- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A gentle romance begins innocently enough in the stalls of a London theatre where Catherine is enjoying her ninth and Christopher his thirty-sixth visit to the same play. He is a magnificent young man with flame-coloured hair. She is the sweetest little thing in a hat. There is just one complication: Christopher is 25, while Catherine is just a little bit older. Flattered by the passionate attentions of youth, Catherine, with marriage and motherhood behind her, is at first circumspect, but finally succumbs to her lover's charms.

Release date: March 6, 2014

Publisher: Audible Studios

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

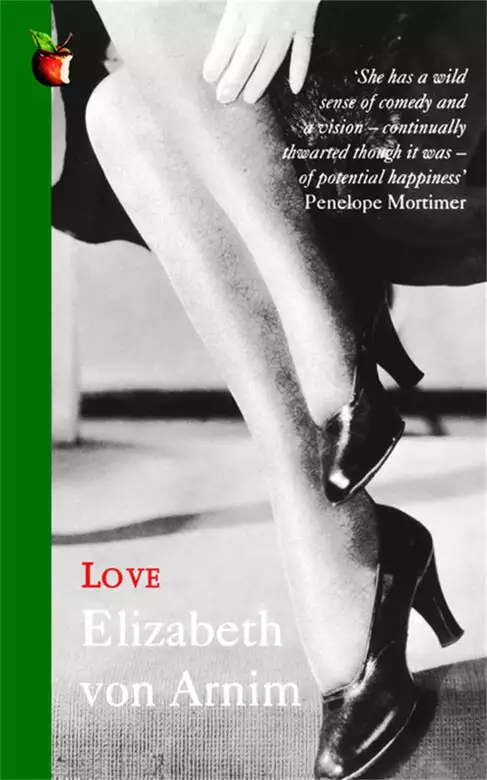

Love

Elizabeth von Arnim

Elizabeth heard about Frere in the first place from his mother, and was intrigued by her account of having had a child by a sporting gentleman called Colonel Reeves. Mary Frere put the baby in an orphanage and forgot about him until rumour reached her that he had fought gallantly in the Royal Flying Corps in the still recent war and was now an undergraduate at Cambridge. Did Elizabeth smell the plot for a novel? She asked Arnold Bennett to fix a meeting over lunch. He obliged, and Elizabeth and Frere became at once ‘tremendous friends’. Elizabeth invited him to come to her Swiss chalet in August and settle her library. He accepted delightedly if, nearer the time, he felt nervous at the thought of the distinguished guests. But he endeared himself to all at once by appointing himself major-domo. Lieber Gott Elizabeth called him. She never allowed guests to interfere with her working hours, but she always took a walk before lunch, and Lieber Gott was frequently her companion. He fell head over heels in love with her.

He had come at a time when she was in need of tenderness. Her marriage to Francis Earl Russell had finally collapsed, and he was busy blackguarding her to anyone who would listen. There had always been some man in her life, and as well as the few who played significant parts, there were usually young men about whose company she enjoyed as well as pale followers who lingered on, enjoying a meagre diet of attention.

After he went back to England, Frere deluged Elizabeth with adoring letters. She was flattered and fascinated, but she had obtained freedom from the domination of men at last, and so far from needing constant companionship, she was happier, and felt far more vital alone. Or so she often said, and it was true up to a point. In London she danced with Frere and enjoyed the company of his young friends, to whom he was proud to introduce her. For her part, she discreetly pushed his career. In high spirits she began Vera, her final stiletto-thrust in the long battle with her husband. Frere could be a sympathetic companion, but his glooms in private made him difficult. He was never as good in reality as on paper; quite early on there were rows. Frere, who had never known mother love, wanted above everything to be emotionally dependent on Elizabeth. She used to tease him, and sometimes enjoyed putting young women in his way. The novelistic possibilities of the situation did not escape her.

Michael Frere, when he met Elizabeth, like Christopher in Love ‘didn’t know much about women. Up to this he had had only highly unsatisfactory, rough and tumble, relations with them.’ He wrote to her like a boy for the first time in love. ‘I find myself pinned down by dreams, dreams of the unattainable.’ Those close to her remarked how young and well Elizabeth was looking. Getting rid of Francis Russell was not enough to account for it. Michael and she became lovers, in fact, in 1921 on his second visit to the chalet. In Love Catherine, though worldly wise, is strictly proper. But in life, by this time, Elizabeth allowed herself some latitude. Even when her marriage to Russell was breaking up she was dining in London regularly with his brother Bertrand. True to form, she was also trying to persuade him to collaborate with her in an epistolary novel. But what else went on? Whatever it was, Bertrand Russell advised her not to be indiscreet when writing to Francis. Given Russell’s reputation, Frere suspected the worst, and may not have been wholly satisfied by her reassurance that the laughing philosopher ‘smelt like a bear garden’. However tiresome his moods, Elizabeth did not want to lose Frere; whenever she told him to go, she inevitably whistled him back.

1922 was a bad year for Elizabeth. She was disappointed by some of the reviews of The Enchanted April although it was to prove the most popular — excepting the first — of all her novels. She suffered from depressions that she couldn’t throw off. Her doctor diagnosed menopausal symptoms. If Frere wanted her to marry him she couldn’t because she was still married to Russell and took precautions against his discovering any evidence that might incite him to sue her for adultery. When, for example, friends let her use their house on the Isle of Wight that Christmas, Elizabeth invited Michael to join her, but found him separate lodgings. An incident during the holiday humiliated her. A casual friendship struck up with a father and daughter in a pub led to remarks, made in all innocence by the newcomers on the assumption that Elizabeth was Frere’s aunt. She put this episode into Love. It may well have been what sparked off this novel. There were probably other incidents of a similar nature. ‘But wouldn’t that bore your mother dreadfully?’ a pretty girl at a party says in Love when Christopher counters an invitation to him with: ‘No. You come to us.’

Love is a knowing novel even though the facts of life are laid on in water colour. It was a happy idea to begin the story at The Immortal Hour, the musical drama which was drawing a small but enraptured audience to the Regent Theatre in the Spring of 1923. Celtic themes were in fashion just then, and Elizabeth went again and again. She made a stage door call on the leading actor, and he came to tea on a few occasions. It was all very much in keeping with the beginning of Love, to which, no doubt, Elizabeth and Frere went often together.

She was at pains in the description of Christopher in the novel to make him as unlike Frere as possible. We are never told much more about his background than that he has expectations from an uncle with whom he plays golf, that he shares rooms with a misogynistic friend, and works in an ‘office’. If his background is bare, his physical appearance is detailed: great height and flame-coloured hair. Frere was dark and only a few inches taller than Elizabeth’s five foot. In contrast, Elizabeth emphasises Catherine’s resemblance to herself. Christopher thought that he had never heard ‘such a funny little coo of a voice’. Elizabeth had lent that voice to other heroines. Jane Wells said she could make even German sound pretty. Swinnerton, the novelist, compared her voice to ‘a choir-boy with a sore throat’. Her smallness is stressed. Santayana, the philosopher, on first meeting Elizabeth, the mother of grown-up children, was astonished to find that she looked like a child. Her acquaintances must have recognised her before they came to the end of Love’s second page. Wells had advised her that when the younger lover started to cool it was the time for the older to make the break. Had that point been reached in this affair when Love was being written? (I Never Should Have Done It was considered as a subtitle.) Two years after it was published Frere confessed that he was living with a young woman who was forcing him into marrying her. This took Elizabeth by surprise, and she was miserable about it. A year later the marriage took place. Elizabeth told Frere that she never wanted to see him again even though he said that he had been frog-marched to the ceremony. But very soon they were corresponding again. Going through drawers when she was leaving Switzerland in 1929 for a villa on the French Riviera, Elizabeth came across Frere’s letters (‘Some of them very sweet. That had been a funny business. And a sweet one.’) But it was still unfinished. In 1931 Francis Russell died, leaving Elizabeth free to marry again. Frere recalled her at this time, her face scarred by lifting, extremely thin, stockings wound round her legs, her face powdered white, wearing enormous hats. ‘Nevertheless she was still beautiful.’ He was full, as usual, of his own troubles, and thought he was going to die. ‘If he dies the light of my life goes out, and I start dying myself’, she wrote in her diary. But their romance plummeted when Frere’s wife turned up at a Heinemann party and made a scene in Elizabeth’s presence. Elizabeth returned to France the next day and changed her will. Frere was no longer her literary executor. (His unsuitable wife ran away with a taxi driver eventually and he was expecting his divorce decree when Elizabeth met him out walking with a blonde to whom he introduced her as the girl he was about to marry. She was a daughter of Edgar Wallace, the crime writer. When Elizabeth got home she wrote in her diary: ‘I am so glad it is she and not I. What perfect grammar.’) Her last diary entry that year was: ‘So ends 1932. In it, in March, I shed L.G. after nearly twelve years of him. It was high time.’ That was seven years after the publication of Love.

Love gave Elizabeth more trouble than most of her novels. For every page she wrote, she tore up six, and she was never satisfied with the inconclusive ending. She spelled out Catherine’s position at the beginning of Part Two. Catherine thinks she has been ostracised by her family — really only by her preposterous son-in-law, the Reverend Stephen Colquhoun, who discovers that Catherine and Christopher took all night to return to London after a visit to his rectory. They were on Christopher’s motor-bike. The bike had itself become a cause of scandal before it became a supposititious occasion of sin. Stephen found it excruciating to see his mother-in-law in the sidecar, dashing round his parish, scattering his flock. But he is even more concerned to anticipate scandal and expiate sin by the speedy marriage of the errant couple. Not that the idea of a wife so much older than her husband causes him anything but disgust. His hurt is almost lethal when he hears from the pure lips of his adored child-wife (from whom he kept as much of the story as possible) that she sees no difference between her own marriage and theirs.

‘Do you not see it is terrible to marry someone young enough to be your son?’ he had asked sternly — he couldn’t have believed he would ever have to be stern with his own love in such a place, at such an hour.

And she had answered: ‘But is it any more terrible than marrying someone young enough to be your daughter?’

Virginia had answered that. His Virginia. In bed. In his very arms.

For so much of the novel, Stephen is the character who dictates the action and his moral collapse is an extraordinary development of the plot. Elizabeth’s authorial difficulties may well have arisen from finding that she had taken aboard a heavier cargo than her delicate vessel was constructed to carry. Catherine says as much: ‘The stuff one filled life with! And at the faintest stirring of Death’s wings, the smallest movement forward of that great figure from the dark furthermost corner of the little room called life, how instantly one’s eyes were smitten open.’

Agonising about wrinkles round the eyes has no place in the death chamber, but until then Catherine’s predicament had agonised the reader. Part Two spells it out. Catherine enjoyed an enchanted time when bus conductors and taxi drivers called her Miss. She loved Christopher, but she was not in love with him — a very different thing. ‘Her vanity was fed to the point of beatitude.’ Her image in the glass was ‘radiant with the cool happiness of not being in love’. But when at last she agrees to marry Christopher that Indian summer is brought to an end. She falls in love with ‘hopeless completeness’. In doing so, she loses her beauty. Christopher ‘burnt up what had still been left of her youth.’ As Mrs Micham, Catherine’s housekeeper said to herself: ‘It’s them honeymoons.’

It might seem that Catherine’s dramatically sudden ageing is allowed to get out of hand to match the graver development of the plot. She is pictured as if she were one of Macbeth’s witches when Christopher opens the nursery door and sees three ‘grizzled’ women standing round a cot. The account of the face treatment that Catherine had undergone at the hands of a quack was taken from a description given to Elizabeth by Katherine Mansfield, her New Zealand cousin, of her own experience in Paris when she was searching for a cure for consumption. This may have been too tragic a source. If Elizabeth needed copy she had, if Frere is to be believed, her own experience to draw on.

These are questions of tone values. Elizabeth was a tragi-comedienne, and happiest when describing the human situation. It was not only with Frere she discovered that ‘Marriage being mainly repetition, and Christopher now being a husband, he presently began to make fewer rapturous speeches. It was quite unconscious, but as the weeks passed it became natural to love with fewer preliminary cooings — to bill, as it were, without remembering first to coo.’

Terence de Vere White, London 1987

Elizabeth Irene (Liebet) wrote a life of her mother, Elizabeth of the German Garden, under the psuedonym Leslie de Charmes, which was published by Heinemann in 1958. A fuller biography, ‘Elizabeth’ by Karen Usborne, was published by The Bodley Head in 1986.

THE first time they met, though they didn’t know it, for they were unconscious of each other, was at The Immortal Hour, then playing to almost empty houses away at King’s Cross; but they both went so often, and the audience at that time was so conspicuous because there was so little of it and so much room to put it in, that quite soon people who went frequently got to know each other by sight, and felt friendly and inclined to nod and smile, and this happened too to Christopher and Catherine.

She first became aware of him on the evening of her fifth visit, when she heard two people talking just behind her before the curtain went up, and one said, sounding proud, ‘This is my eleventh time’; and the other answered carelessly, ‘This is my thirty-secondth ’—upon which the first one exclaimed, ‘Oh, I say!’ with much the sound of a pricked balloon wailing itself flat, and she couldn’t resist turning her face, lit up with interest and amusement, to look. Thus she saw Christopher consciously for the first time, and he saw her.

After that they noticed each other’s presence for three more performances, and then, when it was her ninth and his thirty-sixth—for the enthusiasts of The Immortal Hour kept jealous count of their visits—and they found themselves sitting in the same row with only twelve empty seats between them, he moved up six nearer to her when the curtain went down between the two scenes of the first act, and when it went down at the end of the first act, after that love scene which invariably roused the small band of the faithful to a kind of mystic frenzy of delight, he moved up the other six and sat down boldly beside her.

She smiled at him, a friendly and welcoming smile.

‘It’s so beautiful,’ he said apologetically, as if this explained his coming over to her.

‘Perfectly beautiful,’ she said; and added, ‘This is my ninth time.’

And he said, ‘This is my thirty-sixth.’

And she said, ‘I know.’

And he said, ‘How do you know?’

And she said, ‘Because I heard you tell some one when it was your thirty-secondth, and I’ve been counting since.’

So they made friends, and Christopher thought he had never seen anybody with such a sweet way of smiling, or heard anybody with such a funny little coo of a voice.

She was little altogether; a little thing, in a little hat which she never had to take off because hardly ever was there anybody behind her, and, anyhow, even in a big hat she was not of the size that obstructs views. Always the same hat; never a different one, or different clothes. Although the clothes were pretty, very pretty, he somehow felt, perhaps because they were never different, that she wasn’t very well off; and he also somehow felt she was older than he was—just a little older, nothing at all to matter; and presently he began somehow also to feel that she was married.

The night he got this feeling he was surprised how much he disliked it. What was happening to him? Was he falling in love? And he didn’t even know her name. It was the night of her fourteenth visit and his forty-eighth—for since they had made friends he went oftener than ever in the hope of seeing her, and the very programme young women looked at him as though they had known him all their lives—that this cold feeling first filtered into his warm and comfortable heart, and nipped its comfort; and it wasn’t that he had seen a wedding ring, for she never took off her absurd, small gloves—it was something indescribably not a girl about her.

He tried to pin it down into words, but he couldn’t; it remained indescribable. And whether it had to do with the lines of her figure, which were rounder than most girls’ figures in these flat days, or with the things she said, for the life of him he couldn’t tell. Perhaps it was her composure, her air of settled safety, of being able to make friends with any number of strange young men, pick them up and leave them, exactly when and how she chose.

Still, it might not be true. She was always alone. Sooner or later, if there were husbands they appeared. No husband of a wife so sweet would let her come out at night like this by herself, he thought. Yes, he probably was mistaken. He didn’t know much about women. Up to this he had only had highly unsatisfactory, rough and tumble relations with them, and he couldn’t compare. And though he and she had now sat together several times, they had talked entirely about The Immortal Hour—they were both so very enthusiastic—and its music, and its singers, and Celtic legends generally, and at the end she always smiled the smile that enchanted him, and nodded and slipped away, so that they had never really got any further than the first night.

‘Look here,’ he said, or rather blurted, the next time he saw her there—he now went as a matter of course to sit next to her—‘you might tell me your name. Mine’s Monckton. Christopher Monckton.’

‘But of course,’ she said. ‘Mine is Cumfrit.’

Cumfrit? He thought it a funny little name; but somehow like her.

‘Just’—he held his breath—‘Cumfrit?’

She laughed. ‘Oh, there’s Catherine as well,’ she said.

‘I like that. It’s pretty. They’re sweet and pretty, said together. They’re—well, extraordinarily like you.’

She laughed again. ‘But they’re not both like me,’ she said. ‘I owe the Cumfrit part to George.’

‘To George?’ he faltered.

‘He provided the Cumfrit. All I did was the Catherine bit.’

‘Then—you’re married?”

‘Isn’t everybody?’

‘Good God, no,’ he cried. ‘It’s a disgusting thing to be. It’s hateful. It’s ridiculous. Tying oneself up to somebody for good and all. Everybody! I should think not. I’m not.’

‘Oh, but you’re too young,’ she said, amused.

‘Too young? And what about you?’

She looked at him quickly, a doubt on her face; but the doubt changed to real surprise when she saw how completely he had meant it. She had a three-cornered face, like a pansy, like a kitten, he thought. He wanted to stroke her. He was sure she was exquisitely smooth and soft. And now there was George.

‘Does he—does your husband not like music?’ he asked, saying the first thing that came into his head, not really wanting in the least to know what that damned George liked or didn’t like.

She hesitated. ‘I—don’t know,’ she said. ‘He—usedn’t to.’

‘But he doesn’t come here?’

‘How can he?’ She stopped, and then said softly, ‘The poor darling’s dead.’

His heart gave a bound. A widow. The beastly war had done one good thing, then,—it had removed George.

‘I say, I’m most frightfully sorry,’ he exclaimed with immense earnestness, and trying to look solemn.

‘Oh, it’s a long while ago,’ she said, bowing her head a little at the remembrance.

‘It can’t be so very long ago.’

‘Why can’t it?’

‘Because you haven’t had time.’

She again looked quickly at him, and again saw nothing but sincerity. Then she was silent a moment. She was thinking, ‘This is rather sweet’—and the ghost of a wistful little smile passed across her face. How old was he? Twenty-five or six; not more, she was sure. What a charming thing youth was,—so headlong, so generous and whole-hearted in its admirations and beliefs. He was a great, loosely built young man, with flame-coloured hair, and freckles, and bony red wrists that came a long way out of his sleeves when he sat supporting his head in his hands during the love scene, clutching it tighter and tighter as there was more and more of love. He had deep-set eyes, and a beautifully shaped broad forehead, and a wide, kindly mouth, and he radiated youth, and the discontents and quick angers and quicker appreciations of youth.

She suppressed a small sigh, and laughed as she said, ‘You’ve only seen me at night. Wait till you see me in broad daylight.’

‘Am I ever to be allowed to?’ he asked eagerly.

‘Don’t you ever come to the matinées?’

She knew he didn’t.

‘Oh—matinées. No, of course I can’t come to matinées. I have to grind all the week in my beastly office, and on Saturdays I go and play golf with an uncle who is supposed to be going to leave me all his money.’

‘You should cherish him.’

‘I do. And I haven’t minded till now. But it’s an infernal tie-up directly one wants to do anything else.’

He looked at her ruefully. Then his face lit up. ‘Sundays,’ he said eagerly. ‘Sundays I’m free. He’s religious, and won’t play on Sundays. Couldn’t I——?’

‘There aren’t any matinées on Sunday,’ she said.

‘No but couldn’t I come and see you? Come and call?’

‘Hush,’ she said, lifting her hand as the music of the second act began.

And at the end this time too, before he could say a word, while he was still struggling with his coat, she slipped away as usual after nodding good night.

The next time, however, he was more determined, and began at once. It seemed to him that he had been thinking of her without stopping, and it was absurd not to know anything at all about a person one thinks of as much as that, except her name and that her husband was dead. It was of course a great stride from blank knowing nothing; and that her husband should be dead was such a relief to him that he couldn’t help thinking he must be falling in love. All husbands should be dead, he considered,—nuisances, complicators. What would have happened if George had been alive? Why, he simply would have lost her, had to give up at once,—before, almost, beginning. And he was so lonely, and she was—well, what wasn’t she? She was so like what he had been dreaming of for years,—a little ball of sweetness, and warmth, and comfort, and reassurance and love.

The next time she came, then, the minute she appeared he went over to where she sat and began. He was going to ask her straight out if he might come and see her, fix that up, get her address; but she chanced to be late that night, and hardly had he opened his mouth when the lights were lowered and she put up her hand and said ‘Hush.’

It was no use trying to say what he wanted to say in a whisper, because the faithful, though few, were fierce, and would tolerate nothing but total silence. Also he was much afraid she herself preferred the music to anything he might have to say.

He sat with his arms folded and waited. He had to wait till the very end of the act, because though he tried again when the curtain went down between its two scenes, and only the orchestra was playing, he was shoo’d quiet at once by the outraged faithful.

She, too, said, putting up her hand, ‘Oh, hush.’

He began to feel slightly off The Immortal Hour. But at last the whole act was over and the lights were up again. She turned her flushed face to him, the music still shining in her eyes. She was always flushed and her eyes always shone at the end of the love scene: nor could he ever see that lovely headlong embrace of the lovers without feeling extraordinarily stirred up. God, to be embraced like that…. He was starving for love.

‘Isn’t it marvellous,’ she breathed.

‘Are you ever going to let me come and see you? he asked, without losing another second.

She looked at him a moment, collecting her thoughts, a little surprised. ‘Of course,’ she then said. ‘Do, Though——’ She stopped.

‘Go on,’ he said.

‘I was going to say, Don’t you see me as it is?’

‘But what is this?’

‘Well, it’s two or three times every week,’ she said.

‘Yes, but what is it? Just a casual picking up. You come—you happen to come—and then you disappear. At any time you might happen not to come, and then——’

‘Why then,’ she finished for him as he paused, ‘you’d have all this beautiful stuff to yourself. I don’t think they ever did that last bit more wonderfully, do you?’ And off she went again, cooing on as usual about The Immortal Hour, and he hadn’t a chance to get in another word before the confounded music began again and the faithful with one accord called out ‘Sh—sh.’

Enthusiasm, thought Christopher, should have its bounds. He forgot that, to begin with, his enthusiasm had far outdone hers. He folded his arms once more, a sign with him of determined and grim patience, and when it was over and she bade him her smiling good night and hurried off without any more words, he lost no time bothering about putting on his coat but simply seized it and went after her.

It was difficult to keep her in sight. She could slip through gaps he couldn’t, and he very nearly lost her at the turn of the stairs. He caught her up, however, on the steps outside, just as she was about to plunge out into the rain, and laid his hand on her arm.

She looked round surprised. In the glare of the peculiarly searching light theatres turn on to their departing and arriving patrons he was struck by the fatigue on her face. The music was too much for her—she looked worn out.

‘Look here,’ he said, ‘don’t run away like this. It’s pouring. You wait here and I’ll get you a taxi.’

‘Oh, but I always go by tube,’ she said, clutching at him a moment as some people pushing past threw her against him.

‘You can’t go by tube to-night. Not in this rain. And you look frightfully tired.’

She glanced up at him oddly and laughed a little. ‘Do I?’ she said. ‘Well, I’m not. Not a bit tired. And I can quite well go by tube. It’s quite close.’

‘You can’t do anything of the sort. Stand here out of the rain while I get a taxi.’ And off he ran.

For a moment she was on the verge of running off herself, going to the tube as usual and getting home her own way, for why should she be forced into an expensive taxi? Then she thought: ‘No—it would be low of me, simply low. I must try and behave like a little gentleman——’ and waited.

‘Where shall I tell him to go to?’ asked Christopher, having got his taxi and put her inside it and simply not had the courage to declare it was his duty to see her safely home.

She told him the address—90A Hertford Street—and he wondered a moment why, living in such a street with the very air of Park Lane wafted down it from just round the corner, she should not only not have a car but want to go in tubes.

‘Can I give you a lift?’ she asked, leaning forward at the last moment.

He was in the taxi in a flash. ‘I was so hoping you’d say that,’ he said, pulling the door to with such vigour that a shower of raindrops jerked off the top of the window-frame on to her dress.

These he had to wipe off, which he did with immense care, and a handkerchief that deplorably was not one of his new ones. She sat passive while he did it, going over the evening’s performance, pointing out, describing, reminding, and he, as he dried, told himself definitely that he had had enough of The Immortal Hour. She must stop, she must stop. He must talk to her, must find out more about her. He was burning to know more about her before the infernally fast taxi arrived at her home. And she would do nothing, as they bumped furiously along, but quote and ecstasise.

That was a good word, he thought, as it came into his head; and he was so much pleased with it that he said it out loud. ‘I wish you wouldn’t ecstasise,’ he said. ‘Not now. Not for the next few minutes.’

‘Ecstasise?’ she repeated, wondering.

‘Aren’t your shoes wet? Crossing that soaking pavement? I’m sure they must be wet——’

And he reached down and began to wipe their soles too with his handkerchief.

She watched him a little surprised, but still passive. This was what it was to be young. One squandered a beautiful clean handkerchief on a woman’s dirty shoes without thinking twice. She observed the thick

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...