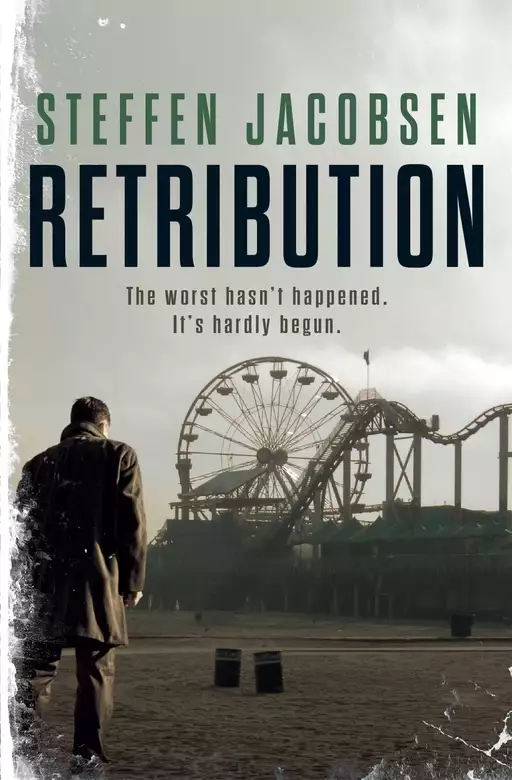

Retribution

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“[An] electrifying tale of personal morality pitted against ruthless inhumanity . . . Stieg Larsson fans will find much to like" ( Publishers Weekly, starred review). On a warm Autumn afternoon, Denmark's largest amusement park, Tivoli Gardens, is devastated by a terrorist attack that leaves more than 1,200 dead. No one claims responsibility for the attack, and seven months later the nation is still reeling and the police have no leads. Police Lieutenant Lene Jensen has been assigned to the frustrating case from the beginning. When she receives a desperate phone call from a Muslim woman who later turns up dead, she sees a connection to the Tivoli bombing. Lene's initial investigation suggests that the woman was unknowingly part of a secret research project conducted by the government, and as she digs deeper, she is met with increasing resistance from her superiors. Together with private detective Michael Sander, she tries to get to the bottom of the complicated case—only to realize that someone knows a lot more than they are letting on. With the threat of another attack looming, Sander and Jensen must race against the clock to save lives and restore peace of mind to the people of the idyllic country.

Release date: July 3, 2018

Publisher: Arcade

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Retribution

Steffen Jacobsen

The shattered body of the martyr smells of musk.

Hamas commander, Gaza

Contents

Prologue

PART I

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

PART II

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

PART III

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

Epilogue

Prologue

17th September

The year of Makkah 1434

Nabil had seen his mother so clearly, sitting among them in the stranger’s living room. He had asked for her forgiveness for what he was about to do, but she had cried out that he must think of mankind’s capacity for mercy. Enough people had died.

His resolve had wavered under the pressure of his mother’s pleas until Fadr shook him awake.

‘Who are you talking to?’ he demanded to know.

His friend had grown a sparse moustache to hide his cleft palate, which had never been properly fixed.

‘No one,’ Nabil said.

His mother was a mirage who existed only in his mind. He had barely eaten these last few weeks and they had told him that hallucinations were to be expected.

After a mortar attack that had destroyed half his childhood street in Damascus, he had dug out the bodies of his parents and his sisters, Basimah and Farhah, from under the rubble in the family’s courtyard garden. Together with Sufyan, the imam, he had washed and swaddled them and said salat al-janazah, the funeral prayer, over them.

From that day Nabil had been with the militia. While tens of thousands of his countrymen were killed and millions made homeless, the EU, NATO and the USA kept behind their own red lines, vetoed to death by the UN’s Security Council. Oil, natural gas, trainers and Putin’s ego were more important than Syrian lives, and Nabil hated them all.

With his twenty-four years, Samir was the oldest of the three men in the flat on Nørrebro. He left the lookout post by the window, kneeled in the early morning light between Nabil and Fadr and turned his palms towards the sky.

‘Nabil, cleanse your soul of unclean things. Forget all about what we call the world and this life; the time between you and your marriage in heaven is now very short,’ he said.

‘Subhan’ Allah, God’s honour,’ Nabil and Fadr mumbled in unison.

Fadr placed something in Nabil’s hands. He unfolded the black scarf with golden characters. Drops of sweat fell from his close-cropped hair and left tiny marks on the fabric.

‘Al-uqab, the Eagle,’ Fadr said solemnly. ‘The flag of Saladin. Mohamed al-Amir Atta carried it with him to the towers in New York.’

‘I will carry it with honour, insha’ Allah, if God be willing.’

Nabil folded the scarf.

‘I should go and wash,’ he said.

The bathroom was filled with feminine scents. In order to respect the home and hospitality of their unknown host, they had not opened a single cupboard or pulled out a single drawer in the flat. There was little by way of decoration in the living room: a map of the world and a poster of a black cat drinking absinthe from a tall glass. The only evidence to suggest that the owner belonged to the network was the Koran on the bedside table, bound in red leather, which, after having been touched by many hands, had eventually become as soft as kid gloves.

Food had been set out for them when they arrived and the only one who had left the flat was Fadr, who had gone to buy more cigarettes from the kiosk across the street.

Nabil washed his face and dried it with a towel that also smelled of the owner of the flat, turned off the light, opened the window to the courtyard and looked up at the sky above the rooftop opposite.

‘Aldebaran, Alnath, Alhena,’ he mumbled.

He had looked at the same stars from the deck of the ship as she sailed up through the Øresund between Denmark and Sweden, to bring them to this small country. When she had dropped her anchor, Samir had paid off the captain with a fat bundle of euros. Then they climbed over the bulwarks and down into the dark-grey rubber dinghy waiting for them on the calm, black water. Samir and Fadr had paddled the dinghy towards the shore, guided by flashes from a torch, while Nabil sat in the stern with the suitcase containing explosives and detonators between his knees. They had let the waves carry the rubber dinghy up onto the beach, then they had pushed it back into the water and walked across the wet sand until they were met by a figure that had stepped out from between the trees.

Samir had exchanged a few words with the stranger. There might have been a brief embrace before they walked, single file, up a steep slope. The figure had moved softly and surefootedly and Nabil had concluded that it must be a woman. They were taken to a white van in a deserted car park. Samir took the front passenger seat, while the other two sat on the floor in the back with their suitcases and rucksacks.

He heard a mobile ring in the living room. When he came out from the bathroom, Fadr and Samir looked very solemn. Fadr put the mobile in his pocket and Nabil’s knees nearly buckled beneath him.

‘Be strong, shaheed,’ Samir said as if he could understand what Nabil was feeling. ‘Do not say of those killed in the name of Allah that they are dead. No, they live like shadows among us, but we do not see them.’

The mobile vibrated in Fadr’s pocket and he read the new text.

‘The car is downstairs.’

*

It was cold and the three of them sat close together in the back, swaying in unison every time the van turned a corner.

Samir found a Thermos flask, unscrewed the top and sniffed the contents before passing it on.

‘Tea?’

Nabil nodded. In the grey light of dawn he studied the white, star-shaped scar on Samir’s temple, half hidden by his friend’s long black hair. The Syrian would touch it from time to time when he was agitated or deep in thought. He had never explained how he got it. A ‘miracle’ was all he would say. It looked like a gunshot wound, but how could anyone survive a gunshot to the temple?

The young men had met each other three months ago at a training camp in Iran, and Fadr and Samir had become the closest Nabil had to a family. It was the custom that a believer walking the path of the martyr, as-shaheed, recorded a message or read aloud a statement to a video camera. Later, the family could show the recording to friends and neighbours and post it on the Internet. But although this mission constituted a mighty attack on this warmongering and blasphemous small country, his family was with him right now and so Nabil had nothing to say to a camera.

He was not surprised that he had been chosen. Since his childhood, it had been both natural and necessary for him to turn to God. Sufyan, the imam who had taken him in when the civil war broke out, had recommended him to mufti Ebrahim Safar Khan and the network, and sworn to his piety and suitability.

Finally the van came to a stop; the driver pulled the handbrake on and turned the engine off. The door on the driver’s side opened and shut with a bang. They heard light footsteps that faded away – then nothing.

During the next few hours they dozed while the world outside grew lighter. They could hear voices in many languages, hurried footsteps, children, bicycles, car and bus engines, crashing gear changes and squealing tyres.

The tea had failed to take away the dryness in Nabil’s throat. One moment he would freeze, the next shiver feverishly. Groggily, he watched the second hand on the watch on Fadr’s tanned wrist, which quickly, far too quickly, completed its journey around the clock face.

At ten thirty exactly, the other two sat up and Nabil buried his face in his hands. He sat for a few seconds with his gaze aimed at the floor of the van before he squatted on his haunches and held out his arms.

The suicide vest was as heavy as the sins of mankind. Four rows of slim, rectangular blocks of Semtex had been stitched into canvas pockets on the front and back. The heaviest parts were the flat plastic bags with ball bearings taped around the blocks: tens of thousands of steel bullets would leave Nabil’s body in a spherical cloud of death when he detonated the vest. There were additional explosives in his shoulder bag.

Samir attached the vest around his waist with sturdy straps, steel wires and padlocks, so that no heroic ticket inspector or police officer who found him suspicious would be able to remove it without setting it off. Meanwhile Fadr checked the detonators, the batteries and the wires on his back.

Then Samir helped him put on a loose-fitting, light-coloured anorak and zipped it up to his neck. With shaking hands, Nabil placed a blue baseball cap on his head. He had closely cropped hair and no beard; he wore a pair of orange Nike trainers and a pair of faded Levi’s jeans. He looked like thousands of other young men in Copenhagen.

They embraced each other.

‘Assalamu alaikum,’ Samir and Fadr said, both speaking at once.

‘Walaikum assalam,’ Nabil returned the centuries-old greeting.

‘I’m proud, and I envy you,’ Samir said. ‘Next time, God be willing, it’ll be me or Fadr who will plunge the sword into the belly of Denmark, or another crusader country that murders our people.’

‘Insha’ Allah,’ Nabil mumbled.

‘Do you have the map of the park?’ Fadr asked.

Nabil nodded and patted the inside pocket of his anorak, but he would not need a map. Anyone could identify the target simply by craning their neck.

Nabil got out and turned to the other two.

‘The woman will let me in?’ he asked.

Samir nodded.

‘Ma’assalam, fi aman Allah, go with God,’ he said. ‘The woman will be there. And we’ll be there. You’re not alone.’

Nabil straightened up and started walking at a fast pace, keeping his eyes on the pavement. It was easy now. Soon it would be over. He felt as if he were observing himself from above, moving diagonally across a wide street with heavy traffic, walking towards the eastern end of the amusement park.

He wiped his forehead with the sleeve of his anorak and pressed the brim of his baseball cap further down over his eyes as he approached a small, barred entrance gate. The sun was high in the sky; it was very hot and bright, but the shade provided by the trees was deep and cool. Nabil saw a woman’s figure behind the fence and heard a click from the lock. He slipped inside and found himself in a narrow passage between a restaurant and an amusement arcade, out of sight of the surveillance cameras in the park. The smell of food coming from the restaurant and the flies buzzing around the waste containers made him feel hollow and nauseous. But the scent of the woman was fresh. He guessed her to be the same age as him. She was wearing a white, short-sleeved shirt, black trousers and had a long white apron tied around her slim waist. The name of the restaurant was embroidered in green above her left breast. She wore no jewellery and her hair was uncovered. It was put up in a bun at the back and held together with two crossed, yellow pencils. Nabil felt vaguely ashamed on her behalf, but understood why it had to be this way: whether or not she belonged to the network, she had done what she was supposed to do. Opened the door to Paradise for him.

He wondered if she was the same woman who had picked them up on the coast, if they had stayed in her flat these last few days, if she had driven them to the target. Did she know Samir? He felt a stab of jealousy, but suppressed the emotion immediately. Jealousy belonged to this world.

‘My name is Ain,’ she said in Arabic.

Nabil nodded but made no reply, and she promptly took his wrist and fixed a paper strip around it. He was too taken aback to resist her cool fingers. He could not remember the last time he had felt a woman’s touch.

‘This is a multi-ride ticket,’ she said. ‘You can go on all the rides in the park without paying. All you have to do is show them this wristband.’

‘Rides?’

She smiled.

‘Yes, they’re fantastic. This is a great place.’

‘Will you be staying here in the restaurant?’ he asked her gravely. ‘I mean, right here? Working?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then stay in the restaurant, do you hear me? Don’t go anywhere.’

‘I promise,’ she said, seeking out his eyes under the baseball cap. ‘Why is that so important?’

‘It’s important to do your job well,’ he said, as if he were much older and wiser than her.

She brushed a strand of hair behind her ear and adjusted the bun at the back of her head. Her breasts strained against her white shirt and Nabil stared at the ground.

‘Very well, very important, then I had better get back,’ she said with a smile. ‘By the way, are you cold?’

‘Eh?’

‘Why don’t you take off your jacket?’

‘I’ve come straight from a desert. I think your country is very cold.’

He shivered as if he really did feel cold.

‘Which desert?’

‘Just a desert, all right? Sand, snakes and dust. Sun.’

‘Okay. When you get hungry just come back and knock on that door over there. I’ll give you some food. You won’t have to pay.’

He looked past her.

‘I will, little sister. Walaikum assalam, Ain,’ he said, but there was something in his voice and posture, something he could not control, which made her smile freeze on her lips. Then she turned and went back inside the restaurant.

Nabil sighed. His nostrils expanded. That scent again. It was fleeting and intangible, but he was convinced that he recognized it from the flat. He walked towards the door to the restaurant and opened it. Between steel tables chefs dressed in white were busy with steaming pots and dishes piled high with meat, fruit and bread, but no one appeared to take any notice of him.

Ain was putting glasses on a tray, but turned when he called out. Again her hand tugged the hair behind her ear and she came towards him, walking between the tables.

Nabil stuck his hand into his heavy shoulder bag and found the scarf with the holy characters. He stepped backwards out into the alleyway as she held the door open for him.

‘Ain . . .’

‘Yes? By the way, what’s your name? You must have a name?’

‘Nothing. My name is nothing. Nabil, perhaps.’

He pressed the folded scarf into her hand.

‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Thank you so much.’

‘What for?’

He pointed to the band around his wrist.

‘The rides.’

She made to unfold the fabric, but he clasped her cool hands.

‘Wait,’ he said. ‘And promise me you’ll stay in the restaurant?’

‘I will, but—’

‘Goodbye.’

*

Nabil was carried off by the slow stream of people moving through the park. They had told him that everyone who visited Copenhagen in the summer would come here.

He walked north-east. Don’t look people in the eye, don’t look at their faces, they had told him. They are nothing. They are shadows walking in the valley of death, but they do not know it. They are kufr, infidels. Non-humans, Nabil.

The air was heavy with the saccharine scent of sweet shops, candyfloss stands and ice cream parlours. He could almost feel the sugary crunch between his teeth and looked with contempt at the spoiled, fat people around him.

He stayed at the edge of the crowd and could see that in three hundred paces he would be standing right under the target: the eighty-metre-tall steel construction which had the peculiarly apt name the Star Flyer, northern Europe’s highest carousel.

There was room for twenty-four people on the carousel. Passengers were carried skywards by strong, pneumatic pumps and whirled around for a couple of minutes in seats attached to long chains.

Nabil wondered if some of the bodies would end up in the streets outside the amusement park. The Pakistani engineer who had shown them the construction blueprints, the technical photographs and a model of the Star Flyer, had identified the steel mesh tower’s northern plinth as the target. When this section of the carousel’s tower collapsed, the concert hall, several restaurants and amusement arcades would lie right in the line of its fall.

He waited outside the railings until a group of visitors had left the steps leading down from the tower and a new group had taken their seats. The pumps squealed and the large platform started to rise. Nabil glanced at a young, blonde woman in a glass cubicle, who was operating the pumps. She kept her eyes on the platform while her hands were busy moving the levers. He straddled the low fence, pushed a couple of children aside and scaled another set of railings.

Someone tried to restrain him, but he wriggled free and ran underneath the construction. He pressed his cheek against the cold steel of the girder, embraced it as he listened to the squealing people high above him as the Star Flyer at the top of its tower flung them through the blue skies above Copenhagen. The steel vibrated against his cheek.

He saw two ticket inspectors come running towards him, saw them comically retreat when he unzipped his anorak and they spotted the vest, the yellow wires and the blocks of explosives.

Then he smiled at the blonde girl behind the glass. She had a walkie-talkie pressed to her ear. He thought about his mother, his sisters – and the girl, Ain. He hoped that she had stayed inside the restaurant.

Nabil grabbed the detonator in the pocket of his anorak, closed his eyes to the sight of human faces and his ears to their screaming.

‘Allahu’ Akbar, God is great,’ he whispered as he pressed the button.

1

The lecture theatre at Copenhagen Police Headquarters was packed to the rafters. People were sitting on the floor, along the walls and around the desk housing the technician, his projectors and computers.

It was one of the few advantages of being a superintendent, thought Lene Jensen, who was sitting in the middle of a row of chairs. She was certain to get a seat, even though she had recently crashed down spectacularly through the ranks.

She was with colleagues from Rigspolitiet (Denmark’s national police force), the Danish Emergency Management Agency, various government departments, PET (the Danish Security and Intelligence Service) and FET (the Danish Military Intelligence Service). The ranks and salary levels that mattered sat in the front row.

The American on the podium was the most recent terror expert to be invited to Copenhagen to explain to the authorities what had happened that September day in the Tivoli Gardens last year – from a retrospective and informed perspective.

He was tanned, tall and sinewy and had the shoulders of an officer. He was dressed in a neat navy-blue suit with sharp creases, shiny black shoes, a white shirt and a discreet grey-striped tie, but looked as if he would have been more comfortable in uniform.

The microphone howled and the American held it further away from his lips.

‘What you have to understand is that no one in the Middle East can – or wants to – break the cycle now. Violence is inevitably paid back with more violence, creating more orphans with a deep hatred of the West and Israel. Let’s take, for example, the massacres in the Palestinian refugee camps Sabra and Shatila in Beirut in 1982. The night of the 16th September, Christian Phalangists and units from the Lebanese army moved into the camps and started massacring women, children and old people. They carried on doing so without interruption, for two days.’

Behind him old press photographs showed piles of mangled bodies of children, brickwork shot to pieces, burning tents and corrugated iron huts. The earth between the huts was red, as were the puddles in the tyre tracks.

‘After the invasion of Lebanon, the Israeli army was officially entrusted with maintaining security at the camps, but they did nothing to protect the refugees. On the contrary, they fired flares above the camps so that the attackers could work at night, and no one – no one – escaped.’

The face of the American was devoid of expression. He sipped some water before he carried on.

‘Everybody knew that Yasser Arafat had been evacuated to Tunisia a month earlier with his young PLO fighters and some of the children, and that there were no armed “terrorists” left in Sabra and Shatila. There were no angry young men with Kalashnikovs in the camps, but that counted for nothing: the purpose of the massacres was to send a message to Yasser Arafat from Elie Hobeika, the intelligence chief of the Lebanese army, and from Ariel Sharon, Israel’s defence Minister.’

The American let his gaze glide across the front rows as photographs of Sharon and Hobeika appeared on the screen.

‘Between the 16th and 18th September, the Phalangists killed approximately three thousand five hundred people. Roughly the same number as were killed during the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon in 2001. You will obviously note the coincidence between the date of the Tivoli bomb last year and the dates of these massacres.’

Obviously, Lene thought. The question was whether it was significant or just coincidental. No one had yet claimed responsibility for the Tivoli bomb, which was unusual. Although everyone had expected that every organization from Al-Qaeda to Ansar al-Islam would have claimed victory, no one had sent a letter or video to the international press agencies and no footage had been uploaded to YouTube from the tribal territories in north-west Pakistan or the Yemen.

The screen turned grey.

‘After Sabra and Shatila, the American Embassy in Beirut was attacked and sixty-three young people died. Later, the US Marines’ barracks were bombed and another two hundred and forty-one young Americans lost their lives. The Middle East is a chronic, political epicentre. An animal that eats its young and that of others. Someone has to break that cycle, ladies and gentlemen, or history will judge all of us harshly. Any questions?’

A muscular man to Lene’s far left got up, raised his hand and was handed a microphone. Lene did not recognize him, but he looked like your typical intelligence agent: early forties, fit, wearing jeans and a black T-shirt. His sleeves were pushed up over impressive biceps but his lean face was burdened, his eyes raw and sunken, and his short dark hair prematurely greying. A vein throbbed slowly in his neck.

‘Deputy Chief Superintendent Kim Thomsen, PET,’ he said. ‘If we, or anyone else, are to break the cycle, surely we have to put the attack into a meaningful context, no matter how twisted that context is. That’s quite difficult when no one has claimed responsibility.’

The PET agent’s body language was perfectly controlled, but a certain fatigue in his voice suggested that he had been personally affected.

As had practically everyone in this tiny country, Lene thought. Everyone had known, been related to or heard of someone who had been in Tivoli on the 17th September. The bomb had dealt an almost fatal blow to a country that history had otherwise treated so gently. The Danes were unprepared, they had never experienced anything like it, and they had no idea how to respond.

Her mobile vibrated against her thigh. She shifted in her chair and ignored it. Her eyelids were leaden. She could not remember when she had last slept without the help of sleeping pills, red wine or vodka – or a combination of all three.

The American nodded.

‘I don’t think anyone familiar with the Middle Eastern scene today would not place responsibility for the Tivoli attack with a jihadist terror cell. The fact that no one has claimed responsibility for this act of terror is in itself a kind of signature. Al-Saleem from Tehran and Sheikh Ebrahim Safar Khan from . . . God knows where . . . but probably Amman, have made it their trademark never to claim official responsibility for their actions. Both of them head small but well-organized units of dedicated young men and women.’

The PET agent with the microphone did not appear to have any comments to make, so the American continued.

‘These terrorists are highly educated, but more than that, they are patient. They are fighting for a global caliphate and view the extermination or the conversion of all infidels as a necessity. But they are also men and, perhaps even more so, women who to some extent live in the Middle Ages, while we, the Western intelligence services and police forces with all our satellites, drones, listening stations and computers, are from the future.’

He gestured towards the audience.

‘To them, you’re all science-fiction creatures. We live in two parallel but separate timelines, and it’s unbelievably difficult to bridge the gap, track them down . . . and liquidate them. We in the West are incredibly vulnerable because no one can defend themselves against a determined man or woman who doesn’t care about dying. It short-circuits our whole way of thinking because we would never choose death, and certainly not for a “cause”.’

The man who had introduced himself as Kim Thomsen looked confused, but the American smiled supportively.

‘As a rule they don’t use mobile phones, but when they do, they use prepaid burners and just say a few words or send a text message before destroying the phone. They know each other’s appearance, each other’s clans, families, dialects and accents, and they have proved their loyalty. They have all executed a bus full of Shia Muslims on their way to a market, blown up a school for girls, blinded a woman who claimed that she had been raped, or beheaded a homosexual. We can’t infiltrate them because we can’t ask our agents to disfigure or kill little girls. They don’t claim responsibility for their missions, and they no longer behave like rock stars – like Ilich Ramirez Sánchez, better known as Carlos the Jackal, did.’

The American stared into the air.

‘The ideological hardcore today might consist of young, well-educated women, which makes the threat scenario much more complicated. They don’t need specialist training just because they’re women. They’re discreet; they’re excellent liars and they’re generally far better at keeping secrets than men.’

A predictable murmur erupted among the female members of the audience and the American waited patiently for it to die down.

‘We all know it’s men who forget to log out of Facebook, leave the G-string in their pocket, who come home with lipstick on their collar, conspicuous long hairs on their jacket or who forget to delete breathless text messages from their cell phones when they have been with their mistresses. These women are motivated by personal tragedies. They may have lost husbands, brothers, sisters, children or parents or their country and inheritance, and they blame the West and Israel for their loss. They don’t wear burkas or niqabs or walk twelve paces behind a man. They smoke cigarettes, they drive cars, they drink mojitos, have premarital sex and listen to Rihanna. They are allowed to do this because it serves a higher purpose: destabilizing the West.’

The man had a point, Lene thought.

‘But why now? And why Denmark?’ the PET agent asked.

The tall American shrugged his shoulders and pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and forefinger.

‘Well . . . it’s no secret that we, your allies, have wondered about the relaxed attitude with which Denmark in the 1970s and 1980s offered political asylum and granted permanent leave to remain to the world and his wife, including active Muslim fundamentalists and demagogues. You welcomed them because you thought they were being persecuted by the Egyptian dictatorship, even though that is the risk you run when you plan to kill your own head of state. You felt sorry for them. Secondly, there are the Mohammed cartoons, which refuse to die and are resurrected whenever the mullahs want people out in the streets. And last but not least, you joined the coalition forces in Afghanistan and Iraq as our time’s version of Christian crusaders. Plus there could be any number of reasons that we don’t know yet. For example, a modern Islamist cell might have been set up here in Denmark and it’s testing its strength.’

‘So you’re saying that we only have ourselves to blame?’ the PET agent said angrily.

The American looked exasperated.

‘Of course not, and the truth is I have no solid facts on which to base a good answer,’ he replied after a pause. ‘Perhaps it was just your turn or you were too easy a target. We have to face the fact that the attack on Tivoli was particularly successful. You need to think and act differently if you want to prevent a repeat. Post-Tivoli, Denmark has been confronted with a new reality. The question is, are you prepared to intensify the surveillance of civilians, monitor their communication, arrest them without charges, apply physical pressure during interrogations, use truth serum, lie detectors or extraordinary rendition without warrants? Are you willing to turn yourself into a police state to prevent this ever happening again?’

People shifted uneasily in their chairs. Again? The possibility did not bear thinking of.

Lene saw her boss, Chief Superintendent Charlotte Falster, get up. The slim woman with the immaculate grey bob turned and stared hard at the PET agent until he sat down. Then she marched up to the podium, smiled and thanked the American. They were facing the audience and someone photographed their handshake. Charlotte Falster was a master of detail.

Lene’s eyelids began to close again, but when her superior’s next words struck a chord, she forced them open.

Charlotte was in the process

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...