- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

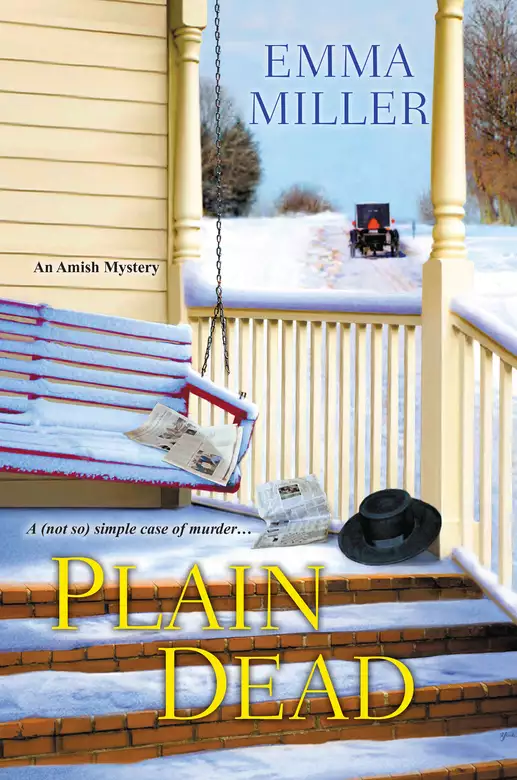

Synopsis

When a newspaperman is murdered in the Amish community of Stone Mill, Pennsylvania, Rachel Mast digs up the dirt to find out who wanted to bury the lead… Although she left her Old Order Amish ways in her youth, Rachel discovered corporate life in the English world to be complicated and unfulfilling. Having returned to Stone Mill, she’s happy to be running her own B&B. But she’s also learning—in more ways than one—that the past is not always so easily left behind. After local newspaperman Bill Billingsly is found gagged and tied to his front porch, left to freeze overnight in a snowstorm, Detective Evan Parks—Rachel’s beau—uncovers a file of scandalous information Billingsly intended to publish, including a record of Rachel pleading no contest to charges of corporate misconduct. Though Evan is certain of her innocence, it’s up to Rachel to find the real killer. A closer examination of the victim’s unpublished report leads Rachel to believe the Amish community is far from sinless. But if she’s not careful her obituary might be the next to appear in print…

Release date: December 29, 2015

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 274

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Plain Dead

Emma Miller

“Careful. Watch your step,” Evan cautioned. “The snowplows did a pretty good job of cleaning up after the last snow, but it’s still slippery in spots.”

“I can’t believe it! People came out for the frolic.” Rachel could hardly contain her excitement. “I hoped they would, but with the storm coming in, I was afraid they might not.”

“I’ll admit I never expected to see this many visitors.” Evan grinned down at her. “I should have had more faith in you, Rache.”

“It was a long shot,” she admitted. “Most towns only hold festivals in the summer for a reason.”

Hosting a big festival had been a risky proposition for the town, and much of her reputation rested on the outcome. Like so many rural communities, Stone Mill desperately needed any kind of financial boost it could get after years of national economic downturn. Rachel had been born here, which should have made her trustworthy. But she’d left her Amish upbringing and stayed away for fifteen years, going to college, then joining the corporate business world, which thinned the ties and made her suspect. Stone Mill was an isolated mountain community that held to old ways, familiar faces, and tried-and-true solutions.

Even after some of her previous successes, like the fair they held in the town square on Saturdays in the summer months, it had taken a lot of persuasion to convince the valley residents and business owners that hosting a weeklong craft show and celebration midwinter could be a success. Had the project flopped, she’d have had a difficult time getting people to listen to her next harebrained idea. Luckily, it didn’t look to be a flop.

January was usually a slow season for her B&B, but Stone Mill House was booked all week with every room filled. The previous night, she’d seen that Wagler’s Grocery, The George, Junior’s Diner, and Russell’s Hardware and Emporium were all crowded with out-of-towners. So, despite minor glitches in the festivities, the below-normal temperatures, and the threat of a snowstorm, the festival seemed headed in the right direction.

“Rachel! Evan!” A young woman dressed all in black, with both one eyebrow and one nostril pierced, shifted a box of books to one hip and waved. “Wait until you see our table! It looks awesome!”

Rachel waved back. “Is George here?” Ell owned the town’s bookstore, but it had once belonged to her Uncle George.

“Are you kidding? I couldn’t keep him away,” Ell called back.

“Need help with that box?” Evan asked.

“Got it!” Ell shifted the weight to both arms again. “Rachel, don’t forget that you promised to help with story time for the kids. I need you at noon for an hour-long shift.”

“I’ll be there.” Rachel returned her attention to Evan. “Be sure to keep an eye on Mary Aaron’s strawberry jam, right? Because her mother insisted they were short one jar after the Christmas bazaar.”

Evan was wearing his state police winter uniform, which made him appear taller, broader of shoulder, and even more imposing than normal. He’d recently been promoted to detective but had volunteered to serve as security for the Winter Frolic’s biggest day, free of charge. Rachel didn’t really think that security was needed to guard the tables of whoopie pies and hand-crocheted hot mitts, but she’d learned by trial and error that city folks, visiting for the day, felt more at ease with a tall trooper keeping an eye on things.

“Just doing my civic duty,” he replied with a wink. “Serve and protect.”

She laughed and gave his arm a squeeze. For two years Evan had pursued her, and she’d finally agreed to marry him when he’d proposed again on New Year’s Day. Somehow, making that decision had changed things between them. In a good way. “Would you mind giving a hand with traffic control, first?” she asked sweetly. “Before you start guarding the jam?”

As if on cue, brakes squealed and a car horn sounded from the street. “I’m on it,” he said. “See you later?”

“Absolutely,” she agreed. “I hope you brought a change of clothes. You promised me a sleigh ride, and I’m not letting you out of it. I’ll get tickets.”

It hadn’t taken much arm-twisting to get her father to agree to let her brother Moses polish up the two-horse sleigh and deck the team with bells so that he could offer old-fashioned Amish sleigh rides during the festival. As she’d suspected, there’d been so much interest that Moses and his wife, Ruth, were taking reservations, and they were attempting to locate a second sleigh and driver.

“Late lunch first and then the sleigh ride,” Evan bargained. “You know how I feel about horses.” He squeezed her gloved hand. “You’re wearing it, aren’t you?”

She laughed. “Of course I’m wearing it.” When she’d finally accepted Evan’s marriage proposal, he’d slipped an antique diamond ring on her finger. “I haven’t had it off since you gave it to me.”

“Good. This will be a chance to show it to everybody and let the whole town know you’re taken.”

Inwardly, Rachel grimaced. Had she had her way, there wouldn’t have been an engagement ring. The Amish didn’t believe in jewelry, not even wedding rings. And while she was no longer Amish, she knew her family, especially her parents, wouldn’t approve. Rings were considered worldly, and the Amish were a people set apart from the English world. Although she’d left the faith when she was seventeen, some steps were still hard for her. If she’d had her druthers, she would have settled for a simple wedding band and skipped the diamond altogether, but Evan didn’t understand. He’d been so pleased with himself that she didn’t have the heart to refuse to wear the engagement ring. And it was beautiful, and she loved him for being him. She sighed. Maybe the English world had changed her more than she wanted to admit. But not enough that she felt comfortable flaunting an expensive diamond in front of her Plain friends and neighbors.

As Rachel trudged across the parking lot to the sidewalk, she heard her name being called. She looked up to see an Amish couple standing halfway between the entrance to the school gym and the buggy parking. Since almost all of the Amish women dressed similarly in black dress bonnets, capes, and coats, it was often difficult to tell them apart from a distance, but there was no mistaking Naamah, with her husband, Bishop Abner. He was small and thin; she outweighed him by at least fifty pounds and stood a head taller. The smiling bishop made his way along the sidewalks, weighed down with split-oak baskets of canned goods, presumably to sell at the Plain Pickle and Jam stand her parents’ Amish church community was sponsoring.

“Rachel!” Naamah called excitedly. “So many Englishers coming to our frolic. Wunderbaar.”

Naamah gave a quick hug to a small Amish woman going in the opposite direction, then hurried toward Rachel, her husband trailing three steps behind.

Swooping down on Rachel, Naamah enveloped her in an enthusiastic bear hug, and Rachel was instantly engulfed in the familiar scents of her childhood—damp wool, starch, and dried lavender. “So happy we are that the snow doesn’t drive away our visitors,” Naamah bubbled. She had a merry voice and eyes that shone with the joy of life. “Lots of people here, it looks.”

“Yes,” Rachel agreed. “I was afraid the weather would keep tourists away. The road over the mountain into the valley can get slippery, but they must be braver than I thought.” She glanced back toward the woman Naamah had embraced. The smaller figure had turned back toward the buggies. “Was that Annie Herschberger?”

“Ya, poor Annie,” the bishop confirmed. “A difficult time for her and her family.”

Annie was a sister-in-law to Alvin and Verna Herschberger, the young couple who made the delicious goat cheeses that Rachel sold in her gift shop. She was also a friend of Rachel’s Aunt Hannah, but Rachel didn’t know her well.

She watched as Annie walked to one of the buggies and climbed inside.

“Is she leaving already?” Rachel asked.

“Just going back to fetch a pumpkin cake for the bake sale,” Naamah said. “She thought either my husband, Joab, or our Sammy had carried it into the school with her raisin bread and krum kuchen, but they can’t find the cake.”

“I wondered where Sammy was,” Rachel remarked. A few months ago, Naamah’s eighteen-year-old nephew Sammy Zook had come to stay with them. He was a big boy, strong and good-natured, but slow in mind and body. Naamah said that Sammy was full of fanciful tales and couldn’t be trusted to give a straight answer if his life depended on it, but as far as Rachel could see, his presence was a great help around the farm to Naamah and Abner. Childless, the two had to perform alone the many tasks living simply demanded, such as chopping wood, building fences, milking and caring for the animals. It seemed a good solution for all three of them as the bishop was growing no younger and Sammy was obviously thriving under his aunt and uncle’s loving care.

“Ach, Rachel.” Naamah shook her head sadly. “Poor Annie said she didn’t want to come today, to maybe have people staring at them and whispering behind their back, but Abner insisted they shouldn’t hide. If there was fault, it was Joab’s, not hers. She has no reason to feel shame, and gossip soon grows cold when idle minds turn to new mischief.”

“I agree wholeheartedly,” Rachel said.

The bishop turned to Rachel and asked, in a low voice, “Did you have a chance to talk to Bill Billingsly yet?”

She shook her head. “He’s been out of the office all week, supposedly. I’ve called three times and I’ve left messages. I think he’s hiding because he’s afraid of me.”

“I’m opposed to violence, of course, but it might be that he should be afraid of me as well.” Bishop Abner stroked his long beard. “I’ve been praying hard on the matter. Trying to temper my anger. I just can’t imagine why that newspaperman would want to hurt good people like Annie and Joab.”

“Ya, they are both good people,” Rachel agreed. “And we need their contributions to the community. Mary Aaron said they were talking about selling the dairy farm and moving out to Wisconsin.”

“What a terrible loss that would be.” The bishop frowned for a moment but then turned back to her, forcing a smile. “Enough talk of the newspaperman. He’s not worth our time to fret over. Congratulations on such a fine turnout. Clever, this idea of yours, Rachel. To bring tourists to our town in the cold of winter.” He looked at his wife with obvious affection. “But then, not even Englishers can resist my Naamah’s rhubarb jam.”

“If any jars are left over next weekend, just drop them by the inn,” Rachel said. “You know what a big seller they are in the gift shop. I sold seventeen jars of Naamah’s chowchow in December.”

“Maybe I should give up raising sheep and learn to make chowchow,” he replied. “I would, if I could talk my good wife into giving up her secret recipes.”

“No, because if I tell you, you’ll hand them out to anyone who asks,” Naamah retorted. “I know you. You’re a pushover.” She laughed again, her round cheeks and the tip of her snub of a nose glowing as red in the icy air as a pickled egg.

“How can I help it?” he teased. “Doesn’t the good book tell us to be kind to our neighbors?”

“Ya, but it says nothing about giving away my grandmother’s recipe for tomato mincemeat or chowchow.” Naamah’s brown eyes sparkled with good humor beneath the rim of her black dress bonnet. “At the last school fair, I took six jars and Mathiah’s Gertie and her sister Agnes brought a dozen exactly the same. They offered theirs cheaper and sold out before me.”

Bishop Abner’s scraggly reddish-gray beard bobbed up and down as he chuckled again. “And all for the same good cause.” He shifted the heavy baskets and rested one in the snow. “Money for the schoolhouse addition, so what was the harm?”

“None, I suppose,” Naamah allowed. “But my gross-mama would not approve.”

“Let’s get inside before we all freeze,” Rachel suggested. “Those baskets must weigh a ton.”

“I told him I could carry some,” Naamah fussed, “but he wouldn’t hear of it. If the bishop had his way, I’d be spoiled rotten.”

“And who should I do it for if not my own wife?” He scooped up the basket of pickles and jam and followed Naamah toward the entrance to the school gymnasium.

Rachel trailed after them, thinking what a positive force Abner Chupp was for the community. He was bishop for her family’s church and as dear to Rachel as his wife was. He might be diminutive in stature, but he loomed large in the valley both as an example of how an Amish man should live and as a kind and wise religious elder.

Some, even members of her own family, might openly show their disapproval of her choice to leave the faith and become part of the English world, but Bishop Abner never had. All he’d ever offered was friendship, understanding, and an open invitation to return to the Amish way of life. As for Naamah, Rachel adored her. Despite the good-humored bickering that went on between her and her husband, Rachel knew that the two were devoted to each other and never really disagreed.

Rachel paused to greet a few other acquaintances and then stepped through the double doors into the gym. Although she’d been there early that morning, she was amazed by how fantastic the place looked with the addition of big glittery white snowflakes hanging from the ceiling, and twinkle lights looped in all the doorways and overhead. Booths offering everything from hand-woven willow baskets to baked goods, wooden toys, antiques, hand-stitched quilts, and forged iron trivets and fire irons lined the walls. Ell’s bookstore, The George, filled two spaces with books for sale, with a third serving hot tea and scones in a reading area and a fourth, carpeted with rugs, designated as a children’s story area. There was a double booth offering reproduction colonial- and mission-style furniture and a Mennonite couple’s display of one-of-a-kind lighting fixtures.

Rachel spied her friend Coyote’s pottery stall and walked over to see how things were going for her. Coyote was the local potter, a talented artist who had transplanted her family from California. Coyote and her husband, Blade, were just the kind of entrepreneurs Rachel hoped to draw to Stone Mill. Rachel didn’t see Coyote, but Blade, a rough-featured man with a long ponytail, a scraggly beard, and full sleeves of tattoos, was behind the counter, the newest addition to their family tied to his chest with a colorful baby sling. A small boy in a wheelchair sat beside him, scrolling through an iPad.

Blade glanced up, saw her coming toward him, and grinned. “Rachel. Coyote was looking for you earlier, but she just ran out to the car. This one”—he glanced meaningfully down at the sleeping infant—“just had a major explosion, and I left the diaper bag in the van.”

“I’ll be around for a while, so I’ll catch up with her. Hi, Remi,” Rachel said to the small boy. He had a round face; silky black hair cut straight across his forehead; large, dark, intelligent eyes; and skin the exact shade of English toffee. “Are you reading anything good today?”

“The Giving Tree, but I read it before. I know how it ends.” Remi had an endearing lisp.

“I imagine Ell has some wonderful books over there. Maybe we can find you something you haven’t read yet.”

“Just what his mama said,” Blade agreed. “Although it’s hard to keep him in books. He’s reading everything he can get his hands on.”

Rachel suspected that Remi’s IQ, as yet to be formally tested, would surprise even his parents. Not old enough to attend kindergarten yet, Remi had already been reading chapter books for more than a year. “At least you’ll never be bored.”

Intense pewter-gray eyes lit with pleasure. “Coyote says that, too. Whatever may happen, our kids are our treasure.”

Rachel nodded. For all his scary tattoos, her friend’s husband was a gentle soul and a model family man always willing to help his wife or his neighbors. She knew Blade had spent four nights that week erecting booths for the festival as well as shoveling fresh snow and ice off the high school sidewalks. “I saw your booth was drawing a lot of interest from visitors this morning. How are sales?”

“Great, so far,” Blade answered. “I think Coyote wants me to bring over some more of those blue mugs and the cream pitchers this afternoon. She sold one of the sinks already, the one with the brown swirl.”

“It was beautiful. She’s going to make one for me for that little half bath I’m making out of a downstairs closet.” She smiled at Remi. “Tell your mama I’ll stop back by.” He nodded and Rachel moved on.

Coyote’s pottery booth stood beside a larger display of oils and watercolors featuring work by local artists past and present. Beyond that were candle vendors and stands displaying braid rugs and traditional painted floor coverings. Rachel’s own booth was given over to photos and text relating the history of the Stone Mill valley from the seventeenth century up to the present, including a case featuring a local collector’s stone spear points, Native American pottery, and models of the type of homes and farming methods used by First Peoples. A friend and neighbor, Hulda Schenfeld, had volunteered to host the booth for a few hours today. It was Hulda who’d insisted that the display include before-and-after restoration photos of Stone Mill House and magnets with the phone number of the B&B listed. Hulda, in her nineties, remained a savvy businesswoman, and Rachel knew she had a lot to learn from her.

More than half of the vendors were Amish. One entire wall of the gymnasium was given over to foodstuffs, with residents offering local goat cheese, honey, apple cider, pickles and relishes, and all kinds of jams and jellies. There were folks selling homemade leather goods, handmade brooms, and wooden rockers and baby cradles. There were also craft projects and face painting for children, a petting zoo in one of the outer garages, and winter activities for all ages, including the horse-drawn sleigh rides, an ice sculpture contest, snowman-building competitions, and Rachel’s favorite, a huge ice rink. Visitors could rent skates, glide on the flooded and frozen man-made pond, and warm up with hot chocolate brewed over an open fire.

Rachel was approaching a display of local cheeses when she felt sharp claws on her ankle and heard a familiar yipping. She glanced down to see a small white bichon frise hopping up and down. “Sophie, no,” she said. Sophie ignored her as usual and kept jumping and yipping. Rachel knelt and scooped her up, trying to avoid wet kisses as she glanced around for the dog’s owner.

“Sophie, you bad girl. Sorry, Rachel. She slipped off her leash.” Leaning heavily on a polished walnut cane with a fox-head handle, George O’Day made his way toward her. “Didn’t I tell you that you can’t do that?” he reasoned with the little dog. “It isn’t safe. You could be trampled in this crowd.” He gathered Sophie into his arms and held her against his chest while Rachel slipped the collar around the bichon’s neck and then lowered her to the floor. Immediately, Sophie began hopping and barking again, but the leash held her fast.

“I doubt anyone would trample her,” Rachel said. “I’d say the visitors are more in danger of having Sophie trample them.”

“She wouldn’t hurt a fly,” George defended. “She’s just happy to see you, aren’t you, Sophie? I think she misses you.”

“It was you she missed, George. She was homesick the whole time you were gone.” Rachel looked into his puffy, pale face. His white dress shirt, brown bow tie, and brown cardigan sweater were a little at odds with the colorful Scandinavian knit hat that covered his bald head, but his eyes were clear and alert. “Are you sure this isn’t too much for you?”

“I’m fine,” he said, smiling. “Wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

“Still, you should take care of yourself,” Rachel warned. “Give yourself time to heal.” George, a convicted felon recently released from prison, was five weeks out of brain surgery, surgery that few of his physicians had expected him to survive. But he’d beaten the odds and, with the removal of a tumor, seemed to be well on the road to recovery.

“Have you seen Billingsly?” she asked George. She knew he’d been avoiding her since the early-week edition of his paper had come out, but he couldn’t hide forever.

“Bill? Not in the last hour.” George shook his head. “Sophie doesn’t like him, so he stays clear of her. Last time he came into the bookstore, she tried to take a nip out of his ankle. He threatened to sue, but I told him to go ahead and try. Me, an old man with a brain tumor who taught most of the residents of this county. Him, an outsider slandering wholesome Amish families and good townsfolk. Give me a jury of our peers and we’ll see how it goes.”

Rachel reached out to scratch under the little bichon’s chin. “They say dogs are excellent judges of character.”

“There you go.” George gestured. “If you had been earlier, you would have tried to take a bite out of him.”

“Why? What was he doing?”

George shrugged. “The usual. Trying to take pictures of some of the Amish kids in the children’s play area. Your cousin Mary Aaron spied him and alerted their mothers. Lickety-split, before you know it, there were a dozen riled Amish mothers surrounding the children, their backs to Billingsly. If he took a picture, it was of a wall of black bonnets and capes. Then, when he backed off, the Amish women started shaking their fingers at him and fussing at him in Deitsch until he made a beeline for the door. Bill’s ears were burning, I can tell you that. I doubt if he understands much Amish, but your sister-in-law Miriam called him a thickheaded English mule. Even if Bill didn’t get the exact translation, he got the message.”

“You know, I’ve had it with him,” Rachel said, her temper rising. “He’s lived he. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...