- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

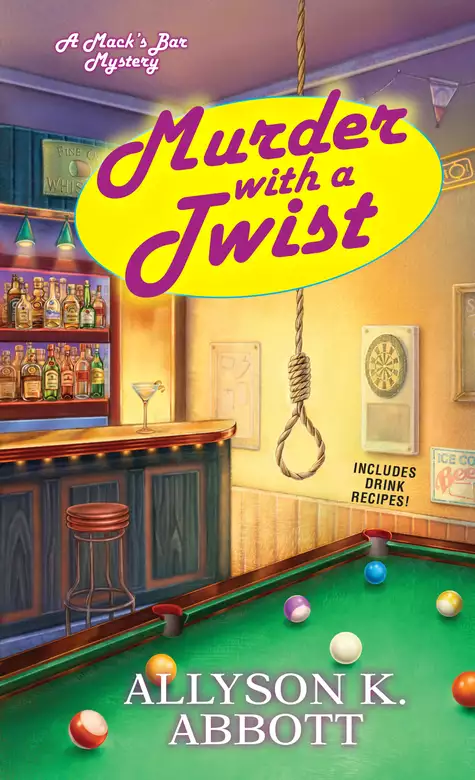

The regulars at Mack's Bar love putting their heads together to solve a good mystery. But Mack is learning there's a big difference between barroom brain teasers and real-life murder . . .

Milwaukee bar owner Mackenzie "Mack" Dalton has a unique neurological condition that gives her extra perceptive senses, and police detective Duncan Albright is convinced Mack's abilities can be used to help catch crooks. Mack may be at pro at mixing drinks, but she's still an amateur when it comes to solving crimes—and she's not sure she should mix business with pleasure by working with a man who stirs up such strong feelings in her. At her first crime scene—a suspicious suicide—she experiences a heady cocktail of mixed sensations and emotions that make her question whether police work is right for her. But when Duncan asks her to help find a kidnapped child, she knows she has to give it a shot . . .

Release date: August 5, 2014

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 335

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder with a Twist

Allyson K. Abbott

The sight made my stomach churn and I wasn’t sure if this was a genuine visceral reaction to what I was seeing, or one of my unique responses. You see, I don’t experience the world the way others do because sometimes my senses don’t make any sense, or rather they make too much sense. Plus they have a tendency to go a little haywire when I feel stress or strong emotion of any kind, and looking at dead people tends to do that to me.

My name is Mackenzie Dalton, though most people just call me Mack. I own and run a bar in downtown Milwaukee, a duty I shared with my father, Big Mack, until his death nearly a year ago. It was a bit of a leap to go from bartending to the scene before me, but oddly enough, I’d been preparing for this moment for several weeks with the help of a Milwaukee detective named Duncan Albright.

I was once told by a sociology professor who came into my bar that the biggest differences between human thought and that of animals are the ability to tell time and an understanding of the permanence of death. Certainly animals resist death when it comes on them, as do most of us humans. But the sociologist claimed that the animals have no understanding of the finality behind it. I understand it all too well because I’ve experienced it firsthand recently with the death of my father and his girlfriend, Ginny, both of whom were murdered. Given that, you might think I would want to avoid death as much as possible now. But I’ve decided this is my way to make a difference in this life because, on most days, I believe this is it. I’ve got one chance to make a mark. And if I’m wrong, I figure the karma can’t hurt.

It all started six weeks ago in early October when I met Duncan Albright for the first time. He was there to investigate the death of a woman whose body I found next to a Dumpster in the alley behind my bar. That woman was Ginny Rifkin, a highly successful local Realtor and my father’s girlfriend at the time of his death. I was the prime suspect in both murders at some point, and it was a combination of police instincts, luck, and my unique ability that kept me out of prison.

My so-called unique ability is actually a neurological disorder called synesthesia, which causes my senses to be cross-wired. As a result I tend to experience things in multiple ways . . . ways that others don’t. For instance I not only smell odors, I may hear or feel them. And I not only hear sounds, I may taste or see them. All of my senses are like this, and Duncan Albright has taken to calling me his personal bloodhound. It does seem as if my senses are not only mixed but heightened, and Duncan, along with a group of my bar patrons, decided my quirk could be put to good use when it came to solving crimes. Over the past few weeks, Duncan focused his efforts on staged crime scenes where he’d set up a room and have me enter it, look around, and then leave. Then he would alter something in the room and have me come back to see if I could detect what the alteration was. At first it was simple things, like a missing item, or an added item, or an item that was moved to a different position. When I passed those tests with flying colors, he moved on to smells. He would spray a tiny amount of perfume somewhere and see if I could pick up on it. After the perfume, he ramped things up a little by simply rubbing an item with one of those scented dryer cloths. Or he would bring a scented candle—unlit—into the room and let it sit for a few minutes before he took it out again. Not only was I able to identify the smell and where it had been the most concentrated, I was able to tell that he had brought something into the room that he had then removed.

Duncan was fairly impressed with these little parlor tricks, but he was truly awed when we started playing around with sounds. He set up several scenarios where he would create some kind of noise in a room in a way that kept me from hearing it. Several times he had me wear headphones with music playing through them—something that triggered a fun display of shapes and colors—and another time he had me go outside while he made the noise in an enclosed restroom in my bar. Upon entering the room, I could typically tell from where the sound had emanated, how loud it had been, and, a few times, I was even able to identify the specific noise because I recognized the associated taste or visual manifestation it triggered as one I had experienced before.

We discovered timing played a role to some degree. The longer it had been since a sound occurred, or since something was moved or removed, the harder it was for me to identify. The time span was longer for smells, and in a way it all made sense when I considered the theory put forth by the neurologist who had finally diagnosed me in my teens, saving me from a cornucopia of psych drugs, or worse, shock treatments and a mini-vacation in a mental institution. His theory was that I was somehow able to detect minute particles of things. So if something is moved or removed, it creates a disturbance in the surrounding air and space that I am able to detect. If a sound is made, it disturbs the air around it and some part of my body is aware of this disruption. For smells, actual molecules of an item may often linger in a place where the smell occurred. That’s why I seem to be able to pick up smells for a longer period of time after the causative item is gone. All humans can do this to some degree, like when people pick up the scent of cigarette smoke on a smoker, or even on someone who hung out with smokers. But my ability seems to be more sensitive than most.

The one I can’t quite make sense of is my ability to detect emotional highs and lows in other people, even when I have never met them and they are no longer around. When I visit places where highly emotional events have occurred, I can sometimes tell. There is an odd visual sensation—like the heat waves one might see in the desert or above a hot tarmac—that clouds my vision. I can still see clearly, thank goodness, but the waves come on my visual field like they do in the ocean.

Some of my customers participated in a few of Duncan’s tests, part of his reassurance that I wasn’t cheating. While I excelled at the parlor trick aspect of things, I haven’t done nearly as well with what Duncan and my customers call deductive reasoning. In an effort to help me in that regard, they started thinking up scenarios for me to analyze. These tests proved far more difficult for me because they were imagined only, hypothetical or historical cases that were relayed to me verbally. Because of this, none of my extra senses proved useful even though they were always active and giving me constant feedback on my current environment. In fact, they often proved to be something of a nuisance. And for some reason, my mind doesn’t seem to want to work in a deductive way. Maybe it’s because I’ve spent so many years trying to shut it, and all the extraneous senses that come with it, down.

Still, I do enjoy my new role despite the fact that it focuses more on death and bad things than on life and good things. I enjoy the challenge of puzzle solving and trying to think outside the box as I apply my unique talent to the art of crime solving. Enjoyment isn’t skill, however, and while I haven’t done well with the deductive reasoning tests, it doesn’t stop me from trying. Plus, it just so happens to be good publicity for my business.

Six weeks ago, Mack’s Bar was featured in the local paper and slapped with the title “the CSI Bar” because of the crimes we’d been able to solve—Ginny’s murder and my father’s—and because of all the cops who now frequent the place. At first it was only Duncan, who was filmed by a TV crew mixing drinks behind the bar, though he was actually working undercover at the time and only a few people knew he was a cop. But other cops who were involved with the investigation discovered that they liked my coffee while on the job, and the bar’s ambience when off the job. Initially, my police clientele were limited to those who worked in Duncan’s district, but the word spread and soon I was seeing off-duty cops from other districts in Milwaukee. It gives me a strong sense of security, because at any given moment, my bar is likely to have a cop in it somewhere.

Shortly after the CSI Bar article, it seemed as if a discussion of some crime or another was going on in the bar at any given time. Newspaper articles were being scoured, TV newscasts were getting dissected, and cops were getting grilled for the inside scoop on crimes of all kinds going on in the city and elsewhere. A core group of folks who participated in the crime discussions dubbed themselves the Capone Club after we learned of a connection between the notorious gangster Al Capone and some of the buildings in the area.

I figured it was a topical, trendy thing that would eventually die down. But when it didn’t after several weeks, I decided to adopt an if–you–can’t–beat–’em–join–’em attitude about the whole thing. I started by creating several new cocktails with catchy crime-solving names and featuring one each night of the week as a special with a discounted price. Mondays have become Fraud Day, so the crime or puzzle of the day has to be something related to fraud, and my cocktail special of the day is a Sneaky Pete, a drink made with an ounce each of a coffee-flavored liqueur and whisky or bourbon, topped off with four ounces of milk or cream and served over ice. Tuesday is Vandalism Day, and Wednesday is Larceny Day. Thursdays are Assault and Battery Day, and the drink du jour is a Sledgehammer, aptly named since it combines two ounces of vodka, two shots of rum, three ounces of Galliano, one ounce of apricot brandy, and two ounces of pineapple juice, served over ice. Fridays and Saturdays are dedicated to homicides or other death-related puzzles, and Sundays are a free-for-all.

Given my theme days, I suppose it’s fitting that it was on a Saturday when Duncan brought me to my first real-life death scene . . . though I was puzzled by something at first. I remember someone saying that it’s against the law to attempt suicide, but not to succeed at it. I suppose that makes sense in a way. I mean, who are you going to convict for a successful suicide? But that made me wonder why Duncan brought me to the hanging man. Because, at first blush it sure looked like a suicide to me, given that there was a tipped-over chair beneath him and a suicide note on the table. And it was also obvious that the victim was successful in his attempt, leaving no one to prosecute for a crime. I didn’t need any special senses to know that he was dead.

But it turns out things aren’t always what they seem and, in this case, the death turned out to be a convictable crime.

There’s another reason why it was ironic to find myself looking at a hanging victim: last night’s test case at the bar had also involved a hanging.

It was a Friday night and I was doing a thriving business. Several of my regular customers were gathered near the bar; they often rearrange the tables and chairs to make one big table they can all sit around. The group included Cora, a forty-something, single, compulsive flirt and computer nerd. She has red hair like me, though hers comes from a bottle, and she owns her own computer troubleshooting company. She and one of her employees are working on a software program that will help analyze crime evidence and suspects—sort of a computerized version of the game Clue—and come up with the name of the most likely culprit. While the software still has a lot of bugs in it, so far it has done slightly better than I have when it comes to solving the proposed cases that come up at the bar, although it still falls far short of any acceptable grade.

Cora is also using her computer skills in another way. She is helping me build a database of my sensory reactions to things, so Duncan and I can consult it anytime I’m unable to recall the connection between one of my synesthetic reactions and a real sense.

Also part of the Friday night group were the Signoriello brothers, Frank and Joe, two seventy-something retired insurance salesmen who are like kindly old uncles to me. I’ve known the brothers my entire life, because my dad and I lived in an apartment above the bar and the brothers have been patronizing the place since before I was born. And, ever since my dad died, they’ve taken on a more active role in watching out for me.

Tad Amundsen, a very attractive man in his late thirties who works as a CPA and financial advisor in an office near my bar, was also part of the group. Tad, like the others, is a regular at my bar, primarily because he is very unhappily married to a wealthy woman he is unwilling to divorce. Consequently, he spends a lot of time in my bar under the guise of working late, often fending off women—and the occasional man—who flirt with him. Tad has movie star looks, and I’m pretty sure his wife, Suzanne Collier, who is eleven years his senior, married him so she could have some eye candy to sport on her arm and escort her to the many functions she attends. Since Suzanne and Tad live in an upscale condo that is within walking distance of my bar, Tad often drops by during nonworking hours, too.

While Cora, Joe, Frank, and Tad are longtime regular customers, I also have a new batch of regulars who have been coming on a steady basis for the past six weeks.

On this particular Friday night, the newer regulars in attendance at the CSI table included two women friends named Holly Martinson and Alicia Maldonado, and their male companions, Sam Warner and Carter Fitzpatrick. Holly and Alicia both work at a nearby bank and have become frequent lunchtime and evening customers. They are good friends and an interesting duo in that they are like the yin and yang of women. Holly is tall, blond, blue eyed, and slender, whereas Alicia is short, heavy, dark skinned, and has brown eyes and hair. Carter, who is Holly’s boyfriend, is also tall and slender, with strawberry blond hair and green eyes. He’s a part-time waiter and wannabe writer who is always working on the next great novel or screenplay. Whenever he comes into the bar, he brings his laptop along, and his standard uniform every time I see him is jeans with a corduroy shirt. So far, he hasn’t managed to sell any of his written works, but that doesn’t keep him from trying, and the CSI angle of my bar intrigues him because he says it keeps his mind churning and thinking up new ideas. Sam Warner is Carter’s friend—the two have known each other since grade school—and a grad student studying psychology with the hope of eventually becoming a practicing psychologist. He, too, is intrigued by the crime-solving aspects of the bar life at Mack’s, and his insight into human nature gives him an edge from time to time.

I suspect Alicia’s primary motivation for coming to the bar stems from the giant crush she has on my bartender, Billy Hughes, who is working to pay his way through law school. She finds endless excuses to talk to Billy, manages to sneak in plenty of supposedly casual touches to his arms and hands, and laces every conversation they share with sexual undertones and innuendo. Unfortunately for Alicia, Billy has a girlfriend named Whitney who he seems to be serious about, which is also unfortunate for him, in my opinion. I don’t like Whitney much. She deems bartending to be a job far beneath Billy’s talents and has made it clear she thinks being in my bar is akin to hanging in the slums. She’s all about appearances, snobbish, and rude, and it’s hard for me to see Billy with her since his personality is the exact opposite. At least he stands up to her and defends both his job and my bar, but I sense that if the relationship continues, Whitney will soon be the one in charge.

I keep hoping Billy will succumb to someone else’s charms and dump Whitney. But aside from the gently flirtatious banter he uses on all the women who come into the bar, Billy, like Tad, never gives Alicia, or anyone else, any hope that her feelings are reciprocated, even though he has plenty of opportunities. With his tall, lanky build, emerald green eyes, and café au lait–colored skin, the man is a looker, and his charming, fun personality round out the package. Despite all the attention he gets, Billy manages to keep his admirers at a safe distance without pissing any of them off. And because he is a law student, he seems to enjoy the crime-solving games as much as anyone. Not only is he good at thinking outside the box, he’s smart enough to figure things out a lot of the time. My goal is to train myself to think more like Billy.

On the flip side of the coin is my cocktail waitress, Missy, the female version of Billy—a lovely girl with silky blond hair, a curvaceous body, huge blue eyes, and milky smooth skin. Men flirt with her all the time, and I have several customers who I know come in to my bar solely to see her. Unfortunately, Missy doesn’t have Billy’s ability to keep her admirers at a safe distance. As a result, she is now a single mother of two and lives with her parents. Missy is very intrigued by the crime games despite her inability to understand the most basic connections and concepts, and on that Friday night before I came face to face with the real hanging man, she was hovering by the tables where the others were sitting, listening when she probably should have been making rounds and taking drink orders.

Unfortunately, Missy isn’t my smartest employee. She’s about as sharp as a bowl of oatmeal, at least when it comes to everyday knowledge and common sense, although she has a savantlike ability to match a face with a drink. If you are someone who orders the same drink most of the time, you’ll only have to tell Missy once. She’ll remember it forever after that. She might not remember your name or anything else about you, but she’ll get that drink order right every time. While I know I should probably get on Missy more about hanging around the crime game folks—something she does every time she works—I often let her get away with it for one simple reason I’m not proud of: Missy’s dim-witted attempts to solve the crimes make my comments and feeble guesses look almost brilliant by comparison.

Since it was a Friday night and therefore a homicide night, the drink special was an Alibi—a vodka-based drink flavored with ginger and lime—which was offered half price to all customers, and free, along with something to eat, to anyone who solved the “crime” for the night. Most of the folks at the CSI table had ordered one in preparation for the night’s crime-solving puzzle.

I smiled when I saw that both of the Signoriello brothers had pens and little notepads just like the one Duncan uses, so they could take notes as Cora talked. The brothers love these little crime-solving sessions, and lately they spend as much time in my bar as they do at home. They are like eager children, which is funny given that they are both in their seventies with salt-and-pepper hair and a lot of well-earned wrinkles.

“To justice,” Cora said, offering up a toast. Everyone clicked glasses and drank. When they were done, Cora kicked off the night’s crime solver. “Here’s our scenario. Listen carefully.

“A woman named Penelope comes home from an overnight visit to her daughter’s and finds her husband, Harry, dead, hanging in the utility room in the basement from a pipe in the ceiling. Harry had been ill with cancer, but according to his wife, he was in full remission and on the mend. The open ceiling in the basement is ten feet high. There is no chair, stool, or anything else in the room that Harry could have stood on, and his feet are dangling a good foot above the floor.

“The noose is fashioned from a long utility-style extension cord, one end of which is around Harry’s neck and tied in the back using a typical hangman’s knot. The other end has been looped over two pipes in the ceiling and is then tied around a floor-to-ceiling beam several feet away. Harry’s hands are secured in front of him with a zip tie and his wrists are slightly bloodied, presumably from his attempts to escape his restraints. The sink in the basement utility room is plugged and the hot water faucet is turned on, resulting in the sink overflowing. There is a drain in the utility room floor, but it has been blocked by an empty plastic kitchen-size trash bag, resulting in three to four inches of standing water in the basement. Some recyclable trash—an empty, half-gallon-size plastic milk carton, the soggy remnants of a large cardboard box, and three plastic containers from some microwaveable meals, all of which are presumed to have come from the trash bag—is floating on top of the water.

“The house has been ransacked and, according to Penelope, there are electronics and jewelry missing, along with some cash from a money jar the couple had. The police investigate and find that the couple is financially drained, as both were self-employed and much of Harry’s cancer treatment was paid for out of pocket. Harry does have life insurance, and the payout doubles for an accidental death. However, a death from his cancer is excluded for a period of five years because he had it at the time he applied for the policy and there are still two years to go before this exclusion expires. Fortunately for the wife, the settlement from the insurance company will be enough to pay off all the debts the couple has incurred and still leave her with a tidy nest egg.

“At first the cops decide poor Harry was the unfortunate victim of a break-in and burglary gone wrong. They surmise that the water in the sink was left running and intentionally allowed to flood to eliminate or compromise any trace evidence. They later begin to wonder if Harry committed suicide, but they can’t figure out how. Since Harry’s hands were secured in front of him, and there was nothing found in the room that he could have stood on in order to hang himself, could Harry have committed suicide, or was he murdered? Go.”

Cora then sat back and smiled at the group. Since the purpose behind these games was for me to try to learn to be more deductive in my reasoning and think like a detective, everyone turned and stared at me. Duncan had recently prepped me by suggesting that I analyze each crime scene with an eye toward motive, means, and opportunity. So I started there.

“Hanging seems like a rather extreme way to kill someone on the spur of the moment,” I said. “So I can see why the cops might have been suspicious. Maybe the killers were sadistic. It does seem like they used stuff that was readily available, so maybe they were surprised by Harry’s presence and had to think on the fly.”

“However,” Sam said, “the apparent randomness of the crime suggests a killer or killers who aren’t very organized in their thinking. Could the wife have strung him up?”

Cora shook her head. “Penelope’s alibi is verified. She was nowhere near the house at the time of the crime. And even though Harry was thin, he was still quite a bit heavier than Penelope.”

“Did Harry have any drugs in his system?” I asked.

“Good question,” Cora said. “As a matter of fact, he did. The coroner found morphine in his blood, but not enough to have killed him. A chat with Harry’s doctor reveals that his cancer had recurred, something he had kept from Penelope, and he had a prescription for morphine that he was taking on a regular basis.”

Carter jumped in then. “Is it possible he committed suicide and staged it to look like a murder?”

“Excellent!” Cora said. “While processing the house, one of the crime scene techs notices a very tiny drop of blood on the broken window of the door, which is assumed to be the mode of entry the burglars used. DNA typing shows that thi. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...