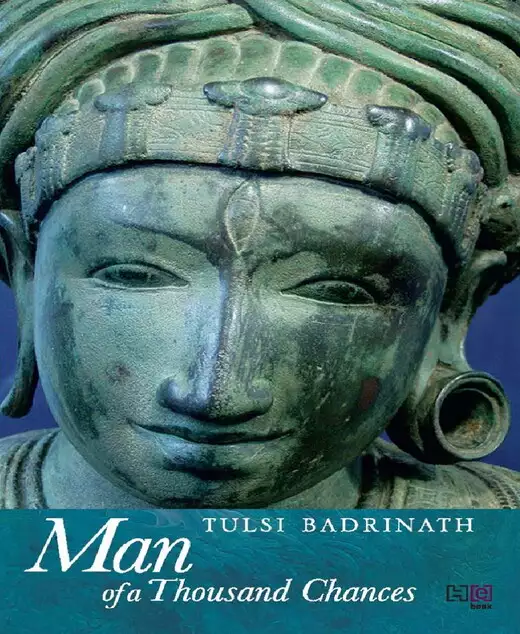

Man of a Thousand Chances

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Harihar Arora: second-generation north Indian in Madras, museum curator, indifferent husband, indulgent father ? and thief. Desperate to meet his beloved daughter?s wedding expenses, the otherwise honest Harihar steals a rare gold coin minted by Mughal Emperor Jahangir and pawns it, with every intention of returning it after the wedding. But when he finds himself in a position to redeem it, he learns that it has been melted by the pawnbroker. What follows next forces Harihar to readdress his place in the world, and in his own marriage. Beneath the deceptively simple surface of a story about an ordinary man in a rather extraordinary fix, are questions about the workings of karma, causality and the power of art, that offer profound matter for debate.

Release date: March 12, 2012

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Man of a Thousand Chances

Tulsi Badrinath

runaway’s forehead was unusually bare of decoration, as was the rest of his huge, astonishing body. As he moved towards Harihar,

his bulk shifted in an awkward, complex manner – rising only to collapse – within his loose, creased, grey-black hide. And

yet there was tremendous grace in that gentle swaying stride, his footfall light and soundless despite the heavy iron chain

clamped to his right foreleg. The slant of mellowing sunlight and airborne dust created a golden aura around the animal.

Standing inside the low compound wall of the museum surrounded by his chattering energized colleagues, Harihar saw crowds

gather excitedly on the rooftops of apartments in the distance, and housewives and children peering down from windows several

storeys high trying to get a better look at the road below. Closer to him, men squatted in clusters on narrow sunshades or

teetered on parapet walls. His stomach lurched as a group of high-spirited urchins clambered up a nearby tree; one playful

blow of the elephant’s trunk could knock all of them down. More of his colleagues, the few remaining staff in the museum, came rushing from their posts to watch the spectacle.

‘Escaped from the temple while taking bath!’ exclaimed someone.

‘Just walked out, wouldn’t listen to the mahout, it seems,’ said another.

‘His name is Ayyappan!’ cried a third.

It was early evening, time to go home. The sun hurt Harihar’s eyes, forcing them almost shut. His eyelashes heavy with brightness,

he tilted his head, banishing the sun behind dense foliage. An idea slid into his mind, seductive, dangerous, telling him

the time had come. He tried to ignore it.

Ayyappan’s trunk dangled low over the ground. He drew it aloft in an S, then sent the pink, saliva-wet rim probing the space

ahead. Cars swerved. People scattered like dice, leaping over the metal road-divider, swarming up trees, running for safely,

caring little for ripped clothes or bags lost. Their cries melded in the air with the sound of bells ringing as cyclists peddled

furiously to stay ahead of the mammoth creature. The traffic signal changed colour but no one paid any attention.

Turning to catch a glimpse of the elephant, a man tripped and fell. He rolled to one side in sheer fright, scrambling to get

up before he was trampled upon. On the edge of the road, pressed against high walls, men and women gasped at the sight.

Where was the animal headed?

Harihar stared in awe at the blunt stump-like tusks, the humped unshapely back sloping towards an absurdly small tail, the

yellowish toenails that looked like giant teeth as the elephant lumbered past him. A bullet-hole gaped at the ragged corner

of one flapping, speckled ear. When was the last time he had seen an elephant? He knit his eyebrows, trying to remember – at the Children’s Park… Vandalur Zoo? No, it was at a fair somewhere; he had taken his children Ratan and Meeta

when they were much younger.

Behind the elephant ran a distressed man, barefoot, chequered lungi folded up to his knees, trying to catch up. Probably the

mahout, thought Harihar. Since the elephant had repudiated his trainer and that unique relationship of trust, the situation

was serious.

Two police jeeps and an officer on a motorbike inched cautiously behind the pair while maintaining a safe distance. People

massed between the vehicles, accompanying them on foot. Three large elephants, mahouts perched atop, followed a white van

with the words ‘Madras Zoo’ painted on it. The army of men in pursuit looked grim; the situation could explode in a second,

with a rampant Ayyappan wreaking disaster and death in every direction.

The elephant’s eyes were small, rheumy; his gaze resolute but unfathomable. Free and in possession of his dignity, responding

to an obscure inner urge, Chief Elephant Mylapore Ayyappan trod the hot, tarred road, dictating the pace and direction of

this strange chase. His unhurried walk was deceptive, hiding the great speed with which he could charge. The team of rescuers

moved warily behind him, awaiting their opportunity.

Minutes later, the errant elephant veered left and barged into the vast wooded premises of the museum. There was a collective

intake of breath, and cries of ‘Ayyo’ as the group around Harihar contracted into a small, tight knot. Someone stepped on

his foot. Pushed tight against the wall by uncouth bodies, alien sweat wiped on his skin, Harihar felt breathless. His muscles tensed for flight as he saw the elephant loom into view.

Looking straight on at the two circular mounds defining Ayyappan’s intelligent brow, at the wrinkled face that tapered into

the trunk, it was difficult to gauge his immense size. The elephant sauntered aimlessly for a while, his upraised trunk casually

rifling through the lower branches of trees. The sun glowed within a penumbra of trembling leaves. Suddenly, Ayyappan turned

towards the park, fanning himself with his scarf-like ears, away from where they were standing. The frantic mahout caught

up with him, sweat pouring off his dark, skeletal face.

As his fright ebbed, Harihar saw that a perfect chance had arisen. He had to act upon the idea he had been struggling with

for more than a fortnight. He left the crowd, made his way back to the office even as the zoo van entered the gates. All attention

would be on the elephant; there would be many breaches of routine today. It was the sign he had been waiting for, precipitating

action. Almost as though Ganesha himself had arranged it, sending an elephant this way.

The museum galleries had closed for the day. The high vaulted ceiling of the building arched over him, resting its weight

on thick whitewashed columns. More than a hundred summers had passed since it was built, a venerable defence against the relentless

heat outside.

At 4.58 p.m., quite before he had planned to, Harihar approached the wall of military-green Godrej almirahs in his office,

squeezing machine oil over a bunch of keys in his hand. Stopping at the third cupboard, he quickly inserted a key. The scratched

metal door swung open without a sound, and he carefully released the keys from his grip, willing them to remain silent. The previous day he had tamed its squeaking hinges and left the oiler in his desk, even though he had not committed

himself fully to acting further on his plan.

A bead of sweat rolled down his forehead into his right eye, where it stung. He blinked several times as he reached for a

plastic case marked MC/17AD/J9. Third shelf, second case to the right – he knew the one he wanted. He was about to pick it

up when he realized his hands were oily. He hesitated, loath to ruin his trousers. In a hurried, impatient gesture, he wiped

them clean on his dry hair. Lifting the case with both hands, he was amazed once again by its weight. As he struggled to draw

a circular tissue-wrapped object out of its home, part of its wrapping tore and gold gleamed in the dim, unlit room.

Holding it reverentially in both hands, like an offering, Harihar walked towards a barred window set high in the wall. Catching

the diffused rays of a tired sun, the artefact shone, it glimmered, a pool of molten fire sparkling in his hands.

A single gold coin. It was breathtaking.

Guiding it into his specially reinforced trouser pocket, Harihar recalled the first day he saw it. The plaster cast on public

display had cracked and a new one was to be made. The coin was drawn out of the walk-in steel safe. As he measured it – ten

centimetres and six millimetres – his superior, Mahadevan, the curator, had pointed out its special features. ‘Mughal Emperor

Jahangir ruled sixteen nought five to sixteen twenty-seven. His name means Conqueror of the World.’

Harihar bobbed his chin up and down to show he was paying attention. Dates of historical periods were beyond him.

‘This is one of the world’s biggest historical coins,’ marvelled Mahadevan, handling it with great care. ‘Look at it. Purr-fect

condition! No dents, no scratches. I don’t think it was ever circulated… Jahangir had made some that were presented as a gift from the State. Can you imagine the wealth of his empire?

This one single coin weighs 2 kilos.’

Harihar could feel that very weight now, straining the material of his pants, pulling at the waistband beneath his belt. His

blue shirt clung unpleasantly to his damp back. He walked towards his desk, Mahadevan’s voice continuing to ring in his head.

‘Do you know how much this is worth, Hari? A coin half this weight sold recently for two million dollars at a special auction

for coin-collectors. That’s about… what… eight-nine crores! So imagine how much this would be sold for!

‘There are two coins in the world of this size, Harihar, two, only two whose location we know. One is in the British Museum

and the other one is here,’ finished Mahadevan, gesturing with a flourish towards the coin. ‘In our very own Madras Museum.’

For a long time they had gazed at both sides of the coin, the fabulous strokes of raised calligraphy, the intricate work.

‘Persian, Nastaliq script which his father Akbar loved, couplet in praise of Jahangir’s favourite Queen, Noorjahan, Light

of the World,’ said Mahadevan cryptically.

‘He was besotted by her. His love was so great, he had coins struck in her name. She was the only empress who had her own

coinage, without having ascended the throne! He granted her more and more control over the kingdom as he got addicted to opium

and alcohol. She too was utterly devoted to him.’

But this was no time to reminisce. Reaching his desk, Harihar took from the drawer a similar-looking, but much lighter, package

that he had readied earlier. Swiftly replacing it in the case, Harihar locked the almirah. His breath was uneven, rapid. Something

surged inside his skull, pulsing, rising higher.

Relax, he told himself. It was Friday. The museum would remain closed on Saturday and re-open on Sunday. Anbu and Senthil,

the night-guards, had already passed through this section of the museum – given that the wooden windows were closed and the

ceiling fans switched off. A thorough check of the premises, to make sure no one remained inside, usually took them an hour;

it was unlikely that they would return. If they were to come up, he would tell them that he had fallen asleep in the records

room.

He could hear the commotion outside, below, filtered by walled distance. A sound like a shot erupted nearby. Harihar started,

fingers turning icy. The cavernous central hall was filled with the multiplying echo of wings beating in distress. Beyond

the balustrade, he could see the frantic blur of flapping wings, a small brown body swooping through air, searching for an

exit. At any other time it would have been funny – his jittery response to the sound of a sparrow trapped inside the building.

Not now.

As he left his office, the grey stone floor seemed to expand endlessly ahead of him. Harihar half walked, half shuffled towards

a corridor lined with open metal shelves and untidy, dusty files. It led to the staff toilets at the back where the air was

smoky blue, dense with stale odours. The stench became more pronounced. Turning into the one marked Ladies, Harihar closed

the door behind him. Leaning weakly against it, he took a long, deep breath, realizing the smell had receded.

He would have to think fast. The lining of his pocket would give way any time, it seemed. Bloody incompetent tailor, could

not do even a small job like this properly, he cursed, slowly pulling the coin out. All he had to do was make the pockets

deeper, wider, using very thick fabric in two of his trousers – needed it for the heavy keys he carried around, Harihar had said – how difficult was that? Harihar had worn the trousers alternately

this entire week, while he dithered.

Harihar tucked the coin halfway into his waistband, tightening his belt around it. It lay uncomfortably tilted over his stomach.

He had just broken all the rules of care learnt from Mahadevan. The sweat on his belly would react with the metal. The dust

outside, heat, the humidity, would all combine to stain its innocence.

Glancing at his face in the hazy mirror over the washbasin, he dropped his eyes at once. He did not recognize the greying,

careworn man in there. Harihar Arora, Assistant to the Curator of the Madras Museum, honest, hard-working, about to take a

step that would change his life forever. He did not want to linger too long near that reflection.

Fishing a red plastic comb out of his back pocket, he hurriedly tidied his oil-smeared hair, questioning himself vaguely.

Things were entirely reversible at this stage. But there was no answer except the course he had decided on. Just borrowing

it, he told himself. Stocktaking – laborious, tedious in nature – had just been successfully completed. They would not have

to undergo another one for three months. He would replace the coin by then.

Looking around him, he made for the plain wooden door on the other side of the toilet. Kamala, the secretary, lone woman in

their department, had the dingy, cobweb-festooned place all to herself. Senthil had once told Harihar that he was too embarrassed

to walk into the ladies’ toilet in the evenings, though he was supposed to check it. ‘Only Missess Kamala on this floor, sar.

No problem.’ It was then that Senthil had told him, in passing, about the door that led to a staircase outside. Made in earlier callous times, it was a separate entrance meant only for those who used to clean the toilets. Now, it remained

unused, bolted.

Harihar tried to open it but the wood had expanded and one end of the warped door was stuck in the frame. After moments of

silent struggle, it yielded and he felt his eyes narrow, adjust to an oblong of light, the subdued glare from outside. Dropping

to his knees, he moved out onto the rusting platform. A gust of warm air enveloped him. The sky was a swirl of yellow and

orange and red, darkening blue showing through here and there; the sun was gone. There were no unusual sounds. He could not

hear the war-cries of the chase. The elephant must have been coaxed to amenity, or maybe it had left the museum and gone elsewhere.

He forced the door shut behind him, glad in a way that it had come out of true. It would remain stuck, and the first thing

Sunday morning he would bolt it from the inside. He could see the spreading canopy of gulmohar trees, framed in segments by

the railings, and beyond the red brick of one wall, the melancholy dome of the museum. At his elbow was a fall of painted

drainage pipes. He peered over the wrought-iron staircase that unwound like a spring at the back of the building. It was quite

a distance.

He felt dizzy as he descended, turning with every weighted step, feeling confined between the railing and the helix of steps

above and below him, hoping all the while that no one would see him. The entire weight of his body and the coin seemed to

rest on his bent knees. One turn, then another. A wash of sweat covered his face. The awkward position, the heavy disc pulling

on his spine and the cramped twist of the spiral steps propelled him lower and lower, knees buckling, faster than he wanted to go.

He saw a pile of garbage, cracked plastic bottles, empty wrappers and ice-cream sticks on the ground and knew he was on the

last step. He felt he was being watched and turned to look into a pair of grave, wise eyes. His heart skipped a beat before

he realized that they belonged to a large complacent monkey. It quirked an eyebrow and looked knowingly at him from the comfort

of its perch on a garbage bin nearby. He stepped gingerly, trying to save his shoes from ruin but, distracted by the monkey,

he had not gauged how deep the litter would be. His foot sank. In danger of over-balancing, he clung to the railing, using

it to wade to the temporary safety of open ground. A rotten banana peel adhered to the top of one shoe.

He could see two guards securing the front gates, and one chasing illicit couples off the patchy lawn. Deciding not to cut

across, Harihar looped around the back of the building. Once he was away from the steps, it did not matter if he was seen.

The sky was grey now, the trees a dark intense green. He could hear the angry murmur of traffic on the road outside the compound,

car-horns blown insistently, buses straining to carry the rush-hour crowd. And somewhere in that melee stomped a brave, disgruntled

elephant.

No one was around. Harihar walked with a deliberately measured pace, his nerves afire, taking the short cut between two buildings

that ended in the parking area. Round steamy piles of elephant dung lay stinking at various points, a great mess of fibre

and green substance. He held his breath whenever he walked past one of them.

There were two motorbikes left in the shed. In a second, he had straddled the bike and kicked the pedal. The extra weight

helped. It started with a thunderous roar.

‘Aay, Harihar!’

He jerked around and saw Chandran, an over-friendly personal assistant who worked in the Amaravati sculptures gallery.

‘Vaat da, late-aa?’

‘Aanh. I was watching the elephant and all. Then I went to Ramu’s Tiffin. Feeling hungry… ate nicely,’ said Harihar, ready

with his answer. ‘Too much trouble to take the bike, one way and all. You saw?’

‘I saw, I saw. It smashed the locked gate and went off, just like that. One stroke. Ppaah, fann-tastic! They say yit is still

on the road, but they could not yable to catch it only.’ He paused to catch his breath and continued, ‘I got caught, by the new Director – always asking for this file, that file. Today marning he wanted some three years old file.

Where to search for it? They all start like this, very full of energy. Then, before they can do yennything, they will be transferred.

But who is there to tell him?’

The strain was unbearable. Harihar was in the worst position possible. Body angled over the tank, arms outstretched, one foot

planted on the ground. His back ached. The edge of the disc was pressing tight against his flesh.

Chandran paused and looked at Harihar. ‘What’s the matter. Not well-aa? Daughter’s wedding tension, enh?’

Harihar nodded, trying to lighten his features with a smile.

Chandran patted him supportively on the back. ‘Look at me, I have three daughters. Not one horoscope is matching…’

Harihar was alarmed. A jocular remark about paunches might result in an unwelcome pat on his stomach. He revved his engine.

‘Getting late, boss,’ he excused himself. ‘Still have vegetables to buy. See you!’

They nodded goodbye at each other. Harihar zoomed through the back gate while Muthu the khaki-clad watchman hastily flung

aside a half-smoked beedi and saluted him.

as people streamed out of their workplaces, the usual evening-return chaos burst onto the main road. A line of stalled cars,

buses and grimy lorries was visible down its length. Wherever a gap opened up between the larger vehicles and yellow auto-rickshaws,

the shiny cycles, motorbikes, dusty scooters and mopeds took their chance. Harihar saw a pair of recalcitrant bullocks urged

forward by their owner, sitting in the cart behind them and twisting their tails, until they could go no further. A lone policeman

stood at the centre of this urban mess, waving his arms furiously and blowing desperate blasts on his whistle.

Harihar edged ahead, keeping to the extreme left, very close to the pavement, praying that he would not hit something or somebody.

Finally reaching a point where he too was blocked, he cut the engine and tried to relieve his spine. Someday very soon, every

inch of every single street would be jammed by vehicles and no one would be able to move. A sense of helpless rage coursed

through him. He could no longer predict to the minute, as he used to, how long it would take him to get from one place to

another.

To his right, a line of seated women loomed over him, staring idly from the large airy openings of a PTC bus. He regretted

not having thought enough about carrying the heavy coin around. Maybe he ought to have just placed it in a briefcase. But

how would he have negotiated the steps then?

A blank mist fogged his head. He worried at its nebulous edges, seeking what he had buried there. Chandran’s words had touched

the core of his dilemma. Daughter’s wedding. His beloved Meeta’s wedding fixedl She was to be given twenty-one sets of clothes, silk and otherwise, gold jewellery, diamond earrings – if possible, silver

vessels, a TV, fridge and a set of furniture. Then there were the expenses related to the wedding: mithai, mewa – those sweetmeats

and dry fruits alone would cost a lot; hiring a wedding hall; feeding all the relatives for three days at the very least;

catering for the main dinner the night of the wedding; videographers; gifts for Harihar’s relatives. If that were not enough

of a drain, a generous gift for the bridegroom and less costly ones for the rest of his family – the list was endless, his

money limited.

Both families had agreed on an auspicious day in about a month’s time. Harihar would have preferred to have the wedding take

place about six months later. It would give him more time to accumulate money, but the pandit had said that if they let pass

this particular date there were no suitable dates for at least eight months thereafter.

The boy was a good match for Meeta. Pleasant-looking, soft-spoken, he seemed to be of good sanskar – manifest qualities inherent

in his soul, acquired over many lifetimes. He worked in a software company and had a master’s degree. Meeta might even settle

abroad someday with him. His family had not asked for a dowry; the expectation was, of course, that in compensation the wedding would be lavish. Harihar had to give her a grand wedding, show the rest of his family, especially

his elder brother Ashok-ji, what he was capable of.

The previous year, Ashok’s daughter, Avantika, had run away with a Tamil boy, a Nadar, depriving Ashok of the chance to host

a showy wedding besides of course splattering his honour with mud. Meeta therefore was the first granddaughter of the family

to be getting married in the proper way; it was a matter of prestige.

The problem was that Harihar had never been able to save much. When the date of the wedding was finalized, he was caught short.

Everything considered – savings, loans from his other brothers, his wife Sarla’s jewellery, personal loan from the office,

he was short by two lakhs. He had a deposit with CBF, but Sanjeev, his best friend from his college days, told him he had

to wait until maturity when he would get a bonus, definitely. But that was only ten days after the wedding.

Then about two weeks ago, the idea came to him. A heavy, almost freak rainfall had flooded the lower floor of the museum.

Luckily, nothing was damaged; the paintings were displayed on the second floor. But the water had seeped into the safe, finding

a gap between the massive, Chubb locked door and the iron-reinforced floor. Mahadevan had to turn the combination several

times that morning, after Harihar inserted the second key, in order to open the safe. It was a temperamental lock, moody in

rainy weather and in January. Luckily that day, it yielded to persuasion. All the valuables were rescued and placed in the

almirahs upstairs. It was decided they would remain there until the safe was dry and the lock in a good mood. For once, the

historical objects were not under dual custody.

A woman swerved into Harihar’s view. Anxiously clutching the hand of a little girl, she dodged a daredevil biker. She was

midway across the road when a tremendous racket rose from the vehicles around him, startling him out of his reverie. The policeman

had cleared the traffic-jam, and engines reverberated in anticipation of movement. Somehow, inch by inch, the mass of vehicles

convulsed towards different exit points without much damage to bumpers and paint. Harihar concentrated on slipping past a

tilted, overcrowded PTC bus, a tumour of men erupting from its side. The elephant was nowhere in sight.

He rode steadily for half an hour, until he left behind the main arteries of the city and turned into a crowded wholesale

bazaar, each of its throbbing capillaries flaunting wares unique to itself. Gliding past the small shops, past the shoppers

gathered on the pavement, he saw an evening flame raised to the gods of wealth and prosperity; a boy wearing dirty shorts

scrubbing a huge iron vessel meant for cooking feasts; clusters of spoked bicycle wheels adorning a shop.

Darkness had fallen and the cold glint of the street lights fell on translucent glass bangles, an array of steel plates, brass

vessels – an endlessly varied inventory of delight. His senses were met with the tempting aroma of hot jalebis wallowing in

syrup, and the vision of a group of women in pretty embroidered pastel burqas bargaining animatedly in a garment shop.

Normally, Harihar loved the bustle and spectacle of the place, so different from the enforced calm and lethargy of the museum.

He never got the time to frequent the Flower Bazaar since it was not near his home. Now, it all seemed dream-like, with the

weight of gold on him. He saw familiar sights as though from a distance, for he sat strangely within his skin. He could not believe that he had actually taken the coin. With a great effort of will he rode on.

Soon the pure, heady fragrance of jasmines filled the air. A man sat at a rickety wooden stall, expertly binding a pair of

fresh buds with banana fibr. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...