- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

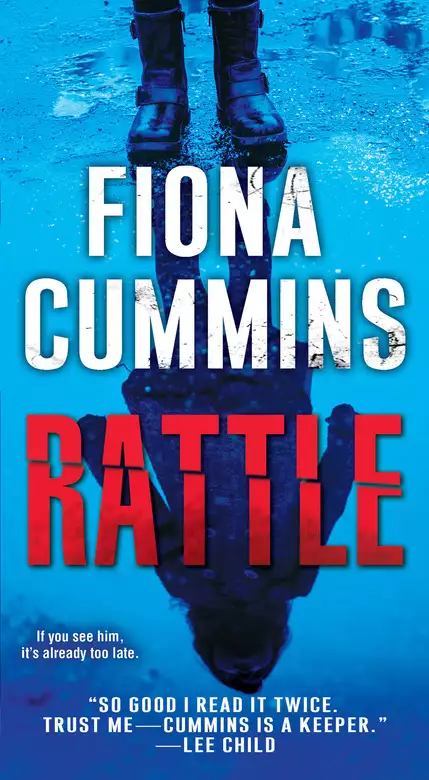

A serial killer to chill your bones.

A gripping and heart-pounding thriller that gives a glimpse into the mind of a psychopath even more terrifying than Hannibal Lecter. If you like Mo Hayder and Thomas Harris’s Silence of the Lambs, you’ll love Rattle and The Collector.

A SERIAL KILLER TO CHILL YOUR BONES. A FAMILY TO WARM YOUR HEART. A DETECTIVE WHO MUST HUNT HIM DOWN.

He has planned well. He leads two lives. In one, he’s just like anyone else. But in the other he’s the caretaker of his family’s macabre museum.

Now the time has come to add to his collection. He is ready to feed his obsession, and he is on the hunt.

Jakey Frith and Clara Foyle have something in common. They have what he needs.

What begins is a terrifying cat and mouse game between the sinister collector, Jakey’s father and DS Etta Fitzroy, a detective investigating a spate of abductions.

‘It’s a rare debut that has this much polish. Harrowing and horrifying, head and shoulders above most of the competition’ - Val McDermid

Release date: February 27, 2018

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rattle

Fiona Cummins

If Erdman Frith had chosen pizza instead of roast beef, his son might have been spared.

If Jakey Frith had been a little more ordinary, the bogeyman that stalked the shadows of his life would have been nothing more than a childhood memory, to be dusted off and laughed at on family occasions.

If Clara Foyle’s parents had been a little less self-absorbed and a little more focused on their five-year-old daughter, her disappearance might never have happened at all.

As for Detective Sergeant Etta Fitzroy, if she hadn’t been haunted by thoughts of what might have been, of what she might have been, both children would have tumbled from the blaze of newspaper headlines into the darkest reaches of infamy.

But none of them suspected anything of this on that wet November afternoon, just hours before their lives collided and cracked open to reveal the truth of them all.

Especially not Erdman Frith, who was dithering in the freezer section: aisle three for pepperoni and a pension; aisle five and he might as well be as dead as the lump of sirloin he was lifting into his cart.

No, Erdman Frith wasn’t thinking about death at all. He was more concerned with what Lilith would say when she saw . . . dum . . . dum . . . dummmmm . . . Red Meat.

Erdman pictured her, lips pursed tighter than a gnat’s arse.

“What about the saturated fat content, Erdman?”

“Doesn’t red meat contribute to bowel cancer, Erdman?”

The gnat’s arse would pucker.

“Or mad cow disease, Erdman. They claim they’ve eradicated it, but who’s to say they’re telling the truth?”

Did she honestly expect him to answer that?

Once upon a time he’d have teased the worry lines from her face, firing silly jokes at her until they were both laughing, and she would lean into him, fingers tangling his hair, breathing him in, her fears forgotten.

“Why do they call it PMS, Lilith?”

“I don’t know, Erdman, why do they call it PMS?”

“Because mad cow disease is already taken.”

Bada bing.

But these days he couldn’t even raise a smile.

These days, her eyes followed Jakey’s every move, her fears not forgotten, but amplified a thousandfold by a cruel enemy that was reducing their son—and now their marriage—into paper butterflies, fragile and easily broken.

They told their boy, Lilith and Erdman, that he had a little problem with his bones. That was something of an understatement. Jakey’s “little problem” would end up killing him.

The medical team who’d delivered him had suspected it immediately, thanks to the telltale malformation of his big toes. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Thirty-five letters. A letter, give or take, for each year Jakey was expected to live. The average life expectancy. Any more would be a bonus.

By chance, a nurse in the maternity unit had spent the previous six months working in an Australian hospital where a teenager had reported with strange bony growths and increased loss of movement. They’d injected painkilling drugs into her muscles, she’d explained, surgically removed the extra ribbons of bone, and all they had done was make it a million times worse. By the time she was diagnosed, she was practically a statue, barely able to move at all, except to speak. She could still speak. The nurse had told them that as if it was some kind of blessing.

Six years on, even the specialists were shocked at the speed of the progression of his illness. Jakey’s flare-ups were unusually severe for one so young. His body was following the characteristic path of the disease, but already it had reached his arms much earlier than they’d anticipated. A fall or a bump could trigger a life-threatening episode.

They were told to enjoy their time with their son.

Erdman’s fingers grazed the cool, damp packaging in his cart. He should put it back. Lilith would kill him and he didn’t want to upset her, not really. He longed for the joyous freedom of their love, before it was tangled up in hospital appointments and medications. But he was weary of always doing what she told him to do.

Anyhow, he didn’t have BSE or CJD, or whatever the hell it was, and he was pushing forty. If that metaphorical cowpat was heading his way, it would have dumped on his life by now, which, let’s be honest, was already shitty enough. Even if the worst did happen, he wouldn’t notice the transition from middle-aged man to vegetable. A potato had more fun than he did.

Fuck it. Jakey loved roast dinners and he needed building up.

Had Erdman known that he was sealing his son’s fate in that most glamorous of locations, Tesco on Lewisham Road, the whole family would have become vegetarian. But he didn’t, and so he headed home, smug in the knowledge that, as he had done the shopping, it was his prerogative to decide what they had for tea.

3.23 p.m.

“Ip dip doo. The cat’s got the flu, the monkey’s got the chicken pox, so out go you.”

Poppy Smith was pointing straight at her, giggling through the gap in the top row of her teeth, but Clara Foyle wasn’t smiling.

“Not playing,” said Clara, and turned her back on the small knot of children and their game of tag.

She marched off in the direction of the gates at the far end of the playground, her hands buried deep into her pockets. It was almost empty, just a few stragglers waiting for the older boys to finish an impromptu game of football. Poppy called after her, making lobster claws with her fingers, and everybody laughed, but Clara pretended not to hear. Poppy’s mother was supposed to be looking after Clara, but she was gossiping with another mother, her back to the little girl, and didn’t notice her wandering off while Poppy was too busy whispering with the others to see.

That was his first stroke of luck.

Mrs. Foyle called them scavengers, those playground mothers who gathered in impregnable clusters at the school gates every afternoon. To Clara, they looked like birds, with their bobbing heads and pink lipstick and pretty clothes. She didn’t know that some birds liked to pick clean the bones of other people’s lives.

Five minutes earlier, she’d tugged on Poppy’s mother’s coat and whispered that she needed to go to the toilet. Mrs. Smith hadn’t answered, but carried on talking, flapping her arms about like wings. Clara had squeezed her legs together and hopped about a bit, but now her tights were damp and chafed against her thighs when she walked.

“No, Mummy, I don’t like Poppy anymore,” she had whined to her mother that morning when Mrs. Foyle had explained who would be picking her up.

“I’m sorry, my darling, but it can’t be helped. You’ll have a lovely time. Anyway, it’s Gina’s afternoon off, and I’ve got an appointment.”

Clara had sulked and cried, but it had done no good. Her mother would not be swayed. To Mrs. Foyle, perfectly coiffed hair was more essential than breathing.

The wind flexed its muscles, skittering leaves across the playground. Clara was cold, and her head ached, and she wanted her mum. She patted her backpack to make sure her purse was still there. The children were not supposed to take money into school, but Clara had slipped it into her bag after breakfast, when Gina wasn’t looking. She liked the sound the coins made when they clanked together.

The chilly air pinched again. It made her think of her father, and the way he squeezed her cheeks between his fingers, leaving them reddened and sore.

Clara shivered and fumbled with the zipper of her coat. Mrs. Lewis, her homeroom teacher, caught her eye through the staff room window and waved. She lifted a shy hand in return, and shouldered her backpack, which was almost as big as she was.

The side gates stood open. Mr. Crofton, the caretaker, would lock them on his late-afternoon rounds, but for now the heavy metal bars were fixed in place against the green railings, the path to freedom unchallenged.

Between jackhammer thumps of her heartbeat, Clara slipped through the school gates and stood on the pavement outside. A shiver that had nothing to do with the wind tickled her insides. Quickly, she glanced back. Across the concrete expanse of the playground, Poppy was playing with Sasha, and Poppy’s mother was still talking and flapping. Three more steps, and Clara would be around the corner and out of sight.

The little girl grinned nervously to herself.

Across the road, a man in a black pin-striped jacket unfolded his body from the car that had been parked there every afternoon for two weeks. He also began to walk. His strides were longer than hers and he soon overtook Clara, but she was too intent on her own escape to notice him.

A few streets on, a woman coming out of a convenience store thought it was strange to see the girl walking home by herself through the Friday afternoon dusk. She registered Clara’s uniform hat, looked for an adult, and vaguely noted the man in the black pin-striped jacket. His eyes held hers, and in that frozen moment, she was reminded of her family’s elderly dog. He had died that summer after being eaten from the inside by maggots, an awful, prolonged death by fly-strike. When she had found Buddy, still alive but in shock, his eyes had been empty. As empty as this man’s. A powerful sense of revulsion overcame her, and the plastic bottle of milk she was carrying, slick with condensation from the cooler, began to slide from her fingers. The man looked away, and the woman remembered to tighten her grip before the milk hit the pavement and burst.

She forgot his face almost instantly.

The man turned into a shop next to the one the woman had just left. It was empty, save for the shopkeeper, who was talking on the phone in Punjabi, the hard line of his jawbone holding the receiver against his shoulder while he scribbled figures on a scrap of paper. He was calculating how much it would cost to install CCTV, and didn’t look up at his customer.

The jars drew Clara in behind him. She loved sweets, and here were rows and rows of brightly colored gobstoppers and toffees in shiny wrappers and cola bottles and chocolate raisins and rainbow crystals of every flavor.

One-two-three-four-five different colors, counted Clara in her head. Five. The same number as me.

Her stomach growled. Lunch had been almost four hours ago, and she had wrapped her turkey pie in a napkin and dropped it in the trash while Mrs. Goddard was shouting at Saffron Harvey for spilling peas all over the dining hall floor.

The man wearing a black coat stood in front of her. Because Clara was so small she could not see his face, just a five-pence-sized patch of what looked like rust intersecting the fine white stripes of his pocket. Even though she was young, she knew about rust, because her father had been complaining about the gardener letting the tools go rusty, and had shown her the rake. It wasn’t rust, though. It was dried blood. And she didn’t know anything about blood. Not yet.

“A quarter of Raspberry Ruffles, please,” he said.

When Clara left the shop a few moments later, clutching a paper bag of strawberry bonbons in one hand and her change in the other, the man was waiting outside, leaning against some railings.

“Whaddya get?” He was cheery, friendly, rifling through his own paper bag before selecting a sweet and removing its wrapper. He popped the chocolate into his mouth and grinned at the girl.

“Mmmm . . . delicious . . . do you want one?”

He shook the bag at her, and she took a step backwards. Her backpack bumped against the telegraph pole, making her stumble.

“S’okay, I won’t bite.”

The bag quivered again, and she leaned forward, suddenly entranced by the gleaming twists of pink. She reached out a hand to help herself, and the man’s bony fingers closed around her wrist.

“Mummy asked me to walk you home. ’Cos you don’t like the dark. Okay?”

With a shy nod, she allowed herself to be guided down the street, and towards a block with a row of crumbling garages. A late-afternoon mist was beginning to drift down, blurring the parked cars and the pavement ahead. Dusk was due at 4.09 p.m., and it was touching twenty to.

She sidled closer to the man, nervous of him, but more nervous still of the darkening day, the rapid leaching of color from sky. He turned to look at her, his eyes black clots.

The street was narrow with squat blocks of flats on either side. The buildings had no front gardens, just a concrete strip dotted with overflowing garbage cans. One or two of the upstairs flats were in darkness, but most of the downstairs ones had light blazing from their windows, and her eyes were drawn to the giant TV screens in more than one sitting room. Her tummy rumbled again, and she slid her left hand into her pocket and plucked out a bonbon. The pink dust left a trace on her fingertip. She sucked hard on its sweetness, which, for a moment, carried away the bitter, anxious taste in her mouth.

Clara lived on Pagoda Drive in Blackheath, an enclave of exclusive properties a world away from this neighbourhood, with its graffitied slide standing on a patch of scrubland. She had her own bedroom, painted in pink, and a matching wardrobe stuffed with Disney princess dresses. Sleeping Beauty was her favorite.

She tried to tell the man that she had changed her mind, that she would try to find her own way home, but he didn’t hear her. He was striding along, still gripping her wrist in his hand. When she tried to wriggle it free, his nails dug into the pale strip of flesh protruding from the cuff of her coat.

At the end of the empty street was a disused factory with several broken windows and a DO NOT ENTER sign. Parked in front was a dented grey Ford van with no windows.

The man turned to the girl, and this time there were no friendly crinkles around his eyes. Still holding her wrist, he waved his keys, and the van made a bleeping sound. He jerked his head towards it.

“Get in.” His voice was gruff.

Clara didn’t want to get in his van, so she shook her head and tried to pull away, but her small frame was no match for him. As she opened her mouth to scream, he wedged his hand between her teeth. She bit down hard. He did not cry out, but the anger was there in the threat of his eyes, the bruising of his fingers into delicate skin.

She was struggling and tried to kick her legs, like she’d been taught in swimming, but it was no good. The man put his other arm around her waist and hoisted her in. He climbed in behind her and slammed the doors.

Poppy’s mother, Mrs. Smith, noticed that Clara was gone about six minutes after she had left the playground. By the time she had scoured the school grounds, and used her mobile phone to call the police, the skies had darkened and the van was driving away.

5.56 p.m.

Two hours and seventeen minutes after Clara Foyle was abducted, Erdman sat down opposite his family. Lilith was cutting up Jakey’s carrots, her mouth a seam of displeasure; Jakey was singing under his breath, his mind elsewhere.

Erdman ran his fingers through his hair, or what was left of it, as dull as the paintwork on Jakey’s toy car. The one he’d left in the wading pool for two weeks, and was now next to useless.

Useless.

That was a word he was well acquainted with. He could never quite shake the feeling that he hadn’t lived up to expectations: his mother’s, Lilith’s, his own. He’d always convinced himself there was plenty of time, but as his waistline thickened and his hair thinned, he was uncomfortably aware that his life was, in all probability, closer to its end than its beginning.

Glancing at his son, Erdman’s heart gave a funny sort of jump. Jakey prompted in him a curious mixture of protectiveness and bafflement that, even after five years, he struggled to understand. Jakey’s lips moved, but Erdman couldn’t make out the words.

As he tried to find a way into the silence, Lilith grimaced at her plate. She’d worn the same expression in bed that morning when he’d accidentally stroked her thigh.

“Are you going to carve the meat or what?” The gnat’s arse shriveled. “I mean, really, who has roast dinner on a Friday night?”

The words of conciliation on his lips congealed. Appetite dwindling, he gazed at the beef, marbled with fat and running pinkish juices, and switched on the carving knife. Its low buzz reminded him of the noise he sometimes heard from the locked bathroom door, when Lilith announced she was having a soak, so could she have half an hour’s peace, please. He wished he hadn’t bothered to sneak home early and had gone to the pub instead.

Lilith was staring through rain-blurred windows into the dark square of their garden. He wanted to drag her back into his life, but he didn’t know how.

A memory surfaced, unexpectedly, of a pub lunch a couple of months after they’d met.

He’d always been wary of large groups, but she’d charmed his friends with funny stories from the school where she’d once worked. As they left, she’d slipped her hand into his, and he could still remember his absurd sense of pride.

God, he missed her.

Jakey’s singing went up several notches. It often did at mealtimes. Erdman wondered if it was his son’s way of drowning out the sound of a family’s disintegration.

“What’s that song?” said Lilith, her brow creasing.

“Shiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiit! I mean, ow, ouch.”

A burn of pain lit Erdman’s finger as the blade slipped and bit deep, its serrated teeth slicing through skin and subcutaneous tissue. Jakey stopped singing, saucer-eyed. The water in their glasses vibrated. Erdman’s empty plate was spattered with ruby droplets, like a grisly version of the Jackson Pollock he’d seen at the Tate last month.

The knife spun in frantic circles until Lilith switched it off. As Erdman staggered against her, he was briefly aware, for the first time in several months, of the fullness of her breasts.

After a few seconds, the heady sensation lifted, and he looked down at his hand, which she’d wrapped in a napkin after lowering him into the chair. He could have sworn the fabric was white, but now it was a vivid scarlet.

“Get Daddy some water,” said Lilith. The boy didn’t move. “Go on.”

With a six-year-old’s reluctance to leave the bloodied scene of the action, Jakey limped into the kitchen. As he reached the archway, he turned to look at his father. Erdman managed a smile. And a little wave. With his left hand, obviously.

It was starting to sting, his finger. Shit. Erdman rested his injured hand on his thigh while Lilith lifted a corner of the damp linen. Fresh blood plip-plipped with purpose, speckling the pale laminate floorboards. He couldn’t bring himself to look at the cut, that thick flap of ruined skin. Lilith’s sharp intake of breath told him all he needed to know.

Outside, a car alarm went off.

Not a car alarm.

Jakey.

Lilith dropped his hand and sprinted towards the kitchen. When Erdman stood, the walls rippled like the inside of a swimming pool. As soon as they’d stopped moving, he stumbled after her. His heart filled his mouth at the scene before him.

Jakey was sprawled across the floor, one arm beneath his body, the other stretched out in front of him. His head was twisted on its side. A stool had been tipped over. Fragments of glass were strewn across the tiles, and water was pooling near the oven.

Lilith’s face was stricken, guilt and fear and accusation rolling across her features. Jakey was struggling to sit up, gulping and crying.

“Nice and easy does it, sweetheart,” said Lilith.

Pushing aside his own pain, Erdman held out his uninjured hand to his son.

“Where does it hurt, champ?”

Jakey didn’t reach for his father as he usually would. Instead he drew in a shuddering breath, winced, and began to cry again. For the briefest of moments, Erdman’s eyes met Lilith’s.

“My arm, Daddy,” he said, through a waterfall of tears. “I fell on my arm.”

As Lilith helped Jakey to his feet, Erdman was assessing the damage. Jakey’s working arm, the one he used to eat and drink and play and write, was now hanging by his side at an odd, awkward angle. Already, it was beginning to swell, and reminded Erdman of a fat pink sausage, about to burst its skin. The other arm, rigid and unyielding, was drawn in at the elbow, fixed in that position since Jakey was three.

“Anywhere else, Jakey?” he said. “Did you bump your head? Fall on your knees? What about your ribs? You need to be careful when you’re using your stool—we’ve told you that a hundred times before. Didn’t you use the handrails? Why didn’t you get the bottled water from the fridge?”

His son’s bottom lip quivered, and he began to sob again, noisily and messily. From the way Lilith was glaring at him, Erdman knew he’d pushed it too far. Jakey still hadn’t moved his arm, and now it was a strange, mottled purple.

“Sit down, sweetie,” said Lilith. “I’ll get you a drink. And one of those biscuits you like.”

Lilith’s whisper was hot in Erdman’s ear as she reached into the cupboard behind him for a glass. For a moment, he remembered the feel of her mouth on him, but the pain in his hand and concern for Jakey pulled him back to the present.

“Listen, you need stitches. It’s a deep cut. Nasty. And I don’t want to scare Jakey, but we’d better get him down to the ER, too. I’ll give him his steroids now, but he’ll probably need an X-ray.” Her own mouth trembled. “I think his arm is broken.”

Erdman groaned, regretting the wasted meal, but truth be told, his appetite had deserted him.

Jakey swallowed down the anti-inflammatory. His tears had quieted, but now they tracked silently down his face. Using his good arm, Erdman hoisted his son onto his hip, careful not to knock him. After a few seconds, his bicep started to ache, but he ignored it and carried Jakey outside to the car. The security light flicked on, the blood from Erdman’s hand leaving a trail of spots on the driveway. His son shifted in his arms to look at them.

“Are you going to die?” Jakey’s face was a pale moon against the winter night sky.

“’Course not, champ,” said Erdman. He buckled Jakey into his seat and kissed his hair. “Daddy just needs a couple of tiny stitches.” He forced his voice to steady. “And we need to get you checked over. Can’t have you with a bad arm.”

As Lilith drove them to the hospital, Jakey began to sing again. His voice was quiet, but Erdman was sitting next to him in the back, and could make out his son’s clear notes above the drone of traffic.

Unlike Lilith, he did recognize the song that Jakey was singing. He recognized it, because Carlton—Erdman’s brother—had sung it with him when they were little.

And Carlton had been dead for thirty-six years.

At the Royal Southern, Jakey and Lilith were directed to the children’s emergency room, while Erdman had to wait an hour for a harassed intern to inspect his wound. His name tag announced him as Dr. Hassan.

“It looks like you’ve nicked the bone, but I don’t think you’ve damaged the tendon.” He peeled off his latex gloves. “It’ll probably ache for a few days, but you did the right thing by coming in. It’ll heal faster with stitches.”

The curtain swished and Lilith’s head poked around. Erdman could see her knuckles were white with the effort of pushing Jakey in his hospital-issue wheelchair.

In summer, the merest hint of sun made his freckles pop like a dot-to-dot puzzle. That November night, the 16th, Jakey’s skin was completely colorless, as if the network of veins and vessels just below the surface was filled with milk.

“Sorry,” she mouthed at the doctor. “I just wanted to let my husband know what’s happening with our son.” She didn’t wait for permission to speak, but she was smiling. “They don’t think it’s broken, but he’s going for an X-ray, just to be sure.”

The balled fist in the pit of Erdman’s stomach unclenched.

“Seriously? But it looked so . . .” He was aware of Jakey’s eyes on him. “That’s really great.”

“I was just telling your husband he needs some stitches,” said Dr. Hassan.

There it was, that word again. Erdman concentrated on keeping down his lunch, and tried to ignore the thumping in his ears. Sweat beaded his upper lip. He shut his eyes. He knew he looked like shit.

“He’s funny with needles,” said Lilith. “And blood. He fainted when Jakey was born. They had to whisk him off in a wheelchair. Took him a good couple of hours to recover.” She leaned over and squeezed Erdman’s knee, to take the sting from her words.

Dr. Hassan chuckled and patted Erdman on the back. “Happens to the best of us, my friend. I fainted the first time I saw a postmortem.”

“What’s a postmortem?” asked Jakey, his eyes bright with interest.

“Well, young man, it’s when—”

Lilith interrupted the doctor. “It’s just a medical procedure, darling. Now, let’s get you down to X-ray, and then we’ll see about getting you something to eat.”

6.01 p.m.

Clara’s mouth was pressed hard against something rough, and with every jolt, it rubbed the skin in the dip of her chin. Her wrists were tied behind her back with a length of surgical tape that crisscrossed the scant flesh. The binding cut deep between her thumb and her finger.

The van was flying over bumps, its tail end thumping down heavily after every descent, and the pain in her chin and the strangeness of the situation were making the muscles of her stomach tighten. Clara was usually a child who cried easily, but for once the tears did not come. A kind of numbness had set in.

The man had propped her against a box, and she was wedged between two rolls of carpet. There was a strong smell in the back, like butchered meat left to rot. It was cold and dark, and she couldn’t see.

Something crawled over her cheek. She wanted to scream, but the man had said he would kill her mother if she did. Clara believed him. He had been smiling when he said it, just before he had shut the van doors, but she knew it wasn’t a joke.

Her stomach rumbled again. During afternoon break, Poppy had told Clara they were having sausages and chips for tea. Clara’s mother never let her eat food like that. The van juddered again. Her thoughts flitted back to her mother: pink nails and thick black eyeliner, and the way she pushed her glasses up the bridge of her nose whenever she scolded Clara, the way she pressed her cheek against Clara’s in a facsimile of warmth, but always maintained a gap between their bodies. Mrs. Foyle didn’t like sticky faces and hands.

The van stopped and then jolted, before the rumble of the engine died away. There was a tick-ticking sound as it cooled. A loud, metallic clunk made her jump, and Clara realized it was the van doors sliding open. A bulb without a shade dangled from the ceiling, and it gave off just enough light for her to see she was inside a garage.

This garage belonged to a house, tall and thin like the man who had taken her. She couldn’t see it, but the house had small, shuttered windows and a handrail flanking steps leading down to a basement. A path of cracked black-and-white tiles, woven with weeds, led to a front door, where blue paint had peeled off and left patches shaped like countries. A wrought-iron number 2, dulled from age or weather, had lost a screw, and hung upside down, an inverted cedilla. Spits of freezing rain landed on the pavement. Almost completely d. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...