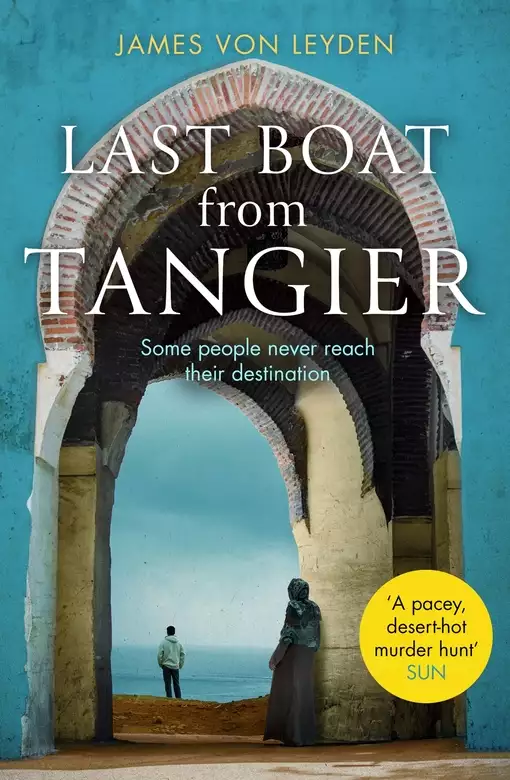

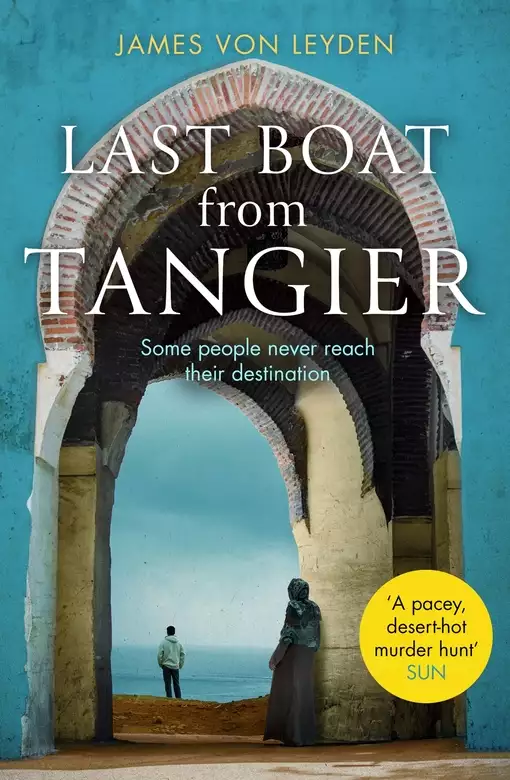

Last Boat from Tangier

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

When Detective Karim Belkacem's best friend and colleague, Abdou, goes missing during an investigation into an illegal cartel, Karim is sent to Tangier look for him. But the Tangier police have another problem on their hands. Thousands of sub-Saharan migrants have collected in the region, desperate to get to the Promised Land of Europe. Unable to trust his contacts in the police, or anyone in Tangier's underworld of traffickers and informants, Karim turns to his adopted sister Ayesha for help. The truth behind Abdou's disappearance is more disturbing than either of them could imagine.

Praise for James von Leyden:

'Clever, captivating and colourful; an absorbing thriller rich in atmosphere' Philip Gwynne Jones, author of The Venetian Game and Vengeance in Venice

Release date: December 10, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Last Boat from Tangier

James von Leyden

On the sports ground of the police college cadets were running around the track. It was Friday morning and the four hundred-metre race was their last activity before lunch. Among the male runners were two girls wearing the red tracksuits of the commissioner corps. One of them, short and slight of build, was neck and neck with the leader. As they came down the last straight she edged in front. Her legs were tired and oxygen fought to get to her lungs, but she had beaten boys before, racing down obstacle-strewn alleyways where the gaps were narrower and the bends were sharper and the ground was studded with metal drain handles and loose cobblestones … As she flew past the finish line the instructor jabbed his stopwatch.

‘Four-twelve, Talal! Four-thirteen, Hakimi!’

The man, his hair shaved close to his scalp like the other male cadets, stopped and stood with his hands on his knees, recovering his breath.

The girl went up to him. She had dark, intelligent eyes and a scar over her left ear.

‘Good race,’ she panted.

Instead of replying, the man spat on the ground then stalked off.

‘Take no notice, Ayesha,’ said the other girl as she came off the track. She took a breath then shouted at the man’s retreating figure: ‘Some people still haven’t come to terms with the fact that the college admits women!’

Aye sha Talal and Salma Mernissi were both twenty-two years old and room-mates at the Institut Royal de Police in Kenitra. Salma wiped her face with a towel while Ayesha took a drink from her water bottle. The instructor came over. He was a well-toned young man whose otherwise handsome features were disfigured by a broken nose. He picked up Ayesha’s tracksuit top and handed it to her with a smile.

‘Well done.’

As they walked off, Salma made mischievous eyes at Ayesha. Ayesha laughed. ‘What?!’ She flicked Salma with her tracksuit top.

Laughing and joshing, the girls made their way across the parade ground, past cadets marching in formation. They discussed arrangements for the weekend.

‘Are you going to stay for lunch?’ asked Salma.

‘No. A quick shower and I’ll be off. I told my mother I would be home by seven. The neighbour is making couscous.’

‘Don’t forget we have a class on Cri tical Incident Management on Monday.’

‘I’m taking my notes.’ Whether I look at them is another matter.

‘I’ll test you when you get back!’ Salma wagged a finger. ‘No excuses!’

Their voices echoed across the foyer of the accommodation block. It was a modern, three-storey building with female quarters at one end. The girls walked down the corridor and Salma unlocked the door of their bedroom. The room was compact: two single beds with wardrobes at their foot and a desk between them. Salma untied her ponytail and threw herself on her bed while Ayesha went off to shower and change. A few minutes later she reappeared in a black trouser suit and took her overnight bag from the wardrobe.

‘There’s still time to get a weekend pass if you’re quick.’

‘I have to finish my essay. Another time, inshallah.’

Ayesha looked at her room-mate with admiration. She didn’t have Salma’s aptitude for study. But the fact that her grades were almost as good as Salma’s was proof that the Royal Institute measured success by ability on the assault course and shooting range as well as in the classroom and laboratory.

As the call to prayer rang out, Ayesha joined a stream of cadets heading to the gates – dressed, like her, in the off-duty uniform of dark suit, white shirt and black tie. One by one they collected their mobile phones at the gatehouse. The rules about mobile phones were strict. As the principal told them on their first day, the cadets were there to become officers, not to check their Facebook status. Under no circumstances were phones to be brought into the college. They had to be handed in at the gatehouse on arrival and signed out on departure. With every aspect of their lives regimented from six in the morning until ten at night it was little wonder that the cadets laughed and joked and called their loved ones as they streamed out of the gates.

Ayesha stood at the roadside and put her hand out. A petit taxi pulled up.

‘The station,’ she said, getting in.

Ayesha’s heart always skipped a beat when she took a taxi. But the driver, a young man in a green jellaba, seemed pleasant enough, and the Quranic chanting on his radio was reassuring.

In common with other Moroccans who worked or studied, Kar im Belkacem and his sister Khadija returned home for their midday meal. In Karim’s case it meant a fifteen-minute scooter ride from the police commissariat near Marrakech’s Jemaa el Fna to the family riad at the northern end of the medina. Today was a warm spring day and the swifts were soaring and screaming as Karim parked his moto. He walked into the courtyard and looked up at the railings on the second storey of the house, as if searching for something. Then he draped his jacket over the disused fountain, removed his shoes and entered the salon.

The room was long and narrow with a high ceiling and a shelf unit on which stood a forty-six-inch television. Karim greeted his mother and sister, sat down at the low table, dipped his fingers in couscous and turned his attention to the television. His mother, Lalla Fatima, had bought the television shortly after Karim’s father died, and it was always switched on during mealtimes – an intrusion, Karim thought wryly, that his father would never have allowed. Khadija liked to catch the morning chat shows before she went to work and never missed the soaps at lunch and dinner.

Like Karim, Khadija had a slender nose and the green, almond-shaped eyes of an Amazigh, or Berber, from the Chleuh tribe of southern Morocco. But good looks were all they shared. Khadija was not ambitious, content to earn a meagre salary as secretary for a law firm. She had put all her efforts into attracting a rich husband. Since the engagement fell through, two years ago, she had lost interest in her appearance. Her cheekbones had lost their definition and she wore baggy track bottoms to hide the fact that she had put on weight.

‘Khadija!’ Lalla Fatima said sharply. ‘Your brother is home.’

With a sigh, Khadija flicked to the news channel. The news shows were the only programmes that Karim watched. He followed Al Jazeera as intently as Khadija followed her soaps. A police officer – so Karim believed – should know what was going on in the world. How else was one to make sense of a new edict from the government or understand the joblessness that drove a man to steal?

On that Friday lunchtime the news channel carried a report about a mass assault on the Ceuta border which had taken place the previous night. The footage made uncomfortable viewing. Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa were trying to scale a six-metre-high fence topped with razor wire while commandos from the Moroccan police attempted to pull them down. On the Spanish side the Guardia Civil were trying to repel the invaders with high-pressure hoses. One young African in a sodden khaki jacket and woollen hat had managed to make it over the wall. He was running around making victory signs at the cameras while the Guardia Civil chased him.

‘Why’s he so cheerful?’ asked Lalla Fatima. ‘They’re going to catch him, for sure!’

‘Ceuta is part of Europe,’ Karim answered between mouthfuls of couscous. ‘Once a migrant makes it into Ceuta they can claim asylum. They can go anywhere in Europe, get a job, bring their families.’

‘Ha! Did you see that?’ Khadija pointed. ‘That guy who fell? The police are giving him a kicking!’

Lalla Fatima was appalled. ‘There’s blood coming from his head! I can’t bear to watch!’ She reached for the remote control.

‘Bletee! Wait!’ Karim stayed her with his hand. He was both fascinated and repelled by what he saw. The operation was a free-for-all, the police pouncing on any Africans who fell to the ground and beating them with batons. Such aggressive behaviour reflected badly on the Sûreté. It certainly compared unfavourably to the more disciplined approach of the Spanish Guardia Civil.

Lalla Fatima put aside the remote. ‘Where do they come from, Karim, all these migrants?’

Karim had seen reports of King Mohammed VI making official visits to other African capitals, but beyond Niger the countries seemed to merge into one another. He shrugged his shoulders. ‘I don’t know.’

‘The Afaraqa are not like the Syrians,’ Khadija declared. ‘The Syrians have got a reason to flee. There’s a war going on in their country. The Afaraqa just want fancy cars and houses – stuff they’ve seen on television. They should stay at home and get a job!’

‘Shh! I’m trying to listen.’

Khadija persisted. ‘Have you seen the blacks begging at the traffic lights? The women with babies on their backs? I never give them anything. We have our own beggars to look after!’

‘When did you last give money to a beggar?’

With an exasperated sigh, Karim turned up the volume. It nearly drowned out the sound of the telephone that was ringing from the courtyard. But the phone kept ringing and Khadija went out to take the call. She returned a few minutes later.

‘That was Ayesha. She’s coming to Marrakech this weekend.’

Lalla Fatima’s face lit up. ‘God be praised!’

‘She’ll visit us on Sunday morning, inshallah.’

‘With Lalla Hanane?’

Khadija shook her head. ‘You know how frail Hanane is.’

Lalla Hanane was Ayesha’s birth mother. She had given birth to Ayesha in a remote mountain village during a cholera epidemic. With her husband out of work, and two other children to feed, Hanane had been forced to give up the infant for adoption. The Belkacems took Ayesha in and brought her up alongside their own children. At the age of twenty, Ayesha was reunited with her mother, now living on her own not far from the Belkacems. Ayesha took her duties as a daughter seriously. She returned from police college to do the housework and keep her mother company. But what she enjoyed most was visiting the Belkacems, where she could relax and gossip like in the old days. I have two mothers, she told Salma. With Lalla Hanane I can be a daughter. With Lalla Fatima I can be myself.

Karim was too absorbed in the television to pay attention. It was only when he was getting ready to return to work, and Khadija was grumbling about having missed her favourite Turkish soap opera, that he registered that Ayesha was coming to see them.

Riding back to the commissariat, Karim was in two minds about Ayesha’s visit. He wanted to see her but he also dreaded the prospect. This conflict was not new.

As a boy of four, Karim had been entranced by Ayesha’s arrival in the Belkacem household. He dangled toys and sang songs to her while ignoring his sister of the same age. He wondered at her fierce determination to walk, her precociousness in mastering the stairs. When he started running around with the other boys from the neighbourhood he brought Ayesha with him. At first the other boys were grudging. In time, however, Ayesha’s fearlessness and penchant for mischief won approval. She was always the one who took the greatest risks and ended up in the most serious scrapes. When the boys took turns to steal mandarins on market day she vanished into the crowd, returning a few minutes later staggering under a watermelon. She didn’t do it to impress the other boys. She did it for Karim.

When Karim was sixteen and Ayesha thirteen their relationship took a different turn. They met after school to share gossip, jokes, dreams, observations, feelings, secrets. Sometimes these trysts took place at the nearby flea market of Bab el-Khemis. Or they chatted on the roof of the riad, which they had made their private domain. Karim would gossip to Ayesha as she hung out the washing. He would help her with her homework or they would lie together on the old mattress, Ayesha’s head on Karim’s chest, and talk about spending their lives together.

Ayesha and Karim regarded each other like cousins. But they were brother and sister in the eyes of Islam. Any intimacy, any closeness, was forbidden. This caused Karim endless torment. He moved away to police college and embarked on relationships with other women. Ayesha, too, moved out to her mother’s house and then to police college. But they couldn’t avoid meeting occasionally and when they did there was a pull, an attraction, that made it hard for Karim to concentrate on anyone or anything else. The day would come when Ayesha married another man but until then, Karim decided, any encounter with her was best avoided.

The first thing he saw when he arrived at the police station was Bouchaïb, the parking attendant, leaning on his crutch and grinning.

‘Only three hours until the match, Mr Karim!’

‘What match is that?’

‘Raja are playing Wydad. It’s going to be close but I think Raja will win! They won against Tunis last week!’

Karim had no interest in football and he didn’t pretend otherwise. He walked up a flight of outside steps to his office. He shared the room with two other officers. One was his deputy, Abdou. For the past eighteen months they had been collaborating on an investigation into fake medicines: poor quality copies of life-saving drugs bought by patients who couldn’t afford the real thing. The other officer was Noureddine, a senior commander who presided over the two young lieutenants like a stern uncle. As Karim entered he was surprised to see Noureddine talking to the station superintendent.

‘Salaam ou-alikum!’

The superintendent’s voice was grave. ‘The Tangier police just called me.’

Karim nodded warily. As part of their investigation he had sent Abdou to help at the port of Tanger-Med.

‘Abdou’s gone missing.’

Alarm bells rang in Karim’s brain. The Chinese cartels who manufactured fake drugs were known to be vicious. Many had switched from narcotics trafficking to fake drugs because the risks were lower and the profits greater.

‘How long?’

‘Three days.’

‘His mobile …?’

‘Not responding.’

It was Noureddine’s turn to speak. ‘Tomorrow is Saturday. If Abdou hasn’t surfaced in the next twenty-four hours you’re to leave for Tangier on the night train.’

On Saturday morning a young black man arrived outside the north-eastern corner of Tangier medina. Called Bab Dar Dbagh, The Gate of the Tannery House, the corner was perfect for a selling his wares. The position was elevated with a view over the harbour. No one harassed him, there was a ledge to sit on and an attendant let him use the nearby lavatory free of charge. After checking that there were no police around, Joseph opened his Adidas bag and took out twenty pairs of sunglasses. He arranged them on the ground in two neat rows with the wings of the glasses extended. Next, he took out five telescopic umbrellas and placed them next to the sunglasses. Rain or shine, he would make money.

Unfortunately, today was neither sunny nor rainy. It was one of those cold spring days in Tangier when the sun struggles to penetrate thick banks of cloud. For the first two hours few people came past. After disembarking from the ferry most tourists went up to the medina by one of two routes: Port Gate or Tannery House Gate. Today they all seemed to be using Port Gate. Joseph didn’t mind. He was happy gazing at the harbour. He watched a gendarme wander out of his hut on the quayside, light a cigarette and check his mobile phone. On the boulevard, a couple strolled arm in arm then stopped to look at the hoardings for the new marina. Between the marina and Tannery House Gate was a large car park where two men washed cars. With hundreds of motorists using the car park the men had more work than they could handle. A few weeks ago an impatient motorist asked Joseph to wash his Peugeot 305 using a standpipe and an old sponge. Joseph cleaned the car from top to bottom but all he got for his efforts was a parting jeer. Bslemma, azzi! So long, nigger!

The advantage of selling sunglasses and umbrellas was that no one could cheat him. He decided which items to sell and how much to charge. He favoured cheap goods that everybody wanted and that he could scoop up in five seconds if the police arrived.

As the sun came out the air became warmer and the road grew busier. Joseph laid out another five rows of sunglasses: Ray-Ban, Giorgio Armani, Gucci, Cartier. At three o’clock, the ferry arrived from Tarifa. Shortly afterwards groups of day trippers came walking past. A Spanish girl stopped to buy a pair of Ray-Bans for two euros.

Out at sea, he could see a white line of breakers. Joseph knew all the moods of the sea: the glassy surface on a calm evening, the metallic glint that presaged a change in weather. He wondered what had happened to his neighbour who left the camp a week ago. He had promised to send Joseph a text. Perhaps he’d got his phone wet. Salt water was bad for mobiles, everyone knew that. You could wrap your phone in three layers of plastic but once it came into contact with the sea, all bets were off. Joseph reached in his pocket and felt the reassuring outline of his Samsung. He’d taken it to the shopping centre that morning and managed ten minutes’ charge in a floor socket before he was chased away by a security guard.

There was the ferry, going back to Tarifa. Tarifa sounded like a nice place. Sandy beaches and fancy restaurants. Maybe his neighbour from the camp was sitting at one of them right now with a big grin on his face.

Catching the Saturday night train to Tangier had one benefit: it gave Karim an excuse to avoid seeing Ayesha. The train was busy, and there was a crying infant to contend with, but at least he had a seat and the overhead lights weren’t too bright. As the night wore on the warmth drained from the carriage and he put on his jacket. The old woman sitting opposite was snoring, a drool of saliva on her lower lip.

Unable to sleep, Karim played games on his phone. Abdou always used to pass the time with puzzle books and Karim was annoyed with himself for forgetting to buy a sudoku book at the station. When his eyes started hurting he gazed through the window. They were crossing the Doukkala plains: mile after mile of moonlit wheat fields interspersed with sleeping hamlets.

Karim cast his mind back to eighteen months ago, when he and Abdou had first uncovered the counterfeit drug trade. They found that antibiotics, painkillers, heart drugs and cancer medications – drugs whose high price put them beyond the reach of everyone but the well-off – were being copied by Chinese factories and shipped into the Maghreb by the container-load. In many cases, the fake drugs contained nothing more than glucose. Sometimes they were cut with harmful substances like rat poison.

Under normal circumstances Karim would have handled the Tangier assignment himself. But because he had sidelined Abdou from a previous operation in Agadir, and felt he owed Abdou a favour, he gave the job to him. Going north would be an adventure, he told him. Tanger-Med was the biggest and most modern port in Morocco. Abdou could check out the latest scanning and logistics technology. He could impart his knowledge to the Tangier authorities and earn their gratitude in return.

It was only on Friday afternoon, when he learned of Abdou’s disappearance, that Karim looked more closely into events at Tanger-Med. Since 2011, seizures of fake drugs had risen steadily. Then, about six months ago, the seizures tailed off. In December – the last month for which statistics were available – there hadn’t been a single confiscation. The authorities were still seizing heroin, guns and other contraband. Just not fake medicines.

Karim hoped that there was a simple explanation for Abdou’s disappearance. Perhaps he had gone undercover to monitor security procedures. God willing, Abdou would be waiting for him at headquarters on Monday morning, smiling broadly and asking for the latest gossip from the precinct.

‘Qahwa?’ The old woman opposite was holding out a thermos flask and a cup of coffee.

‘Thank you,’ said Karim. The coffee was sweet and milky.

‘Dar Bida? Are you going to Casablanca?’ The woman’s skin was as wrinkled as a walnut. A strand of grey hair straggled out from her headscarf.

‘Tangier.’

‘Tanja?’ The woman flinched slightly.

‘Yes.’

‘Your first time?’

Karim nodded.

The old woman leaned forward and wagged a bony finger. ‘A beautiful city. But a dangerous one.’

Karim laughed.

The woman sipped her coffee and gazed at him silently.

‘Don’t worry, a lalla. I’m a police officer. I’ve been all over the Maghreb.’

‘Tangier is not like the Maghreb.’

‘How so?’

The woman stared at him for a few more minutes. ‘People get lost there.’

Karim laughed again but his laughter died on his lips as he realised that this was precisely the reason why he was going to Tangier. The woman’s eyelids closed and she fell asleep, the flask still in her hand.

It was Sunday morning and Ayesha was at the Belkacems playing with Safee, the pet monkey. Safee had lived an eventful life. As an infant he earned a profitable income for his owner by climbing on the shoulders of tourists in Jemaa el Fna. When he proved more interested in yanking earrings than posing for photographs, Safee was sold to a Frenchman who gave him as a gift to his girlfriend. The monkey escaped from the girlfriend just as she was about to get rid of him and turned up one night on the Belkacems’ roof, where he was adopted by Ayesha. The family dubbed him Safee – ‘enough’ – because he was always causing mischief. Safee, come down here; Safee, give back the remote control; Safee, leave the bird food alone. Karim had a wooden cage made for him, but Safee preferred to clamber up the railings and observe proceedings from on high. When Ayesha moved out to live with Lalla Hanane the responsibility for looking after Safee fell to Khadija, a duty which she resented.

‘I brought some cooked chicken as a treat,’ said Ayesha, taking out a food storage box.

‘You needn’t have bothered,’ Khadija snapped. ‘He gets leftovers every night.’

‘He opens the bin and eats the vegetable peelings,’ sighed Lalla Fatima. ‘It won’t be long before he can open the fridge.’

Ayesha gave a laugh, swinging Safee from her shoulder and placing him on her lap. ‘You’re a clever little rascal, aren’t you?’ She nuzzled his forehead. ‘When I’ve finished college you can come and live with me, God willing. Until then, you have to be a good boy and not annoy Khadija!’ She looked around the courtyard. ‘Where’s Karim?’

‘In Tangier.’

‘What’s he doing there?’

‘Looking for Abdou. The poor boy has disappeared.’

Ayesha knew Abdou well. He had been a frequent dinner guest at the riad in the old days. Once, on the way back from a summer outing to Ourika, where Abdou’s family lived, Lalla Fatima declared that Abdou would make a fine match for Ayesha; a comment that caused Ayesha to laugh and Karim to bite his lip and change the subject.

‘Was he on an Operation MEDIHA assignment?’

‘Operation what?’

‘You know – the fake drugs investigation that Karim set up with the gendarmerie and the customs authorities.’

‘Yes, he was, poor boy. But Karim is sure he will track him down, inshallah.’

Despite Lalla Fatima’s words Ayesha was sure that Karim would be worried. Any missing officer case was cause for concern. And Abdou wasn’t just any officer: apart from herself and Lalla Fatima, he was the person that Karim felt closest to. On every level the disappearance was disturbing. How annoying, therefore, that Karim had already left for Tangier! They could have taken the train together as far as Kenitra and discussed the case.

‘Come, tell us, Ayesha,’ said Lalla Fatima, ‘what marvellous things are they teaching you at college?’

‘Meema, really! Anyone would think that Karim hadn’t been to the same college!’

‘Yes, but you’re a woman! Remind us how many female cadets there are.’

‘Five.’

‘And how many men?’

Ayesha laughed. ‘Nine hundred.’

‘Five women and nine hundred men! Imagine that!’

‘Stop, Meema. You’ll make her blush.’ Khadija envied the fuss that her mother made of Ayesha. It should have been her returning to the riad to show off her newborn ba. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...