- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

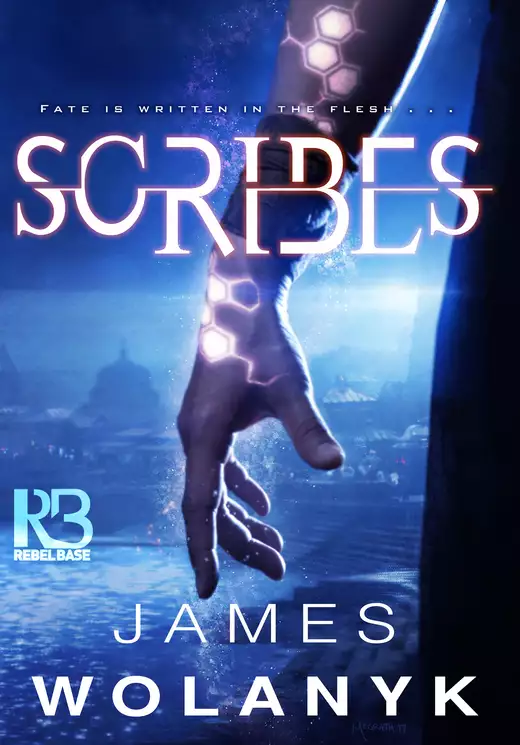

Pawns in an endless war, scribes are feared and worshipped, valued and exploited, prized and hunted. But there is only one whose powers can determine the fate of the world . . . Born into the ruins of Rzolka’s brutal civil unrest, Anna has never known peace. Here, in her remote village—a wasteland smoldering in the shadows of outlying foreign armies—being imbued with the magic of the scribes has made her future all the more uncertain. Through intricate carvings of the flesh, scribes can grant temporary invulnerability against enemies to those seeking protection. In an embattled world where child scribes are sold and traded to corrupt leaders, Anna is invaluable. Her scars never fade. The immunity she grants lasts forever. Taken to a desert metropolis, Anna is promised a life of reverence, wealth, and fame—in exchange for her gifts. She believes she is helping to restore her homeland, creating gods and kings for an immortal army—until she witnesses the hordes slaughtering without reproach, sacking cities, and threatening everything she holds dear. Now, with the help of an enigmatic assassin, Anna must reclaim the power of her scars—before she becomes the unwitting architect of an apocalyptic war.

Release date: February 20, 2018

Publisher: Rebel Base Books

Print pages: 343

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Scribes

James Wolanyk

Their baying rose from the southern bogs, low and tortured, warning fieldmen to gather roaming sows and bleary eyed mothers to bolt their shutters. Then came the screeching that told caravan drivers to seek refuge behind earthworks and palisades.

But the targets of their hunt had no time to think of shelter.

Anna, First of Tomas, was too busy thinking of death. She wondered if it would be sudden and painless, numbing her exhaustion like bathing in winter streams. Perhaps death was agonizing, which explained the sobs of feverish men who—

Just two leagues, she reminded herself, even as her steps faltered among the oaks and saplings and lichen-choked stone, all looming monstrously in the fog. Even as her pulse drummed in her temples. The lake is two leagues away. But the air was humid and foul, too thick to breathe. Everything smelled of carcasses reclaimed by the mud.

Her predictions had placed the trackers at five leagues by dawn, yet beyond the latticework of branches, the skies were still a murky wash. Darkness hadn’t yet been flushed from the horizon. No, it was impossible for them to make up this much ground before sunrise. They’d come earlier every year, ever since the village started to learn their tactics, but this was calculated.

Somebody told.

“What is it?” Julek winced. “You’re hurting me.”

Anna glanced down. She’d absently clamped onto her brother’s wrist, turning his fingers a pallid blue. Her grip eased as she focused on the predawn stillness. Mother often told her that she had their kin’s sharpest ears, but now she hated the honor. She heard the rustling of shrubs, the startled flight of a thousand birds, the slap of paws on damp reeds as huntsmen cut across the floodplains.

“Nothing,” she said, hoping the boy was too young to understand. She was hardly an elder, but old enough to tell convincing lies. Old enough to make an eight-year-old feel that he wasn’t being hunted, and that they’d spend their morning with toes dipped in crisp water, staring out at the dark pines across the lake. Weaving her fingers into the links of her silver necklace, Anna pulled Julek toward the ferns. “If we don’t hurry, we’ll spend all day out here.”

“It isn’t even sunup yet,” Julek said. He frowned at the beasts’ cries. “Anna, what’s that?”

“Elk,” she whispered.

Ahead lay the gloom of deeper woods, and behind them, a sprawl of waterlogged fields. She’d been forced to carry Julek through the bogs, and all the while she’d made him laugh by pretending she was his warhorse. Her new boots were ruined, and her linen leggings were soaked to the knee, but it hardly mattered. She wouldn’t be returning.

“Come on, little bear,” she said, waving a gnat away from her face. “Here, come on. I’ve got you.”

He scrunched his brow, clenched his tongue between crooked teeth, and swung his right boot out. Pitching forward, he caught Anna’s arm for balance. His left leg was more deformed, but the momentum pulled him into an awkward gait. “Anna, it isn’t making me fast. Whatever you rubbed on my arm.”

Anna stole a sniff of her free wrist, breathing deep for the twistroot’s sap-like odor. In its place, she smelled only sweat and ancient wool, and realized the beasts hadn’t latched onto a false scent. She’d mixed the salves incorrectly, perhaps forgetting the tallow to waterproof it on their skin. It was too late now, of course. They were closing in.

“Anna, please,” Julek whined. “I need to sit down. That’s all.”

“When we reach the lake, we can sit down. Is that fair?”

“No,” Julek said. “The lake is an hour away.”

“Less than that, if we hurry. Isn’t that right?”

“I can’t hurry.”

There was pain in his voice, and worse yet, sincerity. Back home, he could barely pace around the field or crawl onto his cot by himself, and he’d been excited by the idea of a secret trip to the lake without his riding pony. For once, he’d been trusted to keep pace on his own two feet.

Now it was an exercise in cruelty.

“Anna!”

“I know,” she said softly. She blinked away prickling tears, wondering if they came from desperation or pity. When she saw another cluster of crows scatter from the treetops, she realized it was both. “Julek, we can’t disturb these men. I need you to be quiet.”

“Why?” he whimpered. “You’re hurting me.”

Anna bit into her lower lip, threatening to draw blood. She tried to soften her grip on him, but couldn’t. Letting go meant death.

The boy jerked his arm back, twisting free of Anna’s hold.

She rounded on him with clenched fists. “Julek!”

But he was already crumpled among ferns and overhanging thistle, his breathing hard and broken between whimpers. Thorns fixed his tunic in place, leaving his legs sprawled limply behind him.

“Julek, please,” Anna whispered. She knelt beside him and reached out, but he recoiled, pinning his arm to his chest. His tunic sleeve ended above the elbow, exposing the lashes from the briar patches. Beneath the blood, mirrored across his face and neck and fragile ankles, his rounded sigil shifted in luminous white. The symbol was cryptic yet familiar in Anna’s mind: the boy’s essence, unique to him alone. To glimpse such a thing was a gift and burden known only to scribes. “I’m sorry.”

Julek glanced away, wiping his nose with the back of his hand. “Just take me home, Anna. I don’t like this. I want to go back.”

“Fine,” she said. Again she heard the trackers crashing through the underbrush. Panic put a burning flush in her cheeks. “Come on, Julek, we can go.”

The boy looked up at her, tears streaking his freckles and trailing down his dusty cheeks. “You’re lying to me.”

Branches snapped, perhaps in the grove a pence-league away.

“Never,” Anna said. She offered a hand to coax her brother’s arm out of hiding.

He shook his head. “Something’s wrong.”

“No,” she said in a broken whisper.

“You’re crying,” he said. “Anna, who are they? What’s wrong?”

Out of sight, the beasts growled.

Anna snapped her focus to the expanse of dead brush behind them, scanning for any sign of disturbance among the thorns. But the morning was still a filthy gray, staining the forest in monochrome, and she couldn’t discern anything beyond the dark slashes of trees and creeping fog. The scene only grew blurrier as her eyes watered.

She glanced back at Julek. “We’re fine. I just cut myself.” Anna held up her right hand and fought to ease the shaking. There was a smear of blood beneath her ring finger. “See? Just a small cut. I’ll bandage it at home.”

“You never cry.” His next teardrop rolled until Anna wicked it away with a trembling thumb. “Are you scared?”

No, little bear, she wanted to say, even as the teardrop stung her skin, everything is all right. She opened her mouth, but the words vanished. Cracking twigs burned away her breaths.

It all seemed so foolish now. Even if she reached the raft, she didn’t know where to go. The tanner’s son never specified which direction she had to travel to reach Lojka, nor how far. And what good were her salt clusters if she conflated pinches and grabs, and had never asked how much to pay for anything? Some of the local boys even said that the northern cities didn’t take salt as payment. Was she even going north? How far could they go without food?

The longer she stared into Julek’s eyes, the less such things mattered.

“Give me your arm,” she commanded. Julek obeyed with hesitation, and Anna took hold of his wrist with one hand and seized a wad of his tunic with the other, dragging the thin boy to his feet and bracing his body against hers. “Just like the fields, okay?” She dropped into a narrow squat and allowed him to lean forward, bearing his full weight across her back and meshing his hands beneath her chin. “I’ll keep you safe, little bear.”

On any other day, Julek would’ve been considered light. Most of his muscles were atrophied from years of housework and bed rest, and unlike the other boys—indeed, unlike Anna—his daily meal was a mug of boiled kasha. Their father could still lift him with a single arm.

But today it was all wrong.

Anna had been too nervous to eat for days. She’d traveled a league in total darkness, and another two in marshlands. Her feet were waterlogged and bleeding, her legs threatening to buckle with every step.

Lukewarm sweat beaded along her brow and stung her eyes. When she stopped listening to the wet pulse of her own heartbeats, she heard boots stomping through the brush behind her, quickening as they drew closer. With every exhale, her ribcage constricted. Stagnant air burned in her lungs as she emerged from withered grass and into the mire, hemmed in by drowning trees.

Her boots sank into the muck, squelching as she fought to move on. Flickers of memory, rusted trapper’s teeth and bloody bear flesh and desperate animal thoughts, exploded into her awareness. Escape. But every step pulled her deeper, swallowed her boots to the ankle. Julek’s weight damned them.

Anna worked to free her boot, her legs cramping with the effort, but it remained trapped. “Julek,” she said, still pulling, “if I let you down now, could you walk?”

He made no response.

She repeated the question, tugging at the boy’s trouser leg. “It’s very important.” The calm of her voice died with the crunching of nearby branches. She knew they were within sight, but she couldn’t afford to look, especially with Julek clutching her. The boy’s muffled prayers fed the dread in her gut. “Julek,” she whispered to the shuffle of unbearably close steps. “I want you to stay beside me, no matter what. I know you can do that.” Anna bent at the left knee, struggling to remain upright as Julek swung himself around and dangled freely. She reached down to pull his limp legs from the water, but the boy clutched her tighter. “Don’t worry. Just hold onto me.”

Her knees gave way, and she toppled to the left. But before she could feel the lukewarm water she collided with moss and termite-ravaged wood. Her pale arm slid into the notch between branches and exposed her own cuts, much deeper and brighter, running down leaf-littered skin from elbow to palm. But her flesh was bare, devoid of the sigils she saw on everybody else. A scribe carried no essence, they said. No protection against the bloodshed from which they spared others.

“It’s okay,” Anna whispered. Boots thumped nearby.

Julek stared up at her with wide, swollen eyes, his grip tightening around her neck. He was trying not to cry, trying to be like her. “Home, Anna. We need to go home.”

Behind her the screeching that once seemed so distant was now deafening. It was a guttural moaning, no doubt muffled in some way, communicating starvation that only trackers could put into their beasts. Flesh wasn’t enough to satisfy it now. It needed violence.

In spite of the blood, Anna’s mouth went dry. She stared at Julek as her vision blurred, and the tips of her ears turned cold. Before long the crackle of leaves overtook her ragged breaths.

“You’re quick,” said a passionless voice, no more than ten paces away. “You must be exhausted. Set him down, rest against the tree. There’s no need to hurry.”

In Anna’s mind it was a simple thing to retrieve the hunting blade tucked into her belt. But it seemed impossible to move her hands. When the beast growled behind her, close enough to rustle her trouser leggings with its hot breath, she lost her nerve.

“He won’t bite,” the tracker said. “Unless I take off his muzzle.”

Anna shut her eyes, trying to ignore the beast’s odor of spoiled lamb and urine. “You’re making a mistake.”

“Oh?” Yet the word held no curiosity.

Closer still, Julek’s fragile pleas were wasted. “I want mum. Anna, bring her here. Please, Anna . . .”

She could hardly swallow. “I don’t know who sent you, but—”

“If you didn’t know, you would be sleeping right now.”

Hearing the truth from a stranger chilled her. A week earlier, she’d heard mother and father speaking to one of the bogat’s riders, negotiating for Julek, but their involvement had seemed tangential compared to the idea of losing her brother. Her nausea swelled with the tracker’s reminder. Back at home, father would be rising soon, his rucksack laid out and ready to collect the boy’s worth in salt.

Anna squared her shoulders.

“Easy, girl.” The tracker clicked his tongue. “You don’t want to introduce violence to our meeting. My companion has more claws than you, and he’s already pulling for prey.” He let out another bit of rope, filling the silence with the groan of fibers stretching and snapping taut. Claws raked the muck and stirred the cloudy water around Anna’s ankles. “I’d hate to give him reason to feed.”

Anna clamped her jaw to stop the trembling. “I’m going to set him down. Pull it back.”

“It’s out of reach.”

But the breaths were impossibly close.

“Keep it where it is,” Anna said. Reluctantly, she took hold of Julek’s wrists and pried open his grip. After an initial wince the boy resigned, and Anna lowered him to the mud below, their hands joined in a trembling embrace. “Don’t worry, little bear,” she whispered, too softly to reach Julek’s ears.

Creaking metal filled the air.

“Do you hear that?” asked the tracker. “Hazani iron. Strung with hemp, the cartel said. So far, hasn’t missed a thing.” There was a rustling of leather, then a delicate swish. “Right. You can turn around, girl.”

Anna released Julek’s hands, their combined sweat turning clammy on her palms, then glanced over her shoulder. Unable to see around the mossy bark of the oak tree, she wrenched her boot free and rotated her entire body.

Two paces away, the soglav strained against its handler’s woven rope. When their gazes met, the creature went wild, surging forward and thrashing with gangly limbs. A rusted iron collar was the only thing separating the beast from its kill. Veins bulged beneath the shaved gray fur of its neck, and blood trickled from infected rings that spoke of razors within the collar. A leather muzzle, lashed to the broken stumps of its horns, enclosed its snout and teeth. Its eyes, black and beady and scarred by a practiced whip, widened with each tug against the handler’s rope.

But that wasn’t enough to protect her. Its claws tore at the muck and empty air in front of Anna, willing to trade agony for a meal.

Anna realized she wasn’t breathing, and only then did she detect the stench of pus. She’d never been one to scream when frightened, but now, as with childhood coyote encounters, she surrendered to fear and froze.

Half-submerged in the bog, Julek held fast to her right leg and kept his eyes shut. He clutched tighter with each snap of the soglav.

Anna covered her brother’s eyes. “Pull it back!” She could barely raise her voice above the snarling. Glancing beyond the beast, if only to calm herself, she saw the tracker waiting. “Please!”

Shrugging, the man yanked at the rope.

The beast sprawled backward and collapsed into muddy water, its arms and legs kicking as it struggled to stand. Its opportunity for a kill had evaporated, it seemed, as the soglav barely managed to lift its snout from the water and rise on its haunches. Its breathing was ragged, its muscles wobbling. Gnats swarmed over bloody flesh as they sensed the creature’s surrender.

“Stay.” His voice was cold. Though standing just ten paces from the soglav with the rope tethered to his belt, he showed no fear of the beast. He was likely an experienced tracker, and on the bogat’s payroll. He wore a linked mail hauberk, the thick gloves of a falcon handler, and a simple iron helmet, outfitted for swamp crossing with a neck guard and burlap veil. Like his beast’s eyes, his were his only window of expression. But he was neither starved nor enraged. He had the weary, drooping eyes of a dusk petal addict. And in his arms, aimed at Anna, was a crossbow with a black bolt. “He’s the worst of the bunch, Grove knows. He ate three days ago. There’s a difference between hunger and starvation.” Holding his aim, the man wandered through the muck and kicked the soglav’s underbelly. When the creature screeched and collapsed with a shudder, the tracker showed no distress.

“I’ll pay you whatever he’s worth,” Anna said, with as much confidence as she could muster. She couldn’t tear her gaze from the loaded bolt, or the fully wound hemp string that held it back. “I’ll pay double.”

“How old are you?” asked the tracker.

She narrowed her eyes. “I’m not a child.”

“Right, then. Do you understand how payment works?”

“Of course,” she whispered.

The tracker’s gloved finger slid along the crossbow trigger as though stroking the feathers of a delicate bird. “So you know that not all men work for salt.”

It crossed Anna’s mind that the tracker might not have been Rzolkan at all. Sometimes, the northern traders—those from Hazan, mostly—carried bricks of metal or packed spices. Maybe that was his currency, she reasoned. Nobody in her village had ever paid with currency beyond salt or bartering, unless a saltless trader had been forced to pay his way through with a brick of other materials. Even then, the odd bricks were always sold to another caravan for salt. But this man’s skin was too pale to be Hazani, and he spoke with the flawless tongue of someone from the eastern marshes.

Anna hardened her stare to hide her ignorance. “What do you want?”

“My cut.” He gestured at Julek with the crossbow. “Tell me . . . what did you intend to pay with?”

She recalled the ribbon-wrapped bag of salt at her hip, which now felt heavy with the weight of its uselessness. “I’ll pay whatever it takes. Please, keep this between us. You won’t have to split your earnings with the others. I’ll pay you everything.”

“It was salt, wasn’t it?”

Anna gripped Julek tighter.

“You couldn’t buy a droba with all the salt in your stores, girl.” He gave an amused growl. “And whatever you have in those little bags is worth far less than a rune. But your brother, according to my earnings in the contract—”

“I’ll get you runes.” She realized, in the ensuing silence, that she’d used her last maneuver. Her father had told her to stay mum about her gifts, to feign ignorance on the mere nature of inscribing, but now her father had forced her hand. The tracker’s lack of retort gave her a hopeful flush, and she nodded, brimming with assurances before the man could refuse. “That’s right. I can get you a rune. That’s more than the bogat could offer, isn’t it?”

The tracker’s weary eyes shifted in thought. Violet wisps crawled over his irises, indicating the petal’s haze. “It never looks good to break a contract,” he said after a moment. “They marked the boy, not you.”

Anna scowled. “His name is Julek.”

“I don’t care for names.”

“It would be outside of your contract,” Anna said with a dry throat. “I’ll pay you, and you can tell them you never saw us. We wouldn’t come back, and won’t ever cause any trouble for you. I swear it.”

“Your name isn’t on the contract, Anna, First of Tomas.” He made her name feel obscene. “I’ve no intention of dragging you before the court’s scribes for this farce.”

“We wouldn’t need to use the courts,” Anna said.

He cocked his head. “You know scribes, girl?”

“One or two.”

“Playing coy,” the tracker said. “It’s only a matter of time until they’re marked, anyway.”

It was no achievement, in truth. According to Piter, the baker’s son, there had only been two scribes born in the region since his family moved here, and that was ten years ago. And Anna knew firsthand the difficulty of hiding such gifts.

She knew the pain of it.

“It doesn’t matter,” Anna said. “I could get you a rune, some salt, and they would never know.”

“It isn’t enough.”

“A droba, then.” She hesitated to even say it, but if slavery was her only option, she would take it. There was always a way out, she’d found. Given enough time, she could escape. And even if he forced her to bed, she could—

“Do you think the bogat is a fool?” Another huff stirred his burlap veil, this one bearing a trace of indifference. The sort of indifference that only eunuchs or man lovers or people incapable of love could ever muster. “No need to answer, girl; everybody knows he is. But he loves his runes, and by the Grove is he a jealous lover. It would be remarkable if I reappeared in his court with a rune, and a sweet young droba, yet no sign of dear Julek, don’t you think?”

Until that moment, Anna had never understood what elders meant when they spoke about hopelessness. In previous years, her father’s smile had made the world feel less hateful.

Now her father was part of that hateful world, and she had only herself. With Julek’s every squeeze on her leg she felt the tiny iron teeth of her father’s traps. The silver necklace father had given her so long ago threatened to choke her. “My service would last a lifetime,” she whispered. “You’d never have to work for another bogat. You could live—”

“You’re wasting my time.” The tracker glanced sidelong, watching his broken soglav’s ears flutter at the sound of distant movement. “They’ll be here soon enough, girl. So I suggest you sweeten your offer.”

The other trackers’ graceless footfalls rang out, halting Anna. It was too gloomy for her to see the men or they her, but she knew the sun would appear soon. When it did, not even this tracker’s silence could protect them. Her throat closed, and her fingers went numb.

Julek’s small hands clasped around hers.

She inhaled. “I’ll give you all of my salt, my oath, a rune, and—please. I know I have more salt near the fields. I hid it under a stump last autumn.”

The tracker remained silent, letting the snap of branches fill the air. “That’s not enough for retirement,” he said finally. “I would need—”

“A scribe.” Her eyes throbbed as she tried to hold back tears. Before the man could reply her composure shattered. “I could get you a personal scribe.”

The crossbow shifted away from Anna, but the movement was so slight that it appeared accidental. “A scribe, for him?”

Anna nodded, shifting her hands to mingle her fingers with Julek.

“How would I get them?” His voice seemed more earnest than toying now, and that meant it was Anna’s chance.

“I’m the scribe,” she said, stunned by how foreign the phrase felt. It was true, but somehow it felt wrong, as if it were a dream or a ruse. They were words she’d been told to repress. But it was her mother and father who’d promised her security for her secrecy, and now their word meant nothing. She wanted to repeat the words out of spite. Those words tingled on her lips. I’m the scribe, and I hate you.

But the tracker’s eyes remained inert. “Is that so?”

Anna nodded.

The tracker stepped closer, crossbow at the ready. The mist thinned between them, revealing a pale neck, thick and free of any runes.

He would die here.

Anna’s hand broke away from Julek, creeping toward her blade. She’d never known the bogat’s best men to work without a rune on their neck, placed by a knowledgeable scribe and written for their sigils alone.

I’m a scribe, and I’m going to kill you.

“Hands,” the tracker said. He pointed with his crossbow. “Move the boy over here.”

Showing no resistance, Anna placed her hand back on Julek’s shoulder, well within the man’s line of sight. She just had to play by the tracker’s rules, and strike when the time arose.

“Julek,” she said, gently clutching the boy’s shoulder, “I want you to go and stand by this man. He won’t hurt you, okay? I’ll be right here.”

The boy met Anna’s gaze with a sniffle. He kept her gaze for a full moment, perhaps waiting for her to reconsider, then gave a nod.

“That’s it,” the tracker cooed. He glanced at the soglav, whose ears had stilled as the hunting party changed course and grew more distant. “I don’t want this to be any more tedious than it is, so we’re going to talk with some insurance. Fair, eh?”

Helping Julek to his feet, Anna frowned. “Yes.” She pulled her brother close to her again, keeping her hands around his neck to avoid suspicion. It wouldn’t be difficult to draw her blade when the time came, but crossing the distance between them, especially with a loaded crossbow, would be the real challenge. And the method to kill the man was not immediately clear either. He was covered in riveted mail, and surely much stronger than her. “What will you do with him?”

“Keep him out of our dealings,” the tracker said. He whistled, and the soglav’s ears perked up. Its eyes opened on the second call. “Send him over there, would you?”

She peered into Julek’s eyes, trying to assure him with an even stare. She clenched both his shoulders this time, and guiding him backward, gestured for him to turn. Letting go of the boy’s tunic churned the bile in her gut. Soon enough they’d be home free, and the kupyek would be dead at her feet. As Julek hobbled toward the soglav, Anna wondered how it would feel to take her first life.

Soldiers did it all the time. It couldn’t be too difficult.

“You say you’re a scribe,” the tracker said as he traced Julek’s walk with the crossbow. He clicked his tongue and the soglav dragged itself up from the muck, straining against its rope to sniff at Julek. Despite his veil, the tracker’s amusement leaked out through hungry eyes, relishing the way Julek squirmed.

Anna forced herself to look at the tracker. “I am,” she said. “If I go with you, you’ll let him go.”

“You’re negotiating the deal now?” He laughed. “I appreciate the initiative.”

“Yes or no?”

“Your story’s already pushing it, girl. But if you’re what you say you are,” the tracker snarled, “how would I even know you’d be good company? You could run away, and I’d be more the fool because of it.”

Anna frowned at him. “I have no reason to deceive you.” She scanned the weaving on the tracker’s burlap sack to determine if his jugular was prominent. It was. “You know where I live. You know where my family lives. If I slight you, you can go there.”

“Same home you’re fleeing, isn’t it?”

The soglav’s jaws snapped behind its muzzle. Anna shut her eyes, desperate to block out the spectacle. “Anybody in my village knows my face.”

“Would they give you up?”

Anna opened her eyes. “For a bag of salt. But if you’re out here, you need much more than that. You need a rune, at least.”

The tracker’s eyes wavered out of acknowledgment. Surely he knew about his own vulnerability; desperate men did desperate things. “What gave it away?”

“Your neck,” Anna said. “Always the neck.” Runes had been placed on other areas, according to the tales, but they existed for a fraction of the throat marking’s lifespan. It made it easy enough to see the marked ones, if nothing else.

“It’s too damned hot for a neck sleeve.”

“You asked me how I knew.”

The tracker huffed, but this time it was a cold, mocking sound. “The bogat will make your mother into a plaything for his warriors,” he said. “The only thing he hates more than unlicensed runes is an unlicensed scribe.”

Anna’s face was stone. She’d been expected to crumble under the man’s threat, but it was no use. Her parents deserved whatever fate they received. They had gotten her into this trap, and only she could get them out. “Do we have a deal?”

“You’re persistent.” His crossbow’s trajectory never strayed from her stomach. “And clever, I’ll admit. So let’s say we have a deal for the time being. You’ll give me a rune as a show of good faith, and we’ll be off. Without him.”

Anna spared a glance at Julek. She was prepared to see the tracker’s blood spurting as if from a beheaded chicken, but she couldn’t bear her brother’s pain.

“And don’t proceed with your ideas of murder,” the tracker said. “There’s a reason I take precautions.”

Another hot wave of panic touched her cheeks. She realized that they both had collateral on the table. Even if her blade severed his jugular during the rune-scarring, the soglav would make a bloody mess of Julek. And there was no telling if the boy’s screams would alert the others.

“Bleeding virgins, this is heavy,” the tracker mumbled. He set his crossbow against a tree without releasing the tension. Even as he took hold of the soglav’s tether on his belt, he stared at the weapon longingly. “Well made, but dense. I’ll have to have it hollowed out.” He spoke as though Anna had asked him about the device. Then he glanced up and flexed a gloved index finger, beckoning Anna forward. “Don’t be shy.”

She waded out of the muck, blade clenched in her right hand, her steps slow and deliberate. She handled the weapon as though it possessed her, keeping its edge well within the tracker’s sight. Only in the shadow of his linked mail and rotting burlap did she understand his true size.

He had the jaundiced eyes of a man craving excess, and the smell of one too. Like the caravan workers, he gave off the odor of fermenting barley.

“Right here.” The tracker lifted the tatt

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...