- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

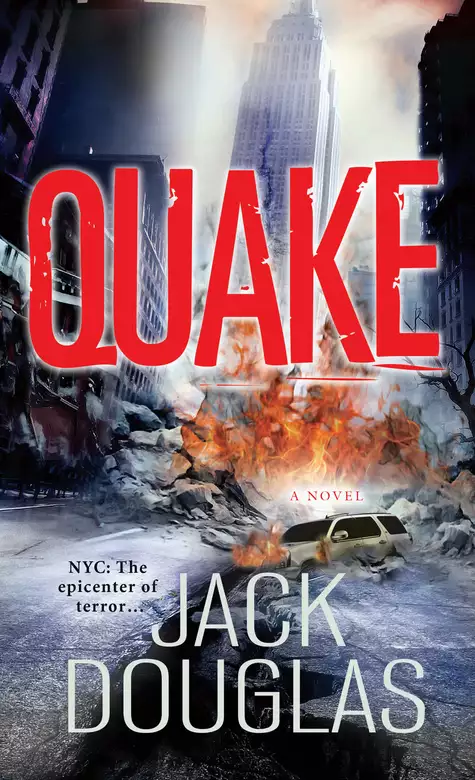

Quake is a disaster novel of epic proportions that will have listeners thinking twice about their next trip to New York City.

New York City has seen its share of disasters: terrorist attacks, blackouts, hurricanes, floods. But nothing has prepared the Big Apple for the biggest earthquake to ever hit the United States—9.0 on the Richter scale. Manhattan and the surrounding boroughs are a smoldering catastrophe, plunging New York into terrifying chaos. Skyscrapers and bridges have collapsed, killing hundreds of thousands. For a handful of survivors, the nightmare is just beginning.

Clawing north, navigating the ruined city amid violent aftershocks, FBI agent Francisco Mendoza hopes to reunite with his wife. Assistant US Attorney Nick Dykstra is hell-bent on finding his daughter way uptown at Columbia University—before a 9/11 conspirator who escaped during the quake finds her first. But the Indian Point nuclear power plant, forty miles north, is severely damaged. A deadly cloud of radiation is drifting toward the city. The only chance for survival is going down into the subways—and deeper still.

Release date: August 5, 2014

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Quake

Jack Douglas

Catchy, Nick thought. But far from the best I’ve heard outside 500 Pearl.

Nick kept his head down. Not that he thought he’d be recognized; the Honorable Justice Kaye Gaydos had rightly banned cameras from the courtroom for the duration of the case, leaving the public with little more than 1980s-style courtroom illustrations to gawk at when they tuned in to CNN after work to catch their highlights of the day’s trial testimony. And the courtroom sketches—created by artists hanging on to an all-but-obsolete trade—hardly did Nick justice. At least in his opinion.

Besides, it was the defense attorneys who were the glory seekers; they had everything to gain and nothing to lose by grandstanding. Career prosecutors like Nick didn’t give a damn what the general public thought of them, so long as their higher-ups caught the full show. Particularly the president of the United States; or future presidents to be more precise. No matter what happened at this trial, Nick thought it was highly unlikely that he would be appointed as a U.S. attorney or federal judge within the next two years. And by January 2017, when the next U.S. president took office, this trial would be long forgotten by everyone but its participants.

Unless I nail Alivi with the death penalty, Nick mused as he shoved his way through the crowd. That would keep the trial and the defendant in the minds of the American public for years to come. Years of appeals by Alivi and his lawyers would keep Nick’s name in the transcripts and the New York tabloids, if not the national TV news.

As Nick approached the makeshift gate, the protestors morphed into journalists, and for a moment Nick wondered which were worse. The protestors at least had a legitimate gripe, even if Nick didn’t agree with them. Hell, they were New Yorkers, and Feroz Saeed Alivi was one of the last men to be captured and charged for his role in the death and destruction that took place just a few city blocks away on September 11, 2001. And here he was, Feroz Saeed Alivi on American soil. Here he was, in New York City. In downtown Manhattan for Christ’s sake, just a five-minute subway ride from Ground Zero. About to receive a fair trial with all the rights and privileges afforded your average American citizen.

The protestors had wanted Alivi to be tried as an enemy combatant in private at Gitmo. Osama bin Laden and the rest of the self-proclaimed jihadists who attacked the United States twelve years ago had been in the spotlight long enough; these protestors wanted them thrust back into the shadows, where they belonged. This trial, they claimed, was opening freshly healed wounds and giving Alivi the world stage yet again. In the realm of radical Islam, Alivi was being heralded as a genuine hero and a martyr to the cause.

I’ll make damn sure he’s a martyr, Nick thought as he approached the U.S. marshals guarding the gate. There were four of them and they were armed with assault rifles. Just in case someone somehow made it past the line of NYPD officers dressed in full riot gear, which Nick thought highly unlikely, if not impossible. Then again, the Boston Marathon bombing had managed to put New York on edge again, even if its impact on the nation as a whole was relatively minor and short-lived.

Nick Dykstra dipped into his suit jacket and fished out his attorney ID, flashed it to the marshals who parted the gates and allowed him through. That’s when Nick was finally recognized, at least by members of the press. The press. The once noble profession was noble no more, in Nick’s opinion. Over the past two decades the twenty-four-hour cable news networks had gleefully reduced the profession of Edward R. Murrow to an around-the-clock reality show that better served as a punch line for late-night talk show hosts than as a serious source for information on current national and global affairs. So Nick wasn’t the least bit surprised when reporters started barking questions at him as though they were at a mock press conference being held in a high school gymnasium rather than standing in front of a federal courthouse during one of the most important trials of the new century.

“Counselor, what do you say to the hundreds, maybe thousands, of New Yorkers out here today demanding that the defendant be sent back to Guantanamo Bay for a military tribunal?”

Nick turned toward the closest camera and said, “No comment,” then thought, What the hell, and spun on his heels to face the music.

Nick raised his voice as much as he could so that he could be heard over the hecklers. “Actually, I say the jury has already been selected and sworn, and that, like it or not, opening statements in this trial begin this morning. I understand the protesters’ gripe and certainly sympathize with them, but at this stage in the game I’m afraid it’s a moot point.”

“But do you think this is the proper forum?”

Nick strained his voice again. “I can think of no better place to achieve justice for the American public than in a United States federal courthouse, particularly here in New York City where the damage Alivi did was felt so deeply.”

“Are you promising New Yorkers here that you’ll win a conviction?”

“I’m promising that I will damn well try.”

Nick had turned and started through the gate toward the concrete steps when he heard one last question he felt compelled to answer.

“How confident are you that Alivi will receive the death penalty?”

“Confident enough,” Nick shouted back over his shoulder, “that I’ve already picked out the suit I’m going to wear to his execution.”

There’s your sound bite, he thought as he hurried up the steps toward the heavy double glass doors. He turned once more to take a look at the scene. A mob of New Yorkers gathered in front of 500 Pearl for a good (albeit misguided) cause. He glanced up. The sun had already risen high over the skyscrapers and it was promising to be another perfect autumn day.

If only they knew, he thought. If only they knew that Assistant U.S. Attorney Nick Dykstra had as much riding on this trial as anyone. And that the stakes for Nick had absolutely nothing to do with his career as a federal prosecutor. If only they knew that among the nearly three thousand victims at the World Trade Center on that hellish day twelve years ago was Sara Baines-Dykstra, Nick’s late wife and the mother of his only child, his beautiful seventeen-year-old-daughter Lauren—the only light left in Nick’s life.

Nick had been downright ecstatic when the U.S. attorney general announced that Feroz Saeed Alivi would be tried on American soil, following his capture fourteen months ago by authorities in Yemen. Even more so when his boss, U.S. Attorney of the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara, called Nick into his office and told him that Nick would serve as lead counsel if the case ever made it to trial.

Because for AUSA Nick Dykstra, this defendant wasn’t just another criminal. He wasn’t just another terrorist. For Nick Dykstra, the case of The United States of America versus Feroz Saeed Alivi wasn’t just another trial. For Nick, this was personal. And Nick had months ago vowed that he would personally send Feroz Saeed Alivi to his death, in order to avenge his wife, Sara, and to finally gain a scintilla of closure for himself, for his beloved daughter, Lauren, for his city, and for the rest of the nation.

The courtroom was packed but under control. Dozens of voices competed for vocal superiority, but not one exceeded the decibel level appropriate for a federal courtroom. State courthouses in New York City all but invited chaos; judges shouted, court officers dozed, lawyers often arrived at court disheveled and unshaven, reeking of alcohol, dressed in suits they’d probably slept in. But federal courthouses commanded respect. Even with no judge sitting at the bench, lawyers refrained from shuffling newspapers; journalists chatted as softly as though they were in a church; and the public spectators sat quietly with their hands in their laps, feeling lucky simply to have gotten a seat to the show.

By the time Assistant U.S. Attorney Nick Dykstra walked through the tall, mahogany double doors, most of the stage was already set. The wood was meticulously polished, the marble almost sparkling. The fine maroon carpet appeared as though it hadn’t been treaded upon by a single pair of shoes, let alone the dozens of spectators who had entered the courtroom before him.

Nick’s second seat, AUSA Wendy Lin, stood at the prosecutor’s table sorting through the massive file, much of which remained classified. Two prosecutorial assistants, one male and one female, sat just behind her, alternating between anxiously tapping their feet and biting their nails.

Nick walked slowly up the aisle of the public gallery, the briefcase in his hand largely for show. Inside were some handwritten notes, which he’d neither need nor use in his opening statement to the jury.

The moment Nick stepped past the rail he was accosted by Kermit Jansing, lead counsel for the defense. Jansing was a smarmy character who looked as though he just stepped out of a Grisham novel. At five and a half feet, his eyes always seemed to lock on Nick’s throat, which never ceased to send a shiver up Nick’s spine. Meanwhile, Nick could almost check his reflection in Jansing’s shiny scalp.

“Good morning, counselor,” Jansing said loud enough for the press in the front two rows of the gallery to hear. He stuck out a sweaty palm and Nick grudgingly took it in his own.

“Kermit,” Nick said, unable to mask his distaste. “Nice suit.”

Jansing took a step back to allow Nick to take in the entire package. The suit, which was a charcoal three-piece with thin pinstripes, would have better befit a wiseguy on his way to getting made than an officer of the court about to deliver an opening statement in defense of one of the world’s most notorious terrorists. But Nick let the little guy have his moment. The suit probably cost Jansing a couple grand, or two hours’ work on behalf of one of his many white collar clients on Wall Street, depending on how you looked at it.

Jansing turned back toward the defense table, where a young female associate sat waiting. She was at least four inches taller than Jansing, beautiful, with long, shimmering blond hair and a pants suit two sizes too tight. Nick guessed she was probably just out of law school. Given Jansing’s track record, she wouldn’t last the month before the eww factor kicked in and she ran for the hills, a victim of one of Jansing’s impromptu attempts at a neck massage.

“Morning, Wendy,” Nick said to AUSA Lin as he set his briefcase down on the table. “Wedding day jitters?”

She forced a smile at the inside joke. Her fiancé, Brett, hadn’t thought it so funny when following the U.S. attorney’s office softball game, she admitted (after three too many drinks) that she was more excited and better prepared for Alivi’s trial than she was for her own nuptials one month later.

“I was listening to the news on the way into the city this morning,” she said. “The NTAS issued an elevated alert for the metropolitan area.”

Homeland Security’s National Terrorism Advisory System (NTAS) had replaced the color-coded Homeland Security Advisory System a couple of years back, and while definitely an improvement, it still managed to rattle citizens even when there was no credible or imminent threat. New Yorkers, Washingtonians, and now Bostonians were particularly frazzled by such announcements. And this one was no doubt precipitated by the mere fact that Feroz Saeed Alivi’s trial was beginning in earnest today. The elevated threat level gave ammunition to critics who warned that Alivi’s trial in a civilian court would jeopardize the lives of millions of Americans. No doubt the advisory had also served to further fuel the protests Nick had passed through outside the courthouse.

“I don’t think there’s anything to worry about, Wendy,” Nick said. “The most significant threat to our national security is about to be escorted into this courtroom in shackles by six armed U.S. marshals.”

No sooner than Nick said it than the side door from the lockup area opened onto the courtroom. In the center of the half-dozen marshals staggered a dark, bearded man of six feet and maybe a hundred and fifty pounds soaking wet. Either Alivi had gone on a hunger strike, or the Metropolitan Correctional Center had severely cut back on the portion sizes of prisoners’ meals. The religious robe Alivi wore could have fit both him and his lead defense counsel at the same time.

“There’s your boogeyman,” Nick said to Wendy. “Still worried?”

As though Alivi heard him, the terrorist turned his head and leveled his gaze on the federal prosecutor across the aisle. Nick held his stare, his eyes narrowing, neck reddening in unadulterated hatred.

Looking forward to seeing those eyes while they stick the needle in your arm, you vicious little bastard, Nick thought.

Then he cleared his throat, looked away, and took a seat next to Wendy. Having seen Alivi again up close, Nick couldn’t help but think of his wife Sara’s final moments on the eighty-fourth floor of the South Tower. For the past twelve years, they’d flash uninvited in his mind like summer lightning. He’d hear her voice as he had through the phone that morning while he sat in his office. His pulse would race and he’d become short of breath and he’d begin to sweat as though he was once again rushing across town in a futile effort to save Sara.

Just as suddenly he’d snap out of it.

“Please rise,” Justice Gaydos’s clerk intoned from in front of the bench.

Nick and Wendy stood as one as the courtroom fell silent.

“The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York is now in session. The Honorable Justice Kaye Katrina Gaydos presiding.”

Regal in both posture and black flowing robe, Justice Gaydos blew into the courtroom like a hard wind, her face completely devoid of emotion.

“Be seated,” she said as she climbed to the bench.

Nick made the mistake of again glancing across the aisle. Once more he caught the malevolent gaze of the bearded defendant, Feroz Saeed Alivi, and once more he froze as visions of the Twin Towers crumbling before him came unbidden into his mind.

“Nick, we can’t—” Sara’s voice cut in and out. “We’re too high up. We can’t evacuate. Oh, God, Nick, the office is filling with black smoke. There’s a fire. . . .”

Nick could never remember what he said in reply to her. He could only remember how he felt. As though someone had reached inside his chest and with all their strength squeezed his racing heart.

“I love you, Nick. I love you. I . . . have to go now. P-please, please tell Lauren I love her, and that I’ll always be with her. . . .”

Sara had trailed off, her voice replaced by some monstrous sound Nick now knew to be the bending—the shrieking—of immense beams of steel in unthinkable temperatures and under an unfathomable weight.

And then, nothing.

Justice Gaydos asked the clerk to call the first case.

The clerk rose and said, “The United States of America versus Feroz Saeed Alivi.”

Justice Gaydos said, “Attorneys, please make your appearances.”

Nick steadied his legs and rose to his feet, summoning all the power he could muster to strengthen his voice.

“For the United States government,” he boomed, “Assistant U.S. Attorney Nicholas Michael Dykstra.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Nick said as he paced the length of the jury box, “you will be burdened with an extraordinary responsibility in the days and weeks to come. As you well know, the man sitting with his attorneys at the far table is no ordinary defendant. He stands before this court charged in connection with one of the most heinous and cowardly acts in human history. The defendant in this case is charged with mass murder; mass murder and conspiracy to murder thousands of American citizens, right here, on our front doorstep. In our city. The defendant stands before this court to face responsibility for his role in the September 11, 2001, attacks on our nation. And it will be your awesome responsibility at the conclusion of this trial to bring justice to this man for the nearly three thousand souls lost at the World Trade Center here in New York City, at the Pentagon in our nation’s capital, and in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where a group of courageous American passengers, not so unlike yourselves, perished in a horrific plane crash while attempting to overcome their armed hijackers in order to save not only their own lives but the lives of countless others below.”

Within minutes of beginning his opening statement, Nick had settled into a rhythm. He had practiced this opening in front of a mirror in his home on the Upper West Side more times than he could possibly remember. Because he knew he’d need to keep his emotions under control. He wanted to speak to this jury with passion and zeal, but not with the all-consuming grief of a widower who had lost his wife and the mother of his only child. He needed to speak to this jury first as a representative for his country, and second as a New Yorker. The jury needed to know that what was at stake for him was at stake for each of them, and all American citizens and their allies around the world.

As the first hour passed, Nick went on to describe in vivid detail the physical and circumstantial evidence against Feroz Saeed Alivi—recorded messages, intercepted letters and e-mails, photographs, and lengthy confessions. He reminded these twelve men and women what they needed no reminder of—the horror and devastation caused by the attacks twelve years ago on a beautiful September morning, much like this one. He spoke of the aftermath, of the toll on survivors, and this he could describe all too well, because it seemed as though he could recall every moment of his own pain and suffering, every word uttered by his then five-year-old daughter, Lauren, who was trying so hard to understand why she would never again see her mother, and why anyone in the world would have wanted to take her mother away from them.

Nick talked about the years of training and planning that went into the September 11 attacks. The acts the defendant engaged in were cold-blooded and premeditated, the plans worked and reworked to cause maximum pain and suffering to the United States of America and her citizens. Nick touched briefly on the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and assured the seven men and five women of the jury that while their Al-Qaeda enemies were decimated and on the run, the threat they posed to New York and all American cities remained very real.

In the second hour, Nick spoke of the witnesses who would present testimony against the defendant in the days and weeks to follow. Investigators from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and yes, even a few of New York’s Finest would take the stand.

Throughout his opening, despite what the legal pundits had repeatedly said, Nick never once allowed himself to feel as though all of this was unnecessary, and that any third-year law student could try and convict a defendant like Feroz Saeed Alivi. Nick understood the importance of this trial to human history, and its psychological impact not only on himself and Lauren, but on everyone who had been touched by the events of September 11, 2001. And yes, Nick had an agenda that went well past a conviction on all counts contained in the book-length indictment. Nick wanted—no, he needed—for Feroz Saeed Alivi to die at the hands of the United States government. Nick was under no illusion; for the first time in his career, he wanted blood. He wanted to witness firsthand Feroz Saeed Alivi’s ultimate demise by lethal injection.

Throughout his adult life, Nick had struggled with his feelings about the death penalty. Given the opportunity, he could passionately argue either side. But in the past twelve months, since Alivi’s capture in Yemen and Nick’s appointment as lead counsel, Nick had read and heard and observed evidence that left no doubt in his mind that capital punishment was right and just under certain circumstances. And this case certainly qualified. Not only because of the carnage Alivi and his cohorts inflicted on this country more than a decade ago, but because he was unrepentant, and because he continued, even after his capture, to make threats against American citizens and their allies and interests around the globe. And yes, because some of those threats had been directed specifically at Nick himself, in his capacity as a federal prosecutor. And because those threats hadn’t been limited to him, but included the only person he had left on this earth. Threats that had included his seventeen-year-old daughter, Lauren.

For the past year, Nick had lived in a constant state of terror. It had started with anonymous letters in his home mailbox and was followed by e-mails from self-proclaimed jihadists. After a few weeks, Nick’s office phone began ringing. Weeks later, his home phone. After Nick had his number changed, his cell phone was compromised. And then his daughter’s. That’s when Nick got angry. Livid. That’s when Nick first demanded a face-to-face meeting with Feroz Saeed Alivi.

“Not going to happen,” Kermit Jansing told him one day over the phone.

In a barely controlled rage, Nick shouted, “You tell your client to lay the hell off my family, or I’ll . . .”

“Or you’ll what?”

Nick finally realized how helpless he was. Alivi, though behind bars, was provided more protection than any other inmate in the history of the United States. Alivi couldn’t communicate with the outside world except through his lawyers. So he couldn’t be pulling the strings; he couldn’t be threatening Nick and his daughter through his associates in the United States and abroad. Or could he? Was Kermit Jansing—wittingly or unwittingly—carrying coded messages on behalf of his client? There was no way to know. The attorney-client privilege rigidly protected all communications exchanged between the two men. For a while Nick began to wonder whether bringing Feroz Saeed Alivi to trial in New York City had been the right call by the U.S. attorney general after all.

But no, as time went on, Nick refused to be intimidated. When his boss, U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara offered to replace Nick on the case, Nick flew into a frenzy. This was his case, his conviction. And he wouldn’t be frightened off.

During the summer months, as the threats became greater and more specific, Nick finally accepted protection from the FBI and New York Police Department. “Don’t watch me,” he told the special agent in charge of his family’s safety, “watch Lauren. Make sure she’s protected at all times, day and night.”

If anything happens to Lauren, he’d thought grimly, I won’t be able to go on.

But nothing happened. Alivi’s people, it turned out, were all bark and bluster. And now the long run-up to the trial was finally over. Here he was, standing in a lavish courtroom at 500 Pearl, delivering his opening remarks to the jury that would ultimately convict this world-infamous terrorist who had played a major role in the attacks that had torn apart Nick’s family.

As the morning wore on, AUSA Nick Dykstra grew more confident and more relaxed. He hadn’t just settled into his rhythm; he was in a zone. The twelve men and women sitting before him were captivated. At various points in his opening, one or more jurors even had tears in her eyes.

“And so,” Nick said, “at the conclusion of this case, I’ll return to this rail, and having fulfilled each and every promise I made to you this morning during my opening, I will ask you to once and for all consign this madman to the dustbin of history. After you have seen all the evidence and heard all the testimony, I will return to you in my summation and ask—”

The softest rumble seemed to emanate from the walls. The sound echoed throughout the gallery, rose until it ricocheted off the sides of the vaulted ceiling. The chandeliers overhead shook briefly, their jingle like a wind chime before a storm.

During the vibration, Nick turned to look at Wendy, whose eyes had gone wide with fright. When nothing more happened, her face slowly returned to normal and he looked back at the juy, expressionless.

Nick was at a pivotal point in his opening and he was afraid to lose his rhythm so he began his last sentence from the top.

“After you have seen all the evidence and heard all the testimony, I will return to you in my summation and ask you to go into your deliberations with—”

The floor beneath Nick’s feet shifted ever so slightly. It felt as though a pair of mice had skittered under the soles of his shoes.

After a momentary hesitation, he continued. “After you have seen all the evidence and heard all the testimony, I will return to you in my summation and ask you to go into your deliberations with one image at the forefront of your minds—”

Then it happened.

This time there was no mistaking it.

Abruptly, the entire courtroom began to shake.

While Assistant U.S. Attorney Nick Dykstra delivered his opening statement i. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...