Introduction to the

Perennial Edition

by Peter Straub

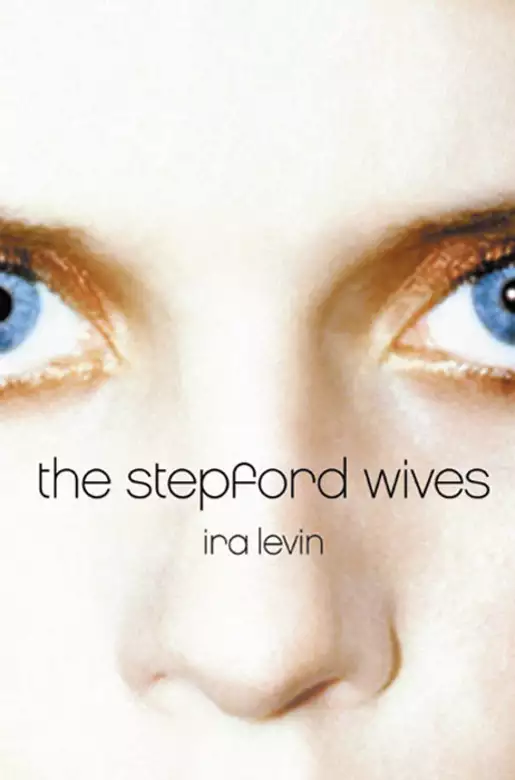

THE STEPFORD WIVES, along with almost everything else written by the admirable Ira Levin, does honor to a demanding literary aesthetic that has gone generally unremarked due to its custom of concealing itself, like the Purloined Letter, in plain view. Polished and formal at its core, this aesthetic can be seen in James Joyce’s Dubliners, the novels of Ivy Compton-Burnett, the work of California Gothic writers like Richard Matheson and William F. Nolan, and in Brian Moore’s last, drastically underappreciated six novels. Clearly adaptable over a wide range of style, manner, and content, it emphasizes concision, efficiency, observation, accuracy, effect, speed, and the illusion of simplicity. Fiction of this kind rigorously suppresses authorial commentary and reflection in its direct progress from moment to moment. This emphasis on a drastic concision brings with it a certain necessary, if often underplayed, artificiality that always implies an underlying wit, although the individual works themselves may have no other connection to humor. Such fiction possesses the built-in appeal of appearing to be extremely easy to read, since the reader need do no more than float along on the current, moving from a paragraph centered around a sharp visual detail to a passage of dialogue, thence on to another telling detail followed by another brief bit of dialogue, and so on.

all easy to write clear, declarative prose—transparency evolves from ruthless cutting and trimming and is hard work—while lumpy, tangle-footed writing flows from the pen as if inspired by the Muse.

ine abruptly tears up her tennis court to install a putting green for her husband, now understood to be “a wonderful guy.” At this point we do not share the author’s awareness that Bobbie has one month left before the dread transformation, Joanna two. Like our heroine, we become aware of the timetable only after Bobbie Markowe returns from a brief marital vacation with enhanced breasts, a slimmer bottom, and a newfound passion for ironing.

mber they gave a dinner party …”

And there we are again, located within a dinner-party scene bristling with apprehension that will come to a climax a mere 900 words later, with Charmaine blandly going on about cleaning her house, while workmen cut up the metal fence around her already demolished tennis court.

it isn’t mimetic fiction. Levin created the same kind of deliberately genre-parodic, over-the-top exoskeleton for The Boys from Brazil, where Nazi scientists breed little Führer clones and adopt them out to families akin to Hitler’s. Oblivious to his satire, lots of heavy-footed thriller writers immediately began to imitate precisely what he had been lampooning. Similarly, not a single reviewer of Son of Rosemary, Levin’s most recent novel, understood that it, too, satirized the excesses of its own supposed genre.

The funniest revelation of wholehearted male piggery occurs very early in the book, when the Eberharts have been in town no more than a few weeks. At two in the morning, after Walter Eberhart has returned from his first visit to the Men’s Association, the shaking of the bed and the squeaking of bed-springs awaken his wife. Joanna quickly realizes that her husband is … masturbating! “Well next time wake me,” she says, and before long they are enjoying the best sex they’ve had in years. Something has ignited Walter’s fuse, and not until much later do we realize—as Joanna never does—that it was the world-class fantasy object described to him by the grinning lads up on the hill.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved