- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

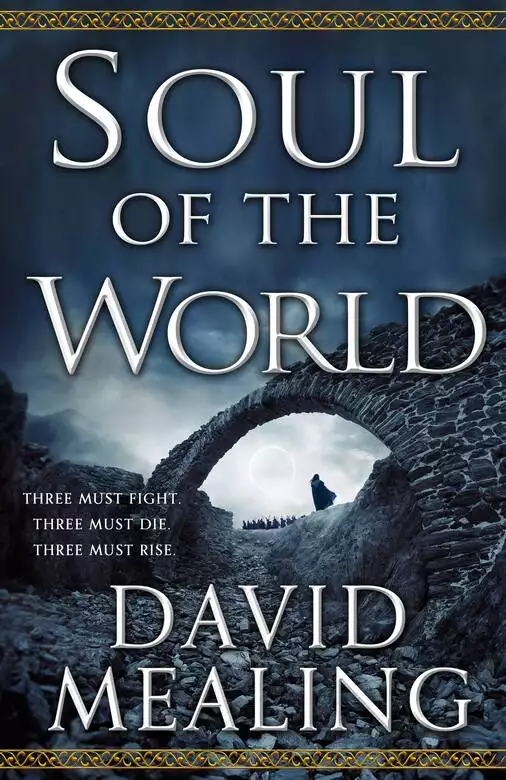

Synopsis

It is a time of revolution. The city of New Sarresant simmers with discontent against the crown. In the wilds, a new magic threatens the dominance of the tribes. On the battlefields, even the most brilliant commanders struggle in the shadow of total war.

A darkness is rising. Three heroes must stand against it - or the world will fall.

Soul of the World is a stellar debut from a major new talent, an epic fantasy perfect for fans of Brandon Sanderson, Robert Jordan and Brent Weeks.

Release date: June 27, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 656

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Soul of the World

David Mealing

The Royal Palace, Rasailles

Throw!” came the command from the green.

A bushel of fresh-cut blossoms sailed into the air, chased by darts and the tittering laughter of lookers-on throughout the gardens.

It took quick work with her charcoals to capture the flowing lines as they moved, all feathers and flares. Ostentatious dress was the fashion this spring; her drab grays and browns would have stood out as quite peculiar had the young nobles taken notice of her as she worked.

Just as well they didn’t. Her leyline connection to a source of Faith beneath the palace chapel saw to that.

Sarine smirked, imagining the commotion were she to sever her bindings, to appear plain as day sitting in the middle of the green. Rasailles was a short journey southwest of New Sarresant but may as well have been half a world apart. A public park, but no mistaking for whom among the public the green was intended. The guardsmen ringing the receiving ground made clear the requirement for a certain pedigree, or at least a certain display of wealth, and she fell far short of either.

She gave her leyline tethers a quick mental check, pleased to find them holding strong. No sense being careless. It was a risk coming here, but Zi seemed to relish these trips, and sketches of the nobles were among the easiest to sell. Zi had only just materialized in front of her, stretching like a cat. He made a show of it, arching his back, blue and purple iridescent scales glittering as he twisted in the sun.

She paused midway through reaching into her pack for a fresh sheet of paper, offering him a slow clap. Zi snorted and cozied up to her feet.

It’s cold. Zi’s voice sounded in her head. I’ll take all the sunlight I can get.

“Yes, but still, quite a show,” she said in a hushed voice, satisfied none of the nobles were close enough to hear.

What game is it today?

“The new one. With the flowers and darts. Difficult to follow, but I believe Lord Revellion is winning.”

Mmm.

A warm glow radiated through her mind. Zi was pleased. And so for that matter were the young ladies watching Lord Revellion saunter up to take his turn at the line. She returned to a cross-legged pose, beginning a quick sketch of the nobles’ repartee, aiming to capture Lord Revellion’s simple confidence as he charmed the ladies on the green. He was the picture of an eligible Sarresant noble: crisp-fitting blue cavalry uniform, free-flowing coal-black hair, and neatly chiseled features, enough to remind her that life was not fair. Not that a child raised on the streets of the Maw needed reminding on that point.

He called to a group of young men nearby, the ones holding the flowers. They gathered their baskets, preparing to heave, and Revellion turned, flourishing the darts he held in each hand, earning himself titters and giggles from the fops on the green. She worked to capture the moment, her charcoal pen tracing the lines of his coat as he stepped forward, ready to throw. Quick strokes for his hair, pushed back by the breeze. One simple line to suggest the concentrated poise in his face.

The crowd gasped and cheered as the flowers were tossed. Lord Revellion sprang like a cat, snapping his darts one by one in quick succession. Thunk. Thunk. Thunk. Thunk. More cheering. Even at this distance it was clear he had hit more than he missed, a rare enough feat for this game.

You like this one, the voice in her head sounded. Zi uncoiled, his scales flashing a burnished gold before returning to blue and purple. He cocked his head up toward her with an inquisitive look. You could help him win, you know.

“Hush. He does fine without my help.”

She darted glances back and forth between her sketch paper and the green, trying to include as much detail as she could. The patterns of the blankets spread for the ladies as they reclined on the grass, the carefree way they laughed. Their practiced movements as they sampled fruits and cheeses, and the bowed heads of servants holding the trays on bended knees. The black charcoal medium wouldn’t capture the vibrant colors of the flowers, but she could do their forms justice, soft petals scattering to the wind as they were tossed into the air.

It was more detail than was required to sell her sketches. But details made it real, for her as much as her customers. If she hadn’t seen and drawn them from life, she might never have believed such abundance possible: dances in the grass, food and wine at a snap of their fingers, a practiced poise in every movement. She gave a bitter laugh, imagining the absurdity of practicing sipping your wine just so, the better to project the perfect image of a highborn lady.

Zi nibbled her toe, startling her. They live the only lives they know, he thought to her. His scales had taken on a deep green hue.

She frowned. She was never quite sure whether he could actually read her thoughts.

“Maybe,” she said after a moment. “But it wouldn’t kill them to share some of those grapes and cheeses once in a while.”

She gave the sketch a last look. A decent likeness; it might fetch a half mark, perhaps, from the right buyer. She reached into her pack for a jar of sediment, applying the yellow flakes with care to avoid smudging her work. When it was done she set the paper on the grass, reclining on her hands to watch another round of darts. The next thrower fared poorly, landing only a single thunk. Groans from some of the onlookers, but just as many whoops and cheers. It appeared Revellion had won. The young lord pranced forward to take a deep bow, earning polite applause from across the green as servants dashed out to collect the darts and flowers for another round.

She retrieved the sketch, sliding it into her pack and withdrawing a fresh sheet. This time she’d sketch the ladies, perhaps, a show of the latest fashions for—

She froze.

Across the green a trio of men made way toward her, drawing curious eyes from the nobles as they crossed the gardens. The three of them stood out among the nobles’ finery as sure as she would have done: two men in the blue and gold leather of the palace guard, one in simple brown robes. A priest.

Not all among the priesthood could touch the leylines, but she wouldn’t have wagered a copper against this one having the talent, even if she wasn’t close enough to see the scars on the backs of his hands to confirm it. Binder’s marks, the by-product of the test administered to every child the crown could get its hands on. If this priest had the gift, he could follow her tethers whether he could see her or no.

She scrambled to return the fresh page and stow her charcoals, slinging the pack on her shoulder and springing to her feet.

Time to go? Zi asked in her thoughts.

She didn’t bother to answer. Zi would keep up. At the edge of the green, the guardsmen patrolling the outer gardens turned to watch the priest and his fellows closing in. Damn. Her Faith would hold long enough to get her over the wall, but there wouldn’t be any stores to draw on once she left the green. She’d been hoping for another hour at least, time for half a dozen more sketches and another round of games. Instead there was a damned priest on watch. She’d be lucky to escape with no more than a chase through the woods, and thank the Gods they didn’t seem to have hounds or horses in tow to investigate her errant binding.

Better to move quickly, no?

She slowed mid-stride. “Zi, you know I hate—”

Shh.

Zi appeared a few paces ahead of her, his scales flushed a deep, sour red, the color of bottled wine. Without further warning her heart leapt in her chest, a red haze coloring her vision. Blood seemed to pound in her ears. Her muscles surged with raw energy, carrying her forward with a springing step that left the priest and his guardsmen behind as if they were mired in tar.

Her stomach roiled, but she made for the wall as fast as her feet could carry her. Zi was right, even if his gifts made her want to sick up the bread she’d scrounged for breakfast. The sooner she could get over the wall, the sooner she could drop her Faith tether and stop the priest tracking her binding. Maybe he’d think it no more than a curiosity, an errant cloud of ley-energy mistaken for something more.

She reached the vines and propelled herself up the wall in a smooth motion, vaulting the top and landing with a cat’s poise on the far side. Faith released as soon as she hit the ground, but she kept running until her heartbeat calmed, and the red haze faded from her sight.

The sounds and smells of the city reached her before the trees cleared enough to see it. A minor miracle for there to be trees at all; the northern and southern reaches had been cut to grassland, from the trade roads to the Great Barrier between the colonies and the wildlands beyond. But the Duc-Governor had ordered a wood maintained around the palace at Rasailles, and so the axes looked elsewhere for their fodder. It made for peaceful walks, when she wasn’t waiting for priests and guards to swoop down looking for signs she’d been trespassing on the green.

She’d spent the better part of the way back in relative safety. Zi’s gifts were strong, and thank the Gods they didn’t seem to register on the leylines. The priest gave up the chase with time enough for her to ponder the morning’s games: the decadence, a hidden world of wealth and beauty, all of it a stark contrast to the sullen eyes and sunken faces of the cityfolk. Her uncle would tell her it was part of the Gods’ plan, all the usual Trithetic dogma. A hard story to swallow, watching the nobles eating, laughing, and playing at their games when half the city couldn’t be certain where they’d find tomorrow’s meals. This was supposed to be a land of promise, a land of freedom and purpose—a New World. Remembering the opulence of Rasailles palace, it looked a lot like the old one to her. Not that she’d ever been across the sea, or anywhere in the colonies but here in New Sarresant. Still.

There was a certain allure to it, though.

It kept her coming back, and kept her patrons buying sketches whenever she set up shop in the markets. The fashions, the finery, the dream of something otherworldly almost close enough to touch. And Lord Revellion. She had to admit he was handsome, even far away. He seemed so confident, so prepared for the life he lived. What would he think of her? One thing to use her gifts and skulk her way onto the green, but that was a pale shadow of a real invitation. And that was where she fell short. Her gifts set her apart, but underneath it all she was still her. Not for the first time she wondered if that was enough. Could it be? Could it be enough to end up somewhere like Rasailles, with someone like Lord Revellion?

Zi pecked at her neck as he settled onto her shoulder, giving her a start. She smiled when she recovered, flicking his head.

We approach.

“Yes. Though I’m not sure I should take you to the market after you shushed me back there.”

Don’t sulk. It was for your protection.

“Oh, of course,” she said. “Still, Uncle could doubtless use my help in the chapel, and it is almost midday …”

Zi raised his head sharply, his eyes flaring like a pair of hot pokers, scales flushed to match.

“Okay, okay, the market it is.”

Zi cocked his head as if to confirm she was serious, then nestled down for a nap as she walked. She kept a brisk pace, taking care to avoid prying eyes that might be wondering what a lone girl was doing coming in from the woods. Soon she was back among the crowds of Southgate district, making her way toward the markets at the center of the city. Zi flushed a deep blue as she walked past the bustle of city life, weaving through the press.

Back on the cobblestone streets of New Sarresant, the lush greens and floral brightness of the royal gardens seemed like another world, foreign and strange. This was home: the sullen grays, worn wooden and brick buildings, the downcast eyes of the cityfolk as they went about the day’s business. Here a gilded coach drew eyes and whispers, and not always from a place as benign as envy. She knew better than to court the attention of that sort—the hot-eyed men who glared at the nobles’ backs, so long as no city watch could see.

She held her pack close, shoving past a pair of rough-looking pedestrians who’d stopped in the middle of the crowd. They gave her a dark look, and Zi raised himself up on her shoulders, giving them a snort. She rolled her eyes, as much for his bravado as theirs. Sometimes it was a good thing she was the only one who could see Zi.

As she approached the city center, she had to shove her way past another pocket of lookers-on, then another. Finally the press became too heavy and she came to a halt just outside the central square. A low rumble of whispers rolled through the crowds ahead, enough for her to know what was going on.

An execution.

She retreated a few paces, listening to the exchanges in the crowd. Not just one execution—three. Deserters from the army, which made them traitors, given the crown had declared war on the Gandsmen two seasons past. A glorious affair, meant to check a tyrant’s expansion, or so they’d proclaimed in the colonial papers. All it meant in her quarters of the city was food carts diverted southward, when the Gods knew there was little enough to spare.

Voices buzzed behind her as she ducked down an alley, with a glance up and down the street to ensure she was alone. Zi swelled up, his scales pulsing as his head darted about, eyes wide and hungering.

“What do you think?” she whispered to him. “Want to have a look?”

Yes. The thought dripped with anticipation.

Well, that settled that. But this time it was her choice to empower herself, and she’d do it without Zi making her heart beat in her throat.

She took a deep breath, sliding her eyes shut.

In the darkness behind her eyelids, lines of power emanated from the ground in all directions, a grid of interconnecting strands of light. Colors and shapes surrounded the lines, fed by energy from the shops, the houses, the people of the city. Overwhelmingly she saw the green pods of Life, abundant wherever people lived and worked. But at the edge of her vision she saw the red motes of Body, a relic of a bar fight or something of that sort. And, in the center of the city square, a shallow pool of Faith. Nothing like an execution to bring out belief and hope in the Gods and the unknown.

She opened herself to the leylines, binding strands of light between her body and the sources of the energy she needed.

Her eyes snapped open as Body energy surged through her. Her muscles became more responsive, her pack light as a feather. At the same time, she twisted a Faith tether around herself, fading from view.

By reflex she checked her stores. Plenty of Faith. Not much Body. She’d have to be quick. She took a step back, then bounded forward, leaping onto the side of the building. She twisted away as she kicked off the wall, spiraling out toward the roof’s overhang. Grabbing hold of the edge, she vaulted herself up onto the top of the tavern in one smooth motion.

Very nice, Zi thought to her. She bowed her head in a flourish, ignoring his sarcasm.

Now, can we go?

Urgency flooded her mind. Best not to keep Zi waiting when he got like this. She let Body dissipate but maintained her shroud of Faith as she walked along the roof of the tavern. Reaching the edge, she lowered herself to have a seat atop a window’s overhang as she looked down into the square. With luck she’d avoid catching the attention of any more priests or other binders in the area, and that meant she’d have the best seat in the house for these grisly proceedings.

She set her pack down beside her and pulled out her sketching materials. Might as well make a few silvers for her time.

14th Light Cavalry

Gand Territory

Over there, you see it?” one of her lance-corporals whispered.

“There, in front of the trees.” A soldier beside him pointed.

More excited whispers.

Erris snapped her fist up, signaling quiet in the ranks. She saw it. At the base of the forested hill she’d managed to sneak her men up during the night: a faint shimmer in the air, facing away from her soldiers, toward where she’d camped the night before. It meant the enemy had a binder skilled enough with Shelter to weave a shield against her attack.

And it meant their commander was a fool.

This flanking maneuver was far from her finest work. Simple. A child should have seen it. Anger flared, to think those poor soldiers at the base of the hill had to suffer under the command of an imbecile. Well, they wouldn’t have to suffer much longer.

“Draw sabers,” she whispered. “One volley with sidearms, then give them steel. Keep it quiet. Pass the order.”

Her command flew from soldier to soldier down their line, accompanied by the muted shink of cavalry sabers. She signaled to the horse-sergeants to stay in the rear with their mounts. The hill’s sloped angle and thick foliage wouldn’t allow a charge on horseback. Was that why the enemy commander was such a buffoon? Was he one of those who thought cavalry must stay mounted, that putting his soldiers’ backs to terrain impassable to horse rendered them impervious to her attack?

She spat.

A raised saber served to give the order, and she wheeled it forward to indicate a charge. As one her men surged over the brush and rocks they’d hidden behind.

A light rain began to fall, mixing with blood and gunfire as the sounds of battle rang through the trees.

“Hold still, damn you,” one of her sergeants cursed. “The brigade-colonel is on her way.”

“She’s arrived, Sergeant,” Erris replied, dropping to a knee. The soldier being held down by his squad commander stared through them both as he moaned. Young. Fresh-faced and clean-shaven, with eyes like saucer plates, filled with the horror of coming face-to-face with death for the first time.

The sergeant edged forward to make room for her at the boy’s side, losing his grip on an arm. She had to duck backward to avoid being taken across the side of her face as the wounded soldier flailed.

“Easy, son,” she said, moving to place her hands on his chest as she pulled off her gloves, exposing the binder’s marks on the backs of her hands. “I’ve seen worse than you this morning.” She had. The boy’s wound was among the least severe to be judged worthy of her attention. A musket ball that, from the thin streams of blood, had missed his major arteries. He might have been fine in due time without her, though Gods be damned if she’d let her men roll the dice and recover without her intervention.

The boy seemed not to hear, his rapid breathing punctuated by gasps and unintelligible muttering. She inhaled deep, closing her eyes. The green pods of Life energy were abundant in the wild, pooling in clouds beneath the elms and oaks, where fallen leaves and broken brush gave refuge to wildlife hiding from the sounds of battle. She tethered a strand between the boy and one of the nearby leylines. Not half so effective as if he could hold a binding on his own, and the barest sliver of what a fullbinder like Erris could do. But it would suffice.

“There you go,” she said. “Easy.” The boy sucked in air as energy coursed through him, giving his body strength to deal with the pain. For the first time since her arrival his eyes came into focus. He was one of the new recruits, freshly conscripted from the southern colonies before they crossed the Gand border. Seventeen if he was a day, tempted by the glory of honorable battle against the enemies of the crown. Six months ago he might have had a season’s training, drilling under the watchful eye of foul-mouthed instructors, before they put him in the saddle. But they were at war now, and the army took what it could get.

“Thank you,” the boy whispered hoarsely.

“You’ll be fine, son.” She patted his shoulder as she stood. “Listen to your squad commander and you’ll be riding again within a day or two.” He sputtered a cough, nodding as he closed his eyes.

The sergeant laid the boy down and rose to his feet with a hasty salute, fist to chest.

“Thank you, sir,” he said. “Shudder to think what we’d do without you.”

“Feed the worms, I expect, Sergeant,” she said with a smile, eliciting a nervous laugh from the man. A fullbinder with Erris’s strength was a rare thing. The medics did their best with the supplies available to the army, but her gifts had kept the 14th Light Cavalry on its horses throughout this campaign, and her men knew it as well as she did.

She returned the sergeant’s salute and left him to tend to his squad. One never got used to the smell of blood on this scale, the sounds men made as they lay dying. Lines of prisoners marched beside her, prodded by saber or carbine toward the field where her men had started to gather, away from the carnage of the fight. A skirmish, really. Two brigades colliding away from the trade roads. Little chance of any glory, or of seeing the battle named in the colonial papers. Such was the lot of the cavalry. Men with noble titles and fat purses declared wars for the glory of king and country, and her men did most of the dying, far away from medals, in backwoods and countryside left untouched in better times.

Six months, now, since the crown had declared its war on Gand, and expected its colonies across the sea to follow suit. A means to check the enemy’s expansion, according to the pamphlets circulated to justify the invasion, though Gand had not been alone in its drive to empire. Conquest and colonies brought the great powers gold and trade, but more important, discoveries of new bindings. The academics had argued larger claims of territory led to a stronger leyline grid, able to retain a broader spectrum of energies and bolster the gifts of those who could tether them. It had proven true enough, even in her lifetime. The Thellan War, five years before, had resulted in a select few of Sarresant’s binders gaining access to Entropy. No way of telling what a successful campaign against Gand would bring. And not her place to speculate. It was for men two hundred leagues north, in the palaces and manors of New Sarresant, Rasailles, and Villecours, or two thousand leagues across the sea, to dream up reasons to fight. Enough for her that the red-coated soldiers wanted her men dead, and it took killing them to keep her boys alive.

Her aide stood a few paces up the hill, waiting for her to finish reviewing the wounded. Sadrelle was a good man, a veteran of the autumn campaign who’d proven himself as a scout. Newly promoted to his lieutenant’s stripe, but that was the way of things during war. Her last aide had run afoul of a Gand sharpshooter, so now she had Sadrelle.

He made a salute as he fell into step beside her.

“Sir. Lance-Captain d’Guile has the prisoner you asked for. And the medics sent the bill.”

“How bad is it?”

“Fourteen dead. Six more critical beyond your aid. Thirty-six wounded and recovering.”

She cursed under her breath. A light toll, considering the forces had been almost evenly matched. But even a light toll weighed heavy on her shoulders. The soldiers trusted her with their lives; every mistake was paid in blood. Twenty dead, or would be soon enough.

“Thank you, Aide-Lieutenant. See to it the supply wagons arrive on the double. I need our wounded ready to travel within the half hour.”

“I’ve already sent word, sir.”

“Good.”

They walked on in silence, making their way back to the impromptu command post where her officers had placed her flag. Let the men see her, poised and outwardly confident, the very image of a brigade-colonel in her moment of victory. Inside her stomach roiled. Five hundred and seventeen souls in the 14th now. The Nameless take the butcher and his bills.

At the base of the hill, a double line of empty-saddled horses trotted into view. The horse-sergeants must have led them around the back of the approach as soon as she gave the order to charge. A confident move, approaching hubris. What if it had been a trap? She made a mental note to dress the handlers down that evening. She was not infallible as a commander, no matter what her men liked to think.

The men around the command post saluted her approach, all save a slumped figure at their center.

“What do we have, Lance-Captain?” she asked. Lance-Captain d’Guile had command of one of her four fighting companies, five hundred horse at full strength, though the 14th hadn’t been close to full strength in some time.

“A lieutenant, sir. Second in command of a company of infantry. Says they were with the Second Army, under Duke Dunweir.”

She raised an eyebrow. A lieutenant, the highest-ranking officer among those who hadn’t fled or been slain in the fighting. And 2nd Army. That was damned curious. The prisoner had lines under his eyes, dust smeared in ink-black patches on his skin as only a forced march could do. He’d been driven hard, perhaps a week or more of dawn-to-dusk marches without the benefit of a horse or a binder to spell his fatigue. What was the Gand 2nd Army doing so far north?

“Let’s see what he has to say.” She nodded to Sadrelle, who among his other talents had a near-perfect command of the Gand tongue. Her own ability with the language was not poor, but it wouldn’t do to have a Sarresant commander stutter over simple questions when interrogating a prisoner. “Ask him to repeat his rank and designation, for my sake.”

Sadrelle relayed her question in the harsh, chopped speech of the Gandsmen and the prisoner raised his head, looking her in the eyes as he responded. She gave the lieutenant full marks for bravery. Enemy he may be, but this man was no coward.

“Lieutenant Alistair Radford,” the prisoner said in the Gand tongue, voice straining with a mix of pride, fatigue, and resignation. “Second to Major Stuart, third company of Colonel Hansus’s regiment, Second Army under his excellency the Duke of Dunweir.”

“And what were your orders on this march, Lieutenant? Why was your regiment split from the main body of the Second Army?” Sadrelle relayed the message.

The prisoner stared at her.

She held his gaze, maintaining calm in her eyes as she spoke. “Tell the lieutenant his cooperation will determine whether he dines with Colonel Hansus in a fortnight or I put him and his fellow soldiers to the sword. He knows a cavalry unit isn’t going to march prisoners behind our supply wagons.”

Silence hung in the air after Sadrelle finished the translation. At last, the prisoner spoke. “Colonel Hansus is dead,” he said bitterly. “I stood beside him as he fell.”

She dropped to a knee and replied in Gand tongue herself. “Then you know what to do. Your men need you. Don’t fail them.”

The prisoner held his silence for a few more moments, then hung his head as he began to talk.

Half an hour later, she sat astride Jiri, issuing her final commands before they moved. A blessing from the Gods to be with her mount once more. Jiri whickered, bobbing her head up and down, and she patted the white mare’s neck in a calming gesture. Just as Erris worried for her soldiers, she knew Jiri worried for her. They were a pair; such was the nature of the bondsteed’s training, though no few of the prisoners cast dubious glances toward the figure she cut on Jiri’s back. Erris was not a tall woman, nor thickly built. Her blue cavalry uniform had to be specially sized for her frame, as did the long steel saber she wore on her belt. Jiri on the other hand would never be mistaken for anything other than what she was. Nineteen hands high and finely muscled despite her size, Jiri towered over any other horse on the 14th’s rope lines. Her training as a bondsteed—the formal name for mounts accustomed to bindings from their riders—only added to a strength and grace that would have made her an armored charger a few centuries before.

Erris maintained a simple binding of Life energy to keep their senses sharp. Her men had made quick work of preparing for the day’s ride, and if the weather permitted they would cover thirty leagues before sundown. A hard ride made harder for having started the day with bloodshed, and another fifty leagues tomorrow, Gods and the weather permitting. Enough to reach the main body of the Sarresant army, to deliver the prisoner’s information with time to act, if the bloody fools at high command took it for what it was.

The captured subcommander of an infantry company couldn’t know the gravity of what he’d revealed. But if Duke Dunweir’s 2nd Army was committed to a march into the Sarresant colonies, it could only mean the Gandsmen were trying a desperate gambit, leveraging their superior numbers for a hammer strike at New Sarresant itself. A gambit that might have gone undetected if Colonel Hansus’s regiment hadn’t taken the wrong fork two days past and stumbled into her patrol sweep.

Dumb luck. Or a trap. She couldn’t rule out either, in the military. Amusing just how thin the line could be between genius and idiocy.

She nudged Jiri forward with her knees, riding to the front of the column.

“Sure we can’t talk you out of this, sir?” d’Guile asked, a wry grin on his face.

She heeled Jiri to a stop beside them. “No, Captain; the order stands. You are to ride for the main body of the army in all haste. Relay what we’ve learned to high command. I’ll be along within a few days to confirm with a visual report.”

Lance-Captain Pourrain coughed politely beside her. “Colonel, with respe

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...