mediterranean Sea, off the island of Capri.

They never found a body. She heard that his parents had a memorial service for him in his home city of New York, but she refused to go. How could she meet Theo’s parents for the first time in such circumstances? To think that she had been worried about meeting them when he was alive, fearful of the commitment! She is ashamed to face them now.

Valentina cannot believe that she is still standing; that her heart is still pumping despite the fact Theo is dead. She twists the engagement ring on her finger, rubs the cut edges of the sapphire stone against her fingertip, an action that gives her comfort. She should take it off, bury it in the bottom of a jewellery box, but she just can’t let go of the last thing Theo gave her. She stares at that blue sea, and sees Theo’s eyes within it. ‘Speak to me,’ she begs, but the only sounds are those screaming gulls and the sea crashing on to the rocks below.

She sighs, and turns her head to look up into the sky. She sways on the edge as she watches the seagulls flying in and out of the blue void above her. She remembers another blue-sky day: she and Theo lying on their backs in the grass in Parco Sempione in Milan. It was a hot June day, not long after they had first started dating, nearly two years ago now. The two of them were staring up into the perfection of the blue abyss above them, holding hands.

Valentina remembers she had suddenly been filled with a spontaneous need to be intimate. She had rolled on to her side and climbed on top of him, closed her eyes and kissed him on the lips. She remembers they had been eating ice creams, and he was still sweet to taste. His lips were cool and creamy against hers.

‘Open your eyes,’ Theo had whispered.

She had not wanted to. She shook her head, burrowing her face into his tender neck and inhaling him.

‘Please, Valentina,’ Theo insisted. ‘Let me look at you.’

She had felt a little bullied. She didn’t want to break the trance of their bodies melting into each other under the hot sun. If she opened her eyes it would be like a separation.

‘What is it?’ she had snapped, whipping her head up and flashing her eyes at him, unable to hide the annoyance in her voice.

Theo looked back at her, unblinking, white heat glinting within cool blue, and her irritation seeped away. He said nothing, just held her with this gaze that spoke a thousand words. Deep down she knew then how he felt about her. It frightened her to the core. No man had ever looked at her in this way; no man had seen inside her. She knew right then that he loved her, months before he ever said it to her, and nearly a year before she could admit it to him. And yet, as his face broke into a smile, her heart had lurched and she too had fallen.

Those were the moments, she now realises, on a random June afternoon in a park in Milan, when we first fell in love.

‘Don’t look so serious, Valentina,’ Theo had teased her, wrapping his arms around her and pressing her tightly against his chest so that she could feel his heart beat against hers. She had let herself sink into him. She had bathed in the golden warmth of his comfort. For the first time in her life, she had not felt alone.

Valentina drops her head, looks back down at the tempestuous sea crashing off the Capri coast, its demons calling to her. She inches even closer to the edge of the cliff. She is so close to giving up, and yet the memory of that June day reawakens and she hears Theo’s voice again: ‘You are special, Valentina,’ he had said.

‘Everyone is special,’ she had retorted.

‘Of course,’ he said patiently, ‘but what I am trying to say is that you are special to me. I have never met a girl like you before.’

She had rolled off him on to the grass, sat up and looked down at him.

‘You do know that is a very corny line . . .’

He shaded his eyes with his hands and looked up at her. Shadows fell across his face. ‘I mean it,’ he said, sounding serious. ‘You are everything: beautiful, clever and talented . . . You are sexy, so sexy.’ He smiled. ‘But what makes you even more attractive to me is who you are, and what you do.’

She had looked back at him in surprise, unable to think of what to say in reply. No other man she had been with had ever been interested in her work; in fact, they had usually been threatened by her drive and focus, and especially by her successes.

‘Promise me something, Valentina,’ Theo had said, raising himself so that he was leaning back on his elbows. ‘No matter what calamities in life you have to face, you will always take photographs.’

‘But I am just doing the same thing that my mother did: fashion shoots . . . I am just copying her.’

He shook his head, with a face that said he knew better. ‘There’s more to you than being Tina Rosselli’s daughter. There is a depth to your pictures that she doesn’t have. I have every faith that your work will go through many incarnations . . .’

She gave his arm a friendly pinch, a little embarrassed by his belief in her. ‘You are beginning to sound like an art historian,’ she protested.

‘Well, now, that would make sense, wouldn’t it, seeing as that is precisely what I am?’

When they first met, Valentina had been surprised to discover that Theo was a Professor of Art History at the University of Milan. He had struck her as the least fusty academic she had ever met – always so lively and witty, and wanting to discover new art in Milan. He was forever taking different perspectives, looking at art in a different way, and he encouraged Valentina to break out of the boundaries of her profession as a fashion photographer. He had taught her so much and not just about art, but about films, books, music, politics, history. Valentina remembers now that even in those early days she had been a little confused by this dynamic man, always on the move, disappearing off on lecture tours and consulting with art dealers all around the world. He had not seemed what he claimed to be. And she had been right. Sure, Theo was an academic, but he was something else too, something dangerous and clandestine, a profession that had ultimately led to his death.

It should have been her, she thinks, who drowned this day a year ago. She nearly had. But Theo had saved her. It seems that he had given his life for hers, yet she wants to tell him so badly that her life is worth nothing to her without him by her side.

She wants to jump off the cliff. She feels herself pulled towards the edge again. She wonders if her body will be battered by the rocks below. Would they kill her first, or could she fall clear of them and drop into the sea? Could she sink to the bottom like a stone, gulping in sea water until her lungs burst? The urge to let go is so strong inside her and yet Valentina finds herself stepping back.

Promise me something, Valentina. No matter what calamities in life you have to face, you will always take photographs.

She had promised him, that’s the problem. She sighs, opens her bag, digging around in it until she finds her digital camera. She turns it on, looks at the small screen, directs it down at the raging blue sea and takes a photograph. She turns around, with her back to the sea, stretches out her arm and turns the camera on herself, not sure what she might come up with as she spontaneously clicks. When she looks back at the photographs she has taken, she sees parts of her face – her windblown hair, her sorrowful eyes – against the startling blue backdrop of the Mediterranean, and the chalky cliffs behind her. She feels a little better already. By taking a picture of herself, she is able to step out of her emotions and document a process. Is it the process of her grief? For surely this is why she is in Capri in the first place? Her friends had thought she was maudlin coming here; in particular, Leonardo, who had written her a long email advising her not to go back.

Leonardo had been with her that desperate week a year ago. She had phoned him to tell him that Theo had gone missing and the next day Leonardo had just turned up. She had been so relieved to see him. He had not left her side, accompanying her all the many times she took rowing boats out to the blue grotto to scan the cave for signs of Theo. The water had looked floodlit from below, the refracted daylight beaming up through its blue sheets. When she dipped her hands into its azure glitter, they became silver. This magical, iridescent place was now transformed into the gates of hell for Valentina. She could see right to the bottom of the sea in the blue grotto and there was nothing there. What more could she find that the police hadn’t? Yet Leonardo traipsed the island of Capri with her as she spoke to the fishermen and the shopkeepers, the other tourists and the owners of the trattorias. She could not believe that Theo had drowned. And yet it was the only logical conclusion, for she knew he would never have run away from her. It was inconceivable. They had just got engaged.

She remembers the last night of her search. Over dinner, Leonardo had told her, as gently as he could, that it was time she went back to Milan. The police would contact her if anything turned up. She had been furious with him, and yet in her heart she knew he was right. She had drunk too much wine and it had fuelled her anger.

Back in the hotel room, she had been cruel to her friend, and accused him of having ulterior motives for being there with her. She will never forget the hurt in Leonardo’s eyes; yet, at the same time, there was a flicker of his eyelashes, a blink that told her she had hit a nerve. She had seen a shard of his feelings for her.

‘You want me to give up on Theo,’ she had said.

‘Valentina, I am trying to help you,’ Leonardo had protested. ‘Theo was one of my best friends.’

‘Don’t talk about him in the past tense,’ she had screamed at Leonardo. ‘He could still be alive . . . he could be hurt . . . lost . . . Glen could have kidnapped him.’

‘From what the police said,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...