Herself

There I was, finally, at the Hotel Étoile. It said no vacancies on the door but I went in anyway and asked for a room. They gave me one on the tenth floor: view of the cemetery, Italian marble bath, Louis XVI writing desk, raft-sized bed the pillows of which were encrusted with little bonbons in burnished wrappers, like rhinestones in the snow. I told the concierge my husband was going to be along later with the luggage, but my husband wasn’t ever going to be along. I’m not a person to lie to someone’s face but in this instance it was out of my hands.

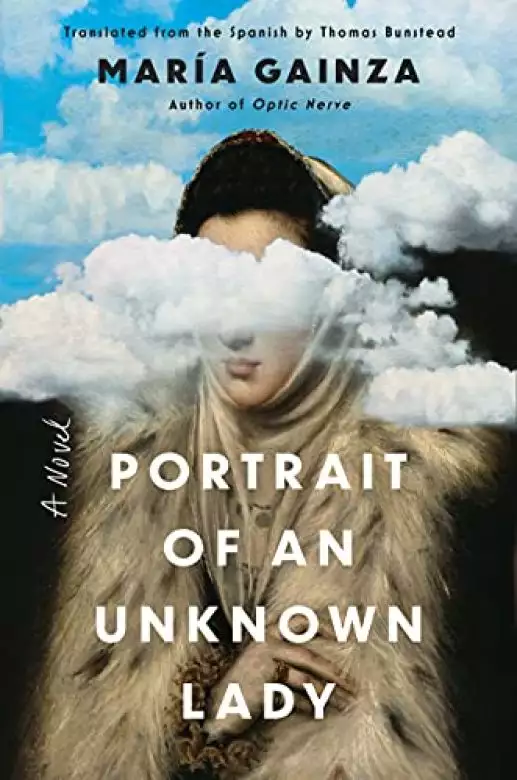

I checked in under the made-up name of María Lydis. Nobody asked for any papers; had they done so, they might perhaps have recognized the art critic I once was. But with the collar of my mangy black fur coat up around my ears, who was going to pick out the somebody I’d been in the art world, even if it was a fairly prestigious somebody? A claim justified by the idea, however wishful, that a delicate prose style may signify honesty; that style and character are indivisible.

I was going to confine myself to that Imperial Room—so called on the bronze panel over the walnut door—and give free rein to the inner hackette we all bear inside. The only way for me to turn the page, to start afresh, was to write down what I knew. My model being the eighteenth-century practice among the English, as described in Defoe’s Moll Flanders, of allowing the condemned to recount their crimes before being hauled off to the gallows.

Any person reading this ought not to expect names, numbers, or dates. The stuff of my tale has slipped through my fingers, all that remains now is a little of the atmosphere; my techniques are those of the impressionist, and not even the neo- kind. On top of which, my years in the art world have made me wary. I have only distrust for historians coercing the reader with the precision of facts, all those cold, crabbed notes at the foot of the page. “It was so,” they say. I am at the point where it is the nicer distinctions I appreciate, and I prefer for people to say, “Let us suppose it was so.”

I was born with a skewed smile. A weakness in my muscles means the left corner of my mouth never reaches quite so high as the loftier right. Duplicitousness, people say this is a sign of, an underhand nature—like the good man who turned thief because his shoulders, when he walked, evinced the languor of a cat. And when people say a thing, and then repeat it and repeat it, eventually one does come to believe it. If there’s anything that could be said to define the way I am today, it’s a general jitteriness. Very early in life, for reasons not to the point, I gave up any hopes I might have stored in either men or women. And in any case, those of my own sex have always been guarded in my presence. There has only ever been one woman who put her trust in me, which made me feel valued, and to people who do that, one owes everything.

We first met in the offices of Ciudad Bank, in the fine art valuations department. Enriqueta began working there in the 1960s as a cum laudegraduate of the Argentinean Fine Arts Academy. I had gotten a job through friends of the family, which in my time was the way jobs were got.

At a Christmas get-together a couple of years ago, my uncle Richard stood up and, in a booming drunken slur, announced that what our very own black sheep needed was a job, that it was the only way to whip her into shape. My uncle’s intelligence and clichés have always been a good match. A start in the world was the last thing on my mind. In fact, my personal credo consisted of a firm commitment to drifting along, to avoiding ties with anyone or anything. In the family, however, I was deemed a lost cause, and the best I could hope for was to excel as a catcher of butterflies. I don’t know why exactly, but for some reason I decided to accept the challenge. Probably to shut Uncle Richard up. So it was that a drunken conversation led to me starting work as the personal slave of Enriqueta Macedo.

It was nine o’clock in the morning on the first Monday in January when I opened the glass door at Ciudad Bank and approached the female receptionist sitting on the far side of a glass counter. She wore no bra, for all that that particular battle had long since been won, and when I said Señorita Macedo was expecting me, her raised eyebrows suggested that a mauling was not beyond the realms of possibility. She directed me to another glass door. The prevalence of that material stood out to me; an attempt perhaps to give the impression of transparency in the dealings of the institution it housed.

There was no need to ask whether she was she. Enriqueta Macedo was the country’s preeminent expert in art authentication, a true great of the art world, and when I went in I found her crouching close up to a painting on the wall, about to dive into it. She didn’t so much appear to be looking at it as to be taking in its scent. I cleared my throat, timidly, like people in the movies. She got to her feet, surprisingly supple for a woman her age, and raised her chin to beckon me. (This haughty gesture, I later realized, was a way of lifting her sagging neck skin.) She wore a lemon-yellow blouse and a creased, steel-gray trouser suit. On the outside unremarkable, a touch preposterous, even, but, as I would later realize, it was an exterior to belie what lay within.

I immediately did as instructed and went over. There was something of the hospital scanner in the way her eyes looked me up and down. Since I found it impossible to hold her gaze, I opted to look at my feet, just black blots on the floor. She spoke before I had a chance to think.

“Well, I hope you’ve done your homework.”

I flickered one of my lopsided smiles at her, the asymmetry of which might have amused, pained, or come as a relief to her. Enriqueta gave a commiserative click of the tongue and led me over to her desk.

“Don’t mind my little games. Always looking for a fight! Seems I can’t help it. Now,” she said, indicating a pile of twenty or so black folders, “your first assignment. Family secrets.”

Like a frock coat worn to conceal a belly too big, the folders held the invoices for every painting deposited with the bank over the course of several months. I began looking through the seemingly endless paper trail, and, when I grew weary of feigning interest, resigned myself to my fate. I would get used to it, I said. It’s remarkable how quickly we can get used to anything.

I was twenty-five and had landed a job in the most distinguished valuations department in the country: the single, despotic authority on the price and authenticity of all paintings then being bought or sold across the land, and a kind of upmarket pawnshop and storage-space provider any time there was a legal dispute over an artwork. Despite any apparent mystique, from the inside it was a darkly governmental kind of place, soul-sapping in its grayness.

A diffuse sensation of distress occasionally gripped me. All the talk was of profit margins, and the employees spoke a language I could only partially follow—as though just the single units of speech, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved