- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

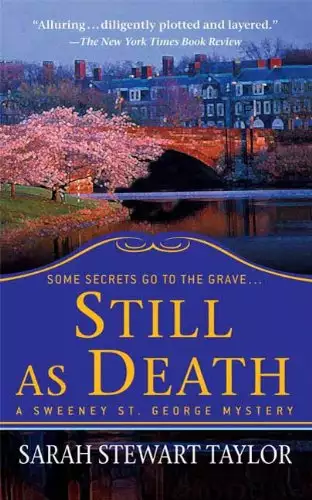

Synopsis

Art history professor Sweeney St. George is in the middle of putting together an exhibit on her specialty, "the art of death," for the university museum when she makes an unusual discovery: A valuable piece of Egyptian funerary jewelry that should be in the museum's collection seems to be missing. Searching for answers, Sweeney learns that a student intern at the museum was the last person to check out the piece, a young woman who died of an apparent suicide soon after she handled the piece, more than twenty-five years ago.

Going on with the exhibition without the intricately beaded Egyptian collar, Sweeney can't let it drop altogether. Nor can she forget the student, Karen Philips, who died just a few months after working with the piece. A little digging shows that Karen was working at the museum the night it was robbed, that same year, and Sweeney becomes even more curious. But her interest in mysteries past pales when a present-day murder brings Sweeney and her colleagues at the museum under the Cambridge Police Department spotlight in the person of Detective Tim Quinn, whom Sweeney has worked with before.

In the latest installment in this rich and fascinating series, Sweeney and Tim go after a killer, trying to resolve questions both immediate and decades-old before it's too late.

Release date: April 1, 2007

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Still as Death

Sarah Stewart Taylor

Sweeney St. George awakened slowly, aware only of a sense of breathlessness, as though something was interfering with the air getting into her mouth and down into her lungs. She opened her eyes to darkness, darkness, she realized, of a specific texture, soft, and smelling faintly of . . . fish.

She rolled over and sat up, displacing the large black cat that had been sleeping nestled up next to her face, her prolific red, curly hair a comfy cat bed. The cat, now sitting up in the dignified iconic pose of his species, blinked a few times and looked indignantly at her as if to say, "I had just gotten comfortable, thank you very much."

Sweeney gently pushed him off the bed, and the cat stretched as he landed gracefully on the floor, then turned and sprang onto the windowsill and out the slightly open bedroom window onto the fire escape. He turned back, gave her a farewell glance through the window, and was gone.

"What?" the other inhabitant of the bed asked sleepily. "What's wrong?"

Sweeney curled herself against the long back and whispered into warm skin, faintly scented by the dark brown ovals of soap sent every month from London. "Nothing, just the General. It's okay. Go back to sleep."

She lay there for a few minutes, listening to his deep, even breathing, then got out of bed, slipped into the silk robe on the rocking chair in front of the window, and went into the kitchen. It was nearly six and the sun was rising above the Somerville skyline, giving everything a clean and optimistic aspect that Sweeney appreciated. She got the coffeemaker going and broke two eggs into a frying pan, flipping them onto a plate when they were just barely set. Two pieces of buttered toast and an orange completed her breakfast, and she sat happily munching as she watched her next-door neighbors enjoy their own breakfast on their second-story balcony. It was late August and al fresco dining offered a respite from the current heat wave. Through the open kitchen window, Sweeney felt a slight breeze and turned toward it for a moment. As she finished eating and got up to rinse her dishes in the sink, she heard a whoosh and turned to find the General sitting on the kitchen windowsill, watching her.

"What are you doing back here?" she asked him. "I thought you'd gone for the day." The cat, who had been living with Sweeney for ten months now, tended to leave through one of the windows in her apartment early in the morning and return at night for dinner and bed. What he did during the day she had no idea.

Sweeney had inherited the General, and every time she looked at him she thought of the young boy she had befriended the previous fall. Dying of leukemia, he had made her promise to care for the cat. When she had first brought him home the previous fall, she had tried to get him to use a litter box and be a proper indoor cat, but he had hated using the box as much as she had hated cleaning it, and when she accidentally left the bedroom window open one day, they both discovered a routine that suited them. Sweeney did not want to fuss over him too much. He, in turn, did not like being fussed over.

He looked meaningfully at her plate, still smeared with egg yolk, and she set it on the counter for him. In a few seconds, the plate was clean and shiny, and the General used one huge paw to wash his whiskers before disappearing again out the window. "Have a nice day," Sweeney called after him.

Once she'd washed up, put on jeans and a linen blouse and tied her hair up and out of her face against the heat, she leaned over the bed and brushed its occupant's dark fall of hair away from his forehead. "Ian?" she whispered. "I'm heading out to the museum. It's seven. I'll see you tonight, okay?"

He opened his eyes and looked up at her, squinting into the sunlight. His glasses were on the bedside table and she knew he saw only the vaguest outline of her face. "But it's early," he said. Ian didn't usually get to his office until nine or ten.

"I know, but the exhibition opens in three weeks and I still have so much to do. The catalogs are done and I have all this text to write. They're still painting the galleries and I need to make sure all the framing is right. I told Fred and Willem I'd get in early."

"Okay, okay, I can take a hint. However . . ." He reached up and pulled her back into bed. "I assert that I ought to be allowed to have a small memento of your existence, since I shall have to do without you all day."

"But I have so much to do . . ." She ran her hands over his bare chest, trying to decide if she wanted to be seduced. His skin was as warm as sun-baked stone, his arms around her sure and familiar. It had been almost six months since he'd arrived in the states to open a Boston office of his London auction house, and Sweeney often found herself surprised at how quickly they'd settled into domesticity. They had known each other for nearly two years now, she supposed, so even though they'd been in the same city only since January, it made sense that there had been no need for prelude. But still . . . Sometimes when she came home at night and found him reading the papers on her couch or wrapped in his navy blue, monogrammed bathrobe and cooking dinner, she had the sense of having entered someone else's house. She sometimes thought to herself, Who is this man? for a moment before she remembered, Oh, it's Ian.

In any case, she thought, looking at him, he was a very handsome man and a very kind one and, at the moment, a very sexy one.

"Just one thing you have to do here, though," he murmured, unbuttoning her blouse. She thought about protesting, then relaxed into his arms.

"Okay," she whispered into his ear. "But only because you're so persuasive."

Forty minutes later she was walking through the front door of the Hapner Museum of Art, holding a cardboard cup of coffee. The Hapner was arguably among the most distinguished college or university art museums in the country, and like most art museums connected with institutions of higher learning, the Hapner had a strange and eclectic collection, largely dependent on original holdings and gifts by alumni or benefactors. In addition to works of American, European, and Near Eastern art, the Hapner housed the university's well-rounded collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities—thanks to the interest of its director and Egyptologist Willem Keane and the proliferation of wealthy and well-connected alumni associated with the university through the years.

The grand gray stone façade of the museum presented a paternal and imposing aspect to passersby which, Sweeney had always thought, seemed singularly uninviting. She stopped for a moment to look up at the banner over the main entrance. still as death: the art of the end of life it read, announcing Sweeney's exhibition of funerary art from the museum's collection. It panicked her to see the words up there when she hadn't even finished putting everything in place.

"Hi, Denny," she called out as she climbed the ten stone steps to the main foyer. In contrast to the outside of the museum, the foyer was surprisingly welcoming, bathed in sunlight from the soaring skylights high above the marble floor. The antiquities were housed in the basement and on the main floor, with the European and American galleries on the second, third, and fourth levels. The museum was constructed around a central courtyard, open all the way to the ceiling, with wraparound balconies on each floor that led into the galleries. Standing in the courtyard, you could look all the way up to the balconies of the fourth floor high above you.

The security guard raised a hand and answered, "Hey, Mizz St. George." She had tried to get him to call her by her first name long ago, but Denny Keefe, who had been working at the museum for thirty years and apparently using the formal address for all that time, wouldn't budge. "Hot day, huh?"

"Yeah. Again." She smiled at him, glad as she always was that the museum administration hadn't let Denny go for someone younger and spryer, but rather supplemented his presence with a revolving collection of imposing-looking twenty-year-old bodybuilders to safeguard the collection. Denny himself wasn't a very convincing security guard, but he was a cheerful presence and Sweeney liked him. He had always reminded her a little of a frog, with his large, egg-shaped eyes and his longish white hair, which he kept smoothed to his head with applications of a slippery substance that smelled vaguely of sandalwood. His uniform had never fit him properly and the loose green fabric added to the effect. Sweeney wasn't sure what he would do if he were actually faced with a determined art thief, but she liked the idea that he might just put out his tongue and . . .

She headed up to the third floor, where a series of connected galleries would soon house her exhibition. It had long been a dream of Sweeney's to plan an exhibit of the things she studied: tombstones and mourning jewelry, death masks and Victorian postmortem photographs, and Egyptian burial items.

The pieces had all been chosen, and she had spent the previous year working with museum staff to create installations and displays for the items. As she walked into the first of the linked galleries, she saw that one of the Egyptian sarcophagi had already been carried up. Tomorrow they would be bringing up other Egyptian burial equipment from the basement galleries. Though they could no longer display the museum's mummy, they could display many of the items that would have been buried with it. The elaborate preparations of the bodies of the ancient Egyptians—first the nobility but eventually those on other levels of society as well—were great evidence for the overriding assertion of Sweeney's exhibition: that death and speculation about the afterlife were the motivating factor for much of the great art of the world. By choosing representative pieces of funerary art from different eras, she hoped to show the diversity of responses to human mortality.

Today she had to choose a piece of Egyptian funeral jewelry to replace one that the conservation department had determined wasn't in good enough shape to be displayed. The catalog was already completed, of course, but she and Willem had decided that they should just choose another piece. She hadn't found exactly what she wanted among the displayed items, so she went down to the storage areas located beneath the museum to browse the files.

The art and antiquities displayed in the Hapner's galleries represented only a tiny percentage of the museum's holdings. The rest of the items were stored in five large rooms beneath the museum. Banks of file cabinets flanked the large workspace where Harriet Tyler, the collections manager, had her office and controlled access to the rooms of priceless and not-so-priceless treasures.

Every piece in the museum's collection, no matter when it had been acquired or donated, no matter how insignificant it might be, had a file containing information about its history and connection to other pieces owned by the museum, and Sweeney went to the Es and found the files kept on examples of ancient Egyptian jewelry.

Her choices were very nearly endless. The museum had a huge number of Egyptian antiquities, most of them unimportant pieces that had been gifted to the university long ago. They were used for research, brought out for special exhibitions, or loaned to other museums, but for the most part, they remained in storage. Attacking the row of files, Sweeney felt a bit like a prospective dog owner at the pound. Who would the lucky antiquity be?

She had already included the more obvious examples of Egyptian funerary art, the sarcophagi and the canopic chests and jars that had held the internal organs of entombed ancient Egyptians. What she didn't have was an example of the elaborate jewelry that had been buried with the mummies, the amulets and collars and pectorals that archaeologists often found among the layers of linen wrapping the prepared bodies. Some jewelry from ancient Egypt would be a nice counterpoint to the Victorian mourning jewelry she was also including in the exhibition.

There were scores of insignificant pieces, scarab rings and gold hoop earrings that had been donated years ago and weren't seen by anyone but students anymore. Sweeney remembered coming down to the museum as a graduate student and looking at some New Kingdom amulets for a paper she was writing about funerary mythology.

Now she found listings for a number of amulets in the shape of various animals and flowers that had special meanings for the ancient Egyptians: hippos and flies and vultures and lotuses and fish. She put them aside, thinking it might be interesting to include a few, but quickly forgot about them when she opened the file folder labeled, "Beaded Collar. 18th Dynasty." On the outside was a little grid with a name and date scrawled in it. Sweeney assumed it was a record-keeping device to track everyone who had taken the piece out of storage. It appeared that the last person had been someone named Karen Philips.

There was a photograph of an absolutely magnificent piece of jewelry stapled to the inside of the folder, and Sweeney spread it out on one of the worktables to get a better look. The photo showed an intricately beaded collar made of gold and faience that would have covered the chest area of some very lucky mummy. It had falcon heads where the strings of beads gathered together on either side, and the eyes and beaks were accented with blue and amber-colored stone. The file was thick with paperwork, shipping labels and lists and receipts, and as Sweeney looked through the documents she decided they had to represent the object's provenance or history of ownership. Most pieces donated to the museum were accompanied by similar paperwork showing that the person who was donating it was the actual owner. From the paperwork she saw that Arthur Maloof had donated the collar in 1979. Well, well, well. The basement gallery had recently been renamed the Maloof Gallery, and she knew that Arthur Maloof had donated the gold funerary mask that was the crown jewel of Willem's collection.

She looked at the photograph again. Why wasn't the collar on display? It was as beautiful as anything Sweeney had seen from the period, almost as stunning as some of the collars found in the tomb of Tutankhamen, though the beadwork was finer and more delicate, stylistically different. She decided she'd ask Willem if he could have the collar brought out of storage.

The collar decided upon, Sweeney headed back up to the third-floor galleries. The next order of business was figuring out the placement of the twenty postmortem photographs in the exhibition. She'd always loved the haunting photographs of deceased loved ones that had been so important to the Victorians. Because of her desire to include them in the exhibit, she'd gotten important support from Fred Kauffman, the Hapner's curator of photography. All of the pieces depicted the deceased, most of them dressed in their finest clothes and posed in coffins or upright in chairs. Sweeney had always been fascinated by the oddly moving postmortem photographs that had been so popular during the nineteenth century. For many Victorians, the postmortem portrait was the only one they would ever sit for. Families would spend what were then exorbitant sums in order to have a final image of a loved one.

She was starting to go through the framed photographs and daguerrotypes and tintypes stacked against one wall when Fred came into the gallery.

"Morning, Sweeney. How's it going?"

"Very well, thanks." He looked over her shoulder at a set of daguerrotypes of a young girl. She was dressed in what looked like a white christening dress and propped up in a fancy wing chair. To the unpracticed eye, she might have been a pale but lively six-year-old posing for the camera. But the static, staring eyes told a different story, and Sweeney shivered a little, the way she always did when looking at postmortem photos of children. There were a lot of them around. Epidemics felled so many infants and children. She always thought of those parents, left with a single image of the child who would never grow or change.

The process of choosing the photographs that would be included in the exhibit had been a push and pull between Sweeney's interests and Fred's. She had tried to be conscious of his opinions and expertise, but she kept remembering a report card she'd received in the third grade: "Sweeney does not work well as part of a team," the teacher had written. "She prefers to do group projects on her own and does not like to share credit or responsibility."

But she liked him enough to want to make it work, and she was proud of how the exhibition had turned out. Fred was a short, well-padded guy with curly gray hair who was passionate about photography. He wore unfashionably large glasses that reminded Sweeney of a camera's telephoto lens, and though she knew he had gotten his Ph.D. from the university in the late '70s and was a good twenty years her senior, he had always treated Sweeney as an equal. They had gotten to know each other fairly well over the last few months, and she and Ian had been out to dinner with Fred and his wife, Lacey.

Fred was giving his opinion about where to hang a particularly haunting daguerrotype of a young girl when Willem stuck his head in to see how they were doing. Every time she saw him, Sweeney couldn't help thinking about the first time she'd met Willem. She'd been an undergrad, doing an internship at the Hapner the spring semester of her junior year, and she'd been assigned to work with Willem. He'd been curator of ancient art then, and he'd had Sweeney doing research on an Egyptian sarcophagus that had been given to the university. She had been nervous, very much in awe of the good-looking man who was known around campus for being very brilliant and very icy, and when he'd said, "Well, have you gotten inside yet?" she hadn't realized he was making fun of her. She'd almost climbed into one of the stone vessels before he'd cracked a smile and let her off the hook.

She and Willem got along well now, and she knew he respected her work, but she always felt a little bit like a nineteen-year-old student around him. He was a tall, rangy man of sixty, with perfectly cut gray hair and a professorial mustache. Unless he had a meeting or event, he always wore a gray or tan cashmere sweater, jeans, and expensive running shoes.

"Sweeney, the catalog looks terrific," he said. "I'm really pleased." He was holding one of the paperbound catalogs, with the title of the exhibition superimposed over one of the postmortem photos. There had been a lot of talk about whether it was too macabre an image to put on the cover, but Sweeney had eventually gotten her way. It worked well, she saw now, the cover image literally confronting the viewer with the reality of death, and with the desire of the living to memorialize those who had passed, a desire that had led to a highly stylized mourning ritual. These were themes that Sweeney examined throughout the exhibition, from the funerary items from ancient Egypt to the modern-day mourning items she'd found—memorial tattoos and car decals as well as contemporary mourning jewelry.

Willem held up the catalog. "Good work. I wish I could say the same for her." He nodded toward the hallway, and Sweeney knew he was referring to Jeanne Ortiz, a professor of photography and women's studies who was curating an exhibit on depictions of women in American photography that would run sometime over the winter. Sweeney liked Jeanne and was interested to see the exhibit, but she knew that Willem couldn't stand her and found the somewhat radical premise of her show specious to boot. When he'd discovered that Jeanne was planning on including a series of photographs from Hustler and Penthouse, he'd raged for days.

Sweeney and Fred exchanged a look, neither one wanting to get Willem going on Jeanne's various transgressions.

"Well, I'm off," Willem said. "Tad has a pile of papers for me." Tad Moran, Willem's assistant, was always trying to get Willem to sit down and sign papers while Willem preferred to spend his time roaming his museum.

"Before you go," Sweeney said, jumping up and going over to her worktable to find the file containing the information about the collar, "I think I found another piece I want for the exhibition." She held out the folder.

"Great," Willem said, distracted. "I don't have time, but show it to Tad. He'll arrange everything and I'll have a look and see what I think. Good progress. I'm very, very pleased."

Fred stood up as Willem turned to go. "Do you have a minute, Willem? I just wanted to talk to you about the Potter Jennings exhibit. The book's out in December and I was thinking . . ." Fred's biography of the American photographer Potter Jennings was, in many senses, his life's work, and Sweeney knew he was hoping that Willem would agree to an exhibition that would help promote it. Willem, a singularly focused Egyptologist and antiquarian, didn't seem very excited about it. Sweeney knew that the only reason she'd been able to get Willem to be supportive of her exhibition was that she was including some of his favorite pieces of Egyptian burial items from the museum's collection.

"Okay, walk with me," Willem said, looking bored. "See you, Sweeney."

"I'll leave you to it, then," Fred said to Sweeney. Something came over his face suddenly. He's ashamed, Sweeney thought. She watched them walk out of the gallery and along the hallway, then went back to her work.

By four o'clock, she'd figured out the placement of all of the photographs and was feeling considerably more confident that the exhibition would be ready by the date of the opening. She headed over to the museum's administrative offices to ask Tad about the collar.

The museum staff's offices were on the second floor of the annex, a modern glass addition that had been built onto the museum in the '70s and provided office space for Hapner staff as well as members of the History of Art Department like Sweeney. She used her electronic passkey to cross over to the annex, knowing that the system was recording the time she passed through the doorway as well as her identity. The security was necessary, of course, but it always felt a little Big Brother to Sweeney.

Tad Moran was talking to Harriet out in the reception area, and when he saw Sweeney he gave her a shy smile and said, "Hi, there. How are things coming along?" before glancing nervously behind him. Tad always seemed scared of something, Sweeney thought. Willem probably. Tad had been working for him for years, and she'd always wondered why he hadn't moved on to another job. Willem was brilliant but famously a tyrant to work for. Tad had been quite a gifted Egyptologist, apparently, and had chosen to be Willem's right-hand man rather than make a career of his own. She'd once asked Fred about it, and he'd said that he thought he'd heard that Tad had a sick wife at home, something like that. He wasn't a bad-looking guy, Sweeney thought, though he appeared not to have changed his haircut or clothes since he'd been in prep school. His dark brown hair was parted unfashionably on the side, and he always wore khakis and neatly pressed blue oxford cloth shirts with red and blue or yellow and blue striped ties. Though he must be in his early forties now, he looked far younger, his thin face nearly unlined and his short brown hair untouched by gray.

"Fine. Willem said to ask you about this piece. It's in storage, I guess. But I'd love to make a last-minute addition." She held out the file folder and added, "We know it's not in the catalog or anything. It's just to provide some more context," when she saw that Tad looked a little panicked. It was very late to be making additions.

He jotted down the numbers written on the outside and said he'd arrange for it to be brought up. "What are you going to do about displaying it?"

"I think there's room in the cabinet that's already there."

"Good. I don't know if you've got time to build something new."

"You definitely don't have time to build something new," Harriet offered. Sweeney resisted the urge to slap her. Harriet was a perfect collections manager, a hyperresponsible cataloger and record keeper. Her precision got on Sweeney's nerves. Her bobbed gray hair hardly moved when she shook her head, and her clothes were always perfectly matched, brown shoes with brown slacks, black shoes with black slacks. Sweeney always had the feeling Harriet didn't like her.

"Fine. I'm not going to." Sweeney turned to go, then remembered the file. "Hey, all these old documents in here, what are they for?" Sweeney showed him the documents, the inventories and shipping labels and lists.

"Probably someone was researching the provenance," he said.

"That's what I thought. Does every item in the collection get the same treatment?"

"Not always," Tad said vaguely.

But Harriet jumped in, pleased at an opportunity for didacticism. "You may have heard about museums having to search their collections for Nazi art. Well, we're also particularly concerned with antiquities. There was a 1970 UNESCO convention that prohibited the removal of any more antiquities from their countries of origin, and then a 1983 law passed here in the states that basically said the same thing. It had been a particular problem in Egypt, where you could buy antiquities right on the street. The UNESCO treaty meant that if you wanted to accept or buy a piece, you had to be able to prove that it was part of a legitimate collection that had been assembled before 1970. That's probably a piece that was given to the museum and someone was just checking to make sure everything was in order."

Tad turned to go. "I'll let you know when they can bring it up for you."

"Thanks. Do you know why it's not on display? It's really beautiful. I just thought Willem might have some reason."

"I couldn't say," Tad told her. "We have a lot of beautiful things that we can't display for whatever reason."

He was right, Sweeney reflected as she walked out into the humid afternoon air. She was just going to have to be satisfied with that.

Copyright © 2006 by Sarah Stewart Taylor. All rights reserved.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...