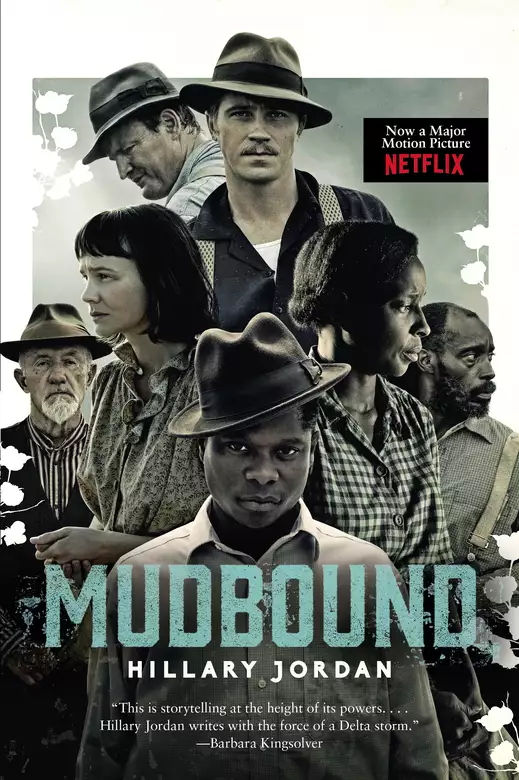

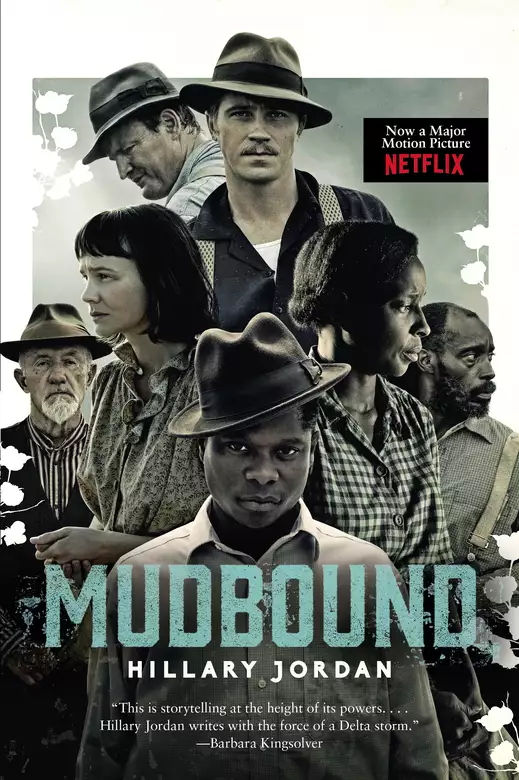

Mudbound

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Hillary Jordan's mesmerizing debut novel won the Bellwether Prize for fiction. A powerful piece of Southern literature, Mudbound takes on prejudice in its myriad forms on a Mississippi Delta farm in 1946. City girl Laura McAllen attempts to raise her family despite questionable decisions made by her husband. Tensions continue to rise when her brother-in-law and the son of a family of sharecroppers both return from WWII as changed men bearing the scars of combat.

Release date: February 28, 2017

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mudbound

Hillary Jordan

“A compelling family tragedy, a confluence of romantic attraction and racial hatred that eventually falls like an avalanche . . . The last third of the book is downright breathless.”

—The Washington Post Book World

“[A] supremely readable debut novel . . . Mudbound is packed with drama. Pick it up, then pass it on.”

—People, Critics Choice, 4-star review

“Mudbound argues for humanity and equality, while highlighting the effects of war . . . [The] mixture of the predictable and the unpredictable will keep readers turning the pages . . . It feels like a classic tragedy, whirling toward a climax. [An] ambitious first novel.”

—The Dallas Morning News

“By the end of the very short first chapter, I was completely hooked . . . [Mudbound is] so carefully considered and so full of weight . . . This is a book in which love and rage cohabit. This is a book that made me cry.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“[A] tremendous gift, a story that challenges the 1950s textbook version of our history and leaves its readers completely in the thrall of her characters . . . Mudbound may well become a staple of syllabi for courses in Southern literature.”

—Paste magazine, 4-star review

“Does an excellent job of capturing the impacts of racism both casual and deliberate.”

—The Denver Post

“[An] impressive first novel . . . Jordan is an author to watch.”

—Rocky Mountain News

“This is storytelling at the height of its powers: the ache of wrongs not yet made right, the fierce attendance of history made as real as rain, as true as this minute. Hillary Jordan writes with the force of a Delta storm. Her characters walked straight out of 1940s Mississippi and into the part of my brain where sympathy and anger and love reside, leaving my heart racing. They are with me still.”

—Barbara Kingsolver

“Is it too early to say, after just one book, that here’s a voice that will echo for years to come? . . . Jordan picks at the scabs of racial inequality that will perhaps never fully heal and brings just enough heartbreak to this intimate, universal tale, just enough suspense, to leave us contemplating how the lives and motives of these vivid characters might have been different.”

—San Antonio Express-News

“This book packs an emotional wallop that will engage adult and adolescent readers . . . The six narrators here have enough time and space to develop a complicated set of relationships. The fault lines among them converge into a crackling gunpoint confrontation, a stunning scene that ranks as my personal favorite of this year.”

—The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Refusing to turn the page is not an option. Jordan is able to make her painful subject matter irresistible by putting the breath of life in these people.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Jordan has an uncanny knack for nailing the voices of characters she has no business knowing, but know them she does. Mudbound also reminds us of the sacrifices made by all soldiers, and how the home front isn’t always as appreciative as it should be.”

—MSNBC.com, Can’t Miss column

“Luminous . . . The power of Mudbound is that the characters speak directly to the reader. And they will stay with you long after you put the book down.”

—Jackson Free Press

“A page-turning read that conveys a serious message without preaching.”

—The Observer (U.K.)

“Mudbound dramatizes the human cost of unthinking hatred . . . That [she] makes a hopeful ending seem possible, after the violence and injustice that precede it, is a tribute to the novel’s voices . . . The characters live in the novel as individuals, black and white, which gives Mudbound its impact.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“If Hillary Jordan’s new book, Mudbound, is ever made into a movie, the odds are very good that it will end up on the short list for an Academy Award. Not just because of the quality of Jordan’s writing . . . but also because she tackles some of this country’s most enduring and well-trodden emotional and historical territory.”

—Albany Times Union

“The recognition [Jordan]’s received for the work has been nothing short of sparkling . . . Mudbound is as much a tale of racism as it is the transcending powers of love and friendship.”

—Austin American-Statesman

“Full of rich details and dimensional, engaging characters, and it sucks readers in like quicksand from its opening scene.”

—Creative Loafing, Atlanta

“[A] heart-rending debut novel . . . Jordan’s beautiful, haunting prose makes it a seductive page-turner.”

—DailyCandy

“A meticulous, moving narrative.”

—Texas Monthly

“Jordan has crafted a story that shines . . . A good historical novel with a twist of an ending.”

—The Oklahoman

“This is one of the most extraordinary novels I’ve read all year . . . Set against the pull of the land—and of the lonely heart—the ensuing tragedy is both inevitable and heart shattering.”

—Dame magazine

“Stunning and disturbing . . . A story of heroism, loyalty, respect and abiding love.”

—Rocky Mount Telegram

“No denying that readers in search of straightforward storytelling will be hooked.”

—Memphis Flyer

“Debut novelist Hillary Jordan has crafted an unforgettable tale of family loyalties, the spiraling after-effects of war and the unfathomable human behavior generated by racism.”

—BookPage

“[A] beautiful debut . . . A superbly rendered depiction of the fury and terror wrought by racism.”

—Publishers Weekly

“[A] poignant and moving debut novel . . . Jordan faultlessly portrays the values of the 1940s as she builds to a stunning conclusion. Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal, starred review

“Mudbound is a real page-turner—a tangle of history, tragedy, and romance powered by guilt, moral indignation, and a near chorus of unstoppable voices.”

—Stewart O’Nan, author of A Prayer for the Dying and Last Night at the Lobster

What inspired you to write Mudbound?

My grandparents had a farm in Lake Village, Arkansas, just after World War II, and I grew up hearing stories about it. It was a primitive place, an unpainted shotgun shack with no electricity, running water, or telephone. They named it Mud-bound because whenever it rained, the roads would flood and they’d be stranded for days.

Though they only lived there for a year, my mother, aunt, and grandmother spoke of the farm often, laughing and shaking their heads by turns, depending on whether the story in question was funny or horrifying. Often they were both, as Southern stories tend to be. I loved listening to them, even the ones I’d heard dozens of times before. They were a peephole into a strange and marvelous world, a world full of contradictions, of terrible beauty. The stories revealed things about my family, especially about my grandmother, who was the heroine of most of them for the simple reason that when calamity struck, my grandfather was inevitably elsewhere.

To my mother and aunt, the year they spent at Mudbound was a grand adventure; and indeed, that was how all their stories portrayed it. It was not until much later that I realized what an ordeal that year must have been for my grandmother—a city-bred woman with two young children—and that, in fact, these were stories of survival.

I began the novel (without knowing I was doing any such thing) in grad school. I had an assignment to write a few pages in the voice of a family member, and I decided to write about the farm from my grandmother’s point of view. But what came out was not a merry adventure story but something darker and more complex. What came out was, “When I think of the farm, I think of mud.”

So, your grandmother’s voice was the one that came to you first as you started writing this?

Yes, hers was the first, and only, voice for some while. My teacher liked what I wrote and encouraged me to continue, and I tried to write a short story. My grandmother became Laura, a fictional character much more fiery and rebellious than she ever was, and the story got longer and longer. At 50 pages I realized I was writing a novel, and that’s when I decided to introduce the other voices. Jamie came next, then Henry, then Florence, then Hap. Ronsel wasn’t even a character until I had about 150 pages! And of course, when he entered the story, he changed its course dramatically.

But you never let Pappy speak.

Nine drafts ago, Pappy actually narrated his own funeral (the two scenes at the beginning and end of the book). And people—namely, my editor and Barbara Kingsolver, who read several drafts of Mudbound and gave me invaluable criticism—just hated hearing from him first, or in fact, at all. Eventually I was persuaded to silence him. The more I thought about those two passages, the more fitting it seemed that Jamie should narrate them.

Still, even without having his own section, it’s clear that Pappy really struck a chord with readers. Why do you think that is?

Yes, people really do seem to hate him! Which is as it should be—he’s pretty detestable. He embodies not just the ugliness of the Jim Crow era but the absolute worst possibilities in ourselves.

What was the hardest part of writing Mudbound?

Getting those voices right—the African American dialect especially. I had a number of well-meaning friends say things to me like, “even Faulkner didn’t write about black people in the first person.” But ultimately I decided I had to let my black characters address the ugliness of that time and place themselves, in their own voices.

Your book takes on racism on many levels—the most obvious forms, but also the more insidious kinds, like the share-cropping system, for example.

In researching this book, I was astounded by what I learned about the perniciousness of the sharecropping system. Owning your own mule meant the difference between share tenancy, in which you got to keep half your crop, and sharecropping, in which you got to keep only a quarter. A quarter of a cotton crop wasn’t nearly enough for a family to live on, so people went further and further into debt with their landlords. And they were so incredibly vulnerable—to misfortune, to illness, to bad weather conditions. Being a sharecropper wasn’t that far removed from being a slave.

The climactic scene with Ronsel is absolutely wrenching to read. I imagine it was equally wrenching to write.

Yes, it was. I’d been unsure for months what was going to happen in that scene. And when it finally came to me, all the hairs on my arms stood up, and I called my best friend James Cañón (who is also an author and was my primary reader during the seven years it took me to write Mudbound), and I said, “I know what’s going to happen to Ronsel,” and I told him. And there was this long silence and then he said, “Wow.”

I dreaded writing the scene, and I put it off for a long time. When I finally made myself do it, I cried a lot. I was reading it out loud as I went—which for me is an essential part of writing dialogue—and having to speak those horrific things made them that much more real and terrible.

What books would you recommend to those who want to know even more about the period?

All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, by Theodore Rosengarten. This is a true first-person account of a black Alabama cotton farmer who started out as a sharecropper and ended up owning his own land, with many adventures along the way. Nate was an indelible character, smart (though illiterate) and funny and wise about people. He was eighty years old when he told his life story to Theodore Rosengarten, a journalist from New York. And what a fascinating life it was.

James Cobb’s The Most Southern Place on Earth.

Pete Daniel’s excellent books Breaking the Land and Deep’n as It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood and Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life in the Twentieth Century.

A PBS series of documentaries about black history from The American Experience.

Clifton L. Taulbert’s When We Were Colored.

And of course, the works of James Baldwin, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, and Richard Wright, among others.

Have you begun working on another novel?

Yes, and it’s absolutely nothing like Mudbound! After seven years of working on it, I was extremely ready to leave the Deep South, the past, and the first person. My second novel, Red, is set in a dystopian America roughly thirty years in the future. It begins in Crawford, Texas, and ends—well, who knows?

1. The setting of the Mississippi Delta is intrinsic to Mudbound. Discuss the ways in which the land functions as a character in the novel and how each of the other characters relates to it.

2. Mudbound is a chorus, told in six different voices. How do the changes in perspective affect your understanding of the story? Are all six voices equally sympathetic? Reliable? Pappy is the only main character who has no narrative voice. Why do you think the author chose not to let him speak?

3. Who gets to speak and who is silent or silenced is a central theme, the silencing of Ronsel being the most literal and brutal example. Discuss the ways in which this theme plays out for the other characters. For instance, how does Laura’s silence about her unhappiness on the farm affect her and her marriage? What are the consequences of Jamie’s inability to speak to his family about the horrors he experienced in the war? How does speaking or not speaking confer power or take it away?

4. The story is narrated by two farmers, two wives and mothers, and two soldiers. Compare and contrast the ways in which these parallel characters, black and white, view and experience the world.

5. What is the significance of the title? In what ways are each of the characters bound—by the land, by circumstance, by tradition, by the law, by their own limitations? How much of this binding is inescapable and how much is self-imposed? Which characters are most successful in freeing themselves from what binds them?

6. All the characters are products of their time and place, and instances of racism in the book run from Pappy’s outright bigotry to Laura’s more subtle prejudice. Would Laura have thought of herself as racist, and if not, why not? How do the racial views of Laura, Jamie, Henry, and Pappy affect your sympathy for them?

7. The novel deals with many thorny issues: racism, sexual politics, infidelity, war. The characters weigh in on these issues, but what about the author? Does she have a discernable perspective, and if so, how does she convey it?

8. We know very early in the book that something terrible is going to befall Ronsel. How does this sense of inevitability affect the story? Jamie makes Ronsel responsible for his own fate, saying, “Maybe that’s cowardly of me, making Ronsel’s the trigger finger.” Is it just cowardice, or is there some truth to what Jamie says? Where would you place the turning point for Ronsel? Who else is complicit in what happens to him, and why?

9. In reflecting on some of the more difficult moral choices made by the characters—Laura’s decision to sleep with Jamie, Ronsel’s decision to abandon Resl and return to America, Jamie’s choice during the lynching scene, Florence’s and Jamie’s separate decisions to murder Pappy—what would you have done in those same situations? Is it even possible to know? Are there some moral positions that are absolute, or should we take into account things like time and place when making Judgments?

10. Why do you think the author chose to have Ronsel address you, the reader, directly at the end of the book? Do you believe he overcomes the formidable obstacles facing him and finds “something like happiness”? If so, why doesn’t the author just say so explicitly? Would a less ambiguous ending have been more or less satisfying?

If James Cañón hadn’t been in my very first workshop at Columbia. If we hadn’t loved each other’s writing, and each other. If he hadn’t read and critiqued every draft of this book, plus countless early drafts of individual chapters, during the years it took me to write it. If he hadn’t encouraged and goaded me, talked me off the ledge a dozen times, made me laugh at myself, inspired me by his example: Mudbound would have been a very different book, and I would be writing these acknowledgments from a nice, padded cell somewhere. Thank you, love, for all that you’ve given me. I could not have had a wiser counselor or a truer friend.

I am also grateful to the following people, organizations and sources:

Jenn Epstein, my dear friend and designated “bad cop,” who was always willing to drop everything and read, and whose tough, incisive critiques were invaluable in shaping the narrative.

Binnie Kirshenbaum and Victoria Redel, whose guidance and enthusiasm got me rolling; Maureen Howard, friend and mentor, who told me I mustn’t be afraid of my book; and the many other members of the Columbia Writing Division faculty who encouraged me.

Chris Parris-Lamb, my extraordinary agent and champion, for seeing what others didn’t; Sarah Burnes and the whole Gernert Company team, for embracing Mudbound so enthusiastically; and Kathy Pories at Algonquin, for believing in the book and being such a thoughtful and sensitive shepherd of it.

Barbara Kingsolver, for her tremendous faith in me and in Mudbound; her help in turning the story into a coherent, compelling narrative; her passionate support of literature of social change; and the generous and much-needed award.

The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the La Napoule Foundation, Fundación Valparaiso and the Stanwood Foundation for Starving Artists, for the gifts of time to write and exquisitely beautiful settings in which to do so; and the Columbia University Writing Division and the American Association of University Women, for their financial assistance.

Julie Currie, for the price of mules in 1946 and other elusive facts; Petra Spielhagen and Dan Renehan, for their assistance with Resl’s broken English; and Sam Hoskins, for lessons in orthopedics.

Theodore Rosengarten’s All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw; Stephen Ambrose’s The Wild Blue; Byron Lane’s Byron’s War: I Never Will Be Young Again; Lou Potter’s Liberators (and the accompanying PBS series); and Joe Wilson’s The 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion in World War II, for helping me put believable flesh on the bones of my sharecroppers, bomber pilot and tankers.

Denise Benou Stires, Michael Caporusso, Pam Cunningham, Gary di Mauro, Charlotte Dixon, Mark Erwin, Marie Fisher, Doug Irving, Robert Lewis, Leslie McCall, Elizabeth Molsen, Katy Rees and Rick Rudik, for their unwavering friendship and belief in me, which sustained me more than any of them will ever know; and Kathryn Windley, for all that and then some.

And finally, my family: Anita Jordan and Michael Fuller; Jan and Jaque Jordan; my brothers, Jared and Erik; and Gay and John Stanek. No author was ever better loved or supported.

HENRY AND I DUG the hole seven feet deep. Any shallower and the corpse was liable to come rising up during the next big flood: Howdy boys! Remember me? The thought of it kept us digging even after the blisters on our palms had burst, re-formed and burst again. Every shovelful was an agony—the old man, getting in his last licks. Still, I was glad of the pain. It shoved away thought and memory.

When the hole got too deep for our shovels to reach bottom, I climbed down into it and kept digging while Henry paced and watched the sky. The soil was so wet from all the rain it was like digging into raw meat. I scraped it off the blade by hand, cursing at the delay. This was the first break we’d had in the weather in three days and could be our last chance for some while to get the body in the ground.

“Better hurry it up,” Henry said.

I looked at the sky. The clouds overhead were the color of ash, but there was a vast black mass of them to the north, and it was headed our way. Fast.

“We’re not gonna make it,” I said.

“We will,” he said.

That was Henry for you: absolutely certain that whatever he wanted to happen would happen. The body would get buried before the storm hit. The weather would dry out in time to resow the cotton. Next year would be a better year. His little brother would never betray him.

I dug faster, wincing with every stroke. I knew I could stop at any time and Henry would take my place without a word of complaint—never mind he had nearly fifty years on his bones to my twenty-nine. Out of pride or stubbornness or both, I kept digging. By the time he said, “All right, my turn,” my muscles were on fire and I was wheezing like an engine full of old gas. When he pulled me up out of the hole, I gritted my teeth so I wouldn’t cry out. My body still ached in a dozen places from all the kicks and blows, but Henry didn’t know about that.

Henry could never know about that.

I knelt by the side of the hole and watched him dig. His face and hands were so caked with mud a passerby might have taken him for a Negro. No doubt I was just as filthy, but in my case the red hair would have given me away. My father’s hair, copper spun so fine women’s fingers itch to run through it. I’ve always hated it. It might as well be a pyre blazing on top of my head, shouting to the world that he’s in me. Shouting it to me every time I look in the mirror.

Around four feet, Henry’s blade hit something hard.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Piece of rock, I think.”

But it wasn’t rock, it was bone—a human skull, missing a big chunk in back. “Damn,” Henry said, holding it up to the light.

“What do we do now?”

“I don’t know.”

We both looked to the north. The black was growing, eating up the sky.

“We can’t start over,” I said. “It could be days before the rain lets up again.”

“I don’t like it,” Henry said. “It’s not right.”

He kept digging anyway, using his hands, passing the bones up to me as he unearthed them: ribs, arms, pelvis. When he got to the lower legs, there was a clink of metal. He held up a tibia and I saw the crude, rusted iron shackle encircling the bone. A broken chain dangled from it.

“Jesus Christ,” Henry said. “This is a slave’s grave.”

“You don’t know that.”

He picked up the broken skull. “See here? He was shot in the head. Must’ve been a runaway.” Henry shook his head. “That settles it.”

“Settles what?”

“We can’t bury our father in a nigger’s grave,” Henry said. “There’s nothing he’d have hated more. Now help me out of here.” He extended one grimy hand.

“It could have been an escaped convict,” I said. “A white man.” It could have been, but I was betting it wasn’t. Henry hesitated, and I said, “The penitentiary’s what, just six or seven miles from here?”

“More li. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...