- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

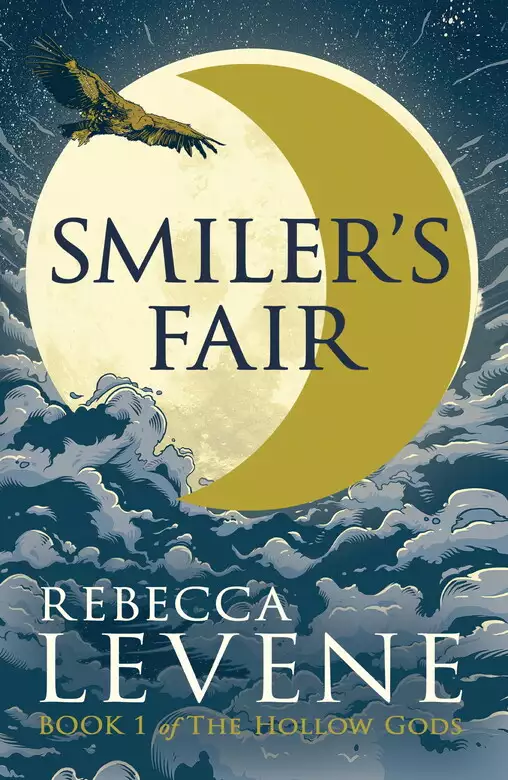

Yron the moon god died, but now he's reborn in the false king's son. His human father wanted to kill him, but his mother sacrificed her life to save him. He'll return one day to claim his birthright. He'll change your life. He'll change everything. Smiler's Fair: the great moving carnival where any pleasure can be had, if you're willing to pay the price. They say all paths cross at Smiler's Fair. They say it'll change your life. For five people, Smiler's Fair will change everything. In a land where unimaginable horror lurks in the shadows, where the very sun and moon are at war, five people - Nethmi, the orphaned daughter of a murdered nobleman, who in desperation commits an act that will haunt her forever. Dae Hyo, the skilled warrior, who discovers that a lifetime of bravery cannot make up for a single mistake. Eric, who follows his heart only to find that love exacts a terrible price. Marvan, the master swordsman, who takes more pleasure from killing than he should. And Krish, the humble goatherd, with a destiny he hardly understands and can never accept - will discover just how much Smiler's Fair changes everything.

Release date: July 31, 2014

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 375

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Smiler's Fair

Rebecca Levene

The room didn’t look like a prison. Her royal husband had been generous when he’d chosen her quarters and her chambers were in the oldest part of Ashfall, its ancient heart. The wooden walls were stained purple-red with grassweed and the tapestries over them showed scenes of the great ocean crossing, the smiling faces of their ancestors looking out from their ships towards the new lands. A thick rug covered the floor, giving her feet a sure grip as it rocked beneath her with the motion of the water. The windows were wide, letting in the weak winter sun and the not-quite-fresh smell of the lake.

The guards were out of sight outside the door, the door itself unlocked. But the guards were there and they wouldn’t let her leave, not while the baby remained inside her. She’d have her freedom again when her husband had taken his child’s life.

Athula huddled in the rocking chair opposite, a string of drool connecting her lips to her stained woollen dress. Samadara could see the meat knife at her belt. It was unremarkable and unthreatening, something the guards wouldn’t have thought to question. But if her maid had done as she’d asked, it would be sharp enough for the job.

‘Athula,’ she said, and again when the old woman’s eyes blinked open, ‘Athula, it’s time.’

The wrinkled face was hard to read. Was it pity Samadara saw there? Fear? Or perhaps those were her own feelings.

‘Are you sure, my lovely?’ Athula asked.

Samadara nodded. ‘The babe stirs – he’s eager for freedom. Soon Nayan will have his guards inside the room and there’ll be no saving him.’

‘Do you have to save him?’ Athula held up a hand when she would have protested. ‘Babies die every day, my duck. If your little mite comes into the world this way, he might live but an hour. It’s a high price for such a short time.’

‘I’ll pay it. Your man’s waiting outside as we arranged?’

‘And the guard has no eyes below, I’ve checked it myself. We’re ready, if you mean to go through with it.’

Samadara nodded. ‘Well then.’

Her body was ungainly, barely within her command in these last weeks of her pregnancy. She struggled with the front ties of her dress, her swollen fingers clumsy on the ribbons, but she batted Athula’s hands aside when the old woman tried to assist. She wanted her dignity now, or as much of it as her husband had left her. She let the servant help with her slippers, the barrier of her belly hiding even her own feet from her. She felt, more strongly than ever, that her body had been stolen from her, boarded like a river barge by brigands and forced to carry a cargo she had never sought. But though it wasn’t of her choosing, it had become more precious to her than she could have imagined.

Soon she was in nothing but her underdress. She hitched it over her hips and then sat on the edge of the bed to pull it over her head.

‘Here.’ Athula drew a flask from her apron pocket and offered it to Samadara.

‘You’re sure this won’t harm the baby?’

‘It might, my sweeting. It might. But screaming will harm him more, when the guards hear your cries and come to dash his head against the wall. Drink.’

The concoction was so sweet it almost gagged her, but she tipped the flask and drank it all. Its effects took only moments, a syrupy lethargy that was perilously pleasant. She nodded at Athula, fighting against her drooping eyelids. She wanted to be awake to see her son, at least once.

‘Ready?’ Athula asked.

She nodded again and her maid drew the knife. The blade was pitted but the edge was keen. Samadara watched as that gnarled hand rested it against the tight skin of her stomach. Her belly button protruded comically in its centre. She remembered the day it had inverted and how she’d thought about this moment and chosen it for her future. ‘Show me where you’ll cut,’ she said, suddenly desperate to delay.

Athula’s finger was cold as it traced an arc like the Smiler’s wicked grin the length of Samadara’s belly. ‘Here. It must be deep, but not too deep – I don’t want to be injuring the babe, now do I?’

Her touch tickled and Samadara squirmed away from it. ‘Yes. I see.’

There was no sound except the old woman’s harsh breathing as she pressed the blade more firmly against Samadara’s skin. The cut stung immediately and blood gathered into droplets along its length.

‘Finish it,’ Samadara said.

Athula grunted, clamped her hand across Samadara’s mouth and slashed the knife across her from hip to hip. Even with the sorghum juice inside her, the pain was deeper than she could have guessed and she screamed, her maid’s hand muffling the sound to a desperate whimper.

For a moment the cut was just a red line on her stomach. She watched with wet, shocked eyes as the line widened and then split, and the fat that lay beneath gleamed greasily for a moment before blood coated and hid it.

Athula smiled at her, perhaps encouragingly. Her broken teeth looked like old bones as she pressed her fingers against the gaping wound. The brown of her hand and the brown of Samadara’s stomach blurred together as tears misted her eyes and she realised that she was close to passing out.

Athula’s fingers clawed into the raw wound and pulled. Samadara tried to scream again and felt the horrible ripping as something tore. When she looked down, though, she saw that it had only been her skin. The cut was deep, but not deep enough. The welling blood was already beginning to clot and her babe still curled inside her, under a sentence of death.

She forced her eyes to remain open as Athula slashed the knife again, deep and hard. She was expecting the pain but it was less this time. Her mind seemed to overlook it, floating above her own body.

Her belly folded open and back. It looked like the flowers Lord Rajvir of Delta’s Strength had once sent her husband, the ones that smelled like rotted meat and trapped flies in their sticky petals. An evil mix of blood and darker fluids seeped from her stomach until Athula slashed the knife a third time and there was a gush of water, washing it all temporarily clean. And there he was, her son, his dark hair stringy and sparse.

The baby’s head poked grotesquely from her mutilated stomach. Her fingers tingled with fading sensation as she ran them over his soft scalp. She could see his little mouth, pursed like a rosebud. There was a smear of something over it and she realised that he wasn’t breathing and that this might all have been for nothing. ‘Help him,’ she gasped. ‘Please, Athula. Save him.’

Athula nodded, but her fingers fumbled against the slick blood coating Samadara’s son and his face grew bluer with every second.

‘Hurry, please. He’s dying.’

‘These old bones have lost their strength, my duck.’ But Athula’s grip tightened, and then she was lifting the babe clear of the wreckage of Samadara’s body and wiping his face clean with expert fingers

Samadara smiled to see his mouth open in a sudden, shocked gasp as he drew air into his body. Then his eyes blinked open and she was the one who gasped. His irises were silver, the unlucky colour of the moon, the pupils a vertical crescent within them that swelled into a dark sphere as her son looked at his mother for the first and last time.

‘He has the mark of evil,’ she whispered. ‘The prophecy was true.’

Athula walked the spiral corridors of the palace. She swayed with its gentle rocking and winced as the strain of staying upright set her knees to aching. The purple-red of the walls reminded her of her mistress’s body, spilling its insides out on to the bed. Her hands were still damp from washing the gore away and every time she passed a guard, she felt the sluggish beat of her heart quicken. But the alarm had not been raised and shouldn’t be for another hour; the guards only checked in on Samadara twice a night.

She thought of the woman she’d left behind, broken on bloody sheets. The death grieved her, of course it did, but the pain was a dull one. She’d done her mourning already, back when Samadara had first spoken of her plan. For the last few weeks when she’d looked at her mistress she’d seen a woman already dead.

The babe was what mattered now and he was safe, lowered in a basket to her son waiting below. They were to meet in the fallow barley fields beyond the rookery and then away, to the mountains and out of Ashanesland entirely. The heavy bag of gold wheels hidden beneath her dress would keep them as they raised King Nayan’s stolen son.

The spiral corridor opened into a broader one and to her left she saw the open space of the wheel room. The Oak Wheel sat at its head, the symbol of her sovereign’s power. She hurried past as quickly as she could, dropping her eyes from the carrion riders who slouched on guard outside the double doors.

The sanctuary was next, and she lingered there a moment to stare at the prow gods of the nation. She might offer a prayer for her success, but which of them would help her now? Lord Lust concerned himself with the making of babies, not their raising, and the Crooked Man healed the sick, not the newborn. There was the Fierce Child, perhaps, but he cared only for his beasts, and neither the Lady nor the Smiler had time for the life of one small child. Well, in some things the gods could help a woman, in all else a woman must help herself.

She sighed and shuffled on, through the painted library and the great dining hall lined with portraits of the little babe’s illustrious ancestors. Then there was daylight ahead and she was through the gates and at the foot of the bridge.

The 500-foot-long wooden span perched on top of the chains that linked the floating palace to the lakeshore. They were near the rookery now, as chance would have it, so she’d have to walk through the home of the carrion riders to reach freedom.

It did look a terrible long way. The inner bridge was shorter, but it led only to the island in the lake’s centre and the pleasure gardens that covered its conical peak. As a lass she’d often climbed its slopes to pick wild flowers with her swains.

The guards watched her incuriously as she began crossing the outer bridge. The musky odour of the mammoths reached her, the six hairy giants labouring in their traces to pull the weight of Ashfall along. The chains creaked and wavelets slapped against them as they moved, dragging the palace on its endless circuit of the lake. The walk was slow on her weak legs, but soon enough the shore came into sharper focus.

She turned for one last look at her home. Its wooden spires rose above the platform on which it floated, the paint that had once brightened them flaking and dull, as worn as her body. The pictures of lilies had decayed into leprous white splotches and the figures she remembered as proud guardsmen were faded to shades of themselves. They’d paint Ashfall again soon, as they’d last done in her twenty-third year, but she wouldn’t be there to see it.

The mammoth-masters smiled at her as she passed, touching their fingers to their foreheads. She smiled back and walked on. If all had gone to plan, her son was waiting for her. She looked for him, but the lake was littered with the craft of the landborn and it was hard to pick out his little skiff among them.

As she walked through the rookery, the cries of the carrion mounts sounded like warnings of ill-fortune, but when she finally reached the fields beyond, her son was there. The babe was tucked in a sling across his chest and her gut clenched as she thought of how many people must have seen him. They’d be certain to remember Janaka, who’d fathered no child but was carrying one on the very day the King’s cursed son was stolen from his mother’s womb.

It was too late now for such fears. She took Janaka’s hand and they walked together, along the bank of the river that gushed seaward from the lake.

‘He lives, then?’ She nodded at the bundle in her son’s arms.

‘He breathes. I gave him a drop of sorghum juice. I couldn’t have him cry out when I was on the boat.’

‘He seemed sickly to me. Too long without air, I’ve seen it before. Jamula’s lad never spoke more than five words, never grew in his mind more than a three-year-old, and he was blue at birth just like this one.’

‘I doubt he’ll live,’ Janaka said. ‘Even without the King’s men after him.’

Athula nodded and was surprised to find that they’d both stopped on the riverbank. The lively water rushed past beneath their feet. The purse felt heavy between her breasts, her skin warming the gold inside. She drew it out to show her son, and his eyes glittered as bright as the coins.

Janaka dropped to his knees and plucked a rounded rock from the mud, then another. ‘It’s hardly killing,’ he said. ‘The child was never meant to live.’

She stared at the bundle in his arms as he fixed the heavy rocks inside the swaddling clothes. It didn’t even really look like a baby. She’d only had one brief glimpse of the boy’s face and his strange eyes. Samadara was dead, and the child did have the mark of misfortune on him.

‘Well, Mama?’ Janaka asked. He was looking for her to take responsibility, and so she should. That was what a mother did for her son. It was what Samadara had done for hers, but Samadara was gone. This babe had killed her: he might as well have held the knife himself. Athula found that it was easy to hate him when she remembered her mistress’s mutilated, lifeless body.

She nodded. ‘He’s sickly – he’ll never live. Better to end it quick.’

She turned as the water swallowed the small, silent bundle and followed her son when he walked away.

If there had been just one thief, Krish might have tried running. But the moment he noticed the man ahead, lounging against a rock with his knife drawn and a stony look on his face, he heard the crunch of boots in shale behind him and turned to see the second.

The headman’s donkey, hired for the journey, raised his shaggy muzzle and brayed. Krish would have liked to do the same. He’d come all this way, three days down the mountain, along high, narrow tracks and through snowdrifts, and he hadn’t lost a single one of the hides and herbs and bone carvings his da had sent him to sell. And now this.

‘Going to Frogsing Village?’ asked the man in front, while the man behind sidled closer.

Krish nodded, lowering his head but not his eyes.

‘Trading?’

‘Hides.’ Krish saw no need to mention the other things, perhaps too small for the thieves to spot in the donkey’s saddlebags.

There was a moist hawking sound as the man behind spat. Krish realised his face was still pimpled and that he was no older than Krish; but they both outweighed him, and the second youth held an axe with loose strength. ‘We’ve no use for hides,’ he said. His voice was thick, as if his tongue was too large for his mouth. ‘It’s coin we want.’

‘I don’t have any money,’ Krish told him. ‘Not yet.’

‘Really?’ The first man closed his meaty hand around Krish’s left forearm and his friend took the other. They startled a little when they got a close look at Krish’s eyes but didn’t loosen their grip.

Krish knew he was shaking. He gritted his teeth so they wouldn’t chatter and said, ‘It’s true. I haven’t been to market.’

That seemed to give the thieves pause. The first released Krish to scratch a finger through his short hair. ‘Well,’ he said to his companion. ‘He is heading into the village.’

The doubt on their faces slowed Krish’s pounding heart a little. They were young and their weapons were flint like his own belt knife. They hadn’t managed to steal the coin to buy metal, which made them either inexperienced or inept.

‘I can tell you where you need to wait for other traders,’ Krish said. He pointed at a rock formation on the shoulder of the mountain, a twisted heart inside a brown ring. ‘See there, the grey boulder – another path runs beside it. This way is slow, for when the donkey’s carrying. That’s steeper but quicker. We take it when we’re going home.’ It might even be true. This was the first year his da had sent Krish down the mountain rather than going himself. Krish hadn’t yet figured out his route back, but he’d spotted the goat track he was pointing to and thought it hopeful.

The first thief was looking where Krish pointed, but the second’s gaze shifted over his shoulder, into the valley far below.

‘What is it?’ his companion asked.

‘It’s … I think …’ He walked forward, towards the lip of the escarpment. The other thief followed, his captive seemingly forgotten, and Krish thought he might stand a chance of slipping away. But now he could see what they’d spotted: a vast, complex collection of shapes in the distance, out of place against the brown mud and scattered trees of the valley. A dirty haze rose above it, circled by birds.

‘Is that Ashfall?’ Krish asked. He moved forward to stare between the two thieves.

‘Ashfall?’ the thick-voiced man scoffed. ‘We’re a thousand miles from Ashfall. Don’t you know nothing?’

‘That’s no shipfort,’ the other agreed. ‘It’s too big. And it weren’t here last week. You don’t know nothing, do you?’

‘Then what is it?’

‘That’s Smiler’s Fair,’ the thief said.

Nethmi paused fifty paces in front of the gates and grasped Lahiru’s arm tighter. His two guardsmen shuffled to a halt behind them, so close she could feel their garlicky breath against her neck. She knew they were gawping over her shoulder. She was gawping too. She’d heard of Smiler’s Fair, of course, but hearing and seeing were two different things. Now she was here, her uncle’s orders to stay away didn’t seem quite so unreasonable.

The gates were wood and twice as tall as a man. Through them she could see a broad street surfaced with straw and lined with buildings three, four and even five storeys tall, leaning perilously above the crowds. Further in there were taller spires yet, brightly tiled and hung with pennants whose designs she didn’t know: a fat, laughing man, dice and – she blushed and turned away – a naked breast. It was impossible to think that none of this had been here two days before. And the people. Tall, short, fat, thin, with skin and hair of every shade, a babble of languages and faces eager for the entertainments of the fair. It was hard to imagine herself a part of that crowd, swept along in its dangerous currents.

‘What’s that stink?’ one of Lahiru’s armsmen asked.

‘It’s the smell of everything,’ Lahiru said. ‘They say the fair holds one example of all that there is in the world – every food, every spice, every pleasure and every vice.’

‘And the virtues?’ Nethmi asked.

He grinned, not seeming to share her fear. ‘The fair’s only interested in what it can buy and sell. There’s no profit in virtue. Come, you’ll see when you’re inside.’

He pulled on her arm and she let herself be led. This might be the last day she ever spent with Lahiru, and she was determined to enjoy it. So what if her uncle had forbidden her to come here? Last night he’d told her of the marriage he’d arranged for her, a match to Lord Thilak of Winter’s Hammer in the distant and cold west. It was just three weeks until she went from her home to that lonely place.

Her uncle had given her no choice, only a portrait of her betrothed so she could grow accustomed to his face. Lord Thilak looked handsome enough, with thick hair and smiling eyes, but shipborn painters were paid to flatter. She’d seen her own portrait and while it had captured her doll-like prettiness with reasonable accuracy, she knew her nose wasn’t quite so straight nor her lips so full and red. And Thilak was old, approaching fifty. What kind of husband could he be to her? But there was no use dwelling on her situation. There was nothing she could do about it – only this petty act of rebellion, which would have to be enough.

The entryway to the fair was thronged with the landborn, but Lahiru’s men shouldered a way through so they soon came to the gate and those guarding it. Nethmi couldn’t help but stare. She’d seen Wanderers before, with their strange pale skin, but these men were odder yet. Their hair was gold and silk-fine, their limbs were wrapped tight in cloth of the same colour and they were as tall and slender as the spears they held crossed to bar the way.

‘Halt, stranger,’ one said, ‘and speak your name.’

Lahiru stepped forward confidently. ‘I am Lahiru, lord of Smallwood, and this is the Lady Nethmi of Whitewood.’

‘And those?’ the man asked, nodding at the guards.

‘Saman and Janith, also of Smallwood.’

Nethmi saw the other pale man carefully writing the names on his tablet, and then the spears were uncrossed and they were waved through. The smell was stronger and ranker inside, and the noise almost overwhelming. She held fast to Lahiru, an anchor in the tide of people washing down the thoroughfare. A goose honked at her and chickens flapped their wings from the doorway of one house while their brethren boiled in great tureens opposite. White-coated men ladled the broth into bowls and passed them out to anyone with the coin.

‘Why do they need our names? Will they report us?’ she asked Lahiru.

He shook his head. ‘It’s for their own use, not to be passed on. They keep a record so they can tell if anyone is missing. You’ll be asked again at each gate between districts, if I recall. Each company keeps its own records of who’s come and gone and a roll-call is taken every morning.’

‘But why?’

‘Well … So they know if the worm men have eaten anyone in the night.’

‘The worm men?’ She stared at him to see if he was teasing.

‘They believe so, yes. It’s how the fair knows when it’s time to move on. The worm men fear the sun—’

‘In children’s stories!’

‘The citizens of the fair believe them to be true,’ Lahiru replied, herding her away from a donkey cart and into the path of a juggler, who cursed as his batons and balls dropped all around him. ‘They believe the sun poisons the land against the worm men so they can’t emerge from their lairs below. But as the weeks pass and the fair keeps the soil in permanent shadow, the influence of the sun fades until the monsters are able to dig to the surface and snatch a victim. And when the first death comes, Smiler’s Fair breaks its pitch and travels on.’

‘But …’ Nethmi looked around. They’d moved deeper into the fair as they talked, into a region of narrow alleys and houses open on their lower floors to reveal stalls selling jewellery and cloth and spices and weapons and other objects whose use she couldn’t guess. They passed a tall, narrow house whose walls were covered in slippers of every shade, another filled with silver teapots and delicate glasses and a third whose walls of empty-eyed masks made Nethmi turn away uneasily. The stalls’ owners were of every race and people but their faces shared a knowing, cynical cast. ‘They can’t believe in the worm men here, can they?’ she asked Lahiru.

‘And why not? Haven’t you ever wondered why the shipforts always circle their lakes and the wagons of the landborn move once a week?’

‘That’s to remind us of our origins. We’re shipfolk – to move brings us luck. I learned that from my nursemaid.’

‘Maybe.’ Lahiru grinned, shaking off his unaccustomed thoughtfulness. Nethmi knew his light-heartedness irritated her uncle, but she’d always found it appealing. He’d been the same as a boy, back when her father was still alive and she’d imagined herself destined to be his wife, uniting the neighbouring shipforts in one family. But her father was dead and her uncle had chosen his own daughter Babi for Lahiru. He’d given her three children but little happiness, nor she him. And soon Nethmi was to be married to old Lord Thilak, an even less joyous union.

‘So, what shall we do now we’re here?’ she asked.

He pointed above her, to a pennant hanging from a roof beam, showing a rayed sun. ‘See that – it marks the company whose territory we’re in. Journey’s End, I think. Traders. And those others—’ he pointed over the roofs to distant regions of the fair ‘—the raven is Jaspal, so that’s the Fierce Children’s district. They’re in charge of the Menagerie, filled with animals from all over the world.’

‘I’d like to see that.’

‘I think it’s near the centre. And that–’ He blushed and froze with his hand pointing at a banner showing two dice with a strange bulbous-ended rod between them.

‘That there’s Smiler’s Mile,’ a high voice piped up and a girl no more than ten insinuated herself between them. She smiled, gap-toothed, and swung her arm in a wide circle over the roofs of the fair. ‘The fat man with a spoon, that’s the Merry Cooks. It’s them what serves the food, though I ain’t saying it’s good. The horse is the Drovers, no need to worry yourself about them – they ain’t for visitors. The snowflake’s the Snow Dancers. See, it’s simple. Queen Kaur’s face, that’s the Queen’s Men. You don’t want to go near them. They don’t do nothing but rob.’

Lahiru smiled and ruffled the urchin’s hair, though it was filthy with grease. ‘And the winged mammoth? I confess I don’t find that one so simple.’

The girl squirmed away from his touch. ‘The King’s Men. They put on plays. Boring. But that one—’ she pointed to the simplest banner of all, the black silhouette of a figure against a white ground ‘—that’s us Worshippers. We’re the best of all the companies, because we keep company with the gods.’

‘So we should go there, I suppose?’ Nethmi said. ‘That’s your impartial advice?’

‘No,’ the girl said. ‘Winelake Square in the Fine Fellows’ quarter. That’s where Jinn’s preaching today and he’s the best of all the Worshippers. You ought to go there.’

Nethmi pulled out a glass feather, but Lahiru took the coin from her and held it out of the girl’s reach.

‘Jinn, you say? The boy preacher who teaches disrespect for the Five and sedition against our King?’

The girl shrugged, seeming more annoyed than alarmed. ‘Some people think so, but he keeps the fair’s peace and the fair keeps him safe. Why not hear him out?’

Lahiru held the coin a moment longer, then tossed it to the girl and watched her catch it, bite it, slip it somewhere beneath her cloak and melt back into the crowd.

‘Well?’ Lahiru asked, turning back to Nethmi. ‘Shall we hear sedition being preached? Your uncle would be furious if he learned of it.’

She thought of her upcoming marriage, unwanted and inevitable, and returned his sly smile. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘He would.’

Eric didn’t have many strong opinions, but he felt strongly that if a boy was about to be replaced, it was kinder not to let him know. It didn’t seem Madam Aeronwen shared the sentiment, though. Not with the way she was fawning all over Kenric while the rest of her sellcocks and dollymops gobbled their lunch in the kitchen paying customers weren’t invited to.

The room was cramped and rough, nothing like the public areas of the house. The wooden ceiling was low, the walls unpainted and the smell of stew made from tainted meat lingered. Eric liked it here, or he always had. But that had been when he was the one being smiled at and slipped little treats. Now it was Kenric.

Kenric was lapping it all up, the way he always did. He picked at pieces of fruit and put them in his mouth one at a time, being sure to lick his lips and his fingers of the juice after each. It was shameless, even for a whore of Smiler’s Fair, but Eric knew he only had himself to blame.

Six months ago, Kenric had been a stable boy with the Drovers, miserable and with many years of shovelling shit left ahead of him before he bought out his debt bond and earned full membership in the company. Eric had shared a few small beers with the thirteen-year-old, and maybe he’d boasted a little about his life in the Fine Fellows and how he was near halfway to buying out his own bond.

But he hadn’t known that Kenric would go to his master and beg him to sell his bond on to Madam Aeronwen. Nor that she’d shell out so many gold wheels for the boy, who was pretty enough to be a girl and young enough to have no hair on him and skin as smooth as a baby’s.

The lad seemed to feel Eric’s eyes on him. He grinned and rose, oozing over towards him until he was sitting in Eric’s lap with his thin arms around his neck.

‘Tell you what, mate,’ Kenric said. ‘I’m out of lotion, and you got that palm oil what your clients go crazy for. Lend me it, will you?’

‘It’s mine,’ Eric protested. ‘I paid for it.’

Kenric batted his long lashes and looked up through his curly honey-coloured hair. ‘But you ain’t using it. You ain’t got no gentlemen booked today, and I got three.’

‘Give it him, Eric,’ Aeronwen said, her square face stern. ‘I’ll drop you five glass feathers, if you’re begrudging the cost.’

And that, of course, was that. Kenric left Eric’s lap as soon as he had what he wanted and they all went back to eating. Except Eric didn’t have much of an appetite any longer. He put down his knife and stood.

‘Off to drum up some custom?’ Kenric asked in that sweetly poisonous way of his.

‘Going for some

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...