- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

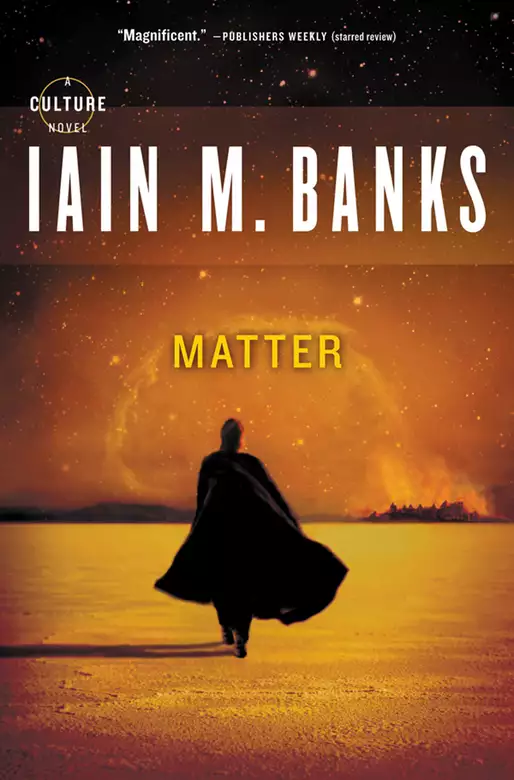

Synopsis

In a world renowned even within a galaxy full of wonders, a crime within a war. For one brother it means a desperate flight, and a search for the one - maybe two - people who could clear his name. For his brother it means a life lived under constant threat of treachery and murder. And for their sister, even without knowing the full truth, it means returning to a place she'd thought abandoned forever.

Only the sister is not what she once was; Djan Seriy Anaplian has changed almost beyond recognition to become an agent of the Culture's Special Circumstances section, charged with high-level interference in civilisations throughout the greater galaxy.

Concealing her new identity - and her particular set of abilities - might be a dangerous strategy, however. In the world to which Anaplian returns, nothing is quite as it seems; and determining the appropriate level of interference in someone else's war is never a simple matter.

MATTER is a novel of dazzling wit and serious purpose. An extraordinary feat of storytelling and breathtaking invention on a grand scale, it is a tour de force from a writer who has turned science fiction on its head.

Release date: February 10, 2009

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Matter

Iain M. Banks

A light breeze produced a dry rattling sound from some nearby bushes. It lifted delicate little veils of dust from a few sandy patches nearby and shifted a lock of dark hair across the forehead of the woman sitting on the wood and canvas camp chair which was perched, not quite level, on a patch of bare rock near the edge of a low ridge looking out over the scrub and sand of the desert. In the distance, trembling through the heat haze, was the straight line of the road. Some scrawny trees, few taller than one man standing on another’s shoulders, marked the course of the dusty highway. Further away, tens of kilometres beyond the road, a line of dark, jagged mountains shimmered in the baking air.

By most human standards the woman was tall, slim and well muscled. Her hair was short and straight and dark and her skin was the colour of pale agate. There was nobody of her specific kind within several thousand light years of where she sat, though if there had been they might have said that she was somewhere between being a young woman and one at the very start of middle age. They would, however, have thought she looked somewhat short and bulky. She was dressed in a pair of wide, loose-fitting pants and a thin, cool-looking jacket, both the same shade as the sand. She wore a wide black hat to shade her from the late morning sun, which showed as a harsh white point high in the cloudless, pale green sky. She raised a pair of very old and worn-looking binoculars to her night-dark eyes and looked out towards the point where the desert road met the horizon to the west. There was a folding table to her right holding a glass and a bottle of chilled water. A small backpack lay underneath. She reached out with her free hand and lifted the glass from the table, sipping at the water while still looking through the ancient field glasses.

“They’re about an hour away,” said the machine floating to her left. The machine looked like a scruffy metal suitcase. It moved a little in the air, rotating and tipping as though looking up at the seated woman. “And anyway,” it continued, “you won’t see much at all with those museum pieces.”

She put the glass down on the table again and lowered the binoculars. “They were my father’s,” she said.

“Really.” The drone made a sound that might have been a sigh.

A screen flicked into existence a couple of metres in front of the woman, filling half her field of view. It showed, from a point a hundred metres above and in front of its leading edge, an army of men – some mounted, most on foot – marching along another section of the desert highway, all raising dust which piled into the air and drifted slowly away to the south-east. Sunlight glittered off the edges of raised spears and pikes. Banners, flags and pennants swayed above. The army filled the road for a couple of kilometres behind the mounted men at its head. Bringing up the rear were baggage carts, covered and open wagons, wheeled catapults and trebuchets and a variety of lumbering wooden siege engines, all pulled by dark, powerful-looking animals whose sweating shoulders towered over the men walking at their sides.

The woman tutted. “Put that away.”

“Yes, ma’am,” the machine said. The screen vanished.

The woman looked through the binoculars again, using both hands this time. “I can see their dust,” she announced. “And another couple of scouts, I think.”

“Astounding,” the drone said.

She placed the field glasses on the table, pulled the brim of her hat down over her eyes and settled back in the camp seat, folding her arms and stretching her booted feet out, crossed at the ankle. “Having a snooze,” she told the drone from beneath the hat. “Wake me when it’s time.”

“Just you make yourself comfortable there,” the drone told her.

“Mm-hmm.”

Turminder Xuss (drone, offensive) watched the woman Djan Seriy Anaplian for a few minutes, monitoring her slowing breathing and her gradually relaxing muscle-state until it knew she was genuinely asleep.

“Sweet dreams, princess,” it said quietly. Reviewing its words immediately, the drone was completely unable to determine whether a disinterested observer would have detected any trace of sarcasm or not.

It checked round its half-dozen previously deployed scout and secondary knife missiles, using their sensors to watch the still distant approaching army draw slowly closer and to monitor the various small patrols and individual scouts the army had sent out ahead of it.

For a while, it watched the army move. From a certain perspective it looked like a single great organism inching darkly across the tawny sweep of desert; something segmented, hesitant – bits of it would come to a stop for no obvious reason for long moments, before starting off again, so that it seemed to shuffle rather than flow en masse – but determined, unarguably fixed in its onward purpose. And all on their way to war, the drone thought sourly, to take and burn and loot and rape and raze. What sullen application these humans devoted to destruction.

About half an hour later, when the front of the army was hazily visible on the desert highway a couple of kilometres to the west, a single mounted scout came riding along the top of the ridge, straight towards where the drone kept vigil and the woman slept. The man showed no sign of having seen through the camouflage field surrounding their little encampment, but unless he changed course he was going to ride right into them.

The drone made a tutting noise very similar to the one the woman had made earlier and told its nearest knife missile to spook the mount. The pencil-thin shape came darting in, effectively invisible, and jabbed the beast in one flank so that it screamed and jerked, nearly unseating its rider as it veered away down the shallow slope of ridge towards the road.

The scout shouted and swore at his animal, reining it in and turning its broad snout back towards the ridge, some distance beyond the woman and the drone. They galloped away, leaving a thin trail of dust hanging in the near-still air.

Djan Seriy Anaplian stirred, sat up a little and looked out from under her hat. “What was all that?” she asked drowsily.

“Nothing. Go back to sleep.”

“Hmm.” She relaxed again and a minute later was quietly snoring.

The drone woke her when the head of the army was almost level with them. It bobbed its front at the body of men and animals a kilometre distant while Anaplian was still yawning and stretching. “The boys are all here,” it told her.

“Indeed they are.” She lifted the binoculars and focused on the very front of the army, where a group of men rode mounted on especially tall, colourfully caparisoned animals. These men wore high plumed helmets and their polished armour glittered brightly in the glare. “They’re all very parade ground,” Anaplian said. “It’s like they’re expecting to bump into somebody out here they need to impress.”

“God?” the drone suggested.

The woman was silent for a moment. “Hmm,” she said eventually. She put the field glasses down and looked at the drone. “Shall we?”

“Merely say the word.”

Anaplian looked back at the army, took a deep breath and said, “Very well. Let us do this.”

The drone made a little dipping motion like a nod. A small hatch opened in its side. A cylinder perhaps four centimetres wide and twenty-five long, shaped like a sort of conical knife, rolled lazily into the air then darted away, keeping close to the ground and accelerating quickly towards the rear of the column of men, animals and machines. It left a trail of dust for a moment before it adjusted its altitude. Anaplian lost sight of its camouflaged shape almost immediately.

The drone’s aura field, invisible until now, glowed rosily for a moment or two. “This,” it said, “should be fun.”

The woman looked at it dubiously. “There aren’t going to be any mistakes this time, are there?”

“Certainly not,” the machine said crisply. “Want to watch?” it asked her. “I mean properly, not through those antique opera glasses.”

Anaplian looked at the machine through narrowed eyes for a little, then said, slowly, “All right.”

The screen blinked into existence just to one side of them this time, so that Anaplian could still see the army in the distance with the naked eye. The screen view was from some distance behind the great column now, and much lower than before. Dust drifted across the view. “That’s from the trailing scout missile,” Turminder Xuss said. Another screen flickered next to the first. “This is from the knife missile itself.” The camera in the knife missile registered the tiny machine scudding past the army in a blur of men, uniforms and weapons, then showed the tall shapes of the wagons, war machines and siege engines before banking sharply after the tail end of the army was passed. The rushing missile stooped, taking up a position a kilometre behind the rear of the army and a metre or so above the road surface. Its speed had dropped from near-supersonic to something close to that of a swiftly flying bird. It was closing rapidly with the rear of the column.

“I’ll synch the scout to the knife, follow it in behind,” the drone said. In moments, the flat circular base of the knife missile appeared as a dot in the centre of the scout missile’s view, then expanded until it looked like the smaller machine was only a metre behind the larger one. “There go the warps!” Xuss said, sounding excited. “See?”

Two arrowhead shapes, one on either side, detached from the knife missile’s body, swung out and disappeared. The monofilament wires which still attached each of the little warps to the knife missile were invisible. The view changed as the scout missile pulled back and up, showing almost the whole of the army ahead.

“I’ll get the knife to buzz the wires,” the drone said.

“What does that mean?”

“Vibrates them, so that whatever the monofils go through, it’ll be like getting sliced by an implausibly sharp battleaxe rather than the world’s keenest razor,” the drone said helpfully.

The screen displaying what the scout missile could see showed a tree a hundred metres behind the last, trundling wagon. The tree jerked and the top three-quarters slid at a steep angle down the sloped stump that was the bottom quarter before toppling to the dust. “That took a flick,” the drone said, glowing briefly rosy again and sounding amused. The wagons and siege engines filled the view coming from the knife missile. “The first bit’s actually the trickiest . . .”

The fabric roofs of the covered wagons rose into the air like released birds; tensed hoops of wood – cut – sprang apart. The giant, solid wheels of the catapults, trebuchets and siege engines shed their top sections on the next revolution and the great wooden structures thudded to a halt, the top halves of some of them, also cut through, jumping forward with the shock. Armthick lengths of rope, wound rock-tight a moment earlier, burst like released springs then flopped like string. The scout missile swung between the felled and wrecked machines as the men in and around the wagons and siege engines started to react. The knife missile powered onwards, towards the foot soldiers immediately ahead. It plunged into the mass of spears, pikes, pennant poles, banners and flags, scything through them in a welter of sliced wood, falling blades and flapping fabric.

Anaplian caught glimpses of a couple of men slashed or skewered by falling pikeheads.

“Bound to be a few casualties,” the drone muttered.

“Bound to be,” the woman said.

The knife missile was catching glimpses of confused faces as men heard the shouts of those behind them and turned to look. The missile was a half-second away from the rear of the mass of mounted men and roughly level with their necks when the drone sent,

– Are you sure we can’t . . . ?

– Positive, Anaplian replied, inserting a sigh into what was an entirely non-verbal exchange. – Just stick to the plan.

The tiny machine nudged up a half-metre or so and tore above the mounted men, catching their plumed helmets and chopping the gaudy decorations off like a harvest of motley stalks. It leapt over the head of the column, leaving consternation and fluttering plumage in its wake. Then it zoomed, heading skywards. The following scout missile registered the monofil warps clicking back into place in the knife missile’s body before it swivelled, rose and slowed, to look back at the whole army again.

It was, Anaplian thought, a scene of entirely satisfactory chaos, outrage and confusion. She smiled. This was an event of such rarity that Turminder Xuss recorded the moment.

The screens hanging in the air disappeared. The knife missile reappeared and swung into the offered hatchway in the side of the drone.

Anaplian looked out over the plain to the road and the halted army. “Many casualties?” she asked, smile disappearing.

“Sixteen or so,” the drone told her. “About half will likely prove fatal, in time.”

She nodded, still watching the distant column of men and machines. “Oh well.”

“Indeed,” Turminder Xuss agreed. The scout missile floated up to the drone and also entered via a side panel. “Still,” the drone said, sounding weary, “we should have done more.”

“Should we.”

“Yes. You ought to have let me do a proper decapitation.”

“No,” Anaplian said.

“Just the nobles,” the drone said. “The guys right at the front. The ones who came up with their spiffing war plans in the first place.”

“No,” the woman said again, rising from her seat and, turning, folding it. She held it in one hand. With the other she lifted the old pair of binoculars from the table. “Module coming?”

“Overhead,” the drone told her. It moved round her and picked up the camp table, placing the glass and water bottle inside the backpack beneath. “Just the two nasty dukes? And the King?”

Anaplian held on to her hat as she looked straight up, squinting briefly in the sunlight until her eyes adjusted. “No.”

“This is not, I trust, some kind of transferred familial sentimentality,” the drone said with half-pretended distaste.

“No,” the woman said, watching the shape of the module ripple in the air a few metres away.

Turminder Xuss moved towards the module as its rear door hinged open. “And are you going to stop saying ‘no’ to me all the time?”

Anaplian looked at it, expressionless.

“Never mind,” the drone said, sighing. It bob-nodded towards the open module door. “After you.”

1. Factory

The place had to be some sort of old factory or workshop or something. There were big toothed metal wheels half buried in the wooden floors or hanging by giant spindles from the network of iron beams overhead. Canvas belts were strung all over the dark spaces connecting smaller, smooth wheels and a host of long, complicated machines he thought might be something to do with weaving or knitting. It was all very dusty and grimy-looking. And yet this had been that modern thing; a factory! How quickly things decayed and became useless.

Normally he would never have considered going anywhere near some place so filthy. It might not even be safe, he thought, even with all the machinery stilled; one gable wall was partially collapsed, bricks tumbled, planks splintered, rafters hanging disjointed from above. He didn’t know if this was old damage from deterioration and lack of repair, or something that had happened today, during the battle. In the end, though, he hadn’t cared what the place was or had been; it was somewhere to escape to, a place to hide.

Well, to regroup, to recover and collect himself. That put a better gloss on it. Not running away, he told himself; just staging a strategical retreat, or whatever you called it.

Outside, the Rollstar Pentrl having passed over the horizon a few minutes earlier, it was slowly getting dark. Through the breach in the wall he could see sporadic flashes and hear the thunder of artillery, the crump and bellowing report of shells landing uncomfortably close by and the sharp, busy rattle of small arms fire. He wondered how the battle was going. They were supposed to be winning, but it was all so confusing. For all he knew they were on the brink of complete victory or utter defeat.

He didn’t understand warfare, and having now experienced its practice first hand, had no idea how people kept their wits about them in a battle. A big explosion nearby made the whole building tremble; he whimpered as he crouched down, pressing himself still further into the dark corner he had found on the first floor, drawing his thick cloak over his head. He heard himself make that pathetic, weak little sound and hated himself for it. Breathing under the cloak, he caught a faint odour of dried blood and faeces, and hated that too.

He was Ferbin otz Aelsh-Hausk’r, a prince of the House of Hausk, son of King Hausk the Conqueror. And while he was his father’s son, he had not been raised to be like him. His father gloried in war and battle and dispute, had spent his entire life aggressively expanding the influence of his throne and his people, always in the name of the WorldGod and with half an eye on history. The King had raised his eldest son to be like him, but that son had been killed by the very people they were fighting, perhaps for the last time, today. His second son, Ferbin, had been schooled in the arts not of war but of diplomacy; his natural place was supposed to be in the court, not the parade ground, fencing stage or firing range, still less the battlefield.

His father had known this and, even if he had never been as proud of Ferbin as he had of Elime, his murdered first son, he had accepted that Ferbin’s skill – you might even term it his calling, Ferbin had thought more than once – lay in the arts of politicking, not soldiering. It was, anyway, what his father had wanted. The King had been looking forward to a time when the martial heroics he had had to undertake to bring this new age about would be seen for the rude necessities they had been; he had wanted at least one of his sons to fit easily into a coming era of peace, prosperity and contentment, where the turning of a pretty phrase would have more telling effect than the twisting of a sword.

It was not his fault, Ferbin told himself, that he was not cut out for war. It was certainly not his fault that, realising he might be about to die at any moment, he had felt so terrified earlier. And even less to his discredit that he had lost control of his bowels when that Yilim chap – he had been a major or a general or something – had been obliterated by the cannon shot. Dear God, the man had been talking to him when he was just . . . gone! Cut in half!

Their small group had ridden up to a low rise for a better look at the battle. This was a modestly insane thing to do in the first place, Ferbin had thought at the time, exposing them to enemy spotters and hence to still greater risk than that from a random artillery shell. For one thing, he’d chosen a particularly outstanding mersicor charger as his mount that morning from the abroad-tents of the royal stables; a pure white beast with a high and proud aspect which he thought he would look well on. Only to discover that General-Major Yilim’s choice of mount obviously pitched in the same direction, for he rode a similar charger. Now he thought about it – and, oh! the number of times he’d had cause to use that phrase or one of its cousins at the start of some explanation in the aftermath of yet another embarrassment – Ferbin wondered at the wisdom of riding on to an exposed ridge with two such conspicuous beasts.

He had wanted to say this, but then decided he didn’t know enough about the procedures to be followed in such matters actually to speak his mind, and anyway he hadn’t wanted to sound like a coward. Perhaps Major-General or General-Major Yilim had felt insulted that he’d been left out of the front-line forces and asked instead to look after Ferbin, keeping him close enough to the action so that he’d later be able to claim that he’d been there at the battle, but not so close that he risked actually getting involved with any fighting.

From the rise, when they achieved it, they could see the whole sweep of the battleground, from the great Tower ahead in the distance, over the downland spreading out from the kilometres-wide cylinder and up towards their position on the first fold of the low hills that carried the road to Pourl itself. The Sarl capital city lay behind them, barely visible in the misty haze, a short-day’s ride away.

This was the ancient county of Xilisk and these were the old playgrounds of Ferbin and his siblings, long depopulated lands turned into royal parks and hunting grounds, filled with overgrown villages and thick forests. Now, all about, their crumpled, riven geography sparkled with the fire of uncounted thousands of guns, the land itself seemed to move and flow where troop concentrations and fleets of war craft manoeuvred, and great sloped stems of steam and smoke lifted into the air above it all, casting massive wedged shadows across the ground.

Here and there, beneath the spread of risen mists and lowering cloud, dots and small winged shapes moved above the great battle as caude and lyge – the great venerable warbeasts of the sky – spotted for artillery and carried intelligence and signals from place to place. None seemed mobbed by clouds of lesser avians, so most likely they were all friendly. Poor fare compared to the days of old, though, when flocks, squadrons, whole clouds of the great beasts had contended in the battles of the ancients. Well, if the old stories and ancient paintings were to be believed. Ferbin suspected they were exaggerated, and his younger half-brother, Oramen, who claimed to study such matters, had said well of course they were exaggerated, though, being Oramen, only after shaking his head at Ferbin’s ignorance.

Choubris Holse, his servant, had been to his left on the ridge, digging into a saddle bag and muttering about requiring some fresh supplies from the nearest village behind them. Major – or General – Yilim had been on his right, holding forth about the coming campaign on the next level down, taking the fight to their enemies in their own domain. Ferbin had ignored his servant and turned to Yilim out of politeness. Then, mid-word, with a sort of tearing rush of sound, the elderly officer – portly, a little flushed of face and inclined to wheeze when laughing – was gone, just gone. His legs and lower torso still sat in the saddle, but the rest of him was all ripped about and scattered; half of him seemed to have thrown itself over Ferbin, covering him in blood and greasily unknowable bits of body parts. Ferbin had stared at the remains still sitting in the saddle as he wiped some of the gore off his face, gagging with the stink and the warm, steaming feel of it. His lunch had left his belly and mouth like something was pursuing it. He’d coughed, then wiped his face with a gore-slicked hand.

“Fucking hell,” he’d heard Choubris Holse say, voice breaking.

Yilim’s mount – the tall, pale mersicor charger which Yilim had spoken to more kindly than to any of his men – as though suddenly realising what had just happened, screamed, reared and fled, dumping what was left of the man’s body on to the torn-up ground. Another shell or ball or whatever these ghastly things were landed nearby, felling another two of their group in a shrieking tangle of men and animals. His servant had gone too, now, Ferbin realised; mount toppled, falling on top of him. Choubris Holse yelled with fright and pain, pinned beneath the animal.

“Sir!” one of the junior officers shouted at him, suddenly in front of him, pulling his own mount round. “Ride! Away from here!”

He was still wiping blood from his face.

He’d filled his britches, he realised. He whipped his mount and followed the younger man, until the young officer and his mount disappeared in a sudden thick spray of dark earth. The air seemed to be full of screeches and fire; deafening, blinding. Ferbin heard himself whimper. He pressed himself against his mount, wrapping his arms round its neck and closing his eyes, letting the pounding animal find its own way over and around whatever obstacles were in its path, not daring to raise his head and look where they were going. The jarring, rattling, terrifying ride had seemed to last for ever. He heard himself whimpering again.

The panting, heaving mersicor slowed eventually.

Ferbin opened his eyes to see they were on a dark wooded track by the side of a small river; booms and flashes came from every side but sounded a little further away than they had. Something burned further up the stream, as though overhanging trees were on fire. A tall building, half ruined, loomed in the late afternoon light as the labouring, panting mount slowed still further. He pulled it to a stop outside the place, and dismounted. He’d let go of the reins. The animal startled at another loud explosion, then went wailing off down the track at a canter. He might have given chase if his pants hadn’t been full of his own excrement.

Instead he waddled into the building through a door wedged open by sagging hinges, looking for water and somewhere to clean himself. His servant would have known just what to do. Choubris Holse would have cleaned him up quick as you like, with much muttering and many grumblings, but efficiently, and without a sly sneer. And now, Ferbin realised, he was unarmed. The mersicor had made off with his rifle and ceremonial sword. Plus, the pistol he’d been given by his father, and which he had sworn would never leave his side while the war was waged, was no longer in its holster.

He found some water and ancient rags and cleaned himself as best he could. He still had his wine flask, though it was empty. He filled the flask from a long trough of deep, flowing water cut into the floor and rinsed his mouth, then drank. He tried to catch his reflection in the dark length of water but failed. He dipped his hands in the trough and pushed his fingers through his long fair hair, then washed his face. Appearances had to be maintained, after all. Of King Hausk’s three sons he had always been the one who most resembled their father; tall, fair and handsome, with a proud, manly bearing (so people said, apparently – he did not really trouble himself with such matters).

The battle raged on beyond the dark, abandoned building as the light of Pentrl faded from the sky. He found that he could not stop shaking. He still smelled of blood and shit. It was unthinkable that anyone should find him like this. And the noise! He’d been told the battle would be quick and they would win easily, but it was still going on. Maybe they were losing. If they were, it might be better that he hid. If his father had been killed in the fighting he would, he supposed, be the new king. That was too great a responsibility; he couldn’t risk showing himself until he knew they had won. He found a place on the floor above to lie down and tried to sleep, but could not; all he could see was General Yilim, bursting right in front of him, gobbets of flesh flying towards him. He retched once more, then drank from the flask.

Just lying there, then sitting, his cloak pulled tight around him, made him feel a little better. It would all be all right, he told himself. He’d take a little while away from things, just a moment or two, to collect his wits and calm down. Then he’d see how things were. They would have won, and his father would still be alive. He wasn’t ready to be king. He enjoyed being a prince. Being a prince was fun; being a king looked like hard work. Besides, his father had always entirely given everybody who’d ever met him the strong impression that he would most assuredly live for ever.

Ferbin must have nodded off. There was noise down below; clamour, voices. In his jangled, still half-drowsy state, he thought he recognised some of them. He was instantly terrified that he would be discovered, captured by the enemy or shamed in front of his father’s own troops. How low he had fallen in so short a time! To be as mortally afraid of his own side as of the enemy! Steel-shod feet clattered on the steps. He was going to be discovered!

“Nobody in the floors above,” a voice said.

“Good. There. Lay him there. Doctor . . .” (There was some speech that Ferbin didn’t catch. He was still working out that he’d escaped detection while he’d been asleep.) “Well, you must do whatever you can. Bleye! Tohonlo! Ride for help, as I’ve asked.”

“Sir.”

“At once.”

“Priest; attend.”

“The Exaltine, sir—”

“Will be with us in due course, I’m sure. For now the duty’s yours.”

“Of course, sir.”

“The rest of you, out. Give us some air to breathe here.”

He did know that voice. He was sure he did. The man giving the orders sounded like – in fact must be – tyl Loesp.

Mertis tyl Loesp was his father’s closest friend and most trusted adviser. What was going on? There was much movement. Lanterns cast shadows from below on to the dark ceiling above him. He shifted towards a chink of light coming from the floor nearby where a broad canvas belt, descending from a giant wheel above, disappeared through the planking to some machinery on the ground floor. Shifting, he could peer through the slit in the floor to see what was happening beneath.

Dear God of the World, it was his father!

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...