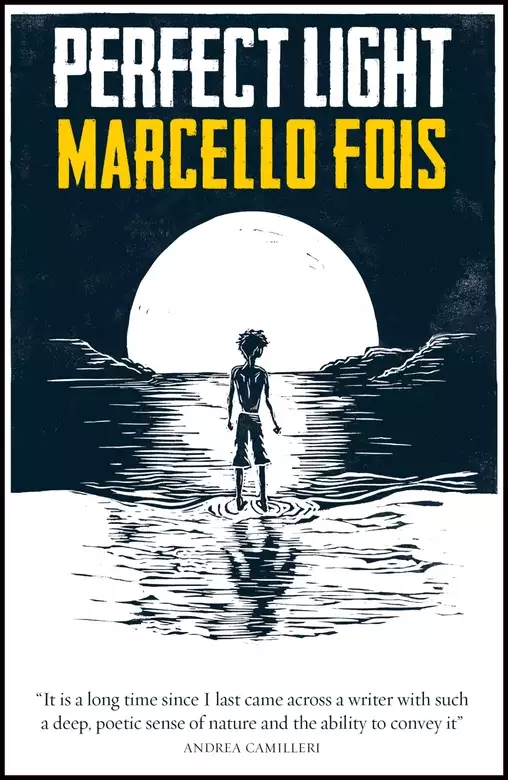

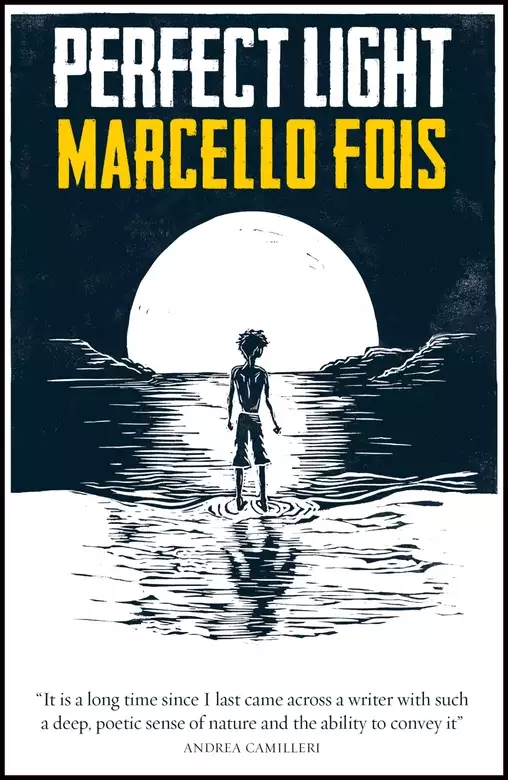

Perfect Light

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Cristian is enterprising and determined. Maddalena is tenacious and quite able to imagine - and defend - her own future.

Cristian and Maddalena have always known each other, and if fate had not gone awry they might already be married. But between them, exactly in the middle, there is Domenico: Cristian's childhood friend who has grown up alongside him like a brother. And when Cristian succumbs to the fate of the Chironis - that curse of illnesses, murders and suicides that has blighted his family over the years - it is Domenico that Maddalena marries.

Taking his trilogy of the Chironi family up to the present day, Marcello Fois has woven a delicately detailed story, full of dormant passions, plot twists, betrayals and reconciliations. The epic scope and the dramatic tension of his writing means that while his trilogy might be the story of one family on a tiny island, it has a universality, a humanity and a power to speak to anyone of us.

Release date: January 9, 2020

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Perfect Light

Marcello Fois

The morning before, carrying a small suitcase, she had caught the ferry from Porto Torres to Genoa. That had meant getting up before dawn to reach the port in a hired car, then waiting all day to board the ship in the evening. Alarmingly, during those dead hours, she had even been tempted to give up. But she was a woman who had been forced to learn tenacity. She had known far worse periods of waiting during the course of her forty years. After the ferry she had caught a train from Genoa to Torino, an unprecedented experience for a woman who had never travelled anywhere by train in her native Barbagia. Then finally, by means of a local train from Torino and a coach, she had reached Gozzano, a place whose address she had learned to write down perfectly and which turned out to be quite a small building of fairly recent construction. To be honest, it had the atmosphere of a clinic. Or a school for priests. Or a seminary, which is what it was. In fact, the whole village seemed to hint at honest sobriety. A cold compassion perfectly in tune with the freezing weather gripping it. January was showing its fangs, and Maddalena Pes realised she had not dressed warmly enough. Sighing, she pressed the doorbell a couple of times. A lock snapped back and the front door opened.

The deserted corridor inside was dominated by the smell of the kind of floor-wax dear to ecclesiastical housekeepers. Its walls featured a few naively creepy images, a few posters advertising missions, and shelves decorated with little vases and doilies in the childish style sometimes favoured by nuns and elderly women when chance throws them into contact with all-male communities.

Taking a few steps forward, Maddalena passed one closed door on her right, then another. Before she could reach the third it opened, and a tall man dressed in grey came out. He looked no older than twenty-five, and when he saw her he gave a smile of enthusiasm seemingly unrelated to her presence.

“You must be Luigi Ippolito’s mother,” he said. “We’ve been expecting you.” Maddalena nodded. “Let me,” he continued, reaching with nervous politeness for her suitcase. Maddalena did not resist; she was tired and cold, even though the building was warm inside. “Luigi Ippolito is busy at the moment with the boys, but he’ll be here in a moment.” The young man had the condescending good manners of someone impatient to get back to whatever he had been doing before he was interrupted.

Maddalena forced a smile. The man did not respond, but led her into a modest room furnished with bulging brown leather armchairs, their back rests decorated at shoulder height with coarse pieces of multicoloured cloth crocheted from woollen scraps. He put her suitcase down on a chair and straightened up almost as if expecting a tip. Glancing at his wristwatch, he repeated, “He’ll be here in a moment,” then stood to attention with his hands crossed over his bottom as if to make clear that he knew it was his duty to escort and guard her until her son arrived.

“We’ve heard what happened,” he murmured as they waited. “Such things are not good, but the Lord helps us to get over them.”

Maddalena studied him carefully for the first ime: he was a very tall youth, well built and well groomed. “And what have you heard?” she asked sharply.

The man stammered a reply: “Luigi Ippolito has told us about his father . . . yes indeed . . . about the accident . . .”

“Are you a priest?”

“A novice. Still some way to go . . . If Christ accepts me, I’ll be a priest soon. People think we decide these things for ourselves, but the decision is entirely His.”

“You mean Christ’s?” Maddalena added, to be quite sure she had not misunderstood.

“I mean Christ’s,” the novice confirmed.

This was followed by a silence filled with noises. It was only then that Maddalena noticed that the room was just what the late-lamented Marianna Chironi might have called an “eating area” rather than a drawing room, kitchen, studio or antechamber. In fact, it was a room that only existed in terms of what it was not. Where Maddalena came from most things now thought of as modern had come into houses via the “eating area”, which was the main reason why old and once precious pieces of furniture had been sold off cheaply or chopped up for firewood. Such “eating areas” would feature an ancient television set that was never turned on, and be decorated with scraps of cloth similar to those on the armchairs in this room, though this one was smaller, and also contained a little vase with a couple of artificial carnations.

After waiting for several minutes during which nothing happened, Maddalena decided to sit down. She chose a plain chair rather than one of the armchairs. The man hinted at a smile, as if approving of her decision to be comfortable.

“So Luigi Ippolito has told you about the accident,” Maddalena said unexpectedly.

Shot out like this, her statement was almost an accusation. “It’s impossible not to realise how much it has affected him; there are times when no words are needed,” the novice mumbled.

“I can well believe it.” Maddalena allowed herself a touch of sarcasm.

“Luigi Ippolito has done a lot of praying,” the young man assured her.

“Of course, that’s only to be expected. I mean, that’s what you are here for, isn’t it?”

The novice stiffened. “Yes, exactly. Here we pray,” he answered as if avoiding compliments in order to respond to a challenge. “Sometimes we also pray for those who do not pray themselves,” he added.

Maddalena looked at his perfectly shaved face and impeccably cut hair, his autumn-green eyes, high cheekbones and slender neck. “You’re a good-looking man,” she said aloud, not quite able to hide the fact that what she meant was “too handsome to restrict yourself to a life of chastity”. Just as the clients of some prostitutes can’t help saying “you’re too beautiful to live this kind of life”.

The man opened his arms as if to stress that he had implied nothing of the kind, and changed the subject. “Luigi Ippolito should not be much longer.”

Nor was he. The boy arrived slightly out of breath and took a step or two towards his mother without indicating in any way that he expected her to embrace or hug him. She took his face in her hands, pulling him against her breast and kissing him on the forehead. The novice hurried out so as to leave them alone.

“So you’ve met Alessandro,” her son said, using this as a pretext to disengage himself from his mother’s arms.

Maddalena made a non-committal gesture. “You’re looking well,” she observed with ill-concealed disappointment, as if she had expected to find him injured or emaciated.

“I am well, in fact.”

Maddalena reflected that apart from the fact that he was the shorter by a few centimetres, he could have passed for a clone of the novice whom she now knew was called Alessandro.

“With your hair cut and a little extra weight, you’re certainly looking well,” she confirmed.

Her son nodded.

The ugly room, the multicoloured doilies, the calendars with pictures of dogs and cats, the armchairs like plump Phoenician beauties, and even the little vase with its plastic carnations, seemed to be spying on them.

“They all say you look as if you’re my sister,” Luigi Ippolito said eventually to break the silence.

“How do you mean ‘They all say’?” Maddalena was surprised to have been noticed, since she had not seen anyone, apart from the young man who had received her.

“All the others,” her son explained, as if that were an adequate answer.

“I’ve seen no-one.” A touch of irritation was creeping into Maddalena’s voice. She did not like situations where she was not in complete control.

“But they’ve seen you,” Luigi Ippolito concluded as though that was the only thing that needed to be said.

“Must we stay in here?” Maddalena asked. “I’d like to see your room. Where you live, I mean.”

What she meant was quite clear to Luigi Ippolito. “It’s nothing much,” he said evasively.

“But all the same,” she insisted drily, as she always did when she felt a need to remind her son that although he may well have been sent into the world deliberately to antagonise her, she had no intention of accepting this.

“I have a single bed, a desk, and a wardrobe,” he said, doing his best to make the list sound banal and tedious. “What do you want to see?”

“A single bed, a desk, and a wardrobe,” she repeated pedantically, trying to echo the exact tone of his voice.

He changed the subject abruptly. “I thought I’d take you out to supper.”

“Is that allowed?” Her mockery was palpable.

Luigi Ippolito refused to be drawn. “We can go out.”

“But you won’t show me your room. What’s this room we’re in now, anyway; a special place for interviewing visitors?” She swept her arm round as if to include the whole of it.

“I’ve never thought about that,” Luigi Ippolito admitted, also looking around. “I’ve hardly ever been in here before, to tell you the truth.”

“You mean you’ve not had many visitors.”

“What I said is exactly what I wanted to say, Mamma.” Judging by the way Luigi Ippolito pursed his lips, Maddalena’s own approach of pre-empting people before backing off was beginning to bear fruit. It was something he had done ever since he had been small, pursing his lips like that when he wanted to stay in control. Every time he had to deal with being denied or criticised. Every time anything was not going the way he wanted. He had been a difficult child.

“I’m not stayjng in this room,” Maddalena said. “You were going to take me out to supper, remember?”

“Yes.” Luigi Ippolito’s expression had the same immobility as the ferocious January weather biting the mountains to pieces almost as if they had been nothing more substantial than slivers of chocolate.

“I must stop by the guest house first . . .” she said. It had grown dark outside. An inscrutable gloom, foreign and hostile. “I feel I’m being a burden to you,” she confided, after a short pause.

Luigi Ippolito came up with a smile that made things worse rather than better, but remained silent.

“Have you nothing to say?” Maddalena asked, as if longing for him to contradict her.

“What is there to say? As Babbo used to put it: ‘a paragulas maccas uricras surdas’.” Luigi Ippolito’s Sardinian was carefully nit-picking, as if to tease.

“You’ve always been the best at ‘deaf ears’, but I win when it comes to ‘silly words’.”

“I didn’t mean that seriously,” Luigi Ippolito felt he had been too harsh. “Can’t you take a joke anymore?”

“No, no, for goodness sake . . .” Maddalena buttoned up her coat ready to go out.

Luigi Ippolito preceded her into the passage, and just before reaching the front door grabbed a padded blue jacket from a coat-hanger.

The cold took no more than a few seconds to swallow them up. And it wasn’t six o’clock yet. When they passed the guest house, Maddalena dropped her suitcase off and the landlady lent her a woollen scarf.

*

“Are you hungry?” Luigi Ippolito asked when they were finally sitting opposite one another at a table for two at the trattoria which, perhaps not entirely by chance, had been called Osteria del Prete or “the Priest’s Inn”. He said in an encouraging voice, “The food they do here is simple but good. What would you like?”

Maddalena tried not to show that she never liked eating out. She was a woman who had always considered eating on a par with washing, something extremely personal. Even so she could not help smiling when she remembered the many times her husband had tried to take her out to lunch or dinner. “No-one but you could ever have got me into a restaurant.”

“Restaurant’s a big word. But the food’s excellent and the prices are reasonable.”

“And the prices are?” She couldn’t resist teasing him a bit.

“Reasonable.” It took him a moment to realise his mother was making fun of him.

They both laughed. Like the time many years before when they had played a trick on his grandfather Giuseppe, whom everyone called Peppino. Luigi Ippolito had had to pretend he’d been abandoned at home on his own . . . How they’d laughed to see how fast the old man ran to his grandson despite the fact he never stopped complaining how much his bones ached . . . What fun to see him run so clumsily though rather dangerously, like an enormous irritated boar. Which reminded them that for a short time mother and son had been partners in crime. But it also forced them to remember how quickly that complicity had come to an end.

The Osteria del Prete served chestnut puddings and Luigi Ippolito knew how much his mother liked such things: that was why he had taken her there. And why he had made her walk so far despite the cold. It gave Maddalena the chance to try the best marrons glacés she had ever tasted. Sometimes choosing a particular eating place can mean a lot.

“You do know I wanted to come back, don’t you? For the funeral, I mean.” It became clear that Luigi Ippolito had been waiting to say this from the moment he had seen his mother.

“But you didn’t come,” she observed, wiping a smudge of marron glacé from the corner of her mouth. She could expect anything from this creature who had started life inside her body but now seemed intent on stressing every possible difference between them. Children may term this progress even if their mothers, privately, call it desertion.

“No, I know I didn’t. When it came to the point, I didn’t feel up to it.” It was suddenly clear to both that the “love” they had once had for each other had been transformed into a battle for advantage. So while Luigi Ippolito was still trying to seem like someone who had no need for self-justification, he remembered a time when his father Domenico had said: “You are utterly without pity.” Which he had said as if talking to an adult rather than to a child of nine. Luigi Ippolito was indeed pitiless, there was no doubt about that, because if he had ever felt compassion he would never have been able to cope with what was currently happening to him.

“Yes, of course, that’s obvious . . .” his mother interrupted, having been aware of every one of his thoughts.

“. . . I had planned everything . . . But you know what they say here?”

“No, what do they say?”

“That if you want to make Our Lord laugh, tell him your plans.”

*

Maddalena had wanted a miracle from her son. She had specifically asked him to stop being so hostile to her. And even if she thought she was aware of the origin of that hostility, she pretended that, just as children cannot choose their parents, it is no less true that parents cannot choose their children. She had clear in her mind the exact moment when she had understood, beyond any possibility of doubt, that life with Luigi Ippolito would be a constant battle. Her long labour when she gave birth to him had influenced this belief, because it had taken twelve hours from the moment her waters broke to his birth. Twelve hours of bitter struggle like a violent negotiation between mutually hostile states, full of threats and modifications and mixed with blackmail and second thoughts thrown in. And when the creature finally emerged and Maddalena was forced to look at him, everything became clear to his mother. He had turned on her a terrible gaze of profound malice, and defying every instinct, had clamped his mouth shut against her nipple. The birth of Luigi Ippolito had inflicted labour on her in the fullest sense of the word. And she had had to admit, in relation to him, that deep down inside her, from that moment every single word had carried its full meaning.

“Aren’t you even going to ask me why I’ve come all this way to see you?” she asked as they made their way back to the guest house. Through some twist of climate, now that night had fallen it seemed less cold.

“I knew all I needed to do was wait,” Luigi Ippolito answered.

“I gave it a lot of thought after the death of . . . Domenico.” She could not help laughing, because instead of saying “your father” she had heard herself opt at the last moment for “Domenico”.

This did not escape her son. “Babbo,” he corrected. Maddalena waited for him to go on. “You had to think hard about that . . .”

Maddalena nodded. “But you, haven’t you ever wondered why you were called Luigi Ippolito?” she asked point-blank.

He hesitated for a second. “After our close friends, the Chironi family,” he ventured.

“Of course,” Maddalena said.

“But what has that got to do with it?”

The lights of the village were flickering in the rocky darkness of the valley.

Maddalena pulled the woollen scarf more tightly round her neck. They were walking the deserted streets with their arms entwined like young lovers. The mother in her thin clothing and borrowed scarf, the son in his immaculate and ample blue-grey suit.

“Naturally, as a future priest, it’s understandable you attach importance to appearances,” she threw in, letting her previous remark take its course.

“The Order pays less attention to appearances than you did with me, Mamma. From that point of view, as far as I’m concerned little or nothing has changed.” Luigi Ippolito’s answer seemed affectionate, if distant.

This detachment was painful to Maddalena. “Surely it’s not my fault?” she asked.

Luigi Ippolito, who perfectly understood this apparently obscure question, stood still and looked her in the eye. “You will be the first person from whom I have ever had to ask forgiveness.”

They began walking again.

“At the funeral everyone asked me about you, you know how it is in Núoro . . . Some people even wondered if there had been any problem between us.”

“Naturally, that’s the way they are.” Luigi Ippolito was careful not to miss the turning for the guest house. “I hope you took no notice of them, explaining too much is as bad as saying nothing at all.”

“Well, dear, you know how I am . . . I did say something.”

“The only thing that matters to me is that you should understand why I didn’t come. I prayed for you to understand!”

Maddalena shrugged. A way of lying without necessarily telling a lie. A way of saying that she understood only in the sense that she was his mother, that she was the person who had loved him, and that she loved him even more now that he was out in the world. She knew she had become a mother too soon, but she also knew that being so young had given her more time to hope this runaway son would come back to her.

“Come in for a moment. There’s something I’d like to show you,” she said when they reached the guest house door.

Luigi Ippolito swallowed a mouthful of frozen air and shook his head. “Tomorrow. You need a rest. We both do,” he answered as though speaking to one of the boys in his care at the seminary.

Maddalena realised she could not bridge the gulf his simple, almost subdued, refusal had provoked between them. “Tomorrow will do just as well,” she conceded, taking care not to seem in any way disappointed. “Come and find me here.”

“It’s very beautiful round here,” he said. “I’ll come and get you at midday, I’ve promised the Father Rector to bring you to lunch with us at about one o’clock, so you can show me anything you like then.”

“I don’t want to waste your time.”

“Of course you won’t be wasting my time, what do you mean?” he protested but without force, as though just mimicking words for the sake of it.

“I understand,” she said, suddenly brisk. “So everything’s alright then?”

“Everything’s fine,” his mother confirmed, as she always did when she was irritated and wanted to conceal it. “I’ll go in now,” she said, taking a step towards her son. Luigi Ippolito, surprised by what he imagined to be an attempted embrace, instinctively pulled back. Maddalena changed her aborted embrace into a clumsy farewell, as if taking her leave of someone who had boarded an already moving train.

Luigi Ippolito waited until she had vanished up the first flight of stairs. Then he turned towards the seminary.

*

The night had become pungent, its frosty acidity drying his palate. He had faced up to what remained unsaid and outdone himself. He realised he was sweating, and throughout the evening he had been unable to relax his shoulders. “Control”, he muttered to himself, exactly like it had been when as a child he had been aware of how difficult it was to work out if you chose or were chosen. Without being conscious of it at the time, he had told himself back then: “Control, control . . .” followed by “Here I am, if you want me take me.” His mother’s presence had reminded him how much strength he had needed to master that kind of tenacious flexibility. The sounds of the world, echoing round the mountains, were tense arches in his temples, chirping like a machine in action, like the clicks of well-oiled springs; there was nothing silent about the night though nothing seemed to be moving. The frost was merely a crystal bell on an old decorated clock. It was not a time for him to fall back into a whirlpool of reproaches, but to accept his own savage destiny. “You are utterly without pity,” his father had said.

“I have never had any time for compassion. For as long as I can remember. I believe that everything that I am, everything that I have become, derives from one absolute truth: which is that I have absolutely always avoided compassion. In relation to my parents, but also in relation to myself. Beyond that there’s not much to be said: I cultivate doubt, but not much, though I don’t let it be seen, within the mud of my obsessions. For example, my obsession with kindness, and the idea that in the last resort kindness does more for the person who exercises it than for the person who receives it. Is not kindness actually a form of pride? If it had been an ordinary feeling why would the Saints have invented it? In any case, what are the Saints if not simply professionals or champions, those so proud in their exercise of altruism that they are even capable of self-destruction, and thus of raising themselves through the altars up to the highest point in the sky. And what pity did He ever have when He abandoned me to my delirium? I was, perhaps, nine or ten years old, and I remember a maddening sky, and everywhere the stunning scent of prickly broom. What pity when I suddenly found myself at the centre of the whirlwind, a vortex like those described in the hagiographies every time the divine reveals Himself? Oh, I was innocent, so I opened my arms to offer my soft flesh to the downward slashing blade.”

Luigi Ippolito repeated these words as he bent down towards the pavement under his feet, as if talking to himself with head bowed like this signified surrendering to all the evidence, attempting an ultimate exercise in humiliation to cure the huge pride that had afflicted him only eleven years before, when he had explained to his parents what had happened to him, or what he thought had happened to him.

That day, at home, seated at table, he had heard himself speak in a language unfamiliar to him, and as if inspired by the very flame of Pentecost, he had dutifully described particular things he should not have known. He had spoken about himself, the sky, the smell, the slashing blade. At that midday meal every sound had been interrupted: the rhythmic throb of the pan, the drip of the tap, the chirping of cicadas, his mother’s breathing.

His father for a long time had not said a word, waiting for him to finish; then finally, “You are utterly without pity.”

*

In the cosy intestine of corridor that led to his own room he seemed to feel better. For no particular reason, the invasive smell of boiled cabbage from the refectory made him happy. Once in his room he threw himself on his bed without undressing or even taking off his shoes. Like a dead man ready for burial.

Next morning he made his way to the guest house at ten minutes to twelve. It was a beautiful day, glazed and pure. Nothing seemed to have been left to chance: points and sharp edges, roofs and aerials, gutters and chimney pots, the tops of fir-trees and whitened peaks. The scene was like a Flemish painting, its crisp edges dominating every possible roundness. And the compact turquoise of the sky seemed to contain no sunlight to fade it or the flight of any bird to stain it.

But when Luigi Ippolito reached the guest house he found Maddalena had departed by bus a few hours earlier for Torino. She had left a packet for the landlady to give to him as soon as he appeared, and this the old woman was careful to do. He accepted the bulky envelope as though it might be dangerous, and holding it tightly to his chest, hurried back to the seminary. Once in his room, he opened the package to find a collection of pages, some handwritten and others typed.

THE ANCIENT OF DAYS

Núoro, February 1979

ONLY A MOMENT AFTERWARDS, IT ALL SEEMED TO HAVE been absolutely impossible. Cristian fell back on the bed as if, far from slowing him down, his orgasm had given him renewed energy. Maddalena watched him reach for the underpants he had flung on the carpet and step into them as if the only thing that now interested him was no longer to be naked. In fact, with his underclothes on, he seemed calmer.

“We can’t do this to him,” Cristian said suddenly.

“What a shame you only think of such things afterwards and never before,” she remarked calmly.

“Domenico’s my brother. It’s not right.”

Then they fell silent; Maddalena realised how much Cristian needed her. Sh. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...