I don't know why people say time heals all wounds. Time only aggravates mine.

My maternal grandparents were Japanese citizens who lived in Kyoto and immigrated to San Francisco during the early 1900s. My paternal grandparents were ethnic Koreans who moved to Los Angeles shortly after the Empire's victory in 1948. There were more opportunities in the United States of Japan then, especially since the Empire was rebuilding so many of the cities that were in ruins. My parents met during the 1974 Matsuri, a festival at a Shinto shrine in Irvine. My father served as a mecha technician and worked on the maintenance of their armor plating. My mother was an officer who worked as a navigator aboard the mecha Kamoshika. She recognized my dad at the shrine for the work he did on their BP generator. They each picked out an o-mikuji from the o-mikuji box, wondering what fortunes those little strips of paper foretold. By pure coincidence, both of their messages read that a momentous event would occur that day and alter their destinies forever. After sharing jokes and chiding each other about destiny and politics in the corps, they agreed to go to their favorite ramen shop for dinner.

I was born two years later.

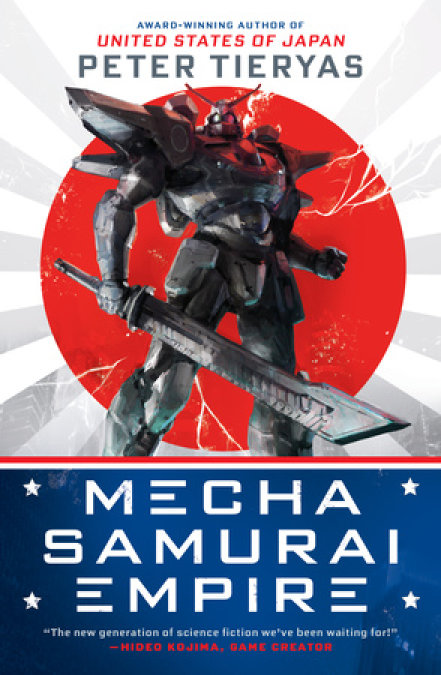

My earliest memory with them is at a mecha factory in Long Beach. The armored legs were bigger than most buildings I'd seen. By the time I was three, I was waging wars against the Nazis with mecha toys my dad had built for me. He'd made me a special jimbaori, and I loved the way the old samurai surcoats gave my mechanical warriors a regal bearing. Neither of my parents got to pilot an actual mecha even though both wished they could. Maybe they'd have gotten the chance if they'd had more time.

The greatest threat during their lives wasn't the Germans but American terrorists who called themselves George Washingtons. The George Washingtons were rumored to be so ruthless, they'd cut off the ears of our soldiers to wear as necklaces. In 1978, hundreds of the terrorists launched themselves at the city hall in San Diego and killed thousands of our citizens. Three months later, they carried out another attack, killing many innocent civilians in the Gaslamp Quarter, including the wife of an important general.

Mom and Dad were ordered to the front in early 1980. They came back home to visit every few months, but neither of them spoke much during their years of service. My father spent most of his time brooding, and the only time I saw even a hint of affection from my mother was when she'd be humming military songs to herself. The last memory I have of them is the morning they left. They told me they'd see me in three months. I still remember the bright colors of the jacketlike haoris they wore over their kimonos and how attracted I was to the golden embroidery. We ate our breakfast in silence. My eggs were too salty, my anchovies were hard, and the pickled tsukemono smelled funny. They usually left without saying much. But that morning, my mom stopped as she was about to leave, came back inside, and gave me a kiss on the forehead.

Nineteen eighty-four was a bloody year. Lots of kids in the Empire became orphans that year. I was no exception. My parents were killed in two separate battles four days apart.

The corporal who came to tell me wept as he spoke. Mom had saved his life in battle, so he had taken the news very hard. "Your mother loved nashis," he told me, having brought a box full of the sweet Asian pears. "She used to cut them up into small pieces to share with her whole unit, and she'd always save one piece just to show she was thinking of you."

Concepts like life and death were hard for me to grasp at that age. Even as he told me stories about my parents, I kept on wondering when he'd go away and my parents would return. It took me a full year to realize they were never coming back, and by then, I was living with a stingy "guardian" who'd been ordered by the government to adopt me, as I had no surviving family members. His primary business had been construction with the hotels in Tijuana and San Diego, but the revolt had put an end to all that. My adoptive father insisted that my adoptive mother measure the amount of rice she was scooping for me. If I left even a little bit of food on my plate, I'd get a severe scolding for "wasting food," which both my adoptive brothers did without a second thought.

Knowing my parents had served aboard mechas, I glorified them. I swore I would grow up to be a mecha pilot protecting the Empire against its enemies. My adoptive parents called it a pipe dream and sent me away as soon as I was eligible for boarding school, in Granada Hills within the California Province, where I've been for nearly a decade.

Now, with my high-school graduation coming in a few months, I practice almost every day on the mecha simulations. Like most kids who grew up in the eighties, I play portical games. The mecha simulations take place inside arcade booths that re-create visuals captured from real-life footage, with surround sound that makes the experience immersive. I wear haptic controls and drive the mecha with a simplified interface that simulates piloting. While I engage in many battles, the one I go back to most often is the fight in San Diego in which my mother was killed.

The Kamoshika was an older Kaneda-class mecha, larger but less deadly than the Torturer-class mechas that were slowly replacing them. Samurai Titan was their nickname because they were so massive. The Kamoshika was essentially a mountain-sized warrior with robotic joints and a face mask protecting its bridge in the head.

It'd been called in to investigate suspicious activity by the George Washingtons. A rebel leader calling herself Abigail Adams led a surprise attack that decimated one of our battalions. The lieutenant colonel in charge of the security station had sent an SOS before communications were cut.

Playing the sim again, I watch as our forces disconnect all electricity to that region of the city. Our soldiers switch to infrared mode, but it's like shadow dancing as they tiptoe their way across a blackened San Diego. The terrorists fire flare guns into the sky, causing bright orbs to reveal the presence of the mecha. There is a frenzied commotion as the GWs prepare for what is designed as the ultimate trap.

They've gathered twenty-two Neptune Tactical Missile Launchers they obtained from the Nazis (even though the Germans would later claim they were stolen) along with five Panzer Maus IX Supertanks. When the Kamoshika arrives at the scene, there is a simultaneous barrage. The pilot realizes it's an ambush and has a split second when he can choose to flee. But it's in an area full of civilians, and the Kamoshika has a sizable military escort that would be helpless against the Panzers and their biomorphs if it made a tactical retreat. It decides to stand its ground and fight, absorbing all the punishment it can. Its endeavor to protect those behind it is not very successful. I watch in slow motion as the armored suit gets incinerated and the BP generator gets exposed, resulting in total meltdown.

This is one of those battles that can't be won in the simulation. If I choose to escape, a great portion of our armed forces gets eliminated and the civilian death toll is catastrophic. If I take the brunt of the blast and fight as hard as I can against the remaining terrorists, I die and leave a young me bereaved.

All these years since the battle, I still struggle with the nightmare scenario that haunted my childhood.

For some kids, academic achievement comes naturally. Unfortunately, I'm not one of them. I work all night, but my grades are only a little above average. I know that won't cut it.

On the main island, the most prestigious military school is the Imperial Japanese Army Academy (Rikugun Shikan Gakko), and the principal way to get accepted is completion of a rigorous three-year course at one of the preparatory schools called Rikugun Yonen Gakko. That, or you show exemplary service as an enlisted soldier and are younger than twenty-five years of age.

If the entrance admission were based on my grades alone, my chances of getting into the top school in the USJ, Berkeley Military Academy (BEMA), would be nonexistent. It's not as if I have a rich family who can buy my way in, either. The only path open to me is to get a good score on the military supplement to the weeklong imperial exams, then hope I can obtain a military recommendation from someone important who notices my test results. It's something I pray to the Emperor for every day because I know I have only a one percent chance of success. Fortunately, the academy isn't looking just for good potential soldiers. They want the best gaming minds to interface with the portical controls on their most advanced machinery. There is historical precedent. The most prominent was one of the best mecha pilots, a cadet with the code name Kujira. She too had average grades and did poorly on the general imperial exams. But her military simulation scores are the best in recorded academy history, and she is a legend as one of our most decorated pilots.

That's partly why I've spent almost every night for the past two years playing the mecha simulations at the Gogo Arcade and why I'm here a week before we're taking the test.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved