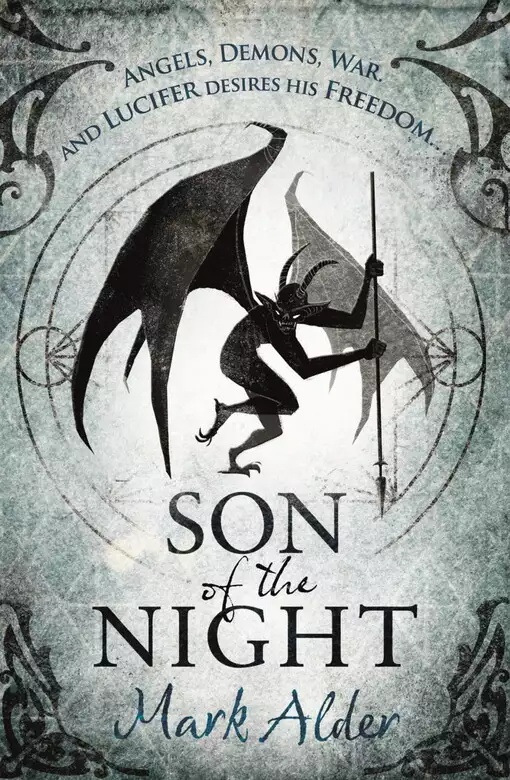

Son of the Night

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Following on from the success of Son of the Morning, which saw him compared to both Bernard Cornwell for the flair of his historical writing and to George RR Martin for his gripping plotting, Mark Alder takes his history of the 100 years war into France as the war between Heaven and Hell swallows up the ambitions of both the French and English crowns. As the armies mass around Crecy the rivalries between Lucifer, Satan and God become ever deeper and more violent. Combining a cast of larger than life (yet real) characters and a truthful, deeply researched take on the religious beliefs of the time Mark Alder is embarked on a truly unique historical fantasy that will ensure you never see the 100 Years War and the history of medieval Europe in the same way again.

Release date: August 24, 2017

Publisher: Gollancz

Print pages: 433

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Son of the Night

Mark Alder

The late summer morning was pleasant, the dew still on the grass outside the great church, the sun calling light from the wet land. He did not want to go. This was a blessed land, its people’s fingers stained yellow with the saffron they picked, the bees ambling among the flowers that grew from the turfed roofs of the cottages, the children fat and bonny.

‘Why must kings want things?’ Gâtinais asked his son Michel. ‘Why must they move and change? Why not doze through life, by the sun in summer, by the fire in winter?’

‘The English king wants our lands.’

‘Not our lands. Aquitaine, a little around Calais.’

‘Granted those, he will look for more.’

‘I suppose you’re right.’

He patted his horse’s neck. It was a good horse, a courser he’d ridden on many a pleasant ride through the gentle fields around his castle. He didn’t want it shot, spiked by English arrows, blown to bits by their guns or, worse, devoured by devils or demons or whatever strange infernal creatures the English had struck bargains with now.

‘We have displeased God by allowing the English to prosper in France,’ said Michel.

‘How do you know? Wouldn’t it please God more just to make a truce? Turn the other cheek and all that.’

‘Those that turn the other cheek get kicked twice in the arse.’ Robert, big burly Robert who’d nearly killed his mother coming into the world, smiled down at him, a head taller than his father. The boy was a credit, it had to be said. He favoured the war axe over the sword and was famous for his skill.

‘Blasphemy, boy, blasphemy.’

‘Less blasphemous than to allow the English and their devils to burn our churches, steal the relics of our saints.’

‘Indeed. You’ve had your axe blessed?’

‘And my armour, my dagger, my shield and my cock.’

‘You’re going to kill a devil, not swive one, brother,’ said Michel.

‘It’s the bit I’d like least to lose.’

‘Why?’ said Gâtinais. ‘You have four fine boys. One of them will make it to succeed you. Why do you need it more than your arm?’

‘For fun, Father.’

‘Oh, that,’ said Gâtinais. ‘All sounds rather tiring to me.’

‘My Lord Gâtinais!’

Pushing through the crowd that surrounded the war party, through the villeins at the back, the merchants in front of them, through the wealthier peasants in front of them, the clergy in front of them and the wives and young children of the nobility at the very front, were two men. The first was tall and gangling and wore a paint-spattered felt cap. The second could only just be seen behind him. A short, squat man who looked as though a giant had pressed a thumb on top of his head before his face was quite set.

For an instant Gâtinais thought the short man might be a devil. He’d had the borders of his land blessed but they covered a huge area and he was aware there was only so much blessing even the most hard-working priests could achieve. Then he recognised the tall one. A man who had been doing a little business for him.

‘Gâtinais! Noble Gâtinais!’ said the tall man.

‘Do not address yourself to the lord so boldly!’ A man-at-arms pointed towards the man.

‘Tancré?’ said Gâtinais.

‘It’s me, Lord, Tancré, at your service.’

‘Approach me, approach me.’

The crowd parted and the man came forward. He was dressed in a tunic that might once have been quite fine but now looked as though it had lain a while on the floor of a chicken house. The fellow beside him, he led by the hand. He was barelegged and barefooted, just a long tunic to cover him – a piece of rough cloth with a hole for the head, no more. A few in the crowd threw insults and made jokes as Tancré raised the man’s hand to display him to the lord. The people loved a simpleton and this man clearly appeared to be one.

‘I have him, sir – Jean the Idiot.’

‘We already have a fool, father,’ Robert spoke.

‘This man isn’t a fool, he’s a simpleton.’

‘There’s a difference?’

‘Yes – what kind of idiot are you?’

‘I thought the question was “What kind of idiot is he?”’ Robert laughed. He liked jokes like that.

‘A useful one. Try to copy his example.’ Gâtinais gave his son a wink and then dismounted.

‘Hold a while,’ he said. ‘I have an hour’s business to attend to.’

‘I can never guess summer hours. How long are they?’ asked Michel.

‘Long enough to have a drink,’ said Robert.

‘You might want to come with me,’ said Gâtinais.

Gâtinais led the two low men to the entrance of the great church. His sons followed on, with country folk’s easy disregard for the privileges of rank that said they should enter the church before the paupers.

‘This is the man?’

‘Yes, sir. He restored the windows at Lafage after the mob smashed the church.’

‘When did that happen?’ said Robert.

‘A while ago,’ said Gâtinais. ‘The low men in that area had an outbreak of the Luciferian disease. They set themselves about their masters!’

Robert crossed himself. ‘God save us from that.’

‘He has done,’ said Gâtinais. ‘Good masters need not fear men trying to upend God’s order. I am your protection.’ He turned to Tancré. ‘Didn’t the men of Lucifer burn half that church?’

‘They did, sir. But he rebuilt the window out of the heat-cracked pieces. He has a gift for it, sir. He is blessed by God to do His work.’

‘Another one?’ said Gâtinais. ‘Him and half the world nowadays, it seems, if you believe them.’

‘You can believe him, sir.’

From the darkness of the church porch a figure took form, black against the summer light. A priest.

‘Ah, Father,’ said Gâtinais. ‘I have a present for you.’

The priest, a man who had done his best to bring severity and penance to the jolly county of Gâtinais but had largely given up owing to the abundance of very good mead, smiled.

‘Sir?’

‘Explain, Tancré.’

The priest gave Tancré the sort of look he normally reserved for peasants caught shitting in the apse – a look he had to employ far too often for his liking – but inclined an ear anyway out of deference to his count.

‘My great Lord,’ said Tancré. ‘This is the man who can fix your window.’

The priest looked around him, at something of a loss.

‘What window?’

‘I thought you’d ask that,’ said Gâtinais.

‘You were correct, My Lord. Our windows seem to be in an excellent state of repair.’

‘Not the bricked-in one behind the altar.’

‘I feel that was bricked in for a reason. The church sits with the altar facing west. It’s confusing for the parishioners to see the evening light behind it.’

‘It was bricked in because a devil flew through it!’ said Gâtinais. ‘The count of Anjou’s wife, mother of the Plantagenets!’

‘That is an old legend spread by the enemies of England to discredit its royal line.’

‘I’m an enemy of England, and I don’t remember spreading it,’ said Robert.

‘Did it not perform miracles, this window, before that?’ said Gâtinais.

‘So it is said.’ The priest gave an exaggerated shrug. ‘The glass fragments certainly work none.’

‘No, but they might were they restored.’

‘No one even knows what it looked like.’

‘The idiot doesn’t need to know, sir,’ said Tancré. ‘He has a feel for it. He’s your man to repair anything broken.’

‘Set him to repair France,’ said the priest. ‘We have had enough of miracles. There are Devils abroad. The English army bristles with them, so it’s said.’

‘We will raise our angels,’ said Gâtinais. ‘And that will be the end of English devils. Let him see the remnants of this window, priest. I may not be long for this world and I would like to leave something to it. The miracle window restored would be a fitting monument, I think.’

‘As you instruct, sire.’ The priest didn’t roll his eyes but only, suspected Gâtinais, because he was making the effort not to.

They followed the priest down the long apse of the church to a door by the side of a shrine to Mary.

The priest, rather sacrilegiously in the view of Gâtinais, took a small votive candle from the shrine and opened the door. They progressed down a dark and winding stair, the light bobbing before them.

‘The crypt?’ said Gâtinais, who had never been in this part of the church before.

‘A store,’ said the priest.

At the bottom of the stair was a short corridor with three doors coming off it.

‘Look away, common men,’ said the priest. Tancré and Jacques did as they were bid and the priest reached his hand into a crack in the wall to pull out a key. He used it to open the door to their right.

There was a waft of damp and the smell of long disuse as the door scraped open. The priest went within with the light.

‘Follow, follow,’ said Gâtinais, to the two common men, who were still looking away.

Inside was a large box, as long as a coffin but as wide again. It had a rough wooden lid on it, which the priest lifted away. It seemed to Gâtinais that the box was full of sparkling jewels, blue and amber in the candlelight. But among them he saw bigger pieces of what he knew to be glass.

‘This is no place to keep a holy window,’ said Gâtinais.

‘The remains of one,’ said the priest. ‘It’s said an angel stepped from this window and shattered it. God sundered it.’

‘I thought a devil flew through it.’

‘It was a long time ago,’ said the priest. ‘You believe what you like. As you can see it’s some way beyond repair.’

So it seemed. Though the odd larger piece remained, most of the window was in tiny bits, dust some of it. Perhaps it had been ambitious. He should have looked at the window as soon as Tancré had suggested restoring it. He’d been so busy, though, organising the response to the king’s call.

‘Not beyond repair, sir. I promised you.’

‘You are a miracle worker?’ The priest raised a doubtful eyebrow.

‘No, sir, but the idiot is. You watch. He can repair anything.’

‘Beautiful,’ said Jean. His voice was thick and guttural, a peasant to his core.

‘Anything beautiful,’ said Tancré. ‘Let him show you.

‘No,’ said the priest, as Gâtinais said ‘Yes’.

‘If it pleases you,’ said the priest, adjusting his opinion to match that of his lord.

Tancré gestured for Jean to take up a piece of the glass. Jean put his hand over the box, as if uncertain which to choose. Then he withdrew one of the larger fragments, a sliver of blue the length of a finger. He held it up to the candle.

‘What’s he doing?’ said the priest.

‘Looking at it,’ said Tancré.

‘I can see that.’

Jean reached into the box again. Once more his hand hovered and then he withdrew a piece the size of a thumbnail. He studied that too, holding it to the candle.

‘I don’t think we can let this fool go heating up this glass,’ said the priest. ‘In some senses it might be seen as a holy relic. In some senses—’

He stopped short. The idiot drew a line with the glass across the back of his hand, drawing blood. Gâtinais exchanged glances with the priest.

‘Is this devilry? Blood magic?’ said the priest.

‘No more than the Communion,’ said Tancré.

‘Blasphemy,’ said the priest, without any great outrage.

The idiot smeared the blood across the edge of the bigger piece of glass. Then he put the smaller piece to it, as if expecting to use the blood as glue. He folded his hand over the two pieces and said:

‘At times the enormity of my sins overcame me, and I sighed with confusion and wondered at the long-suffering patience and goodness of God. It seemed to me that I saw Him depute some good guardian to defend me from the attacks of the evil demons … Meditating often about this, I desired greatly to know the name of my guardian, so that I could, when possible, honour his memory with some act of devotion. One night I fell asleep with this thought and behold, someone stood by me saying my prayer was heard, and that I might know without doubt that the name I desired to know was Gabriel.’

‘God’s knees, what a mouthful!’ said Gâtinais.

A very strange thing happened. Gâtinais only had eyes for the poor man’s hands. The candle, the glitter of the glass in the box, the eyes and teeth of his companions, no longer seemed to shine from the darkness. Only the hands cupped a glow, as if concealing a taper, as if all the light in the little space had condensed into Jean’s hands. Jean opened his grip and the light expanded to fill the room again. The two pieces of glass were whole.

‘Swipe me!’ said Gâtinais.

‘It’s a marketplace conjurer’s trick, no more,’ said the priest.

‘Well if it is, it’s a blessed good one. Where did he learn to talk like that? I’ve never known anyone outside a monastery gabble on so.’

‘How did you do it?’ said the priest. ‘You could be tried for witchcraft.’

‘Not by me,’ said Gâtinais, ‘so not at all.’ The Church was always trying to encroach on the rights of the nobility, and trials for witchcraft were strictly a secular affair.

‘It’s the light, sir, he can use the light,’ said Tancré.

‘The light wants,’ said Jean.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ said the priest.

‘He knows what the light wants, sir, he always says so.’

‘More trickery. Mark me, Count, these men learn a few mystical lines that ensnare the credulous and use it to try to gull their way to fortunes. This is a trick, like the nut that vanishes.’

Gâtinais took the piece and studied it. It was whole, no line, no fracture, just a deep and perfect blue glittering in the candlelight.

‘Well, we’ll soon see, won’t we?’ he said. ‘Allow him to begin the repair. If he can’t do it, it will soon become obvious.’

‘And then?’

‘He’s either rewarded or—’

‘Cut off his hands?’ said the priest.

‘Let’s taste the ale before deciding it’s spoiled. Give the man a chance.’

‘You can’t let him go unpunished if he’s a fraud.’

‘No, no. But we think too much on harshness nowadays. Let us try to do a good thing.’

‘Is it a good thing to allow a fool to sully holy relics?’

‘Is he a fool?’

‘A man who has been taught to ape a few lines of his betters. You will suffer, man, when your tricks are exposed.’

Jean spoke:

Et in misericordia tua disperdes inimicos meos et perdes omnes qui tribulant animam meam quoniam ego servus tuus sum.

‘What, what?’ said Gâtinais.

The priest crossed himself.

‘A psalm,’ he said.

‘What the devil does it mean?’

‘Do you not know Latin?’

‘About as well as you know the use of lance and sword. Of course I don’t know Latin – what’s the use of you lot if the nobility are going to stick their heads into books?’

‘“And in thy loving kindness cut off mine enemies, And destroy all them that afflict my soul; For I am thy servant.”’

The idiot nodded and pointed. Clearly he didn’t mind making enemies of churchmen, which marked him out as an idiot indeed.

‘He has learned these things for the benefit of clergy,’ said the priest. ‘He seeks to be tried by a Church court rather than face the punishment due to him as a common man.’

‘Well, that alone means he’s not as green as he is cabbage-looking,’ said Gâtinais. ‘Let him try, priest. The country is full of devils, called by kings. Then there are the demons that whisper treachery in the ears of the poor. We have been lucky not to see these things amongst us. The window is a blessed object and would provide protection. Even word that it was being restored might keep dark forces away.’

The priest took up the piece of glass. ‘How long would this take?’

‘No more than five years, sir,’ said Tancré. ‘He is a marvellous fast worker.’

‘A blink,’ said Gâtinais, ‘a blink in the life of this great church. Let him try.’

‘How much does this rogue want paying?’

‘Food only, sir. I have come to a financial arrangement with the count. Food only. He will sleep in the church or where you tell him, it’s a more comfortable spot than any he has known.’

‘We’ll have to move good brick.’

‘He will screen the gap, sir.’

‘Come on,’ said Gâtinais. ‘If an angel dwelt in that window once, perhaps it could again.’

The priest handed the glass back to Gâtinais.

‘Very well, though it’s against my best instincts. I’ve seen enough marketplace conjurers and charlatans in my time. But if it’s only going to cost me some bread and ale, then let’s try. And if he doesn’t restore it, I have your permission to punish him?’

‘You churchmen are zealots for pruning a fellow, aren’t you?. Yes. Clip away if you must but give him a fair chance. Nothing before I return from the wars.’

‘And if you do not return?’

‘Then it shall fall to my sons to take my place.’

‘And if they do not return?’

‘Then God is gone from the world and we are all damned. Now let’s get back into the light. I have a useless king to follow.’

So saying, he turned to the steps, to lead his sons to war and all of their deaths on Crécy field.

The count of Eu pulled up the visor on his pig-faced helmet, wiped the smoke from his eyes and surveyed the disaster unfolding before him at Caen.

The English were massing all around the island town. He steadied his horse as a flight of ympes, tiny winged men no bigger than crows, swept over him, their swords and arrows like a glint of rain. By God, he was facing a strange alliance. The English, with their angel Chamuel, their hordes of devils under God and their swooping demons, the damned of Hell, servants of Lucifer. He thanked Christ he was French. Their army only contained angels and devils, who bowed the knee to God on high. But where were they? King Philip had to send an angel or a flight of stoneskins or something to help him. It was the king who had engineered this catastrophe in waiting.

Eu’s footmen massed against the barricade on the bridge, mail clashing against mail, lances bristling. Behind them priests sang blessings, swung incense burners, flicked holy water over the troops. A formidable force, but the bridge would not hold. None of the bridges would hold. The barricades had been built too hastily, too few and not substantial enough. He had two hundred men on every barricade and a further nine hundred spread along the banks of Caen. Not enough, not enough.

Over the broken body of a cart on top of the barricade rose a grinning skull atop a man’s body. The body was waving a sword. Later, he would know this to be one of the bone-faced men, 3rd Legion of the Devils of Gehenna. One of the many. His men jeered and jabbed at it but it was safely above their spears.

Soon, though, the barricades would be rendered useless. They’d had no time to remove the boats from the river banks. The English archers and men-at-arms were swarming into them, loosing arrows as they went, ducking beneath shields to avoid the returning fire. This was going to be a test.

He drew his own sword, Joyeuse, letting the blessed weapon’s light shine out. The sacred king Charlemagne had wielded that sword to build the empire of the Franks and to wet the desert with unbelievers’ blood and every Constable of France had borne it since. That gave the bone-faced man pause for thought and he ducked back behind the cart.

Robert Bertrand drew up beside Eu, magnificent on his white horse, his armour polished to brilliance, his surcoat embroidered with golden stars – almost an angel himself, he appeared.

‘Not good, Raoul,’ he said.

‘Not good,’ said Eu. ‘How many of them?’

‘Nine, ten thousand, excluding the diaboliques.’

‘Six to one.’

‘In the castle we could have held them.’

‘If my aunt had a dick, she’d be my uncle.’

‘We shouldn’t be on this island. Are we throwing away France to protect the plate of a few hundred grubby buyers and sellers? Men of trade? My God, what a pass we have come to?’

‘Apparently it’s God’s will.’

‘The will of Prince John!’

‘Same thing,’ said Eu.

He meant it, too. Given his choice Eu would have knocked down a few of the city’s houses and used the rubble to block the way. But no, strings had been pulled, favours called in. The town was to be defended unscathed. So instead of bogging the English down in a protracted siege, thumbing his nose at them from the island castle walls, that idiot Prince John had insisted he defend the second island of the town, to protect the merchants and their houses. He had told the messenger that he could protect the merchants but could not protect their houses. The prince had said that he could. Still, the prince was divinely appointed, his army backed by angels. To disobey him was to disobey God. So do and be damned, don’t do and actually be damned. The castle was now crammed with the rich and influential of Caen, while anyone who had any idea at all about how to actually conduct a siege was out in the streets waiting for the English to destroy them.

As constable, he had the right to be in the tower. He had given it up. If his men were to stand any chance at all he needed to be with them. The English angel had recognised his royal blood, agreed to hold back its fire until God made His will known in the direction of the battle. It was strange indeed to talk to that thing, an enormous shining man, armoured and shielded, floating above the parapets, its voice intoxicating, sending Eu’s head spinning. Eu had done his job, though, convinced it of his piety, or the sacrifices and godliness of the people of Caen, had asked it to look at the churches they had built, the art they had commissioned to God’s glory. It had lost interest in raining fire down on his men.

Where were his angels? Where were his devils? All with the main army. Couldn’t angels be anywhere? He’d heard it said. Well, if they could, they chose not to be at Caen.

An awful roar and the warhorse beneath him shivered. The English were discharging their cannon. Good. Those things were more of a peril to the men operating them than to his troops.

‘If I should die …’ said Bertrand.

‘What?’

Bertrand shrugged, his armour so well made that it moved on his shoulders as easy as a cloak.

‘It’s a possibility. Devils. These low men, these servants of Lucifer who travel with the English king. They cannot be relied upon.’

‘You’re not going to die, Robert, my God, you’re a marshal of France. Do you think the English have taken leave of their senses?’

‘I think some of them may never have had any. These are new times, Raoul. The old certainties of battle do not apply.’

A great cry from the bank. Their troops were showering arrows on the English, the English returning fire from the bank. A thud as an arrow glanced off Eu’s breastplate. He paid it no notice. There was no way an English bodkin would get through his armour at ten paces. At a hundred the arrows were but summer midges.

A great cry and a bristling mass of men came streaming into the barricade.

‘There’s one certainty,’ said Eu. ‘French knights fight harder than any devil. Your sword is blessed?’

‘Of course.’

‘Then let’s cry havoc and stain these streets with our enemies’ blood!’

Bertrand smiled. ‘I’ll see you in Heaven.’

‘More likely England,’ said Eu. ‘Though we may be in irons. Squires, attend me!’

His young knights closed in, his page Marcel running behind carrying a teeter-tottering lance so much bigger than him it was a wonder the boy could lift it. He was no more than nine years old.

‘Cheaper to get killed than pay your ransom!’ said Bertrand.

‘I’ll remember that when the English come for me! Hold the barricades! Hold them!’

Swarms of devils hit the bridges. Giant beetles winging in, bone-faced men crawling over the piled barricades, streams of stoneskins dropping boulders and logs. A volley of blessed arrows from his own men saw the flight of gargoyles turn. Over the river he could hear a terrible roaring. That was no cannon. He told his squires to stand where they were. He wheeled his horse down to the waterfront to see on the other bank a monstrous lion, erect like a man on its back paws. It wore dull grey armour and its mane was like a brush of steel rods. Lord Sloth, Satan’s ambassador. Eu had heard that good servant of God had thrown his lot in with the English.

His men were exchanging bow fire with the enemy, so he left his horse behind a house. Its caparison was thick but, at such range, the arrows might get through. He, however, was impervious in his armour.

He held up Joyeuse for the lion to see. Sloth roared again, its breath almost palpable across the river.

‘God’s sword!’ shouted Eu. ‘God’s wrath for you, Sloth!’

‘I serve Satan, and he serves God.’

‘We all say we serve God nowadays. Perhaps this battle will see who the Almighty favours.’

Arrows peppered the bank. ‘Your angel hasn’t engaged, Sloth. It seems it thinks the day is in question.’

‘I’ll give you question!’ roared the lion. ‘I’ll—’

A mighty noise, like a great sigh from behind him. ‘The East Bridge is lost!’ came a cry.

The lion turned away and ran along the riverbank.

Eu ran back, mounted and spurred his horse towards the fray.

His men were in flight, the low bowmen of Lucifer at their backs. The town was falling. He felt a delicious shiver go through him, like the first kiss of wine on a summer’s afternoon. Men like him were born for days like these. He held high his sword and trotted towards the foe, his knights falling in beside him, the fleur-de-lys fluttering from their pennants.

‘France! France!’ he screamed.

Men stopped, turned, their courage renewed by the sight of such a leader. How many English? It didn’t matter. The bridge was narrow, packed like a marketplace, the invaders disordered, bowmen, bone-faces and men-at-arms, not a lance among them. He levelled his sword and charged, six knights behind him, lances fixed.

Panic, utter and complete, as they hit the English line at the trot. Such a crush, such a glorious crush. My God, he caused his share of havoc but the English did the rest themselves, panicking, turning, trying to run over the barricade they had so recently overwhelmed, stamping down the fallen, tripping and being stamped. Such terror gripped them that they forgot to fight. His horse reared, but not in panic. Like him, it was trained for this. Its hoof came crashing down on a bone face’s skull, reducing it to powder. He’d had the animal’s shoes rubbed with the blood of St Cuthbert, an anathema to things of Hell.

Men hit the water, leaping for their lives. He cut and slashed, not really seeing who he hit, registering success by the judder of his sword. The charge had done its job, numbed minds, broken wills. The enemy didn’t even bother to fight. Yes, you can kill a warhorse if you hold your nerve and present your sword, but say your prayers, for they will be your last. The mind may cry hold but the heart screams run. Weapons were flung down, shields cast aside in the panic to be away.

‘To me, France! To me!’

His men followed his standard into the rabble, casting the English down, forcing them scrambling back across the barricades.

‘Reform the picket!’ shouted Eu. ‘They’ll not come so boldly again!’

Screams from behind. He wheeled. The shiny black beetle devils were engaging his men on the West Bridge, Bertrand’s white horse among them, death in a circle around it. Another roar from the East Bridge. Oh God, Sloth! He’d forgotten about him. And then a sound he had heard before but hoped never to hear again. People shut in burning buildings screamed like that, men on sinking ships. Something was coming across the North Bridge and his men, veterans of the English wars, were crying like children.

He spurred his horse towards the noise to find his troops in a mad flight. A noise like a monstrous drum. The shaking of the earth. A cry in an English voice:

‘“He moveth his tail like a cedar: the sinews of his stones are wrapped together. His bones are as strong pieces of brass; his bones are like bars of iron.”’

Eu lifted his visor to address the fleeing men.

‘What? What?’

No sense, just panic. Why were they running? There was nowhere to run to.

He rode on to the North Bridge. A shiny black beetle flew before him, big as a dog, flapping and biting but Joyeuse cut it down, its body smacking to the stones.

And then there it was, lumbering on, accompanied by priests, who chanted and sang. It was like an enormous man, four times taller than the biggest knight, fat as the elephant of legend and wielding a headsman’s sword, a long triangle, thick at the end. What strength did it need to swing that as a weapon? Its belly was huge and distended but ridged with muscle and a monstrous cock swung beneath its legs. Its upper body was bloated too – long arms as thick as trees. Its head was like a turnip, purple and yellow, a wide mouth full of cruel teeth. Behind it, cautious and creeping, was a mass of men-at-arms. Eu guessed the devil might not be too careful about who it swiped with that great sword.

‘Behemoth!’ it shrieked, its voice like the scream of a thousand birds. ‘Behemoth! I am sin’s reward!’

There were no defenders around

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...