- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

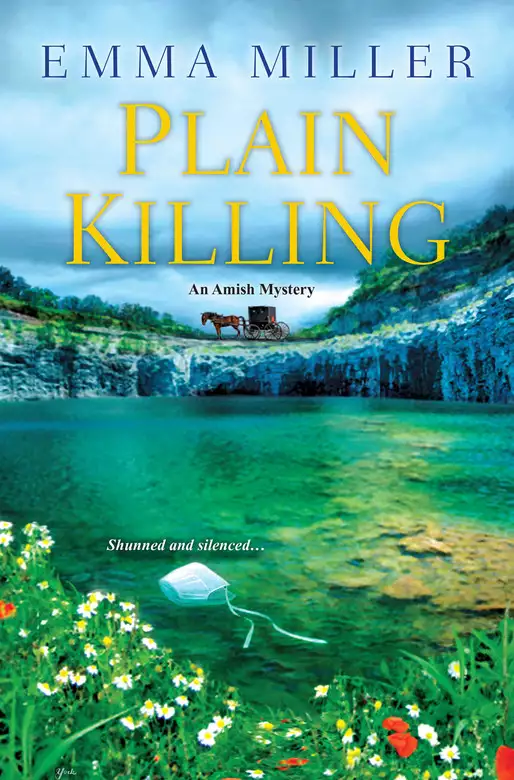

Synopsis

When the Amish community of Stone Mill, Pennsylvania, refuses to discuss a murder with the police, it's up to Rachel Mast to bridge the cultural gap and stop a killer from striking again. . . While swimming in a local quarry, Rachel and her cousin Mary Aaron discover the body of an Amish girl, fully clothed in her white bonnet, floating face down in the water. The drowned young woman, Beth Glick, had left Stone Mill and her Old Order Amish life a year ago, causing her to be shunned by her family and her people. But if Beth had joined the English world, why was she found dressed in Amish clothing and strangled? Rachel's boyfriend, police detective Evan Park, is getting nowhere with questioning Beth's family. He's also troubled over the fate of three other Amish girls who left Stone Mill in the last two years. As someone who gave up the Plain lifestyle herself then returned to operate a B&B, Rachel is able to use her ties to the community to learn more about the missing girls. But when her search eventually leads to the dark underbelly of the secular world, Rachel finds her own life in dire jeopardy. . . "Miller has written an exciting tale of mystery, love, and danger that will have readers turning the pages like crazy, wondering what the next big secret to be revealed will be and how Rachel will handle it." -- Booklist

Release date: December 20, 2014

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 290

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Plain Killing

Emma Miller

As Rachel Mast turned off the single-lane gravel road and onto the rutted logging tracks, the trees closed in around the minivan like a dark tunnel. It was one of those muggy August days that seemed too hot for central Pennsylvania, an afternoon when not a leaf stirred and even foxes and deer crept into the undergrowth seeking relief from the heat.

Rachel lowered the window and sucked in a deep breath of the still air, savoring the primal scents of old-growth conifers, and the stillness. Her companions, who’d been laughing and chattering in the back of the van, grew quiet and watched out the windows. Sophie, Rachel’s white bichon frise, ceased her excited whining to creep into Rachel’s lap and thrust a black nose out the open window.

Despite the heat, Rachel suppressed a shiver. A goose walked over my grave, she thought, and then chuckled at her own foolishness. She had an MBA from Wharton, and should have left superstition and old wives’ tales behind a long time ago, but there was something ominous about the stillness of this remote place today. She’d been feeling it since she turned off the main road onto the gravel road that wound around the mountain. “Almost there,” she called with forced gaiety. Glancing down at the console, she flipped the air-conditioning up to max. “That water is going to feel wonderful.”

“Ya,” her sister agreed. Sixteen-year-old Lettie was riding shotgun and had had to contend with Sophie’s nonsense for most of the ride.

“This was one of your better ideas,” their cousin Mary Aaron said from the bench seat in the middle of the van. “Good day for playing hooky.”

Rachel agreed. It had been a crazy week at her B&B. Three couples had reserved rooms for a long weekend and then canceled on Friday afternoon; then two decided to come anyway, a day later. Her computer had crashed, and she’d had to have the plumber out when one of her guests’ children flushed three washcloths and a bar of soap down the toilet. The clothes dryer wasn’t working right.... The list seemed endless. She couldn’t think of a better escape than to go to the quarry for a swim and a picnic with her friends.

And she hadn’t fled duty and responsibility by herself—Rachel and Mary Aaron had collected a gaggle of young Amish women, most of them relatives, for a few hours’ respite from their summer chores. Rachel was the only Englisher, the only nonmember of the Amish faith, among them, which meant she was the only one with a vehicle and a driver’s license, both considered by some in the Old Order Amish to be evils. Rachel, her license, and her vehicle were all guilty of abetting hardworking females who wanted to slip away from summer gardening and canning chores for an afternoon of illicit, if innocent, fun.

They made up a party of seven, eight if Sophie was counted. Too many bodies to cram into Rachel’s four-wheel-drive Jeep. Instead, she’d borrowed her next-door neighbor’s van, which provided room aplenty for passengers, towels, and coolers of food. An ice chest full of ripe peaches, local pears, and a huge watermelon made perfect picnic fare. It would all be washed down with lemonade Rachel’s housekeeper had made fresh in the kitchen of Stone Mill House that morning.

At last they made the final downhill curve and reached the mossy clearing beside the aggregate quarry that had filled with water years before. Rachel coasted to a stop near an ancient oak tree and shifted into park. “We’re here!”

Mary Aaron and Lettie slid out, and the rest followed. No one but Rachel had worn shoes, and soon modest dresses and prayer kapps were cast off, leaving the lot of them scandalously clad in cotton shifts and undergarments.

“Remember that it’s deep,” Rachel cautioned as they approached the steep edge. Crystal blue-green water glistened at her feet.

“Really deep,” Mary Aaron added, looking down. “More than a hundred feet. Dat says they mine until they can’t keep pumping water out, and then they just move on to dig another quarry.”

Lettie’s eyes widened as she peered over the edge. She was the youngest of the group, and this was her first time at the quarry. Her mam had let her go on the picnic only after delivering the severest of warnings to behave herself, to listen to Rachel, and not to go into the water. Her mam had also wagged a finger in her face and admonished her to not allow Rachel to drive the automobile at a reckless speed, which meant anything faster than a horse could trot.

As children, none of them had ever dared to swim here; parents were adamantly opposed, besides, more compelling to youthful imaginations, the quarry was rumored to be haunted. But most had ventured to this glen on summer afternoons every August since age fifteen, when Amish girls traditionally became considered young women.

The quarry was a secluded retreat where they could relax and set aside the strict rules of Old Order Amish dress and behavior for a few hours. Here, amid a tangle of old-growth hardwood, rhododendron thickets, and intertwined pine, spruce, and hemlock, the temperature—due to the flooded quarry—was at least ten degrees cooler than the rest of the valley.

Giggling, Lettie joined the other women as they carried blankets and coolers out of the van, all the while sharing family and valley news and bits of harmless gossip. Rachel helped spread the blankets on the thick moss and unpack the lunch baskets while Sophie ran in circles, chasing butterflies.

“Last one in is a rotten egg!” Mary Aaron dared and made a dash for the edge of the quarry.

Rachel, clad only in a T-shirt and panties, darted after her and dove deep into the shimmering depths. The icy water came as a shock, but she quickly adjusted, then reveled in the silky sensation of the blue-green water against her skin. Mary Aaron, always a strong swimmer, crossed in front of her before lazily rising to the surface. When Rachel came up for air, her cousin was floating on her back, her long sandy-blond hair drifting loose around her head and shoulders. Rachel dove under again and came up beneath her, flipping her over. Mary Aaron shrieked as she righted herself and returned the favor by splashing water in Rachel’s face. From the sheer-cut rim, Elsie, Mary Aaron’s nineteen-year-old sister, shrieked with laughter and plunged in to join them.

Soon everyone, including Lettie, was in the water. They remained there for a good half an hour before the water temperature began to temper their high spirits. Lettie was the first to admit that she was cold. “I’m freezing,” she said. “Can we eat?”

“Ya,” someone agreed. “I skipped lunch and I’m starved.”

“Me, too,” Mary Aaron said. Elsie nodded in agreement, and one by one, they climbed out, threw towels around their shoulders, and made their way to the blankets. Lettie passed around wedges of watermelon that her mother had contributed, and Rachel bit into a slice. It was so sweet and delicious that she closed her eyes and groaned with pleasure.

“It is goot, isn’t it?” Elsie agreed as she wiped at the juice running down her chin. “This was a great idea, Rachel.” She spoke in Deitsch, the old German dialect that the Amish used among themselves.

“Ya,” Lettie said, eager to add to the conversation. “Mam grows the biggest watermelons in the valley. She promised to tell me her secret when I get married.”

“Rachel must know,” Elsie teased.

“Ne.” Rachel shrugged. “Mam never did tell me, and now . . .” She spread her hands in a gesture of hopelessness. Gardening and cooking secrets or everyday greetings, it was always the same. Her mother never spoke directly to her. Her mother hadn’t spoken a word to her since, as a teenager, she’d abandoned her Amish upbringing, left home, and joined the Englisher world. Anything her mother had to say to Rachel was always passed to her through someone else. Rachel recognized it as the ultimate act of love. As awkward as it was, she knew her mother desperately wanted her to return to the safety of church and family.

“Lemonade?” Rachel poured an ice-filled paper cup nearly to the brim and offered it. “Ada made it this morning. Tart and cold.”

Sophie, who’d been on the blanket begging watermelon only a minute or two before, let out a piercing bark from a distance. Rachel glanced around. “Sophie! Where are you?” She couldn’t see the dog, but from the sound, she wasn’t on the path that led to the quarry from the clearing but in the underbrush. “Sophie, come here!” she repeated, knowing full well that the stubborn little dog would probably ignore her.

A miniature white poodle-looking dog of about fourteen pounds would not have been the dog of Rachel’s choice. Basically, she’d inherited Sophia Loren when a dear friend had gone to prison a few months earlier.

Sophie’s barking became a low growl.

“That dog.” Rachel rolled her eyes. “Only for George would I do this.” She stood and slipped her feet into zebra-striped flip-flops. Still clutching the towel around her, she plunged into the underbrush, pushing through the thick rhododendron. “Sophie! Come, girl! Come!”

“Don’t go in there!” Lettie called. “It might be a bear.”

“Not likely,” Rachel answered over her shoulder. “Not with all the noise we’ve been making.” Branches scratched her bare legs and arms and twined around her ankles. “With my luck, you’re trapped in a thicket of poison ivy,” she grumbled at the dog. She couldn’t imagine what had Sophie in such a fuss. Maybe a snake.

Sophie loved chasing snakes, although what she’d do if she ever caught one, Rachel had no idea. The thought that the bichon might have startled a rattler gave Rachel pause. “Sophie, come here!” As much of a pest as the dog could be, she had become a bit of a companion, and Rachel didn’t want anything bad to happen to her. “Sophie!”

The growls grew fiercer.

“Rae-Rae,” Mary Aaron called after Rachel. “Wait, I’m coming with you.”

“Me, too,” Lettie called. “I don’t want a bear to eat you.”

Rachel, now unable to see the girls in the clearing, forged ahead. Another ten feet and she pushed aside a thick evergreen bough to catch a glimpse of the white, fluffy bundle bounding up and down. Sophie’s plumed tail was at full sail. Her protests rose to a fevered pitch as she fiercely held some perceived enemy at bay with every ounce of will.

“Sophie! What have you—”

Rachel froze. Sophie had taken her stand only a few inches from the edge of the water. Rachel stared through the braches of a massive hemlock, a tree that had grown out over the water. Beneath the intertwined roof of foliage, nearly hidden from view, forty feet from where Rachel and the others had been swimming, a body floated.

Rachel’s mouth went dry. She blinked, hoping that what she’d glimpsed was only a figment of an overactive imagination. But when she dared to look again, the awful sight was all too real . . . and all too still.

Suspended facedown on the surface of the water was the body of a woman in full Amish dress, a white prayer kapp still on her head.

“Mary Aaron!” Rachel screamed as she took the few steps to the edge, threw off the towel, and plunged into the water. She had no idea who it was. None of those with her had been dressed in Sunday clothes.

Adrenaline pumped through her veins as she reached out. Grabbing a hold of the woman’s arm, Rachel seized a low-hanging hemlock bough and, vaguely aware of the crashing sounds of brush as help came, rolled the woman onto her back.

Her eyes were china blue. Not the blue of human eyes, but glass blue. Hard, cold, and lifeless.

For just an instant, in shock, Rachel released her grip on the body. The girl was dead. Her blue eyes were empty of life and beyond any earthly help. There was no question in Rachel’s mind. She looked up to see Mary Aaron, her mouth agape, staring down at her.

Mary Aaron’s face was nearly as white as the girl’s, and her pupils were dilated in fear. “Is she . . .” She didn’t say the word dead, maybe because speaking the worst out loud would make it real.

“My phone’s in the van,” Rachel managed, grabbing the girl’s sleeve. The girl’s prayer kapp began to sink and Rachel grabbed it, wrapping her fingers around the ties. “Call 9-1-1. Now. Run!”

Mary Aaron turned and pushed back into the underbrush as Lettie halted at the edge of the quarry. She took one look at the floating body and screamed, a high-pitched shriek of utter terror.

“Lettie!” Rachel called sharply. “Listen to me.” She got her arm under the woman’s armpit and looked up at her sister. The other girls were right behind Lettie now. They were crying, one nearly hysterical, but Rachel barely noticed them. Rachel kept her gaze focused on her sister, her voice steady. “Lettie, you’ll have to help me lift her over the edge. I can’t do it alone.”

Rachel was afraid to let go of the girl. The bottom was so far below. She could imagine the cold body slipping through her grasp, sinking down and down to rest on the bedrock of the quarry. This young woman, whoever she was, was someone’s daughter, possibly someone’s wife. No matter what her story was, she didn’t deserve this. No one did.

Then, it occurred to her the body wouldn’t sink. Not if she’d found it floating. But she still couldn’t let go. Wouldn’t.

“I can’t . . .” Shaking her head, Lettie backed away from the edge.

“You can do this,” Rachel insisted. “Mary Aaron has gone for help. I need you, Lettie. She can’t hurt you,” she added softly.

“She looks dead,” Lettie wailed. “Her skin is blue.”

She was right; the young woman’s skin was cyanotic. What was it her biology professor had said about drowning? Cold water made the skin of a victim dusky blue.

“It’s not for us to decide,” Rachel said calmly. It was what one did in emergencies. She knew the girl was dead, long dead, but it wasn’t up to her to determine that. What was up to her, at that moment, was to get this poor soul out of the water. “We can’t leave her here,” she reasoned aloud, to give herself courage as much as Lettie.

“Ya.” Features stark, lips drawn tight, Lettie hesitated, then dropped to her knees. She followed Rachel’s instructions without faltering: lift here, pull there. Lettie helped to get the woman onto solid ground, gave Rachel a hand up out of the water, then turned away into the bushes and vomited.

Rachel’s teeth began to chatter with cold, and one of the other girls dropped a towel around her shoulders. “She’s dead, isn’t she?” Elsie murmured, staring at the body gazing sightless at the sky.

“Yes,” Rachel answered. Gently, she pulled down the young woman’s tangled shift and skirt to cover her naked legs, and placed the sodden prayer kapp over the fair hair.

Lettie was weeping now. Softly. She joined the other girls, who stood in a semicircle.

They all stared at the dead girl at their feet.

Rachel supposed that she should have been horrified, even disgusted by the body, but all she felt was grief and compassion. She removed the towel from around her own shoulders, thinking that she would cover the victim’s face. It wasn’t until she knelt that she realized the dead girl looked familiar. At first, the young woman’s face had seemed more like a doll’s than a human’s, but now—“Elsie . . . is this one of the Glick girls?”

Her cousin gasped. “Ya. It looks like . . . it’s Beth.”

Lettie returned to Rachel’s side. “It is,” she whispered. “I know her. She came to our class at school and taught us how to crochet when I was in eighth grade.”

“Beth is the one who left almost two years ago,” Elsie added. “The Glick girl who was . . .”

“Die meinding,” Lettie whispered. “Shunned.” And then she gagged again.

Silence settled around them. Rachel pressed her lips together. Being shunned was the worst fate that could happen to a member of the Old Order Amish, a punishment reserved for extreme cases of misconduct. The thought was even more frightening than finding a dead body.

“Go back to the van,” she instructed quietly, running her hand down her sister’s arm. “All of you, go and dress. English men will be coming soon.”

“Oh.” Elsie covered her mouth with her hand. “Come, Lettie. Hurry.”

“Take Sophie, Lettie,” Rachel told her.

Lettie scooped up the little dog in her arms, then glanced back. She was eager to get away but obviously didn’t want to desert her sister. “You’ll be all right? Alone here?” she asked, hugging the dog to her.

“I’ll be fine,” Rachel assured her. “Someone should stay with her.”

Elsie, Lettie, and the others made themselves scarce, and oddly enough, once she was alone with Beth Glick, Rachel felt a calmness settle over her. She had covered the girl’s still face and staring eyes, but she couldn’t leave her side. “You’re not alone, Beth,” she murmured. Taking a slim, cold hand in hers, Rachel silently prayed for the soul of this unfortunate young woman.

Twigs snapped, and Rachel opened her eyes to see Mary Aaron hurrying toward her from the direction of the van. “They’re coming!” she called. “I called 9-1-1. They’re sending the paramedics.”

Rachel remained where she was, still holding Beth’s hand.

“Do you think you should touch her?” Mary Aaron asked as she came to stand beside her. “Will you be in trouble?”

“It’s Beth Glick.” Rachel pulled the towel away so that Mary Aaron could see the dead girl’s face.

“It is,” her cousin breathed.

Rachel placed Beth’s hand on the dead girl’s abdomen and arranged the other hand carefully so that one lay over the other. She wasn’t a large girl, and her pale hands were small and slender. “Elsie said Beth was shunned when she left the church.”

“Ya,” Mary Aaron agreed. “She had been baptized, so they had no choice.” She nibbled at her lower lip. “Her family never speaks of her.” Mary Aaron held out Rachel’s clothes. “Best you make yourself decent before the Englishers get here.”

Rachel nodded, surprised by how calm she was. Calm, except for her trembling hands. She went back to the edge of the quarry and rinsed her hands in the water. Then she began to dress.

“What was Beth doing here? Did she come to drown herself?” Mary Aaron had taken the time to put on her own dress and apron. Now she hastily twisted and pinned up her hair. She put on her white prayer kapp. “Was it a suicide?”

Rachel turned back to her cousin as she pulled her shorts over her wet panties. Her gaze dropped to the still form on the ground. She shook her head. “I don’t know. Why would she? If she’d come home—if she repented of her sins before the church elders—she’d have been forgiven and welcomed back into her family.”

“Ya, so what was she doing here?” Mary Aaron glanced around her nervously. “No one comes here alone. How would she even get here without a car or a buggy?”

“I don’t know.” Rachel pulled off her wet T-shirt and pulled a dry one on over her wet bra. “Did you bring my cell with you?”

Mary Aaron fished in her pocket and produced the phone. “Who are you calling?”

“Evan.” Rachel hit the numeral 1 on her speed dial. “I don’t want Lettie and the others to be here any longer than they have to.”

Evan and Rachel had had supper together and watched a movie at his house the previous night. He was on day shift this week. “I think he’s working traffic,” she said, more to herself than to Mary Aaron. His phone was ringing. He kept his personal cell with him. If he wasn’t busy, he’d pick up. Please pick up, Evan, she willed.

She felt responsible for bringing the girls today, and it would be her fault if they got into trouble. While spending time with her in frivolous pursuits wasn’t forbidden by most of the families, it certainly wasn’t encouraged. The Amish way was to remain apart from the world, and being in the middle of the discovery of a drowning victim, especially a shunned runaway, wasn’t where parents and church members wanted their young people.

The phone clicked in her ear.

“Rachel?”

She let out a sigh of relief. “Evan. I need you to come. Right away.”

“What’s wrong? Are you all right?”

“Ya. It isn’t me.” She quickly explained what had happened and where they were. “I need you to call Coyote Finch. I don’t think I can talk to her, or anyone just yet.” She took a breath. “I’ll forward you her cell number. Ask her if she can come right away. She can drive the Amish girls home. Maybe she can get here before things get crazy.”

“Not much chance of that. Not if you’ve already called it in.”

“Please, just call Coyote. Ask her to take Black Bear gravel road to the old lumber mill. It’s not far from here. I’ll send them through the woods. The girls can meet her there.”

“I don’t know, Rachel. If they’re witnesses, the investigating officer will want to question them.”

She turned away from Mary Aaron, who was looking anxious. “It will be all right. Mary Aaron is here with me. She’ll stay. Why would they need to talk to more than two of us? Evan, I—” She stopped and started again. “I think she’s been dead for a while. . . .” She trailed off.

“Hang in there. I’m coming.” He was calm, professional, caring. She knew she could count on him. “But if I can’t get hold of Coyote, you’re on your own with the girls.”

“She’ll pick up. Afternoons, her husband puts the baby down for a nap. She’ll be at her pottery wheel.”

“Be there as quick as I can,” he promised.

Rachel ended the call, forwarded the number to him, and glanced at Mary Aaron. “Is that all right? Will you stay?”

She offered a wan smile. “What are best friends for?”

Uncle Aaron would not be pleased, and neither would Rachel’s aunt, but they were used to Mary Aaron’s objectionable dealings with Rachel. Mary Aaron hadn’t been baptized yet, so she was still permitted some leeway in her behavior. When Evan was there, the two of them could at least shield Mary Aaron from the Englishers who would arrive in their emergency vehicles. And they could make certain no one photographed her, if the press showed up.

“It was the only thing I could think of,” Rachel said. “Asking Coyote to come for the girls.”

“Ya, it’s best.” Mary Aaron motioned toward the picnic site. “Elsie used to go with our brother when he bow-hunted up here. She can show them the way to the abandoned lumber mill.”

The wail of a siren came from the mountain road. “Hurry,” Rachel urged. “Tell Lettie to take Sophie for me. Get the girls into the woods before they get here. I’ll walk to the road so I can show the paramedics where Beth is.”

“It seems a shame, indecent almost—strange men taking her away.”

Rachel sighed. “I know, but it’s the way the authorities work.”

“Foolishness. Better to call the bishop and Beth’s family to carry her home. She needs prayers, not doctors.”

Rachel agreed with her, but knew she would be wasting her breath trying to justify Englisher regulations. Mary Aaron knew more than most about how the English world worked, or at least how it worked in the valley. Her family and their Amish community, however, may as well have been living in the nineteenth century. They were practical people of faith, and much of what the English did was beyond their ability to comprehend.

With a last look at Beth, Rachel followed her cousin back to where the other girls waited. As she expected, they were all eager to be away from that place. Elsie was sensible. Rachel could count on her to guide Lettie and the other three to the pickup spot. And Rachel knew that Coyote would be there to get them and see them home safely. She was a new friend, but the kind Rachel could count on.

Evan was only five minutes behind the first paramedics from Stone Mill’s volunteer fire company. Rachel watched gratefully as he pulled his patrol car into the glade and got out of the vehicle. As always, he looked bigger to her in his state police trooper’s uniform than he did as a civilian.

“You came.”

He put out his arms and she went into them. She closed her eyes as he hugged her and brushed a kiss on the crown of her head.

“Did you think I wouldn’t?” He gave her a final hug and they stepped apart. “I’m really sorry that you had to be the one to find her.” He brushed dust off the fabric of his pants. “Road construction,” he explained. “I’ve been eating dirt all a. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...