- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

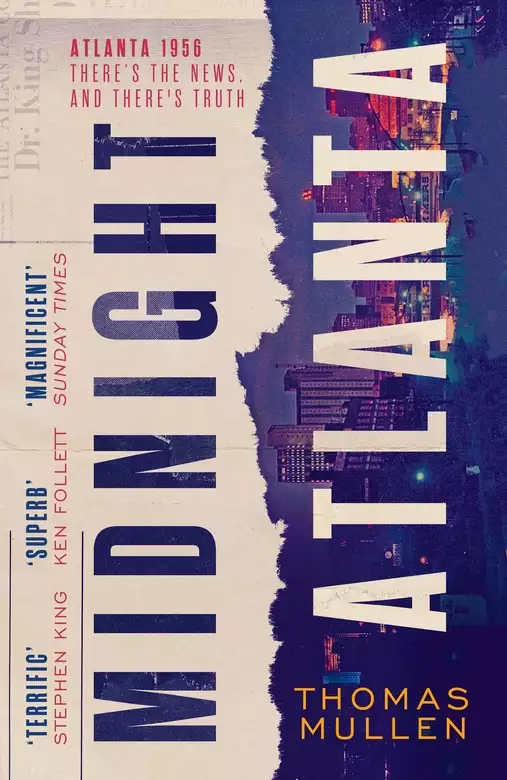

Midnight Atlanta is the stunning new novel in the award-nominated, critically acclaimed Darktown series, and sees a newspaper editor murdered against the backdrop of Rosa Parks' protest and Martin Luther King Jnr's emergence.

Atlanta, 1956.

When Arthur Bishop, editor of Atlanta's leading black newspaper, is killed in his office, cop-turned-journalist Tommy Smith finds himself in the crosshairs of the racist cops he's been trying to avoid. To clear his name, he needs to learn more about the dangerous story Bishop had been working on.

Meanwhile, Smith's ex-partner Lucius Boggs and white sergeant Joe McInnis - the only white cop in the black precinct - find themselves caught between meddling federal agents, racist detectives, and Communist activists as they try to solve the murder.

With a young Rev. Martin Luther King Jnr making headlines of his own, and tensions in the city growing, Boggs and Smith find themselves back on the same side in a hunt for the truth that will put them both at risk.

PRAISE FOR THE DARKTOWN SERIES

'A brilliant blending of crime, mystery, and American history. Terrific entertainment'

Stephen King

'Superb'

Ken Follett

'Magnificent and shocking'

Sunday Times

'Written with a ferocious passion that'll knock the wind out of you'

New York Times

Release date: July 2, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Midnight Atlanta

Thomas Mullen

He did not like perpetuating this cruelty.

Yet as a crime reporter for the Atlanta Daily Times, the only Negro daily in America, it was his job to report facts and meld them into stories, to form some coherent narrative out of the flotsam and randomness of life.

And this is a story that starts with a body.

The shot woke him up.

Or was there a second shot? Smith would wonder that, later, when he wished he had been awake already, when he wished he could travel through time and better experience a moment he had missed, a moment that despite his lack of participation would turn out to be one of the most important in his life. And him slumped there in his chair, a flask in his lap.

His head felt fuzzy from sleep and drink, his limbs so very heavy.

He thought he heard a shout, maybe. Then a crash, definitely.

It took him a second or three, but the solidness that had prevented his arms and legs from moving finally turned liquid and he sprang up. The hell was that?

Footsteps, above. But he lived on the top floor.

Wait, where was he?

In his office, that’s right. He’d had a short date with Patrice, only one drink, then he’d walked her to her meeting at the Oddfellows Building. He’d leaned in for a kiss, which she’d granted, a short peck but with a winning smile that held such promise that he only felt slightly insulted she wasn’t going to skip some dull business meeting for more time with him. Too excited to go home, he’d come to the office to pour himself another drink and type a few pages of a longer piece he’d been tinkering with. He’d thought he’d been alone in the building, but then Mr. Bishop had dropped by and they’d chatted, hadn’t they? Then Bishop had returned to his office upstairs, and Smith had tried again to write. Apparently, the prose hadn’t flowed as well as the bourbon, because he’d fallen asleep at his desk.

He called out the name of his boss, whose office was upstairs: “Mr. Bishop?”

Silence for a few seconds. The footsteps had stopped.

He tried to turn on his desk lamp but found that the bulb had burned out.

Think. That had definitely been a shot, a pistol. He knew the sound well. He hadn’t dreamed it or imagined it. He wasn’t in France, slowly trudging across Europe, and he wasn’t walking his old police beat with Boggs at his side. He was here in his office, late at night. A place guns did not typically go off.

He stepped out of his office. The hallway light was on, the other offices dark. He crept down a perpetually messy hallway, ever crowded with stacks of papers. He reached the stairs to the second floor.

“Who’s up there?” he demanded in the Officer Voice he hadn’t deployed in so long. Deep and commanding, willing to brook no dissent. Loud enough to shake the framed articles on the walls and cause any ne’er-do-well to question the direction his life had taken. The Officer Voice could be surprisingly effective. But when Smith had used it in his old life, he’d had a sidearm and a club on his belt, and a partner beside him.

Footsteps again, quick and heavy. Someone upstairs did not like the Officer Voice.

Smith stepped into his colleague Jeremy Toon’s office, remembering that Toon, a baseball fan, kept a Louisville Slugger propped in the corner behind his desk. It wasn’t a firearm but it would have to do.

The office had suffered a few break-ins in the old days, Smith had been told, but not in many years. Partly thanks to the city’s colored cops, now in their eighth year on the job, and partly because the Daily Times contained nothing worth stealing, unless the thieves were bibliophiles or had always craved their very own typewriters.

Smith crept to the base of the steps. Steps he knew to be very creaky indeed. Once he started walking up, he’d be a perfect target, trapped in the long stairwell with nowhere to hide. He tried to recall which steps were the loudest.

The floor above him remained quiet. Either the person up there had fled (the fire escape?) or was keeping still, waiting in ambush.

He took a step, then a second. The bat already slippery in his hands.

His third step was a bad choice, creaking loudly. So, element of surprise gone, he charged up the rest of the way. He found himself in the second-floor hallway, a light glowing above him. The hallway felt wider than the one downstairs only because it wasn’t lined with as many stacks of newspapers.

A door behind him led to a bathroom. It was nearly closed but not latched, so he kicked it open and the door swung clear and banged into the wall, no one there.

He heard a low moan. Coming from Bishop’s office. Then the sound of traffic, a car driving past, louder than it should have been: a window must be open, despite the night’s January chill.

He crept forward until he was nearly in front of Bishop’s open door. Pressed his back against the wall. This would make a lot more sense if he was holding a gun. He waited a beat, then quickly leaned over to get a look inside.

No one fired at him, no one leapt out of a corner. No one was there at all.

Except there, on the floor. The sound of something crashing before, he realized now, had been Arthur Bishop falling.

The publisher lay not completely flat but close, the room too cramped with its massive desk and chairs and side tables and stacks of books for Bishop’s tall frame to fit. He lay mostly on his stomach, but one of his shoulders was wedged against the side of the desk, and his legs were bent. One of his hands pressed against the floor, fingers taut, knuckles up, the Oriental rug bunching from the pressure. His other hand, the left, was inside his jacket, like he’d been looking for something there, and the wide-eyed look on his face confirmed he’d found it.

Blood soaked the rug beneath him in an expanding circle.

The window behind his desk was open. Smith wanted to go to Bishop first, but he couldn’t risk the fact that a gunman might be hiding on the fire escape, so he ran to the window, looked out and down. No one. Behind the building was a narrow alley, then another building. If the gunman wasn’t hiding in another room, he’d made his way down the fire escape just as Smith had crept up the stairs, and he was long gone.

Bishop wasn’t, not yet.

Smith dropped the bat and helped Bishop roll onto his back. Bishop’s eyes were still open wide, the pupils moving the tiniest bit.

“Hang in there, Mr. Bishop, you hang in there.”

Smith knew the odds a man could survive a shot to the center of the chest, and he knew how long an ambulance would take to get to this neighborhood. He grabbed the phone off Bishop’s desk nonetheless and called the hospital. Then he hung up and dialed a number he knew so well.

Seconds later, just as he noticed that the low moan from his boss had stopped, his previous boss answered the phone.

For seven years and nine months, Sergeant Joe McInnis had been serving as the lone white cop in the Negro precinct. He had walked into plenty of rooms with murder victims, but this was the first time he’d received the call from a man who used to be one of his officers.

The office of Arthur Bishop smelled like cordite, McInnis noted before he’d even stepped inside. The cramped room felt cold from the open back window, yet the scent of gunfire hadn’t faded.

Smith had claimed Bishop was still alive when he’d called, but he wasn’t anymore.

The body was warm, no pulse, eyes open. He lay on his back, arms bent in that cluttered space, as awkward as every other murdered body McInnis had the misfortune of viewing. Folks who died in their sleep often looked as peaceful as that phrase implied, but people who were killed never looked restful, their bodies tense and crooked as if still containing the energy to do all the things they never would.

Behind McInnis stood two of his officers, Boggs and Jones. The latter was a wide-eyed rookie, now viewing a murder victim for the first time in his life. “Don’t touch anything,” McInnis reminded him.

Boggs, however, was a seven-year veteran, having witnessed all manner of crime scenes. The real reason McInnis had chosen this pair to come along, though, was that Boggs and Smith had once been partners. They had started together in April of ’48, part of the inaugural class of Negro officers McInnis had been tapped to lead. The light-skinned, square-jawed Boggs was strict and deeply serious. He had struck McInnis as too intellectual for the job in ’48; he still seemed more at home when combing through police records or encouraging kids on the sidewalk to stay in school than when confronting a violent felon, yet the years had toughened him. In contrast, Smith had always been a handful, chafing against rules and regulations as if they’d been designed specifically to annoy him. He’d resigned only two and a half years after they’d started.

McInnis figured Boggs would be able to read Smith better than McInnis ever could.

McInnis was not unaware of the fact that he was the only white man present, though he’d grown used to this. He had not signed up to be the lone sergeant to the Negro officers, but once he’d been made to understand that he couldn’t turn down the assignment, he’d resigned himself to doing the best job he could. At first, communication had been a challenge. Sometimes a comment or situation would seem to register with his officers on different frequencies than it did him, codes with unexpected meanings, complex understandings he couldn’t quite fathom. Sometimes the translating and rephrasing and explaining grew onerous, exasperating, for him and for them. He worked hard to overcome this, and the misunderstandings had become less common over the years, something he took a not insignificant amount of pride in.

But stress made things worse, and cops were almost always stressed.

As McInnis knelt beside the body, trying to get as good a look as he could without disturbing the scene, Boggs and Jones stood at the entrance, Smith behind them. McInnis smelled booze, and, among haphazard piles of paper that seemed to cascade into each other, he saw a single glass on Bishop’s messy desk. A tiny amount of what looked like whiskey at the bottom.

McInnis carefully stepped around the desk, where a drawer was half open. He did not see a gun or a shell casing, at least not yet. No blood on the windowpane, nothing unusual on the fire escape.

“Jones, go down and check the perimeter of the building and the fire escape, look for a weapon or blood or anything else that shouldn’t be there.”

“Yes, sir.”

Blood spatter along one of the bookshelves to McInnis’s left. So Bishop hadn’t been at his desk when he’d been shot. If Bishop had been moving from behind his desk and toward the shooter, the blood could have come from his back. McInnis slowly moved in a circle, seeing a smaller amount of blood on another bookshelf, possibly from Bishop’s hand as he’d fallen. Or possibly from the assailant’s.

McInnis walked out to Smith and Boggs in the hallway. He folded his arms and stared at his former officer. Who smelled like liquor. McInnis thought of the glass on the dead man’s desk. He studied Smith’s clothes, searching for signs of blood or a struggle, but apart from the lack of a tie and his top two buttons being undone, which in Smith’s case was likely a stylistic insouciance, nothing looked off. Smith was handsome, dark-skinned, with a rakish charm the other officers had seemed to envy.

His eyes usually weren’t this wide.

“Homicide will be here soon,” McInnis explained. Homicide meant white detectives; the Negro officers were only beat cops, as none had been promoted to sergeant or detective. Most white cops in Atlanta despised the Negro officers; they’d tried to sabotage and undercut them from the very beginning, and even now, seven-plus years into this racial experiment, most still seemed to hope that the Negro cops would all be fired or would just mysteriously disappear one day.

Homicide detectives would be overjoyed to find a drunk Negro in the vicinity of a dead body. That meant this was McInnis’s case for maybe a few minutes.

“Tell me, what happened?”

“Right before I called you, I heard a shot, or shots.”

“Which? Shot or shots?”

“I don’t know. I was . . . asleep. I’d been working on a story downstairs—my office is the one below that room,” and he pointed down the hall. “I heard a shot, or shots, I don’t know, and it woke me up. Then I heard a shout, a man’s voice. Could have been Bishop, could have been someone else.”

“What did he say?”

“I couldn’t tell. I heard a slam, it must have been his body hitting the ground. Then footsteps, the shooter probably, and I called out to Bishop, asked if he was okay. I grabbed that bat,” and he motioned to a baseball bat on the floor of the hall, which McInnis had already spotted, “and came up the steps. He was lying on his stomach, just barely holding himself up with his right hand, and he was moaning. I rolled him over, I touched the windowpane when I looked outside, I made the call on that phone, but otherwise I didn’t touch anything.”

Smith had seemed shaken at first, but his recitation of facts seemed to be calming him. Like this was a few years ago and he was recapping just another crime scene to his sergeant, the discipline and old habits forcing this chaotic event into a clarity that allowed him to take the next step, and then the next.

“Did you see anyone?”

“No. I heard movement, like I said, but by the time I got here, the shooter was gone. The window was open, so I’m figuring the fire escape. Then I called you. No more than two minutes after hearing the shot.”

McInnis took a hard look at Smith. “You’ve been drinking.”

“Yessir, it’s late and I was blocked on a story. It’s what we writers do. I got a flask on my desk downstairs. But I’m not drunk.”

McInnis wondered how differently this might have gone if Boggs alone had responded to the call. How differently would Boggs and Smith have behaved without a superior officer present? Without a white man present? What other secrets might have poured forth?

“Did you shoot him?”

Smith’s eyebrows shot up. Perhaps he was so thrown by the body that he hadn’t thought that many steps ahead. Perhaps he was drunker than he claimed and couldn’t think clearly. Perhaps he’d been friendly enough with the dead man that he was still coming to grips with his loss and hadn’t yet realized, with the kind of cagey strategizing Smith had always seemed to excel at, that he was in serious trouble.

“No, sir. Sergeant, it happened exactly like I said.”

McInnis kept his own mouth shut, just watching Smith. Giving him some more silence, to do with as he pleased.

“I did not kill him. I liked the man.” A pause. “Well, maybe didn’t like him so much, but I admired him.”

Already Smith was contradicting himself.

McInnis stepped closer and put a hand on Smith’s shoulder. He seldom touched his officers. “You know you’re going to be interrogated tonight. You know they’re going to want to clear this case fast, and that means driving it right over you. So if you didn’t do this, then you need to give us something, right now.”

The whites of Smith’s eyes were tinged red, either from drink or from the horrific way he’d been awoken.

“Sergeant, I have no idea what happened. None.”

McInnis took back his hand. They felt awkwardly close together.

“Can I take another look inside?” Smith asked.

“From out here, yes.”

McInnis stepped back and let Smith walk up to the threshold. Smith took in the scene again, then said, “His desk is never messy like that. All those papers everywhere.”

“He might have leaned on them, messed them up when he stood,” McInnis noted.

“Or whoever shot him might have been looking for something. Didn’t have time to clean up after he realized I was coming.”

Smith stared a moment longer, shaking his head.

Boggs couldn’t resist saying, “Bad night to be drinking.”

Smith scowled at his ex-partner. “It’s just alcohol, preacher’s son. It don’t make me no killer.”

“Smith,” McInnis said, “once Homicide shows up, any way they slice it, you’re going to be spending the night in the station, understand? You need to stay calm and not push their buttons.” Smith had always been an expert button-pusher, like with the “preacher’s son” comment.

“Yes, sir.”

“I can call you a lawyer,” Boggs said. “My father knows a few.”

Smith nodded, sweat running down his cheeks now. The hallway was not warm.

“I need to pat you down,” McInnis said. “Sorry, but that’s how it works and you know it.”

McInnis didn’t linger on the look in Smith’s eyes, just stood there and waited the two seconds it took for Smith to hold out his arms. Smokes in his shirt pocket, a wallet with eighteen bucks in his right pants pocket, keys in his left. Nothing else. McInnis hoped for Smith’s sake that whatever gun had killed Bishop was a different caliber than any Smith owned.

“What else can you tell us?” McInnis asked after he’d finished. “Was he sleeping around or worried about money, did you overhear any heated arguments recently?”

Smith uncharacteristically silent for a spell.

McInnis pressed, “Who would’ve wanted to hurt him?”

“He’s the owner of the paper, so plenty of folks would want to hurt him. I mean, you don’t read this paper, do you?”

“From time to time.” But not, in truth, that often.

“I read it,” Boggs said. “Your stories first, every time.”

That didn’t surprise McInnis; Boggs no doubt read four or five newspapers every day.

“We cover politics, crime, society, everything. Make a lot of folks angry. You should see some of the hate letters we get, especially lately. There’s this lawsuit against us, and now the Attorney General’s trying to—”

“What lawsuit?”

They heard sirens. Getting louder.

“Jesus Christ,” Smith said, the reality seeming to hit him all the harder now that a squad car was here. Car doors slammed shut. More sirens in the distance. “I can’t believe this.”

The same kinds of white cops Smith hadn’t been able to stand working with were almost here, and this time they were coming for him.

THE WHITE PRISON guard appeared uncomfortable with the idea of allowing these three men to converse alone.

A motley collection they made. On one side of the table: the young Negro prisoner, thin arms jutting through his too-big striped prison shirt, hair in need of a trim. On the other side: the short white attorney, gray hair slicked back with a lotion the guard could surely smell even from so many feet away. And beside him, the wild card: the “attorney’s assistant,” tall and nearly as old as the attorney, white hair at his temples, but skin the same color as the prisoner’s, though a shade lighter. Who had heard of a Negro working with a white attorney like this?

Arthur Bishop, the salt-and-pepper-haired man in question, began to worry that the guard suspected he was there under false pretenses.

In which case, the guard was right.

Atlanta did in fact have some Negro attorneys, but they were fewer in number than Negro doctors or Negro dentists, Negro business owners or Negro insurance men. In fact, Bishop would have bet Atlanta had more Negroes running million-dollar businesses (Atlanta Life Insurance Company, Atlanta First Credit Union, the Colored Hair Care Emporium, etc.) than Negro lawyers. It wasn’t that colored folk couldn’t learn the law; the problem was that no one wanted a Negro lawyer representing them. If you were on trial for theft or murder or assault in the South, the only thing a Negro lawyer would do for you is incur the wrath of white judges who couldn’t stand the sight of a dark-skinned man speaking in measured tones about statutes and jurisprudence and whatnot. Better to have colored folk check your heart and your teeth and your bank accounts, but let a white man defend you if, God forbid, you ever found yourself at the mercy of a white jury.

Which is why Randy Higgs, twenty-three and soon to be on trial for rape, was being represented by Welborn T. Kirk, whose skin could not have been more pale had he spent the last ten years in a North Georgia cave. Despite his courtly name, he hailed from a small firm that represented more than its share of indigent clients.

“We’ll be all right, Joe,” Kirk told the suspicious guard. “If he manages to break those chains I’ll holler real loud, awright?”

Joe shook his head. “Your funeral. You got fifteen minutes.”

“Nah, Joe, I believe I get an hour for visits like these,” and Kirk, still standing, shuffled through the papers he’d already laid across the desk. “Filled out the L-5 paperwork right here.” He offered a manila folder to the guard. Bishop could just barely spot the tip of a five-dollar bill sticking out.

Joe’s beefy face appeared bored, perhaps even mildly insulted, as he took the folder, opened it, and pretended to read through the complex legal jargon of the L-5. Then he handed it back to Kirk, minus Abe Lincoln.

“Sixty minutes, then.”

The white guard walked away and positioned himself in the far corner, leaving the three of them sitting at that long table bisecting the narrow room. Along one side were the visitors, the attorneys and relatives, and on the other side sat the doomed in their striped clothes and funk of twice-weekly showers.

“One hour is not long as these kinds of interviews go,” Bishop said. He had already checked the space for microphones, spotting none. And the lack of a two-way mirror left him slightly reassured. Still, they needed to keep their voices low so as not to be overheard.

Bishop had, in his many days as a journalist, sat in even less hospitable places than this. He’d conducted interviews in backyard shacks, at roadside work camps, at crime scenes, and in combat zones, across several states and abroad. Still, prisons made him enormously uncomfortable, in ways this white lawyer could not appreciate. “We’d best begin.”

Bishop wore a brown tweed jacket over a tan shirt and red tie—not his best attire by a long shot, but he hadn’t wanted to overshadow the white attorney whose assistant he was pretending to be. He did not like the fact that he was here under false pretenses, as it felt like an ethical violation to this old-school journalist, but he had accepted long ago that the skewed rules of Southern justice sometimes meant he had to bend his own.

“Mr. Bishop is the man I told you about,” Kirk told his young client. “He’s the publisher of the Atlanta Daily Times.”

Higgs was imprisoned here to await trial because a young white woman, eighteen, had accused him of rape.

“Nice to meet you, sir,” Higgs said. Decent enough manners, Bishop thought. He didn’t know the kid’s family, which had made him even more reluctant to come. If he tried to aid every poor Negro who may have been unjustly accused, he would manage to do little else. The ability to wisely choose one’s battles was one of the keys to Bishop’s success.

As publisher and editor-in-chief, Bishop was both an awardwinning writer and an astute businessman. He owned not only the Daily Times but also seven smaller papers in five Southern states. Thanks to a network of train-riding vendors, who sold the paper to passengers and at stations, and thanks to the train porters themselves, who deliberately and neatly left well-read copies at small Southern stops and cities across the North and Midwest, the Daily Times and its affiliates boasted a readership well into the hundreds of thousands.

The white lawyer said, “Why don’t you tell Mr. Bishop exactly what you told me.”

Higgs looked dead at Bishop and said, “I didn’t do it.”

Bishop almost wanted to smile at the naïveté. “A bit more detail would help,” he said. “Mr. Kirk already told me, for example, that you and she were lovers.”

Higgs nodded, looking down. Still embarrassed to talk about sex, and on trial for rape! He’d best get used to that right quick.

“But I never did that. Never . . . raped Martha. We were, the two of us were, we were a couple. I mean . . . she was the one who, you know.”

“I’m afraid I don’t know,” Bishop said, folding his hands on the table. “The only way this can work, young man, is if you speak honestly and completely. That means no ‘you know how it is’ and no ‘that sorta thing.’” Be explicit, Bishop’s favorite writing instructor had drilled into his head many years ago. Nowhere was that harder to do, but more important, than when covering the finer points of love and sex in the Jim Crow South.

“All right,” Higgs said, still talking to his lap. “She was the one who . . . who got things going. Who started it.”

Kirk surreptitiously passed Bishop a pencil. The guard had refused to let Bishop bring a pen into the room, but apparently the guard had not frisked the white lawyer as thoroughly. Bishop opened his notebook and placed it in his lap, blindly scribbling notes at crotch level so as not to be seen.

“She initiated a romantic relationship?” he asked, spelling it out.

Eyes up, finally. “Yes, sir.”

“Forward, was she? Bit of a Jezebel?”

“No, sir,” and Higgs appeared insulted, “I mean, she’s the one who started it, but she’s a good girl. I don’t want to be saying bad about her.”

Bishop glanced at Kirk, two older men wanting to shake their heads at the folly of youth. The young woman he didn’t want to say anything bad about had put him here. She was but one person, yet she had set in motion a vast machinery fully capable of crushing Higgs, a veritable army of Confederate wrath that, once set to march, was unlikely to be stopped. And the kid blanched when Bishop dared call her a name!

“She’s falsely accused you of raping her and you don’t want to be saying bad things about her?”

“I just don’t . . . It ain’t her that’s doing this, sir. It’s her family.”

“She’s certainly playing along with their wishes, isn’t she?”

No response. Again Higgs stared at his hands, manacled together and attached via a chain to the desk in front of them.

“You still think she’s your Juliet, despite where you’re sitting right now? This is your little twist on Shakespearean tragedy? Except, only one of you will die.”

Higgs looked up, lost among the references. “I just want to set the record straight, sir, that’s all. Mr. Kirk said your paper might could help with that.”

“I make no promises, young man. A lot of variables go into whether or not I publish a piece. And I’ll be honest, there’s a lot about this that makes me disinclined to print a single word. But I’ll hear you out if you tell me your story, starting from the beginning.”

Kirk added, “And don’t forget to mention the love letters.”

Bishop asked, “What love letters?”

“The ones she sent him.”

Bishop looked at Higgs, who nodded. Then back at the lawyer. “When were they sent?”

“We have two, the second of which was sent three days before she filed the charge. Meaning two days after the night she claims the first rape occurred.”

“The letters are dated?”

“And we have the postmarked envelopes, in matching stationery.” Kirk grinned. He knew what got a journalist’s attention; solid documentation was always top of the list.

“Where are they?”

“The letters are in a safe place.”

“I’ll need to see them.”

“We can arrange that.”

Bishop thought for a moment. He reached into his pocket, popped open his watch. “All right, young man, we’re down to fifty-two minutes. Let’s hear your love story.”

SMITH WAS DONE with Bertha. They’d had their laughs, it had been fun, but that fun had been so long ago. Now he just hated her. She was recalcitrant, she would never do what he asked, and every time he tried to push the buttons that had once caused such joyous music, all he received was frustration.

He pushed her buttons again, but they jammed.

“Goddamn it!” He X’d out the word and started again. Checked his watch—shit, ten minutes until deadline. Bryan Laurence, the fastidious news editor, would be knocking on his door any minute now to complain, remind him of certain realities, time-honored practices, the need for careful editing, the respect for their hardworking typographers, stereotypers, and engravers, who had much to do and couldn’t be expected to rush their jobs just because Smith needed extra time with his.

So he kept typing on Bertha, the black Victrola 600 he’d been using since he’d started at the Daily Times. The K stuck, the E only worked half the time (the E! Hardly an uncommon letter), and the Y was so wobbly he expected the strike pad to fly off every time he used it. He found himself trying to use words without Y, omitting adverbs from his lexicon, using “claims” or “states” instead of “says,” though he knew Laurence wo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...