- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

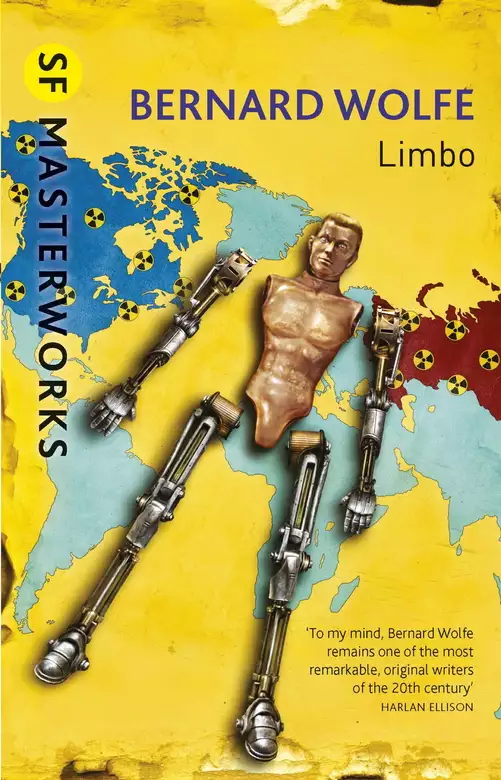

Synopsis

In the aftermath of an atomic war, a new international movement of pacifism has arisen. Multitudes of young men have chosen to curb their aggressive instincts through voluntary amputation - disarmament in its most literal sense. Those who have undergone this procedure are highly esteemed in the new society. But they have a problem - their prosthetics require a rare metal to function, and international tensions are rising over which countries get the right to mine it . . .

Release date: December 15, 2016

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 433

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Limbo

Bernard Wolfe

by Harlan Ellison®

Here’s how it began for you, how you came to realize Bernard Wolfe is one of the finest writers this country has ever produced, how you came to share the years with him.

In 1952, you were still in high school and very impressed with Salinger, Hemingway and Shirley Jackson, taking inordinate pride in having read Moby-Dick in its entirety, even the sections describing the riggings of the Pequod. Then, one day, quite by accident, while looking for a new book of science fiction you’d somehow missed in your voracious reading, you came across something called Limbo by someone named Bernard Wolfe. And you bought it, or borrowed it, or perhaps even shoplifted it, because even at that tender age you sensed the secret – books held it all – and reading books was more important than being well-liked or being able to shag flies in center field.

And you read it; and your reading was difficult because every once in a while you’d realize that you hadn’t been breathing, that this Wolfe person was so good at what he was doing you had forgotten to take care of even the unconscious business of systole-diastole. And when you finished reading that big novel, you sat back and savored the heat this Wolfe had put into you. Yes, this was what reading was all about! You had to have more, had to have periodic transfusions from this man’s supply of imagination.

One year earlier, 1951, just making a buck freelancing, Wolfe dipped merely a toe into the digest-sized-magazine (sf genre) with a remarkable novelette – “Self Portrait” in Galaxy magazine, and with rare good sense, foresight of literary “ghetto” imprisonment limitations (like Vonnegut, years later), scampered for dear life and a reputation in “the Mainstream.”

Yet despite Wolfe’s fleetness of foot, the rapid eye-movements of perceptive readers caught the slamming of the door, and having been dazzled by “Self Portrait” they began asking, “Who the hell was that?” They found out in 1952, when Wolfe’s first novel, Limbo, was published by Random House; and for the first time insular fans who had been cringing with talented dilettantes such as Herman Wouk sliding into the genre to proffer insipid semi-sf works like The Lomokome Papers, now had a mainstream author of stature they could revere. Preceding by almost twenty years “straight writers” like Hersey, Drury, Ira Levin, Fowles, Knebel, Burdick, Henry Sutton, Michael Crichton and a host of others who’ve found riches in the sf/fantasy idiom, Bernard Wolfe had written a stunning, long novel of a future society in purest sf terms, so filled with original ideas and the wonders of extrapolation that not even the most snobbish sf fan could put it down.

They did not know that six years earlier, in 1946, Bernard Wolfe had done a brilliant “autobiography” with jazz great Mezz Mezzrow, called Really the Blues. Nor did they suspect that in the years to come he would write the definitive novel about Broadway after dark, The Late Risers, or a stylistically fresh and intellectually demanding novel about the assassination of Trotsky in Mexico, The Great Prince Died, or that he would become one of the finest practitioners of the long short story with his collections Come On Out, Daddy and Move Up, Dress Up, Drink Up, Burn Up. All they knew was that he had written one novel and one novelette in their little arena and he was sensational.

In point of fact, the things science fiction fans never knew about Bernard Wolfe would fill several volumes, considerably more interesting than many sf novels. Of all the wild and memorable human beings who’ve written something, anything on which the “sf” label has been slapped, Bernard Wolfe is surely one of the most incredible. Every writer worth his pencil case can self-aggrandize on the dust jacket of a book that he’s been a “short order cook, cab driver, tuna fisherman, day laborer, amateur photographer, wrestler, horse trainer, dynamometer operator” or any one of a thousand other nitwit jobs that indicate the writer couldn’t hold a job very long.

But how many writers can boast that they were personal bodyguards of Leon Trotsky prior to his assassination (or prove how good they were at the job by the fact that it wasn’t till they left the position that the killing took place)? How many have been Night City Editor of Paramount News-Fawcett Publications, specializing in technical and scientific reporting? How many have been editor of Mechanix Illustrated? How many appeared in The American Mercury, Commentary, Les Temps Modernes (the French existentialist journal whose first director was Jean-Paul Sartre), Pageant, True, Esquire and, with such alarming regularity, Playboy? How many have worked in collaboration with Tony Curtis and Hugh Hefner on a film named Playboy (and finally, after months of hassling and tsuriss, thrown it up as a bad idea, conceived by madmen, programmed to self-destruct, impossible to bring to rational fruition)? How many were actually Billy Rose’s ghostwriter for his famous gossip column Pitching Horseshoes? How many writers faced the Depression by learning to write and composing (at one point with an assist from Henry Miller) eleven pornographic novels in eleven months (memorialized in his great semi-autobiographical novel Confessions of a Not Altogether Shy Pornographer)? How many have ever had the San Francisco Chronicle hysterically grope for a pigeonhole to clutch up some singular appellation of “Wolfe” in their own frustrated style and finally could helplessly only come up with “…Wolfe writes in a mixture of the styles of Joyce and Runyon …”?

Bernard Wolfe was not a “science fiction writer.” I am not a “science fiction writer.” We both have used the tropes of that genre to create memorable fiction. To my mind, Bernard Wolfe remains one of the most remarkable original writers of the 20th century.

Sherman Oaks, CADecember 2014

Excerpts of this Introduction originally appeared in Again, Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison®, (Garden City, NY, Doubleday, 1972) Copyright © 1972 by Harlan Ellison®; renewed 2000 by Harlan Ellison®. All rights reserved. Excerpts of this Introduction originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times (September 23, 1974) Copyright © 1974 by Harlan Ellison®; renewed 2002 by Harlan Ellison®. Harlan Ellison® is a ® registered trademark of The Kilimanjaro Corporation. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION TO LIMBO

by David Pringle

If Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four are the two great dystopian visions in modern British fiction, then Bernard Wolfe’s Limbo has some claim to being their closest American equivalent. Yet, curiously, it has failed to exercise that claim, either in the popular imagination or in the literary-critical consensus. I think it is a masterpiece, although I must admit that it has been a sadly neglected one. Perhaps its central image—of a near-future society in which men cut off their own limbs to prevent themselves from waging war—is too disturbing, too crazed, to make for ready acceptance. It is easier to imagine us succumbing to the ‘feelies’ and soma, or indeed to the everlasting boot in the face, than it is to project ourselves into Wolfe’s limbless, lobotomized world of 1990.

But what a grand cornucopia of a book Limbo is! It is big (413 pages in the Ace paperback edition), blackly humorous, and full of a passionate concern for the problems of its day—particularly the problems of war, institutionalized violence, and humanity’s potential for self-destruction. It is a novel which goes gloriously over the top, replete with puns, philosophical asides, satire on the American way of life, comments on drugs and sex and nuclear war, doodles and typographical jokes, medical and psychoanalytical jargon—a veritable Tristram Shandy of the atom-bomb age. In an afterword the author pays tribute to Norbert Wiener, Max Weber, Dostoevsky, Freud and, surprisingly, the sf writer A.E. van Vogt. ‘I am writing,’ he continues, ‘about the overtone and undertow of now—in the guise of 1990 because it would take decades for a year like 1950 to be milked of its implications.’

Bernard Wolfe (born 1915) earned a B.A. in psychology from Yale University, and for a short time he worked as a bodyguard to Leon Trotsky in Mexico, though he was not present when Trotsky was eventually assassinated. His first book, Really The Blues, was about jazz music, and he went on to write a variety of novels and non-fiction works. Evidently a man of parts. Except for a few short stories, Limbo remains his only venture into science fiction, yet it gives ample proof that he understood the form better than most. ‘The overtone and undertow of now’ is precisely the subject matter of all the most serious sf.

The plot concerns the travels and travails of Dr Martine, a neurosurgeon who in the year 1972 fled from a limited nuclear war to the haven of a forgotten island in the Indian Ocean. He has spent eighteen years there, performing lobotomies on the more antisocial of the simple natives (this is a humane continuation of the natives’ ancient practice of mandunga, or crude brain surgery). In 1990 Martine sets out to rediscover the world. He finds a partially destroyed North America in which the ideology of ‘Immob’ holds sway. In this grotesque post-bomb society men have their arms and legs removed and replaced with computerized prosthetics, in the belief that self-mutilation will prevent the recurrence of world war. It is a faulty equivalent of the islanders’ mandunga, the lobotomy which cuts away aggressive urges. Martine is horrified to discover that much of the inspiration for ‘Immob’ comes from a diary which he himself wrote and lost in that fateful year of 1972. He is the unwitting prophet of this nightmarish state; his jokes of eighteen years ago have been taken all too seriously. In any case it has all been in vain, for things are falling apart and a new war is about to begin. The story ends with Martine fleeing to his peaceful island as the bombs fall once more on the cities of America. It sounds grim and fatalistic, but in fact the novel is enormously funny and invigorating, and in the end holds out a kind of hope. Rich with ideas, all-embracing in its references, it is a book which uses the science and psychology of 1950 to grapple with the largest issues of our century. It is time that Limbo was recognized for what it is: the most ambitious work of science fiction, and one of the most successful, ever to come out of America.

© David Pringle, 1985

Since all the characters in this book are real, any resemblance between them and imaginary persons is entirely accidental.

Raymond Queneau

Part One

TAPIOCA ISLAND

chapter one

“MUCH PROGNOSIS today,” the old man panted.

The climb up the mountain was hard for him, several times he had to lean against the trunk of a raffia palm and try to catch his breath. With each halt he went through the same ritual of malaise. Removed from his head the green-visored tennis cap (found in a well-preserved Dutch sporting-goods shop in Johannesburg). Unwrapped from his emaciated middle a delicately figured silk paisley scarf (from the intact shelves of an excellent London haberdashery in Durban). Mopped brow with loincloth. Then reached down to massage his feet through the cricket sneakers (souvenir of the Cape Town country club, rescued from a locker which had belonged to the last naval attaché stationed at the British consulate there).

He knew he was not supposed to tax himself (“Without much care,” Dr. Martine had told him bluntly, “prognosis unfavorable”) but he would not take time out for a real rest, much less turn back. From his knobby shoulders hung the only native garment he could boast at the moment, a loose chieftain’s robe made of pounded bark and decorated with neat alternating rows of stylized parakeets and cacao flowers; he hitched it to his knees as he picked his way through the brush, arthritic ballet.

The jungle was noisy today, fidgety as an insomniac (he had been suffering from insomnia lately, Dr. Martine had been treating him for it), fronds rasped against each other, trees creaked, mynah birds shrilled nasal obscenities at the sun, marmosets jibbered in falsetto. He disapproved of this order of sounds, they were symptomatic of hyperthyroidism, hypertension, hypertonus. He frowned upon such tension, in Nature as in himself. Better to be like the slow loris, heavy-lidded, tapioca-muscled. Lately, though, he had been very tense.

Each time he interrupted his climb toward the Mandunga Circle he looked down in the direction of the village. Silly, of course, there was no chance of his being followed. As for the villagers, nobody was allowed to approach the Circle except the troubled ones and those who had business with them; and as for strangers, well, none had been seen on the island in his lifetime. Ever. None except Dr. Martine, Still, he kept looking back over his shoulder.

His intelligent deep-amber face, shining with sweat under a thatch of crinkly white hair, was fixed in a scowl now, muscles coagulated in ridges—welts left by some whip of woe. It felt as though he were wearing some sort of mask, he was not used to worry or the crampings of worry and the knots around his mouth and in his forehead quivered. Insomnia, bunched-up muscles, tremors, worry—it almost looked, he thought, as if he had developed some of the signs of the troubled ones. Unpleasant notion. He wished he had a bowl of tapioca, it relaxed the bowels.

“Mandunji most mild people,” he said half-aloud in English, remembering with irony a remark Dr. Martine had once made. “With us musculature rejects tonus like eye of owl rejects light. We sag very much, bristle never.” Immediately he corrected himself: “Are. The musculature rejects tonus like the eye of the owl.” It annoyed Dr. Martine to hear his language spoken without the silly, unnecessary words he called articles and verbs and so on.

A tarsier peered down at him from a branch and hiccupped dementedly.

A moment later, puffing hard, he had reached a small clearing on the crest of the mountain, bare except for a scattering of yuka and cassava plants. Memorable spot. Here was the center of the Mandunga Circle, here, eighteen and a half years ago, he had first set eyes on Dr. Martine. Looking down over the carpet of pinnate leaves thrown up by the raffias, he could see the saw-tooth cliffs on the perimeter of the island—island which by some miracle, Martine liked to say, had never been charted on any map by any cartographer—and the glinting waters of the Indian Ocean beyond. The sky was without a trace of cloud, a flawless impermeable blue—“as dazzling,” Martine sometimes said of it, “as a baboon’s ass,”

It was on just such a day eighteen years ago, as the sun was heaving up over Sumatra and Borneo (Martine insisted there were such places to the east: called them the islands of Oceania), that the doctor had been tossed out of the sky onto the mountain top. What more ominous bundles was that cobalt vacuum preparing to sprinkle over the island today?

“Tomorrow sunny and continued warm,” he said to himself, still in the doctor’s language. “Prognosis for weather, anyway, favorable.” Added, “The prognosis. For the weather. Is.”

Shading his eyes with a bony hand, he began to search the ocean for ships. It would be suicide, he knew, for mariners not familiar with these waters to attempt a landing anywhere on the island’s coast because of the treacherous reefs and the razor-backed cliffs which jutted out into the surf. Nevertheless, he looked. Ships could carry planes. It was possible these days for strangers to come by air as well as by sea. Dr. Martine had come by air.

Was that a vessel he saw, that speck on the horizon beyond which lay Mauritius and Réunion and Madagascar (places he had glimpsed only from thirty thousand feet up, on scavenging trips in Martine’s plane)? Out there in the direction of the forgotten trade routes which had once slashed this untonused old ocean? Way off to the west there, where if you traveled long enough you came at last to Africa, whose toppled cities were filled with fabulous paisley scarves and tennis caps, cummerbunds and opera hats and cricket sneakers, even crates of penicillin and electroencephalographs, and no people? The speck seemed to be moving, he could not be sure.

“No,” the old man said. “Otherwise, Doctor, prognosis not favorable.”

His features settled in a deeper frown, it felt like a hand grabbing his face. He re-entered the jungle to begin the descent on the far side of the summit, a galago dashed hysterically across the path.

In a few moments he reached the landmark, a tall column of scaly rock almost entirely overrun with creepers and ferns. Squatting in the thicket, he called out as loudly as he could, “Peace to all! Peace and long life. Open up, here is Ubu.” It was not English he spoke now but the throaty, resonant, richly voweled tongue of the Mandunji.

Facing him was a boulder which bulged out from the base of the rock, hidden from sight by a tangle of briers. It swung inward, briers and all. Stooping, Ubu stepped into the cavern.

“Peace to all,” he repeated. His hands went up in the ceremonial greeting, fingers extended and palms up as though a tray were resting on them, to indicate that their owner came without weapons and therefore in friendship and good will.

“Peace, Ubu,” the tall teak-complexioned young man at the gate answered sleepily. He yawned, a cosmic gape. Then he remembered the rest of the salutation and awkwardly stuck his hands out in turn. They were not empty; in one was a brush dripping red berry juice and in the other a sheet of pounded bark partially covered with rows of painted mynah birds and manioc plants. Apparently he had been working on this decorative drawing when Ubu arrived.

“I . . . do not mean . . . to offend,” he said slowly, searching for the words. It was dawning on him, Ubu could see, that he had committed a serious breach of etiquette by not emptying his hands before holding them out. “My thought is far away . . . I was making a design and. . . .”

Ubu smiled and patted him on the shoulder. At the same time he leaned forward to examine the scar on the young man’s shaved head, a ribbon of pink tissue which ran in an unwavering line from the forehead past both ears to the nape of the neck. It was the welt that was always made when the dome of a troubled one’s skull was sliced off with a Mandunga saw and then neatly pasted back in place.

“It heals nicely,” Ubu said, pointing to the scar.

“It has stopped itching,” the boy said.

“No more trouble there?”

The boy looked puzzled. “I do not remember the trouble people speak of,” he said. “Dr. Martine says I used to fight much . . . and there was much tonus in my muscles . . . I do not remember. Mostly I like to sit and draw birds and trees. I want to sleep all the time.”

“You are much improved, Notoa. I noticed just now that when you said, ‘Peace’ it was not just a thing to say, you meant it. The reports I hear from Dr. Martine are very good.”

“People say I used to fight,” Notoa said, looking down at the floor. “When I hear about it I feel ashamed. I do not know what used to make me hit my relatives.”

“You were troubled.”

Notoa regarded his hands with wonder. “It is very hard now even to make a fist, when I try it is a great effort and it does not feel right. Dr. Martine says the electric charge in my tensor muscles is down many points, he showed me on the measuring machine. Most of the time I am very sleepy.”

“Only the troubled are afraid of sleep.” Ubu patted the youngster again. “Speaking of Dr. Martine, where is he?”

Notoa yawned again. “In surgery. Moaga was brought this afternoon.”

“Yes, I forgot.” Ubu nodded and started down the corridor. Notoa swung the slab of rock to, and abruptly the rustling, crackling, croaking, twittering, twanging, twitching, ranting, jeering sounds of the jungle were cut off. In the sudden hush Ubu became aware of the throttled hum from the fans Dr. Martine had installed in camouflaged shafts overhead to pump a steady flow of fresh, filtered, dehumidified and aseptic air into the great underground hollow. The doctor liked to put his motors everywhere: on fishing boats, on the chisels and adzes used in hollowing out logs to make canoes, on stones for grinding maize, even on the saws for cutting skulls off. Such machines were not necessary, of course, they only took a man away from his natural work and made his mind and hands idle. One thing only was bad about this mechanization, it upset the routine. Because there were so many machines to do the work the young men now had much time to talk and study with the doctor and the old habits of work began to slip. The old habits made for a great steadiness, a looking in one fixed direction along a straight line. . . .

As he passed the row of cubicles, Ubu peered through the oneway glass on each door at the patient inside. Most of these Mandungabas were recent operatees, with tentlike bandages still on their heads, but some of them had had their dressings removed and were beginning to sprout new crops of hair over their scars. Ubu studied their faces as he went along, looking for signs of the tautness which had been a chronic torment for all of them before Mandunga. He knew what to watch for: narrowed eyes, tight rigid lips, corrugated foreheads, a hunched stiffness in the shoulder muscles—flexings of those who live in a world of perpetual feints and pounces.

No, there was no telltale strain in these once troubled people. If anything, their features and bodies seemed to have relaxed to the point of falling apart: heads lolling, mouths loose and hanging open, arms and legs flung like sacks of maize on the pallets. Well, a sleepy man does not break his uncle’s nose.

Beyond the cubicles was the large animal-experimentation chamber in which the tarsiers, marmosets, pottos, lemurs and chimpanzees huddled listlessly in their cages, most of them also wearing head bandages; beyond that, the laboratory in which most of the doctor’s encephalographs and other power-driven apparatus were kept; and finally, in the farthest corner of the hollow, the operating room. The window in this door was of ordinary two-way glass, Ubu could see that Dr. Martine was just slicing through the last portion of Moaga’s cranium with his automatic rotary saw.

What a sick one was this poor Moaga, Moaga the troublemaker, the sullen, the never-speaking, the vilifier of neighbors and husband-slasher. The riot had been drained from her body now, she lay stretched out on the operating table like a mound of tapioca (it would be nice to have some now), so completely anesthetized by rotabunga (would be nice to have some of that too) that although her eyes were wide open they could see nothing. She was naked and Ubu could see the tangle of wires that led from her arms, her legs, her chest, her eyelids, from all the orifices of her bronze body, to the measuring machines scattered around the room. He knew that in a few minutes, when Mandunga took place, the indicating needles on those machines would sink from the level of distress to the level of ease and Moaga’s sickness would be over, she would stay away from ganja (“marijuana,” in the doctor’s peculiar language) and eat more tapioca, take more rotabunga. Done with electric trepans and chrome-steel scalpels and sutures, or with an old-fashioned chisel driven by an old-fashioned rock, the result was always the same magic: the troubled one came out of it no longer troubled, only a little sleepy. When, of course, he did not die. It was true, fewer patients died since the doctor had introduced trepans and asepsis and anatomy and penicillin.

Dr. Martine inserted a thin metal instrument into the incision and pried; in a moment the skull gave and began to come away. An assistant was standing by with gloved hands held out, in spite of the surgical mask Ubu recognized him as Martine’s son Rambo. The boy took the bony cup, holding it like a bowl in the ritual of the tapioca feast, and immediately submerged it in a large tray containing the usual saline bath.

Despite the dozens of times Ubu had watched this ceremony, despite the hundreds of times he had performed it (at least the ancient rock-and-chisel version of it) himself in the old days, before Martine, he still felt a certain thrill at the sight of the brain’s crumpled convolutions—“those intellectual intestines, that hive of anarchy,” the doctor called them.

Suddenly Ubu thought of the black dot he had seen on the horizon: had it really been moving? Involuntarily his shoulders hunched and he sucked his lips in until they were thin and bloodless.

“You are lucky, Moaga,” he said, reverting to English. “Soon no more worries, prognosis good. But for some worries, no scalpel, prognosis very bad. . . .” This time he did not add the articles and verbs and so on.

chapter two

PULSE NORMAL, respiration normal: the rubber bladders through which she breathed clenched and unclenched in perfect rhythm, two pneumatic fists. Rambo trundled a large Monel metal cabinet over to the table, through its glass front a bank of electronic tubes glowed. Everything was in order.

From the machine, which contained an array of slender steel probes attached by coiled wires to the electronic circuits within, Martine selected a needle and brought it close to the exposed brain. He applied the point carefully to an area on the cortex, signaled his readiness with a nod, Rambo twisted one of the control dials on the machine’s operating panel. Moaga’s left leg shot up and twitched in an absent-minded entrechat. Another contact made the shoulders writhe, another doubled the hands into fists and sent them paddling in the air, a fourth set the teeth to grinding.

Now the doctor began the multiple stimulation tests, applying four, then six, then eight and ten needles simultaneously to various cortical centers; with the final flow of current Moaga’s face grew contorted, its muscles worked in spasms and her abdomen arched away from the table and began to heave. In spite of himself Martine felt his own abdominal muscles contracting, he always had this sympathetic response to the mock intercourse induced by a few expertly distributed amperes. “I got rhythm,” he said to himself.

He looked around the chamber. All his assistants were at their posts, watching their measuring dials and recording at each stage Moaga’s variations in temperature, muscle tonus, skin moisture, blood pressure, pulse rate, intestinal peristalsis, pupil dilation and eyelid blinking, lacrimation, vaginal contractions. Measure for measure. A measure operation. “Measure’s in the cold, cold ground,” he said under his mask. He was annoyed with himself for indulging in such nonsense but he knew he couldn’t stop it, luckily he was light of hand, sly of hand, sleight of hand, his fingers were so agile and dedicated that they did their job even under an avalanche of bad jokes from their massa in the cold cold groan.

Rambo wheeled away the machine and brought up a table, on it was a row of hypodermic needles filled with liquid. Strychnine. The next step was neuronography, strychninization, the firing of certain key areas of the cerebrum with this potent excitant in order to trace the pathways from the brain’s jellied rind to the hidden cerebellum, the thalamus, the hypothalamus. He made the injections expertly—but tensely: he was always tense with hypodermic needles—while his assistants jotted their scrupulous notations about the pursing of the lips, the fluttering in the cloaca, the squirmings of the pelvis.

While the strychnine bulleted through the brain’s maze and the indicators jumped, he looked down at Moaga’s face, down into the wide-open eyes which saw little and said much. Babbling eyes, ranting eyes. As always, the rotabunga drugs had induced a completely comatose state in which the eyes remained open; for almost nineteen years he had been performing Mandunga here in the cave and never once had he been able to turn his attention entirely from those open soapboxing eyes. What was it he always thought he saw in them? Icy accusation, glaciers of accusation.

Once the routine experiments were out of the way it did not take long for the actual surgery. First he put in place the fine surgical threads which marked the upstart areas on the patient’s frontal lobes, then he speedily made incisions along them and added several deft undercuts with the scalpel to free the spongy masses at the desired depth, then he removed these masses with a suction cup and quickly tied off the blood vessels. He reached down into Moaga’s throat and made her cough: no leakage from the sliced veins, everything in order.

Rambo returned with the Monel cabinet. The ten electric needles were applied to the same spots as before: the woman’s pelvic area remained inert, the vaginal indicators did not move. While Martine doused the exposed area with penicillin Rambo brought the skull and very soon it was back in place, the flaps of skin knitted together with stitches and silver clips.

Martine nodded and stepped back, beginning to strip off his rubber gloves. “Done it again,” he said to himself. “Goddamned Siamese twins. I’ve cut out the aggression, I’ve cut out the orgasm, can’t seem to separate the two. Sorry, Moaga. The pig-sticker did his best.”

Masseur in the cold cold groin. . . .

Martine looked up a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...