- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

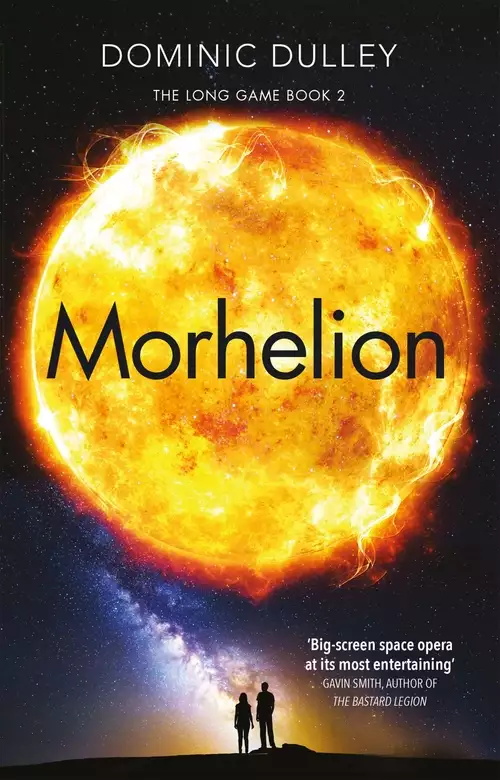

Synopsis

An alien exile. A lethal secret. The hunt is on . . . Orry Kent may not have stopped the war between the Ascendancy and the alien Kadiran, but at least she saved the Grand Fleet from annihilation. Now she just wants to get on with her own life - until a con turns sour and a dying agent of the emperor's Seventh Secretariat tells Orry there's a traitor at the highest levels of the Ascendancy. Which is why she finds herself stranded among the floating bubble habitats of Morhelion, searching for a Kadiran exile who has information critical to the war effort - and the survival of the Ascendancy itself. 'A satisfyingly convoluted plot that sorts out a lot of loose ends but leaves more things lined up for a further book. It's a great read for fans of space opera and criminal capers' SF Crowsnest

Release date: April 4, 2019

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Morhelion

Dominic Dulley

Gyre

‘Hand me that bypass clip, will you?’ Mender said, intent on the partially disassembled scrubber in front of him.

Orry Kent regarded the unfamiliar equipment spread across the table in the farm’s kitchen module with dismay. Her father had taught her a lot of things, but bomb-making wasn’t one of them.

‘Come on, come on,’ Mender muttered, flapping his hand.

‘Um . . .’ Her fingers hovered over a short band of curved metal before she changed her mind and offered the old man a length of coiled wire.

He didn’t look up as he took it and tried to attach it to the scrubber – then he frowned and peered at the object in his hand. Sighing, he rummaged through the junkyard on the table. ‘This,’ he growled, holding up a short cable, ‘is a bypass clip.’

He connected the cable, then returned his attention to a set of schematics displayed on the databrane spread out beside him. The scrubber was a squat cylinder, one of several Dainty Jane used in her life-support systems. The old ship could easily spare it – she was rated for a crew of twenty, and with just Mender, Orry and her fifteen-year-old brother Ethan living aboard, there was a lot of surplus capacity.

Don’t forget to isolate the exchangers, the ship sent over the common integuary channel. She had set down a few hundred metres away, well clear of the network of plastic growing tunnels that surrounded the farm’s hab modules.

I know what I’m doing, Mender sent back, and Orry smiled at her integuary’s precise rendering of his long-suffering tone inside her head. He manipulated the schematic with a gesture, located an access panel on the side of the scrubber and picked up a long probe.

As he inserted it into the casing, Jane reminded him, You need to drain the residual charge from the capacitors.

His hand paused. Do you want to do it?

Just trying to help.

Well, don’t. The probing resumed.

Give it a rest, you two, Orry subvocalised. You’re bickering like an old married couple. She stood behind Mender and rested her hands on his shoulders as she peered inside the scrubber.

‘What are you doing?’ he grunted.

‘Just watching.’

‘Go and watch something else.’

She made a face at the back of his head, then wandered over to one of the worktops that ran around the curving walls, idly fiddling with the stainless-steel utensils sticking out of brightly painted ceramic pots. Everything on the farm was well used, but it was clear the unknown residents took pride in their few possessions. A bowl of colourful rock fragments the size of little sweet tomatoes caught her eye and she picked one up. It was porous, lighter than she’d expected, and shot through with tiny crystals that sparkled like miniature prisms as the light struck them.

‘I wouldn’t touch that,’ Mender said from the table.

‘Why, what is it?’

‘Scorite.’

She looked at the chunk of rock with interest. This job couldn’t succeed without scorite, but she’d never seen the mineral before. ‘It’s pretty,’ she said.

Mender rose from the table with a grunt and stretched, working out the kinks in his back before limping over and taking the scorite from her. When he held it up to the light, spots of reflected colour danced in his artificial eye.

‘You know why this stuff is so valuable?’ he asked, then before she could answer he whipped round and hurled the fragment at the far wall. It struck with a sharp crack and ignited instantly, flashing into incandescence as it dropped to the floor, burning with a white light so intense that Orry had to look away, afterimages ghosting her vision. A smell of melting plastic and scorched metal filled the module and she began to worry that the stuff might burn clean through the floor. When the flame did finally sputter and die, it left a nugget of glowing slag in a circle of melted floor covering and blackened metal.

‘Very dramatic,’ she coughed, waving smoke from her face.

‘There’s a lot of energy bound up in those rocks,’ Mender said, obviously pleased with himself. ‘It’s a delicate business, digging out the stuff without losing some part of you you’d rather keep attached.’

She stared at the scorch mark, thinking of the vast strip-mines that scarred Gyre’s barren surface. Outside of a few larger settlements like Charter City the place was all open-cast mines and agro-stations like this one.

Mender returned to the table and Orry checked the local time. Still hours to go. She needed something to keep her hands occupied.

‘Anything I can do to help?’

He pointed at a plastic tub full of small sachets. ‘You can start emptying that lot into a bowl.’

She examined one of the packets curiously. ‘Desalination crystals?’

‘Hope so – I bought a hundred of ’em. Now do me a favour and shut the hell up. I need to crack this bloody thing.’

She found a suitable bowl under the sink and began tearing open the sachets and pouring out the crystals. By the time she was done, Mender had got the scrubber’s casing open and extracted an oval reservoir of viscous liquid.

‘Put these on,’ he said, handing her a pair of gauntlets.

She wrinkled her nose at the acrid smell as Mender carefully emptied the gelatinous contents of the reservoir into the bowl of crystals and stirred it gently with a metal spoon.

‘Baggies,’ he said, snapping his fingers.

‘Shouldn’t we be wearing respirators?’ she asked as she picked up the roll of self-sealing food bags on the table, tore off the first one and held it open beside the bowl. The smell was lining the back of her throat now, leaving a viscid residue.

Ignoring her, he spooned half the contents of the bowl into the bag.

You’ll be fine as long as it doesn’t touch your skin, sent Jane.

Orry sealed the bag and laid it carefully on the table before tearing off another. Once it was filled, Mender set the bowl and the remains of the scrubber aside and cleared a space for the spherical object he pulled from his pocket. It was painted with yellow and black warning stripes and covered with danger symbols.

‘A mining charge?’ she said, alarmed.

‘Uh-huh,’ he grunted. He reached for a roll of tape, bit off a length and secured one of the baggies around half the charge.

‘Isn’t that a little powerful?’ she asked.

‘Nope.’ He reached for the second baggie.

‘Lefevre isn’t going to buy a hole in the ground.’

‘Relax, girl. I know what I’m doing. Do you?’

She looked sharply at him. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Just that we’ve been on this rock for three weeks and this con of yours has burned through all but the last of our cash.’

She hesitated, suddenly very aware of the bulge in the small of her back, concealed by her coat. ‘It’ll work,’ she assured him.

‘It had better. You wouldn’t like me when I’m starving to death. I get tetchy.’

She folded her arms. ‘I don’t like you now.’

He chuckled and turned the charge over in his hands, examining it carefully, before rising to his feet. ‘Coming?’

‘Right behind you.’ She checked the time again, resisting the urge to get an update from Ethan; her brother wouldn’t thank her for pestering him.

She was still fastening her jacket as Mender left the hab. The moment he was gone she reached behind her and pulled out the package. When she opened the door of the unit she’d chosen and saw the near-empty shelves she felt better about what she was doing, even if she was keeping it from Mender. She pushed the package onto the top shelf, then hesitated. What if things did go wrong? Did she really have the right to do this? She really wished her father was there. What would he do? she asked herself, then realised the answer was obvious: Eoin had always made sure the mark was the only one who suffered.

She closed the cupboard door, looked regretfully at the circle burned into the floor, then raised her hood and followed Mender outside.

*

Gyre’s sky was the colour of amber, its distant sun made hazy by the dust high in the thick atmosphere. It was everywhere, a by-product of the constant mining that made the place taste like burnt coffee and coated the curve of Dainty Jane’s hull as she towered like the shell of a vast crustacean above the farm’s growing tunnels. On the horizon a range of high peaks were blanketed in snow discoloured by the weird amber light.

Gyre was a small moon, which meant low gravity. Orry shrank deeper into her coat as she stepped carefully across the frozen ground.

‘I’ve been asking around,’ Mender said as she caught him up.

‘About what?’

‘You hear about the local firm?’

‘Yeah, Uri told me about them. Don’t worry – there’s no reason for them to find out what we’re doing here, so there’s no point getting involved with them. We’ll be gone in a couple of days.’

‘Did you know they kick back to Roag?’ His breath was steaming in the bitter air.

She tried to ignore the spike of hate the name drove through her chest. ‘I didn’t, but it doesn’t surprise me; that bitch has her claws into everything. All the more reason not to get involved.’

‘So this job has nothing to do with revenge?’

‘In case you hadn’t noticed, the Ascendancy is at war and Cordelia Roag started it. She’s the most wanted person in human space, which makes her kind of difficult to locate. When I’m ready to settle things with her, you’ll be the first to know. What we’re doing here is purely business.’

‘You expect me to believe that? She killed your old man.’

Orry stopped walking. ‘You still don’t trust me,’ she said accusingly. ‘After all that’s happened.’

He held her gaze, then spat on the frozen ground and stomped away, muttering.

Of course he trusts you, Jane told her on a private channel. He’s just nervous.

Orry snorted. That old bastard doesn’t have nerves. She set off after him. Nervous about what? she asked as they approached the ramp down to the cavern.

We were alone a long time, he and I. He’s used to calling the shots. Having you running things for a change is difficult for him.

Orry stared at Mender’s back as he limped down the steep slope ahead of her. Perhaps she had been a little blunt with him – but putting this job together had taken a lot of effort. She’d never really realised how much Dad used to do behind the scenes; no wonder he’d always been grumpy in the run-up to a grift. Blinking hard at the memories, she followed Mender into the cave beneath the farm.

Gyre was riddled with caverns like this one. The voids made mining difficult, but the rewards were worth the risks. Scorite was vital to the starship industry and since the Kadiran attack on Tyr, the Ascendancy needed as much of the stuff as it could get to bolster the Grand Fleet.

Switching her integuary to low-light mode, she saw Mender fixing the mining charge to the end of a long cable dangling from the roof, suspending their homemade bomb at head height. As she looked at the size of the cavern she had to admit that his choice of the charge was probably a wise one; it would need a considerable blast to do the job.

The old man stepped back and looked up at the rough ceiling metres above his head. ‘That should cover it nicely.’ He looked at her. ‘You want to blow it?’

She frowned. ‘You’re sure this will work? How can goop from a scrubber and some desalination powder fool a sniffer?’

‘The chemical signature’s identical to scorite,’ he assured her. ‘It’ll work.’

She chewed her lower lip, not entirely convinced.

‘All right,’ she said eventually, ‘give me the detonator.’

2

Villanueva ’28

Ethan had chosen the alleyway carefully. He and Uri waited in the frigid air a short distance from the main street like actors in the wings. Is this how it feels before going on stage? he wondered as his stomach churned with nervous anticipation.

Five seconds, Orry broke into his thoughts. Four, three, two . . . and go!

He handed Uri the gilt chip, wondering if he would ever see it again. The man wouldn’t have been his first choice, but beggars couldn’t be choosers when seeking out grifters in a strange town.

‘Hey!’ Ethan yelled as the other man took off as planned, heading towards the street. He gave Uri a couple of seconds’ head-start, then set off in pursuit just as the banker, Simon Lefevre, passed the alley’s entrance. ‘Stop him!’ Ethan shouted.

Uri cannoned into the startled banker – and dropped the gilt chip at his feet. Lefevre stumbled back, but before he could say anything Uri was gone, bounding away down the salted pavement in an ungainly low-gravity lope.

Ethan ran into the street, cursing, and skidded to a halt by Lefevre as he stooped to pick up the chip. He let his mouth drop open at the sight of it.

‘You stopped him!’ Ethan said, taking the chip from the banker’s unresisting hand and pressing a button on the side. Beaming, he showed the balance to Lefevre. ‘It’s all here,’ he exclaimed with relief. ‘Thank you!’

The banker raised his eyebrows. ‘That’s a lot of money.’

Ethan laughed and clapped him on the shoulder. ‘You have no idea how important this is. Thank you, so much!’ he repeated.

‘If it’s that important, perhaps you should be more careful with it.’ Lefevre peered down the street after Uri. ‘Did he mug you?’

‘Pickpocketed, actually,’ Ethan explained. ‘I felt something, but he was away before I could grab him.’ He reached out and pumped Lefevre’s hand. ‘I don’t know how I can thank you.’

‘It was nothing, really.’ The banker disengaged with difficulty, looking uncomfortable.

‘Nothing!’ Reaching into his jacket, Ethan pulled out Mender’s empty hipflask, put it to his lips and grimaced. He upturned it, shaking his head sadly. ‘At least you’ll let me buy you a drink?’

‘Aren’t you a little young to be drinking?’

‘I’m old enough,’ Ethan protested, looking around. One of the reasons for selecting this particular alley was the Ruuz-style champagne bar across the street. He could see Lefevre’s interest spark when he followed Ethan’s gaze. ‘Well, I’m having one, anyway,’ Ethan said. ‘I think I might be in shock.’

The banker checked the time and smiled. ‘Why not?’

Got him, Ethan reported as they crossed the street.

The bar was a better-than-average rim world rip-off of an upmarket Fountainhead drinking establishment; the décor wasn’t bad, for a start. And Lefevre was clearly pleased when Ethan ordered a decent bottle.

He paid cash, using the last of their local currency. This had better work, he thought, plastering a smile onto his face to hide his concern. ‘We haven’t been introduced,’ he said cheerily. ‘I’m Abram.’

‘Simon Lefevre.’

The banker was a big man who looked like he’d been in shape once but was now running to fat. His curly hair was slicked back with too much product and he sported a pencil-thin beard in a futile attempt to re-establish his jawline.

He leered at the pretty waitress who brought their champagne over. ‘What time do you get off?’ he asked as she opened the bottle with a muted pop.

She smiled uncomfortably. ‘Would you like me to pour?’ she asked.

‘That’s not all I’d like you to do, sweetheart.’

Ethan felt desperately sorry for the poor girl as he watched her fill two glass flutes; she recoiled when Lefevre reached out to caress the bare skin of her arm.

‘Will that be all?’ she asked stiffly, putting the bottle down.

‘For now.’ He stared at her legs as she returned to the bar, then rolled his eyes lasciviously at Ethan. ‘That,’ he pronounced, ‘should not be allowed.’

Arsehole, Ethan thought as he raised his champagne and grinned. ‘I’ll drink to that!’ He drained half his glass, then grimaced.

‘Something wrong?’ Lefevre asked.

‘Not really,’ he replied, aiming for weary nonchalance. ‘I’m just looking forward to getting back to somewhere I can get a decent drink.’

The banker sniffed his glass and tasted the contents. ‘Tastes all right to me.’

‘It’s fine, I suppose. The Villanueva ’28 just doesn’t travel well. You should taste it on Tyr.’

‘You’ve been to Tyr?’ Lefevre sounded interested.

‘I was born there.’

‘Really?’ The banker looked at him a little doubtfully. ‘What brought you here?’

‘My father.’ Ethan finished his glass, trusting the alcohol inhibitors he’d taken to keep a clear head. Allowing a slight slur to enter his voice, he continued, ‘He invested heavily in Ghent-Masson, then when things started to go badly he dragged us all out here so he could oversee the mining operations personally. It didn’t work, and the company went belly-up.’

‘What did he do?’

Ethan stared into his empty glass. ‘He put a laser in his mouth and pulled the trigger. I was eight.’

‘Rama – that’s tough.’

‘He left us with nothing but the family name, and what’s that worth out here? Marta – she’s my sister – had to take a job to support us. A job!’

Lefevre topped up Ethan’s glass. ‘What is your family name, if you don’t mind me asking?’

‘Grekov. It’s a minor house, but we’re a cadet branch of House Marquardt. Not that those bastards lifted a finger to help.’

‘Why not?’

‘Father’s investments were vulgar, they said, bourgeois. They were glad when he came out here; not so embarrassing for them.’

Lefevre looked sympathetic.

On the hook, Ethan thought happily. He took another gulp. ‘We’ll show them though, when we go back to Tyr with a fortune.’

‘Two thousand imperials is hardly a fortune.’

Ethan waved the gilt chip dismissively. ‘I’m not talking about this. Anyway, drink up and have another – without you, we wouldn’t be going anywhere.’

‘Glad I could be of some small assistance.’ The banker drank, watching him curiously.

‘Damn it all, but I wish I could thank you properly.’ Ethan put his glass down with some force. ‘Honour means everything to a Grekov.’

‘Perhaps you could spare some of that fortune you mentioned,’ Lefevre suggested lightly.

‘You’re right,’ he said decisively.

‘I am?’

‘I should give you a reward.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes, yes – and I know just how I can. What are you doing right now?’

‘Well, I have a meeting—’

‘Cancel it.’

‘Why should I do that?’

Ethan finished his drink. ‘I can’t give you anything now, but if you can spare me half an hour I’ll show you just how generous a Grekov can be.’

The banker narrowed his eyes. ‘How?’

Ethan smiled. ‘Come with me and find out.’

He held his breath as Lefevre considered. Eventually the man smiled and shook his head as if he couldn’t quite believe what he was doing.

‘All right then, my lordling. Where are we going?’

3

Harper’s Pulled Out

While ostensibly an Ascendancy colony, Gyre was owned and governed by the Empyrean Development Company. Clearly quality of life for the miners and the farmers who supported them wasn’t high on EDC’s list of priorities, Orry thought, looking at the Brutalist architecture of Charter City. The land registry office on Tenth Street she was waiting outside was a case in point: the block was the same reddish-brown local rock as every other structure in the city, apparently the only raw material available to the construction printers.

The street was almost empty, even at noon; the cold and dust did not provide a conducive environment for a lunchtime stroll. She’d been on worse worlds, but not many. Spotting Ethan approaching in conversation with the mark, dead on time, she took a breath and prepared herself.

‘Who the fuck is this?’ she demanded before her brother could open his mouth.

Ethan looked genuinely surprised. ‘Simon Lefevre . . .’ he began formally, ‘may I present my sister, Lady Marta Grekov. I’d like to say she’s not always this rude, but that would be a lie.’

Lefevre sized her up, taking in the poor condition of the padded jacket over her thermal coveralls. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I should probably go.’

‘Yes,’ she agreed with feeling, ‘you should.’

‘No,’ Ethan said, ‘this man has done our House a great service. Without him we wouldn’t have enough.’ He held up the gilt chip.

She grabbed him by the arm and dragged him aside. ‘Are you insane?’ she hissed, just loud enough for Lefevre to overhear. ‘Who the hell is he?’

‘He’s all right. He saved me.’

She glared at him. ‘What happened?’

‘I was attacked by a street tough – Simon put his own life at risk to recover our investment.’

Orry thought he was hamming it up a little, but Lefevre didn’t appear to notice anything suspicious. He probably just thought Ethan was drunk.

‘Have you been drinking?’ she asked.

‘No. Well, a little.’ Ethan waved it off. ‘The point is, our House owes this man an honour debt.’

‘Our House?’ Orry snorted. ‘There is no House. Just us, and this.’ She held up her own chip, loaded with all that was left of their gilt.

He stiffened. ‘I don’t care what you say. I am going to pay our debt to this man.’

‘What if he’s’ – she glanced at Lefevre and lowered her voice a little more, just audible to straining ears – ‘in the Corps?’

Ethan snorted. ‘Hey, Simon, are you an arbiter?’

‘What? No! I told you, I work for a bank.’

‘There you are,’ her brother said triumphantly. ‘If he was an arbiter he’d tell us. They have to, you know, or it’s entrapment or something.’

‘Will you shut up—’

‘He’s a good guy,’ Ethan interrupted. ‘I’ll vouch for him.’

‘You don’t even know him.’

‘I’m a good judge of character. Besides, he saved me and we owe him. Look, I’m just going to give him a bit of my share, okay? It’s my money. I still care about our family honour, even if you don’t.’ He shook his head. ‘Look at us: what have we let ourselves become? If we don’t pay an honour debt, this place has beaten us. Is that what you want?’

She glared at him, thoroughly enjoying herself. It felt good to be back in the game. ‘Fine,’ she said eventually, ‘you can do what you like with your share. But if we end up in a Company gaol, it’s on you.’

‘We won’t – I promise.’

She held out a hand for his chip and saw Lefevre sidle closer, curious, as she transferred Ethan’s two thousand to her own chip. His face changed when he glimpsed the balance.

‘Twenty thousand imperials? I thought you were destitute?’

‘It’s taken years to raise that much,’ Ethan told him.

‘What are you going to do with it?’

‘Mind your own business,’ Orry snapped. ‘I’ll be back in a minute.’

She walked into the registry building and spent a few minutes studying the claim maps on the walls. The bleak and soulless interior matched the outside. A clerk watched from behind a counter.

‘Can I help you?’ he asked eventually.

‘No thanks.’ She pulled out the databrane Ethan had prepared for her and strode back out to the street.

‘Did you get it?’ her brother asked.

She grinned and held up the brane. He whooped and gave her a high-five.

‘Is that a land deed?’ Lefevre asked. He was edgy now, but Orry could tell he was intrigued. An honest man would have made his excuses and left at this point, but Simon Lefevre was not an honest man.

‘Never mind what it is,’ she said.

‘Not long now,’ Ethan reassured him. ‘Just a quick walk over the street.’ He led the way into the lobby of a mid-scale hotel used by visiting managers and mining company execs.

Uri? Orry sent. All set?

Yeah, all ready for you.

Good. We’re on our way up now.

In the lift she could tell the banker’s nerves were getting the better of him, but reassuring him was not her job. She was about to give Ethan a mental nudge when he piped up, ‘Do you remember that place we stayed at on Halcyon? I was only, what, five? I still remember it. Better than this shithole. Have you ever been to Halcyon?’ he asked Lefevre, who shook his head. ‘Amazing place. We’ll have to go back there, Sis. After . . . you know.’

She gave a non-committal grunt, pleased with him, and the doors opened.

Uri was barely recognisable when they entered the room Orry had sweet-talked the concierge into letting her rent for a couple of hours. He might be a short-con merchant but there was no doubt the man had a talent for disguise, she reflected. There was no way Lefevre would recognise this smooth, booted and suited executive as Ethan’s shabby pickpocket.

The suite was comfortable, with a view over the city’s industrial sprawl. A metal case rested on a ceramic-topped coffee table.

There were no introductions, no pleasantries. ‘Do you have it?’ Uri asked peremptorily and Orry pulled out the forged deed and handed it to him.

‘And the survey results?’

She produced a second databrane and he studied the two carefully. ‘Well, this all looks satisfactory,’ he said at last, rolling up both branes and slipping them into his pocket. He bent to open the case on the table and she could feel Lefevre’s tension when he saw the layers of currency. ‘Sixty thousand imperials, as agreed,’ Uri said. ‘Would you like to count it?’

Bottom row, third from the left. She picked up the only stack not padded out with blank sheets, held it up and examined it, then riffled through it before replacing it and closing the case. ‘That won’t be necessary. Thank you.’

‘No, thank you,’ Uri said, moving to the door. ‘The suite is booked for the night if you want to make use of it. The account has been settled in advance. Good day.’

Ethan waited for him to leave before clapping his hands and running to the table. He hugged Orry, then opened the case and stared at the money.

‘What just happened?’ Lefevre asked.

She picked up the bundle of genuine notes and counted out six thousand imperials, which she handed to Ethan.

‘Four thousand profit,’ he said. ‘Not bad for ten minutes’ work.’ He peeled off ten hundred-imperial notes and handed them to Lefevre, who stared dumbly at them. Orry could almost see the cogs turning in his head. ‘I told you honour is everything to a Grekov,’ Ethan told him, grinning broadly.

‘You’re giving him a grand?’ she objected.

‘So? Relax, Marta; tomorrow we’ll be spending more than that on breakfast.’

She shot him an angry look that Lefevre must surely interpret as an instruction to shut the hell up, walked to the door and opened it. Now, Uri, she sent. ‘It was nice meeting you, Mr Lefevre,’ she said aloud, ‘and I thank you for your service to my brother, but I’m sure you’re a busy man.’

The phone she’d lifted earlier that day rang. Still holding the door open, she took it out and thumbed it on. ‘Marta Grekov.’

‘Good luck,’ Uri said, and rang off.

‘You’re fucking kidding me,’ she said into the dead phone. ‘The deal is set for tomorrow.’ She waved Lefevre impatiently towards the open door and walked away from him. ‘Where the hell am I supposed to find someone in twelve hours? No, I can’t, you idiot. I’m not a damned cash dispenser.’

The banker was still loitering by the door. Good.

‘Let me explain this one more time, as simply as I can.’ Her voice was getting icier by the second. ‘It has to be tomorrow or the old man will put the place up for auction. So no, I think that attitude is less than helpful. Fuck you, too.’

She hurled the phone across the room, then rounded on her brother. ‘Harper’s pulled out.’

‘Oh shit – so what do we do now?’ He sounded panicky. Perfect.

It took a moment, but eventually Lefevre cleared his throat. ‘Uh, why don’t you tell me what’s going on?’ He stepped away from the door and closed it. ‘Perhaps I can help?’

4

Scorite Seams

‘You said you’re a banker?’ Orry waved Lefevre to a sofa and started pacing the room. ‘How much do you know about scorite?’

‘A bit.’

She studied him for a moment, as if deciding whether or not he could be trusted. ‘Well, I work’ – she loaded the word with disgust – ‘as a mineral surveyor for the local factor’s office, which means I spend my life driving around this shithole of a moon looking for scorite seams. When I find one, I report its location, and for that I receive a modest finder’s fee, then the factor auctions the land rights to the highest bidder. Generally, it goes for tens of thousands of imperials.

‘The Company treats me like crap and the money I get isn’t enough to support one Grekov, let alone two of us, so I decided there must be a better way. Two years ago, when I found a small deposit under some unclaimed land, I borrowed enough cash to purchase the plot myself and found someone – the man who just left – to buy the claim from me. Doing the deal direct meant he paid a fraction of what it would have cost at auction, while I trebled my investment.’

‘Who is he?’ Lefevre asked, but Orry was already shaking her head.

‘Not something you need to know, Mr – Lefevre, was it? I’ll just say he works for an interested party.’

‘You mean for one of the mining concerns.’

She ignored him and went on, ‘I have been exceptionally careful to stay under the radar, building my nest-egg and waiting for the big one – which I found a week ago.’ She gave him a glowing smile. ‘It’s the richest vein I’ve ever seen – you should see the spectrometry results. The sniffer practically blew a fuse. This deposit will be worth millions.’

He looked

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...