- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

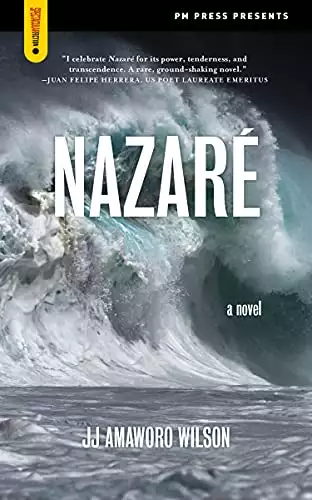

Nazaré tells the story of a peasants’ revolt in the polyglot city of Balaal. The story begins with a miracle. A homeless boy sees a whale washed up on the beach. He alerts the local fishermen, and soon the whole town is trying and failing to push it back into the ocean. With just the boy left to accompany the whale now in its dying throes, a freak wave pulls the creature back into the sea. This is an omen. Change is coming.

The boy and the washerwoman who adopts him cobble together a ramshackle army of fishermen, shopkeepers, lapsed nuns, anarchist bats, and an itinerant camel. They attempt to end the reign of the dictator who rules over Balaal. Their attempt involves pitched battles, farcical trials, rooftop escapes, and sun-parched wanderings in the wilderness. Looming over the disparate cast of characters is the legend of the giant wave—Nazaré—that will one day annihilate everyone and everything in the city.

Nazaré is an adventure and a parable that pits the oppressed against the oppressor. The work has been likened to that of Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa in its use of language, its inventiveness, its humor, and its examination of issues of justice.

Release date: September 14, 2021

Publisher: PM Press

Print pages: 301

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Nazaré

JJ Amaworo Wilson

CHAPTER 1

Balaenoptera musculus—Kin—Shadrak—Jesa—the town descends—holy man Fundogu—rice and beans—Nazaré

AT 4:30 A.M. ON JUNE 30, EVERY DOG IN BALAAL BEGAN TO BARK. PAMPERED POOCHES IN the mayor’s palace yelped at the chandeliers, mangy street hounds growled at a cloudless moon, and guard dogs yanked at their chains and bawled into the dark. It was a canine protest. A crescendo of “no! no! no!” because that was the moment nature was breached. The moment a sixty-ton blue whale washed onto the beach.

A boy called Kin rose from a dreamless sleep inside the shipping container he called home. He sensed a change in the atmosphere and a smell of brine and flesh more pungent than ever before. The port along the way was silent at this hour. There was no sound but the insistent wash of the waves.

He rubbed his eyes and walked the fifty yards to the beach, past other containers where other children slept, and he saw the whale. At first, he didn’t know what it was. Just a dark mound on the sand, like the outline of a low hill. As he approached, the features began to clarify in the early morning light: the pectoral fin, the bifurcated tail. The whale was stranded on its belly, half in, half out of the water, parallel to the breakers. Gentle waves lapped at its flanks.

Oblivious seagulls flew overhead and a light breeze jostled the grass of the hummocks that fringed the beach. Balaal, city of tinkers and fishermen, slept as the sky turned orange with the first stirrings of the sun.

Slowly Kin circled it. He saw water and air bubbling from its blowhole and heard the rumbling of what sounded like a breath emanating from its belly.

The whale was a mottled gray. White and black spots covered its back as if a painter had flicked a loaded brush at it. The skin shone with a watery sheen.

Kin, at eleven years old, had seen whale fins in the distance and heard whales bellowing to one another in the deep. A child with music in his bones, he’d once perceived the sound at A minor and thought it was a ship’s mournful foghorn until one of his sailor friends told him, “That’s a blue whale, ten miles out.”

Kin dared to get closer. The whale’s presence was otherworldly—a colossal mass of indistinct blubber. It looked like a fallen zeppelin, and its stench permeated the beach.

He walked past the boats anchored off the shore to the village where the night-fishermen were bringing their catch to be placed on ice and gutted. The first person he saw was Shadrak, an old black fisherman with a round belly.

“Shadrak,” he said, “there’s a whale on the beach.”

The old man smiled and nodded. He had a fishing rod in one hand and the butt of a cigarette in the other. He blew a miasma of smoke.

“And it be good mornin’ to you, young shrimp. You tellin’ tales?”

“No. I just saw it.”

The old man coughed. “Where?”

“There.” Kin pointed. “On the beach.”

“How big?”

“Huge.”

Shadrak took a final drag of his cigarette, a mess of rolled newspaper and foul-smelling tobacco, and dropped it at his feet.

“I go get some men. We take a look.”

Kin walked on, a little inland, away from the whale, until he came to more fishermen unloading their catch, and he repeated his story. A few of them knew and trusted him. Some put down their tools immediately and began walking toward the ocean. A few old hands laughed it off. “They stink up the beach is all they good for.”

By the time Kin returned to the whale, there was a crowd. Several women were carrying buckets and throwing water over its gargantuan body.

Kin saw Shadrak with a group of fishermen and asked him, “Why are they doing that?”

“Whale skin dry out in the sun, whale die.”

One of the women, who was called Jesa, saw the group of fishermen and shouted, “Hey!” They looked at her. “Call Fundogu,” she said. “Tell him to bring a stethoscope. We’ll need your fishing boats. He’s too big to push by hand.”

None of the men moved.

“Hey, estúpidos!” she shouted again, pausing from throwing water on the whale’s back. “We don’t have much time. When the tide goes out, the whale will be stranded.”

“It’s stranded already,” said a fisherman. “What’s your plan?”

“What do you mean, what’s my plan? We’re going to rescue it. Put it back in the ocean.”

Another fisherman moved forward, next to the first, and said, “How we gonna move it?”

Jesa said, “We’re going to use your boats, tie lines around it, and then you drag it out to sea.”

There was a murmur, a shaking of heads. More people appeared on the beach so now the crowd numbered a hundred. Some inspected the creature, walked around it in awe and silence.

The mayor arrived in a suit, along with six pampered dogs and a retinue of soldier-bodyguards, who were called the Tonto Macoute. The villagers shuddered at the sight of them and parted to let the mayor through. He had himself photographed next to the whale, prodded it with his cane, and went home.

A priest arrived on a bicycle, soon followed by a gang of harlots in fishnet tights and a drum troupe and trapeze artists from a travelling circus. An acrobat danced on the whale’s back until Jesa shouted at her to get down because “the beast is sacred!” A hot air balloon soared above the scene and its pilots, from neighboring Bujiganga, looked down upon the whale and marveled.

Then came the widows of the fifty lost miners—los desaparecidos. Then troubadours and vagabonds from Balaal’s back-streets. Kin’s neighbors, the homeless kids from the stray shipping containers, emerged. And other kids who lived in the containers at the port along the way and who had addresses: third container, second row, Hawagashi Electronics, or second container, fifth row, Köstlich Foods.

There was an appearance from the Bruja of Laghouat, although no one knew it because the witch came in the form of a seagull and observed events from far above.

Down below, a bus cranked and creaked to a stop on the sand and disgorged a rabble of schoolchildren. They ran to the whale and made notes and drew pictures, eyes agog, nostrils aquiver at the smell.

The radio station took a break from its nonstop government propaganda and ran a story on the whale, complete with fake whale noises. Journalists from Balaal and two neighboring cities came and took photos and interviewed the locals.

“It’s a gift,” said the priest, leaning on his bicycle.

“It’s an omen,” said the fortune-teller.

“It’s big,” said the acrobat, still out of breath.

A posse of loosely affiliated dogs came nosing along the beach to catch the commotion, tails erect at this new wonder. To them everything was in two categories: Dog or Not-Dog. But this creature seemed to herald a third: Undog. Unlike Not-Dog, Undog was the very antithesis of Dog: huge, not moving, and incapable of wagging its tail.

Then came twenty-five Believers, who gathered sticks to build a fire and sat in a circle around the whale and made incantations and said the whale was a god.

A woman who had been shooing the dogs away asked, “Who found it?”

“This boy,” said Shadrak, pointing at Kin.

The crowd parted to make way for Fundogu, who was a holy man and a doctor, which were the same thing in Balaal. He was large and black and in his seventies, with tribal scars down both cheeks. He wore a white gallabiya—a long embroidered robe—and no shoes. With great ceremony, Fundogu inspected the whale. He circled it, touching it with his long, ringed fingers, prodding at some parts, massaging others. The whale blew a jet of vapor and Fundogu pulled out a stethoscope from somewhere within his robe. He had no idea where to put it, so he placed it against the whale’s vast back and leaned down to listen. The crowd murmured its approval of the learned man.

During the inspection everyone had retreated a few feet except Jesa, who continued to splash sea water on the whale.

“This whale,” pronounced Fundogu, “is a distraction.”

There was an audible gasp from the crowd and then a flurry of whispered questions. No one knew what “distraction” meant.

“It’s this boy,” Fundogu continued, and he pointed at Kin. “It’s this boy you should be looking at. The future is his.”

There were more gasps, some nervous laughter.

“But what of the whale?” asked the woman called Jesa.

“Get him back in the water or he will die.”

With that, the holy man wandered off, head held high, through the human corridor that had let him enter. His large flippery feet were damp with wet sand. Before leaving the beach, he turned, looked again at the boy, and whispered to himself, “Everything begins and ends in the sea.”

Jesa called to the fishermen, “You heard him. Get your boats ready.”

Shadrak stepped forward and said,

“No can do use our boats.”

“Why not?” said Jesa.

“Our boats not big enough. We take this whale into water, he pull us under before we cut the line. He drag us down, boat and man ‘n’ all. No can do it.”

Jesa dropped her bucket into the sand. Some of the other women who had begun throwing water at the whale also stopped. Jesa crossed her arms. She was in her mid-thirties, already a widow, her husband claimed by the sea. She had no progeny and wore a black scarf around her head in memory of her drowned beloved and to hide a vivid streak of white hair. It had turned white the moment she had heard her husband was dead, and the Spanish-speaking kids had taken to calling her zorrillo—skunk.

“This is a sacred animal,” she said. “Older than me and you. It was sent here by God. Put your boats to work, you weaklings, and cut the lines when the whale’s in the water. We’ll send divers down to do it.”

The fishermen were unmoved.

“Too risky,” said Shadrak.

Jesa squinted her eyes at him. “Then I’ll do it.”

“You no got no boat, remember?”

Jesa approached Shadrak as if to slap him. She had lost the boat at the same time she had lost her husband, both taken by the sea. Shadrak didn’t flinch.

“Miss Jesa, I would like help you,” he said. “But my boat is my livin’. No boat, no fish.”

Jesa looked around at the other fishermen. A wiry Somali. West Indians stripped to the waist. Pacific Islanders with tribal tattoos. Lean, weather-beaten Japanese. Not one looked her in the face. The whale breathed again and its massive eye opened to take in the sky and the flitting birds.

“Which of you will lend me a boat?”

The men looked at their feet. No one lends a boat to a water widow.

“Then we’ll bring every man and woman in Balaal and push the creature back into the sea.”

With that, the women with buckets wheeled away to gather reinforcements. Others followed them.

It was at this moment, with the crowd streaming away, that Kin alone heard the whale singing. He heard three notes in a minor key, a threnody of such sadness that the whale’s mottled, dark skin seemed to tremble with the song. It sounded to Kin as though the notes conjured all the beast had seen: the glistening shoals of fish; kaleidoscopic reefs with their jagged edges; seaweed wavering like witches’ hair in the tides; sunken galleons lost and canted on the seabed; the underside of trawlers and skiffs he could have upturned like toys; sunlight bursting through the water like the beams of torches.

The song ended as abruptly as it had started.

For the crowd was back, and many others with them. Volunteers, streaming down the beach, the pushers and pullers of stranded whales. Jesa ordered them in five languages to take their positions. They were going to roll the beast back into the ocean.

As he joined them, Kin could see the tide receding. Where the whale had been half-under at first light, it was now barely in the shallows.

Two hundred people were amassed now at the whale’s side: bakers and road workers, farmhands, schoolteachers, knife sharpeners, cat catchers. They gathered their strength, sucking in the sea air, placed their hands on the colossal wall of gray-black flesh, and heaved with a cry that faded into groans and gasps. The whale didn’t move.

Forty of them brought out shovels and wheelbarrows and dug a vast trench toward the sea to reduce the drag of the sand, to ease the whale’s passage to the water. They rasped instructions to one another, mimed and gestured, wheeled away and dumped their loads of sand, even as the new ditch began filling instantaneously with water. The people took their places again and, with a shout, pushed with all their might to roll the great beast into the channel in the sand. The whale didn’t move.

Three fishermen—islanders squat and sun-browned—appeared reluctantly and tied ropes to the whale’s flukes and flippers. In groups of thirty, the people gripped the ropes and readied themselves like contestants in a tug of war. The remaining fishermen joined in, put their shoulders to the whale’s back. At the water’s edge one of the drummers from the circus troupe started up a beat on his djembes. The man, who’d been born with four arms and now whacked out a rhythm on four drums, went faster and faster till the sweat flew off him in his frenzy, and as the pounding came to a crescendo and the sun climbed higher, the people of Balaal heaved and shoved and pulled as they’d never heaved and shoved and pulled in their lives. They gritted their teeth and strained every sinew and summoned from nowhere the strength of the ancestors. The whale didn’t move.

The people looked at one another. They were spent. Bruised and cut where the rope had worn a groove into their skin.

Shadrak picked up his straw hat, which he’d temporarily laid on the sand, and said, “He no gwon move.”

The fishermen untied their ropes from the whale and people began to walk away.

A woman approached Jesa and said, “We did our best. All this pushing and shoving is going to kill it anyway. There’s only one chance now.”

“What?” said Jesa.

“The magicians are here.”

A raggedy cluster of shamans arrived, most of them naked or wearing nothing but loin cloths and necklaces made of seashells. They were preceded by the smells of pipe smoke and ganja weed. They were alchemists, windtalkers, adepts, thaumaturgists, Voodoo priests.

They lit a fire under a cauldron and mixed metals and threw in bindweed and dandelion and the spines of long-dead starfish. Some whispered incantations in languages not heard for a thousand years. One blew mapacho smoke into the pot and sang to the whale in a voice so pure the stones in his pocket began to dance. And when all their spells were said and done and all their gods summoned, still the whale didn’t move.

By late afternoon, the shamans had melted away into the distant rocks or returned to the hills, and the crowd was thinning out. Jesa had gone home, leaving just a few women to throw water onto the whale’s back, careful to avoid its blowhole, and to warn the children to stay away from the thrashing flukes. Then even the women and children went home.

As the sun went down, Kin sat alone beside the creature in the sand. Steam came off its skin and its eye rolled above the grooves of its ventral pleats. Kin listened. There was no song, but he thought he detected a low moan.

He looked beyond the creature at the island of the abandoned lighthouse with its cluster of vegetation and the cracked, useless phallus of the building itself. Kin wondered if the whale had skirted the island on its journey to the sands of Balaal.

With the last of the women gone, he kept the creature company until he heard its breathing change. He stood up and stepped back. All around, seagulls flitted and yawped and watched this child in rags staring at the mass of blubbery flesh.

Kin hurled himself at it. He put his shoulder to the whale and pushed, running in place, kicking up sand till his feet sank. “Move, damn you!” A crab darted from a hole, looked quizzically, then skedaddled.

The stench was now tremendous, a mélange of rotted fish, garbage, and salt. It was as if the whale were inside out, discharging the fetor of its guts. Kin ignored the smell. He pulled at the creature’s flipper. He yanked at the whale’s fluke, which lay immobile, a massive dead flap.

He exhorted the creature in all the languages he knew. He hollered and sang and begged and howled. He clambered on top and looked into its eye and pointed at the sea.

At last, he climbed down, bathed in his own sweat and tears. His legs were trembling. He sat down again beside the whale on a bundle of kelp and sea grass. A voice startled him.

“I brought you something to eat.”

It was Jesa, that widow known to be crazy with grief, that woman who had beseeched the fishermen to tow the beast out to sea, and failed. She was behind Kin, holding a plate of food.

“I’m not hungry,” he said.

“You’re lying.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“Maldito, don’t you get it? If you want to push the whale back into the sea, you need more strength.”

She gave him the plate. Fish, rice, and beans. He said nothing and ate with his hands.

She had been there for ten minutes, letting the food grow cold, watching this boy. Now she watched him cramming the food into his mouth. He hadn’t eaten all day. Maybe not all week. Skinny as an eel. Stubborn as a roosterfish. Maybe nine or ten years old, she figured. Another street urchin tossed up by the waves. Seen him running errands for those yellowbellied fishermen. Why was he here? Wasn’t he the one who first saw the whale?

He finished the food and gave the plate back without a word.

“You’re welcome!” she said, and walked away, empty plate and unused fork in her hand.

The sun was going under. Kin whispered and stroked the whale’s flanks and thought about life and death. Dead fish washed up every day on the shore, large and small, sometimes fly-ridden, sometimes already shredded to bones. Death was everywhere. But this beast had been so alive. A giant traversing oceans, now reduced to shallow breaths, an expanse of fat and skin.

His thoughts were interrupted by a distant roar. The sound continued but he didn’t see the wave rising, a freak, a massive veil of brine and salt, that drew over the shore like a dark, annihilating curtain.

They called it Nazaré. You heard it before you saw it. It broke the laws of nature. A wave was supposed to make a wide perfect curl like butter from a knife and then collapse on itself and dissipate onto the shore, disappear like a memory. Nazaré rose tight, like a great rearing horse, higher and higher, overwhelming the other elements.

At the last moment, Kin saw the rising tower of water. It wasn’t the tide coming in. It was something sent by the spirits of the ocean, or that’s what the people of Balaal would have said had they seen it. He knew it would sweep over the land and drag everything in its path back out to sea, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...