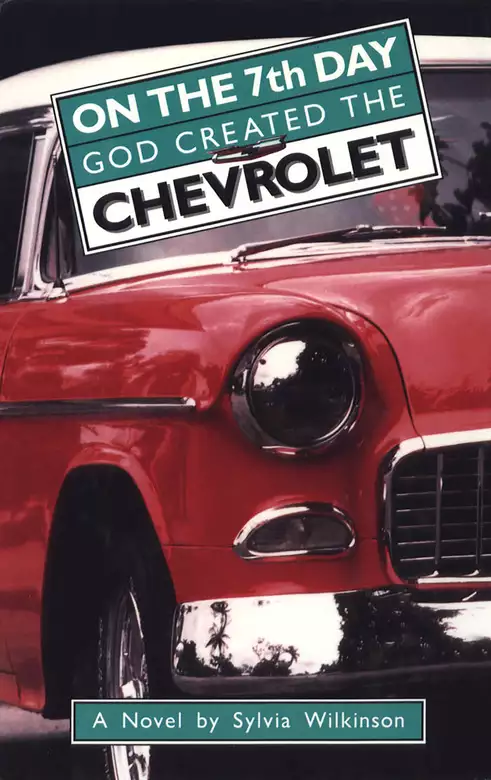

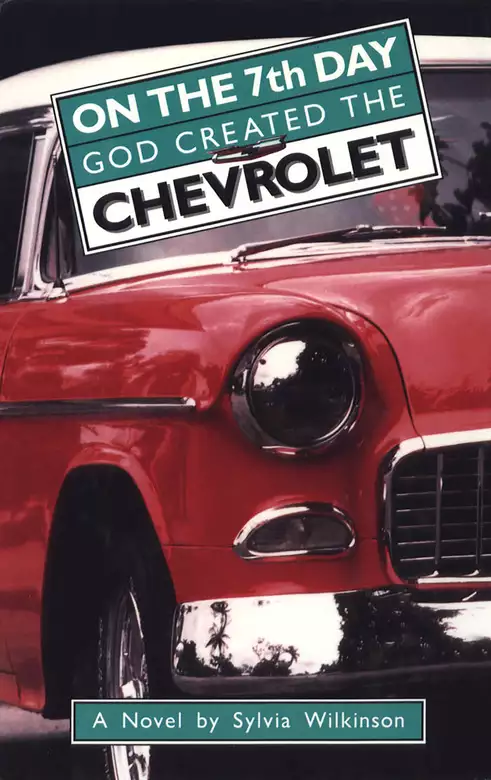

On the 7th Day God Created the Chevrolet

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Tom Pate can't leave the family farm behind fast enough. Drag racing his candy-apple-red 1955 Chevy Bel Air is just the first step in a journey that will lead him far from home in his search for a bigger track, a better ride, and a better, faster future. Tom's younger brother Zack tries desperately to keep up with this man whose talent involves leaving people behind. Set in the 1960s--with racial tensions running high and Vietnam War starting to make demands on the lives of young men--On the 7th Day God Created the Chevrolet is a story that pits the safe haven of farm and family against a young man's best shot at glory.

Release date: January 1, 2013

Publisher: Algonquin Books

Print pages: 424

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

On the 7th Day God Created the Chevrolet

Sylvia Wilkinson

After Tom hit seventeen, using money that emerged from his pocket like magic, he bought his dream car, a ’55 Chevy Bel Air. With his little brother Zack beside him, the familiar road to town branched out into an expanding labyrinth of pavement and dirt. Zack’s unspoken job was to figure out everything but the driving. If left up to Tom, they would just leave their farm, forgetting half of what they needed to carry. Or run out of gas. Or they would get lost and Tom would get mad. He would drive by road signs too fast for Zack to see them.

But Tom only had one speed—as fast as he could go. He drove his Chevy even faster at night than he did in daylight. A barrier of fur, flesh, and bone with silver orbs set in its face frozen in his headlights—Tom reasoned it stood in his path to prove he was fast enough to dodge it. And he did.

“I never killed anything,” he claimed, “not even a stupid old possum.”

Although Tom Pate got accused of a lot, Zack’s memory also says this is true. But even Tom can’t deny he hit a wall or two.

Tom’s big one happens in 1968 at Martinsville, the half-mile paved oval where he had broken his arm the year before. The race is two hundred and fifty miles long, five hundred trips in a circle, but before four hundred revolutions, Tom’s motor blows in a big way, catching fire on its own oil. His rear tires lose their grip as oil finds its way between the rubber and the pavement. He crashes straight in, his right foot hard on the brake of Bullfrog Embers’ red Chevrolet, the impact shoving the engine into the front of the cockpit. When his forward motion stops, he tugs on his right foot but it stays on the pedal. Flames off the burning oil come up past his knees, blackening the air he is trapped in.

Tom holds his breath, turning his face toward the window and reaching down into the flames until he feels his ankle. Then he pulls apart the twisted metal that grips his foot, an act he never could have accomplished in the shop. When he yanks open the window net and reaches through to lift his body clear, skin slides away from his hands; his gloves have melted. He drops to his knees on the track. The noise around him seems awful, worse than the engine explosion.

Maynard Peyton, his silver-haired crew chief, runs to the car with the bucket of water he had planned to dump over the radiator during the next pit stop and shoves both of Tom’s burned hands under the water. They sizzle like steak on a grill.

The awful noise passes again as the field of cars threads single file behind the pace car, snaking around his wreck.

“Only had one bucket,” Maynard grunts. “Get that foot in there too.”

Tom twists his body around trying to get his foot in the bucket, but now the emergency crew takes over. When Tom’s melted goggles are lifted from his eyes in the ambulance, he sees his hands and his foot and knows there should be pain, but there is none. The last pain he felt was in his ears when the engine let go.

Later, in the hospital, he hears Maynard talking but not to him. Then he hears a stranger’s voice: “Second degree, some third on the tips. May need a graft, but he’s young and healthy. His face looks bad, but it’s superficial. Just a bad sunburn. The goggles melted, but they saved his eyes.”

“Maynard!” Tom shouts. “You and that doctor get in here where I can see you.”

Maynard sticks his face around the corner and smiles. “You’re going to get well, Pate, okay? We’re just deciding how long he has to put up with you. Boy, are you ugly!”

The doctor walks across the room and picks up Tom’s chart from the foot of the bed. He seems too young. Tom doesn’t like that. And he isn’t Southern. Tom’s face itches. He lifts his right hand to scratch his nose, but to his surprise, his hand is a large white basketball on the end of his arm. The other one matches.

“The danger of infection must be past before he is released,” the doctor says.

As soon as the doctor leaves the room, Maynard says, “Hey Pate, you’re famous.”

“How’s that?” Tom replied.

“You know how they call Richard Petty, King Richard? You’re King of Turn Three at Martinsville. From now on they’re calling it Pole Cat Corner.”

“Are you going to let somebody else drive my car, Maynard?”

“Sure, I already hired him.”

“Not funny.”

“Take a couple of weeks before you’ve got a car again. And if anybody drives it, it’ll be me.”

“What if it had been my fault?”

“New guy in there for the next race, buddy. We don’t allow mistakes in this business. Tell that to the genius who built that engine.”

“You built it.”

“Right. And you busted it.”

After Maynard leaves, Tom tries to go over his words in his head. He can’t remember what they talked about. They must have given him something. He feels goofy.

He knows where he is. In the hospital, the same damn place in Martinsville. He sees a nurse pass his door, the same nurse he had after his last crash. “Hey,” he calls. She looks in with a smile: auburn hair, a turned-up nose, and a shape that refuses to hide under the stiff uniform. “Hey, yourself,” she replies and disappears. The last time she was his nurse, he’d just had a broken arm; he’d only pretended to be helpless.

He tries to push the covers back with his hands. He feels like he is in a straitjacket. He kicks at the sheet with his one good foot and sits up, dropping both feet to the floor. As he stumbles to the door of his room, he feels a draft. He looks down; he is wearing a skirt and his legs are bare from the knees down. There are bandages on his right foot and it hurts when he puts his weight on it. He makes his way slowly to the tiny bathroom. A black, greasy face with broken, peeling skin, skin that resembles an old coat of paint being attacked by stripper, fills the tiny mirror over the sink.

He tips his head from one side to the other; the black face tips at the same time. Maybe his nurse didn’t recognize him.

He goes back to his doorway and waits until she passes again.

“I bet you didn’t recognize me, huh?”

“You’re the same driver who got hurt here before.”

“I don’t do it all the time, really. Just here.” She starts to move on. “Wait a minute,” he says. “I want you to dial the phone for me.” He holds up hands that resemble giant white boxing gloves. “I need to call my mother.”

“Long distance?”

“Yeah.”

“We’ll have to use the pay phone at the end of the hall. I’ll get some change. Can you walk without assistance?”

“I’ll meet you at the phone,” he answers as he walks sideways down the hall, his back to the wall. The nurse places the phone on his shoulder and lifts his white mitt to steady it. He tries to smell her perfume while she dials the numbers that he calls out, but his nose doesn’t seem to work. She hurries away when she is done.

Gladys answers on the first ring. She sounds frightened.

“Hey, Mama. It’s me.”

“Tom. You’ve hurt yourself again. We heard it on the radio.”

“Yeah, Mama. I’m going to be okay, though, don’t worry.”

“Oh, thank the Lord. Did you break your arm again?”

“No, Mama. Just got a little hot in there is all. But look, right now I need some help if you know what I mean. I mean, I’ve got these big bandages on my hands and I can’t do anything for myself. I couldn’t even dial the phone. I can’t hold a spoon or do a button, or a zipper. I have these itches all over me I can’t scratch. It’s kind of embarrassing, Mama. I mean there’s some things I’ve got to do, like soon.”

“Tom, don’t they have someone there who can do that for you, a nurse?”

“Yeah, I’ve got a nurse. But I was kind of hoping you could come up here . . .”

“Oh, Tom, I can’t possibly leave right now. It’s your daddy. I can’t leave him alone a minute. He goes walking off and we have to go out looking for him. I’m scared to death he’s going to wander off and we won’t be able to find him. His mind isn’t all there anymore. You knew he had another stroke? No, I guess you didn’t,” she answers her own question. “If you would come home, Tom, I could take care of both of you just fine. If you’d get one of your friends to bring you or I could send Zack. He took everybody to the beach for the weekend, but when they get back . . .”

The operator interrupts. “Your three minutes are up, sir. Deposit fifty cents more, please.”

“Tom, what shall I do?” Gladys pleads.

“I can’t get my hands in my pockets, operator. I don’t have my wallet,” he talks as fast as he can. “Mama, never mind. I hope Daddy is feeling better, okay? I’ll work it out. I’ve got to go now. I . . .”

The phone goes dead. Tom lets it roll off his shoulder. It bangs against the wall. He kicks at it with his bad foot, but stops short of letting it hit. He sees a woman at a desk at the end of the hall, so he edges up there, addressing her from across the hall, his bare backside to the wall.

“I left the phone off the hook,” he tells her.

“I can’t hear you,” the woman says without looking up.

He moves toward her, crossing his bandaged hands behind him. “I couldn’t hang the phone up.”

When she sees his face, she grimaces. “I’m sure the next person past will see that.”

“How do I go about getting a different nurse?”

“Who is your nurse?”

“Sally.”

“Sally! You don’t like Sally? Everyone likes Sally.”

“I don’t like her. I want the one I saw go in the room across the hall. The big one with the red nose and short gray hair.”

“Mildred.”

“Yeah, Mildred. I want Mildred to be my nurse.”

“I’m sorry, young man, but without a legitimate complaint, you don’t get to change nurses. Besides, Sally is in charge of this floor. Mildred is just a scrub nurse.”

“Okay, okay. Here’s my complaint.” He leans over, but she backs away as if he smells bad. “Sally’s a personal friend,” he presses on. “I mean we went out a few times, okay? What I really meant to say is she kind of has the hots for me. It’s sort of embarrassing, but. . . .” He leans over farther to whisper and the woman rolls her chair backways. “I . . . never mind.”

He turns to leave, forgetting his bare backside for a moment before he spins around again on his good foot, sidewinding back down the hall. His burned foot is starting to hurt. He checks the corridor before he backs across the hall into his room.

There are voices outside, but no nurses pass. He kicks his wastebasket over, dumping the ugly contents of cotton and gauze. His face is stinging. He goes into his bathroom. Hot tears run through the grooves on his face. When he presses the giant ball of gauze on his hand to his face, it grabs at his loose flesh. He can’t even tell if there is a hand inside the white ball. He can’t move it.

He can’t hold it much longer. He tries steadying his penis between his two bandaged hands. No good; it slips away from him. He leans against the wall, shifting the weight to his good foot and lifting the bandaged one. That doesn’t work either. He can’t hold his balance on the bad leg. He straddles the toilet, trying to gather up the cloth of his gown, when suddenly he feels a cold hand on his organ.

“Hurry up, okay, buddy? I got work to do.”

He turns to face her, seeing her through his stinging eyes. She doesn’t recoil from his damaged face.

“Mildred?”

“Yeah?”

“Okay, I’ll hurry. Just let me think about it a second. Maybe if you turned on the water in the sink and I could hear it running, that would make it come faster. Don’t go and leave me, okay, please? I know I can do it. It’s just different is all. I really appreciate this, Mildred. You’re okay. Finally I meet the woman of my dreams and she’s rushing me.”

Before the end of the season, Tom Pate is racing again. The stiffness in his hands when he shaves or buttons his clothes is forgotten when he drives Bullfrog’s race car. There isn’t even a dent in his confidence, though he jumps out of the car a little faster when one of the crew guys yells fire while working on his overheated engine. He shivers when Fireball Roberts’s niece tells him that after her uncle died in a fiery crash the funeral home sent the family a smoked ham. Now Tom has to wear a cap because the skin on his face sunburns easily. But he loses nothing on the race track.

“Do you really feel that good or are you trying to convince me?” Maynard asks during a practice break at Waverly, Tennessee.

“Just look at my laptimes. What do they say?”

Maynard smiles. He tells Tom a story. “I had this old dog once back on the farm. He lost one of his hind legs, tore it off in a muskrat trap. Old Cottonpicker would go up to a tree and lift that leg like he needed to. And he’d set down and kick fleas on the back of his head with the foot that wasn’t even there. Smiled just as contented.”

“Save that story for my brother. That’s the kind of stuff I’ve had to put up with from him all my life.”

Maynard frowns and shakes his head. “I’ll save it to tell to you again when you’ve learned enough to understand it. When do I get to meet Zack? I want to meet the Pate who has some sense.”

“Not for a while.”

“You know, I can’t figure what’s the matter with you young guys. Why don’t you get that war won and get it over with? I hate to even think it, but I’ve got a feeling you’re losing this one.”

“I didn’t lose,” Tom defends. “I just went over there and did what a bunch of old guys like you told me to do.”

“General Patton said we have never lost a war,” Maynard adds with a smile, “but his grandfather fought with Lee in Virginia. Guess it’s all in how you want to see things.”

“I can’t tell what you’re talking about half the time, Maynard.”

“I know you can’t. And you don’t even bother to listen if I’m not talking about racing. But that’s the way drivers are, even the good ones. Lorenzen couldn’t have found his way around a cornfield on a tractor if it hadn’t been for Ralph Moody coaching him.”

“I thought Lorenzen was a carpenter.”

“That’s exactly what I mean, smart guy. But he was a hell of a race driver while he lasted.”

“I’m a hell of a driver too,” Tom answers, ducking Maynard’s playful punch.

“I know it. I know it. You tell me every day. And every now and then, you show me.”

During the next session, Maynard’s good mood begins to fade. Tom’s laptimes have ceased to improve. Maynard tells him where to drive coming out of the turns, but he fails to change his line. He isn’t running close enough to the wall.

“It’s too loose,” Tom complains when he pits.

“I’m not telling you again, Pate!” he shouts. “Quit bitching about the car. It ain’t the car’s fault. The wall’s just sitting there. It ain’t jumping out in front of you.” Maynard empties his pockets of tools and approaches the driver’s window. “If you can’t do as I say, then maybe you will do as I do. Get your ass out of my car,” he orders.

Maynard climbs in, throwing out the seat padding. He takes one warmup lap before putting the car where he wants it. He keeps going for two straight laps, obviously enjoying himself and delighting his crew. When he pits, Tom is gone.

“You want me to go find him?” one of the mechanics asks.

“Naw. Let him stomp off and have his tantrum. I bet he stuck around long enough to see me do it right.”

Tom comes back and, following Maynard’s path out of the turns, puts the car on the pole.

“Well, Pole Cat,” Maynard snorts. “At least you’re not so big for your britches that you can’t learn something.”

Tom keeps his thoughts to himself. When he was a little boy, his uncle Vernon had told him that Little Joe Weatherly and Curtis Turner put their britches on one leg at a time like everybody else, so Tom started lying on his back to put both legs in at once.

Tom Pate finally wins his first Grand National that Sunday in the Labor Day Clash at Waverly.

“I think I could have beaten Petty,” he tells Maynard when they are loading his trophy into the truck, “even if he hadn’t broken.”

“Yeah, then why weren’t you beating him before he broke?”

Tom smiles and leans against the truck. “You know what Petty says: the last quarter mile is the only lap that counts. You just run the others for exercise.”

This time Maynard keeps quiet. He sees that all it takes is one trip to the victory circle for Tom Pate to feel that he belongs there.

When the Pate boys were little, their mother sent them on an errand in Summit, handing Tom the exact change to pick up a package at the dry goods store. After old lady Brunswick mistook a nickel for a quarter and gave him two dimes change, Tom bought two double scoop cones—one for himself and one for his little brother, Zack.

“If she’d just given you one dime too much,” Zack questioned in his customary way, “would you have gotten two single scoops or one double scoop?”

“I’d have given you a lick,” Tom laughed.

Tom Pate was ten when he discovered that rivers only run just one way. Zack could only watch as his brother spun out of sight. Tom’s naked body in the tractor tube looked like a white cup in a fat black saucer. He rode the Yellow River almost to Raleigh. He tossed his tube over a post on a private dock and walked to a gas station, where he talked a pretty lady into a quarter for a Tru-Ade and an oatmeal cookie. “I forgot my wallet,” he said, and shrugged. She handed him the money with her hands over her eyes. Then Tom offered a Merita bread driver five dollars he didn’t have for a ride back to Summit, negotiating as naked as a jaybird while his mother sobbed over his empty clothes back home on the riverbank.

Hershel Pate got a call from the Wake County sheriff to come get his son, and during the ride back home, Tom described his close calls on the river—bouncing down the paddle wheel at the old mill, speeding past a dozen sleeping water moccasins. Zack asked his daddy to stop the truck, got out, and rode home in the inner tube in the back of the pickup, clutching his glasses in his hand, the wind drying his tears as fast as they fell from his eyes.

Two years later on a Saturday in June, Tom hatched secret plans for Zack to join him on another journey away from the confines of North Carolina farm life. A skywriter glided over Goose Bottom community in a red and white Piper Super Cruiser, dancing through smoke letters with the grace of a swift chasing a mayfly over the pond. After the pilot finished his words, COCA-COLA, the COCA broken into scattered puffs before he shut off his COLA smoke, he dove to an unknown place to the west of the Pate farm. The Pate boys watched him disappear, as if he rode down a rainbow to a pot of gold.

“Where you reckon he goes to, Tom?” Zack puzzled.

Tom didn’t answer. He was set on greeting the pilot after he landed on the grass strip near the Summit city limits. He planned to beg a ride. He jumped on his bike, the one he had recently ridden into a tree while admiring the smoke from an iron pipe stuffed with gasoline-soaked cotton on his rear hub. Tom pedaled the wobbly bike with the bent front wheel out the driveway and on down the road.

The next Saturday, Tom rushed Zack through their chores without explanation, shucking corn in the crib with the speed of a machine. A gust of wind grabbed their attention—the devil’s breath—and the crib door slammed and caught on the new latch their daddy had installed. Tom jumped at the door, fighting it like a dog with its head stuck between two railings, kicking it so hard the whole structure rattled.

“That’s not going to make it come open,” Zack said. “You’re just wasting your time.”

Tom swung around on his haunches, diving after Zack, who scrambled up the pile of corn. The ears rolled out from under the smaller boy’s feet, sending him sprawling down onto Tom’s brogans. Tom kicked Zack until the younger boy gasped for air. Then Tom crouched down by the door, his face buried in his arms. Zack crawled over slowly and sat beside him. As Zack lifted his shirt, Tom glanced at the raw red spots on his little brother’s stomach and shivered. He had left the red imprint of the star off the bottom of his brogan in three places.

Their silence was broken by the airplane. Tom rolled onto his side and looked upward through the slats. Then he pounded the corn until his knuckles were raw while he listened to the stops and starts of the skywriter writing words he couldn’t see in the plane they could have been in.

When Tom Pate was twelve, he’d got a tickle when he shinnied up the pole on the monkey bars in the Summit Park playground. Zack had tried it and said he felt the tickle too, but he really didn’t. By now, a year later, Tom didn’t think about the tickle on the monkey bars; it was there all the time.

One day that summer when he saw a flash from the sky and felt the first sharp drops, Tom started to get the whole picture. He dropped his hoe in the backfield. Next he pedaled to Parsons’ Garage to watch them put together a flathead for the jalopy race, with thunder in the distance like airplanes heading into the sky. Then he rode by the high school to watch Holly Lee Pedigrew practice her twirling alone, until she ran to the bus stop, carrying her baton like a lightning rod as the sky over the ball field blackened with storm clouds. Something was stirring in him; looking at wrenches turn and Holly Lee twirl made it churn faster. He rode back to their pond, stripped down and jumped into the water.

Zack saw him diving repeatedly into the pond, pulling himself up to the pier with just his arms. Each splash back into the water ripped through Zack’s ears like an unmendable tear. His brother had a farmer’s body: two halves sewn together at the waist, the top half brown, the bottom half white flesh that only saw the light of day when he swam. Zack put his fists over his eyes to shut out the vision of Tom’s two-toned body frying in front of him like a strip of bacon. He couldn’t believe it; Tom was swimming in a lightning storm.

“Come on in, sissy britches,” Tom called when he spotted Zack. He slid his hands down his white legs, setting the mud loose from the hairs like brown blood.

“Tom, it’s not just some dumb rule that Mama made, okay?”

Yet because Tom had told him to, Zack slowly pushed his shoes off, undid the straps on his overalls, then rolled his glasses up inside. He shoved a red frog with his toe and as it hit the water, Tom shot up from underneath, spurting a stream from his mouth. His brown chest glowed white from the flash and the thunder hit hard, before the light had faded.

Zack began to sob because he knew he wasn’t going in, “Please, Tom, get out!” He ran up the hill to their house, falling in the slick manure on the path and crunching his glasses inside his clothes. He yelled one more thing but Tom didn’t hear him over the thunder: “You’re going to die, Tom Pate!”

Before supper Tom came inside, soaking wet. His mother met him with dry clothes and a towel she had warmed in the oven. “It started raining when I was in the lower field,” he said, which wasn’t a lie. He spotted Zack watching him from the stairway as he peeled down his wet underpants. He crossed his hands over his organ and pressed his knees together, doing what they called “Mickey Mouse at six-thirty.” Zack squinted.

“Where’re your glasses, four-eyes?”

“Where are your glasses?” their mother repeated from the kitchen. “Not another pair broken!”

That night when they were talking in bed, Tom explained his revelation to Zack: “Are you starting to get the picture around here, Zack?”

“What picture?”

“Listen, I got it figured out. See, this is what farming is all about. You watch your calf get born. Here’s the picture that goes on the 4-H poster: this little kid in a clean pair of bibs and a fat calf with the crap washed off his tail. But you know that baby calf gets ugly and turns into a cow and gets eaten. Same with seeds. You plant seeds and it’s supposed to be really neat when they come up, only you know you got to chop out the grass and there’s always going to be too much squash and they’ll make you eat it till it runs out your ears. Either there’s no watermelons or so many of them you lose your craving. Then you get old and fall off your tractor and die in the dirt. That’s what it means to be a farmer.”

Tom drove his ’55 Chevy Bel Air up his driveway, horn blasting for the family to run out to see his new paint job, the color shimmering in the sun like a creek running with fool’s gold, two-toned, red with pearl white trim.

Everybody liked it but Hershel. Even Rachel, his big sister, who thought red nail polish was gaudy. “It’s a little loud,” she said flatly, “but it’s pretty.”

“I wouldn’t have picked it,” Gladys said, “but it does suit you, Tom.”

“Good enough to eat, like the candy apple you got me at the fair, Tommy.” Annie, the baby, shouted. She tugged on her big brother’s hand. “I wanna go for a ride.”

“It’s the same old car, Annie,” Rachel said.

“Well, it looks different.”

“Red hot,” Zack said, with his thumbs up the way Tom did.

“Yeah!” Tom gave him a big smile and thumbed him back.

Hershel turned to go back into the barn, but Tom sprang in front of him. “What do you think?” Hershel stopped, balling his fists that were black with engine oil from his broken tractor, but not looking Tom in the eye. “What was wrong with the blue it come in?”

“Everybody’s is turquoise blue, Daddy.”

Hershel stared at the barn door; for a minute he didn’t move. Then he swung around and pointed an oily finger at Tom, inches from his nose. “You really want to know what I think? I’ll tell you what I think. I think the day that car come in this driveway, I got the last lick of work out of you. I think you’re a speed demon. And as for that color, I don’t know where my son got his colored blood.”

“Hershel!” Gladys cried.

“I wanna go for a ride,” Annie repeated hopelessly.

“Not today,” her mother answered. Zack was already in the front seat beside Tom.

“Where we headed?” Zack asked as they turned onto Highway 43. He hung on as Tom peeled rubber for forty feet.

“The Blue Moon,” Tom replied. “Screw him.” Then he smiled slightly and added, “I know who’s gonna love my paint job.”

Soon after he had financed his Chevy at the Cut-Rate lot in Butner, Tom became a regular at the Blue Moon Drive-In, where girls skated up to the car door and hooked a tray on the window. When he drove in that Saturday, three carhops drifted around the lot, appearing as aimless as butterflies, yet with their eyes set on the window of his glistening red Chevy as though it was the only flower there with any honey. Then they went into formation and headed to Tom’s window. Zack dreamed of those girls at the Blue Moon with half moons of flesh slipping out the backs of their too-short short-shorts and their fronts rising like his mama’s yeast rolls. When one of them rested her elbows on the sill, twelve-and-a-half-year-old Zack slid up in the seat so he could see down the front of her tight uniform.

In Summit there was one place to go. One station to listen to. One car to covet. And one girl to desire: Holly Lee. At first Zack thought her name was Meatloaf, which was what the tag said that rested over where he imagined her left nipple was, but when she leaned in the window, he saw it said in smaller letters: TODAY’S SPECIAL.

“I love it,” Holly Lee acclaimed. “My favorite color.” Zack saw that she wore a lace bra with a piece of curved wire that had worked out of the cloth, pressing a dimple in her left breast.

“Thanks. I wanted you to be the first to see it.”

“Root beer float, right?” Holly Lee asked Tom as she elbowed the other carhops away. Her hair clustered in golden curls around a round red cap cocked to one side with a chin strap, the crown of the chief carhop. Her waist, wrapped in a black cummerbund, was small enough for a set of man’s hands to encircle. Her face was beautiful except for one flaw: one of her front teeth wasn’t white, like a piece of wood in a fence that needed painting. “That your little brother?” she asked.

Zack’s face heated up as he turned away, wondering if she was thinking that he was looking at her dark tooth or down her blouse, or both. Tom nodded with a smile, not looking directly at her, but at the space between the steering wheel and the outside mirror.

“Cute little guy,” she commented. “Too bad he’s got to wear big old glasses to cover up them pretty eyes.”

Holly Lee brought the floats, one large and one medium, hooking the tray to the window.

“Careful. Don’t scratch the paint,” Tom cautioned. He unhooked the tray and took it inside. He didn’t reach for his pocket, so Zack began counting out his change, figuring he’d have to pay for Tom’s, too.

“Put it up, Zack,” Tom ordered and shoved back his brother’s hand full of change. “Or, give it to Holly Lee to bet on me tonight. I’ll quadruple your money for you.” Tom gave Zack’s thirty-five cents to Holly Lee, who dropped it into her apron pocket.

Every Saturday night after the sheriff was in bed, on a quarter mile of pavement outside of town, the Night Owls gathered at midnight with their cars

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...