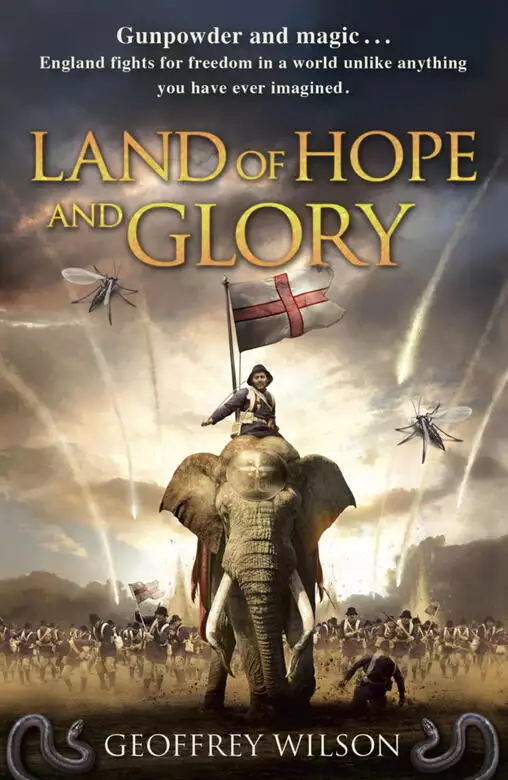

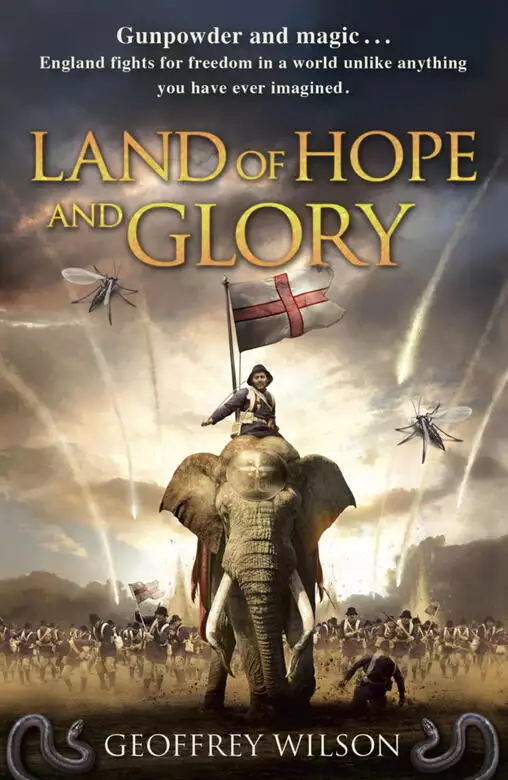

Land of Hope and Glory

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

It is 1852. The Indian empire of Rajthana has ruled Europe for more than a hundred years. With their vast armies, steam-and-sorcery technology and mastery of the mysterious power of sattva, the Rajthanans appear invincible. But a bloody rebellion has broken out in a remote corner of the empire, in a poor and backward region known as England. At first Jack Casey, retired soldier, wants nothing to do with the uprising, but then he learns his daughter, Elizabeth, is due to be hanged for helping the rebels. The Rajthanans offer to spare her, but only if Jack hunts down and captures his best friend and former army comrade, who is now a rebel leader. Jack is torn between saving his daughter and protecting his friend. And he struggles just to stay alive as the rebellion pushes England into all-out war.

Release date: September 15, 2011

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 340

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Land of Hope and Glory

Geoffrey Wilson

Harold Neary flinched at the first crack of a musket. A bullet whined past in the dark. Then another. But Harold spurred his horse on towards the line of soldiers who stood ahead in the gully.

Tonight he would kill Rajthanans. Nothing would stop him.

The Sergeant Major – riding beside Harold – drew his scimitar and shouted, ‘Charge!’

Harold and his eight other comrades lifted their swords too and roused a cry somewhere between a cheer and a shriek. They thundered down, the musket flashes rippling before them, the bullets thickening.

Harold gripped his scimitar tight as he rode. His heart flew, but there was no need for fear. God was on his side.

He thought of his brother, who had died fighting the Indians – the Rajthanans. Those heathens thought they were so high and mighty, the lords of England, but Harold would teach them that they couldn’t lord it over him. When he’d served in their army, they’d shouted at him, flogged him, practically starved him, but he’d survived. And while he still had strength he would slaughter as many of the bastards as he could.

Cloud covered the moon and in the faint light Harold could barely see the scattered row of forty European soldiers – only their faces and hands stood out. Their fingers, like fireflies, darted to ammunition pouches, lifted cartridges, slammed ramrods down barrels. Grey powder smoke drifted along the line. Behind stood Rajthanan officers in silver turbans that brightened at each firearm spark.

And further back rose the bone-white tower of the sattva link, shining slightly against the black background of the hills.

Bullets hissed around Harold. With a metal scream, one struck a scimitar. To Harold’s left, young Turner cried out and jerked back off his horse.

Turner. Down. That left just nine riders.

‘Steady, men!’ the Sergeant Major shouted.

Harold glanced at his commander. The Sergeant Major was a big man with broad shoulders and thick arms. In the grey light his face was like battered tin: his nose crushed, his ears mangled and his shaven head pocked and dented by old injuries.

He was a great man, the Sergeant Major, and one of the toughest soldiers Harold had ever met. It was the Sergeant Major who had convinced them all to don peasant clothes and take to the hills. It was the Sergeant Major who had taught them how to fight the Rajthanans, how to burst out of the wilderness and attack before anyone knew what was happening, and then vanish again as quickly as they had appeared.

Harold would follow the Sergeant Major anywhere.

The enemy were near now. The Europeans stopped firing, clicked the catches on their weapons to release their knives, and formed a line of pointed steel. Their faces were set hard beneath their blue cloth caps and the brass buttons shone on their blue tunics. Harold had worn a uniform like that for three years. He’d fought for the Rajthanans just like these men. But no more.

The Rajthanan officers screamed for their men to hold steady.

Harold remembered hearing the news that the Rajthanans had murdered his brother and then he was shouting so hard his throat ached and the sound seemed to blot out everything else, save for the wind whipping past and the undulating movement of the horse.

He swerved and aimed for the nearest officer. For a few seconds he could see his opponents in great detail: wide eyes, teeth, nostrils. It was like a dream.

Then his horse jumped and the soldiers dived. He swung his blade, hitting nothing. He couldn’t see the officer. He heard hooves nearby colliding with heads and chests. Scimitar chimed against knife-musket.

And then he was through. He glanced about, and saw that none of his comrades had fallen and their pace had hardly slowed.

‘To the tower!’ the Sergeant Major bellowed.

Harold wanted to stay and fight, to get his first kill, but he had to keep up.

The windowless, two-storey tower loomed ahead in the narrowest point of the gully. A twenty-foot-high brass rod topped the pointed roof.

Away to the right, a set of tents came alive. Soldiers stumbled out in their underclothes and almost fell over as they pulled on their trousers. They came running up the slight incline in their nightshirts, baying like dogs. Harold could make out snatches of what sounded like Andalusian.

The Sergeant Major shouted to Harold and pointed towards the tower. Harold followed his leader over to an arched entrance and leapt from his charger. He released a sack hanging across the back of the horse, then humped the heavy weight on to one shoulder.

The Sergeant Major glanced at him. Harold grinned, patting the sack. Within that cloth was something worth more to him right now than gold.

Powder.

The Sergeant Major went first up the circular stone stairway, drawing an ornate, multi-barrelled pistol from his belt. It was dark, save for a trace of misty light from above.

Harold breathed heavily and his heart whispered in his ears. He shook the long hair out of his eyes.

Near the top of the stairs they paused. Above them was an archway, out of which floated the faint light.

‘Anyone up there?’ the Sergeant Major called. ‘Give yourselves up and we’ll spare you.’

No response.

Harold heard shouting and pistol shots outside. His comrades would be fighting off the soldiers. There wasn’t much time.

They advanced up the stair.

With a sudden high-pitched cry, an Indian officer charged through the arch, stumbling down the first few steps. He fired his pistol straight at the Sergeant Major. The hammer clicked—

Nothing happened – a misfire. The officer’s face dropped.

The Sergeant Major smiled, his pistol cracked and smoke blurred the stairwell. The officer’s left cheek flared open and spat blood against the wall; the white row of his teeth was visible inside the wound, as though he were smirking. He fell forward, clattered and jerked on the steps.

‘Good shot, sir,’ Harold said. Another heathen dead.

The Sergeant Major grinned, his eyes quivering in the dim light. ‘Any more up there? Give yourselves up.’

Silence.

They crept up the remaining steps. The Sergeant Major pressed himself against the stone wall, then swung into the entrance, holding the pistol before him.

Nothing happened.

He looked down at Harold. ‘There’s no one.’

Staggering under the weight of the sack, Harold ran up the stairs and entered a stone-walled room lit by pale yellow lanterns. To one side, on top of a pedestal, stood a spherical wire cage, within which squatted a metal shape that looked like a creature dredged from the sea. Numerous crab-like claws hung from its sides and a mass of mandibles and feelers covered its head.

Harold stopped dead and made the sign of the cross. That thing was one of the Rajthanans’ devils. Avatars they called them.

The Sergeant Major stared at the device and rubbed his hand over his shaved head. He shot a look at Harold and nodded.

Harold took a step towards the machine, noticing a copper cable leading from the thing’s back, across the floor, along one wall and up through the centre of the ceiling.

The avatar moved. One claw scraped along the bottom of the cage and a feeler lifted.

Harold hesitated. He’d heard the Rajthanans fed these beasts on human blood. Whether that was true or not, he’d like to see them all smashed to pieces as soon as the Rajthanans were kicked out of England. The country was in the grip of black magic and only the crusade would free it.

‘Hurry up,’ the Sergeant Major said. ‘It’s harmless.’

Harold swallowed. He stepped up to the pedestal and heaved the sack to the floor. The avatar moved more rapidly, scuttling about in the cage and snapping its claws.

Harold pushed the hair back from his eyes, struck a match and lifted the fuse sewn into the side of the sack. He looked up at the avatar, which was now scratching frantically at the bars and making a clicking noise, as if it knew what was coming.

Harold smiled and lit the fuse. The flame settled into a red glow that crept up the hemp cord.

‘Let’s go,’ the Sergeant Major said.

They charged down the stairs and came out in the middle of a melee. Only six riders remained – one more had fallen. At least fifty soldiers ran about the horses and jabbed with their knife-muskets. The riders slashed left and right with their scimitars and continually circled to avoid being struck. Pistol shots rang out intermittently and Harold caught the sulphurous scent of powder smoke.

Two soldiers lunged with knife-muskets as Harold came out of the entrance. The Sergeant Major skipped to the side and dashed his opponent’s head against the wall, but Harold moved more slowly. He saw the gleaming blade rush towards him and strike him in the shoulder. His arm went cold as the knife grated against bone. He gasped and fell back against the tower, the knife still stuck firmly and the soldier still holding on to the musket.

Harold locked eyes with the European soldier. The man’s face was twisted with battle fury and he was panting so hard Harold could smell his stale breath.

‘Bastard heathen,’ Harold managed to say, and spat in the soldier’s face.

Then the Sergeant Major roared and punched the man on the side of the head. The soldier stumbled sideways, his round cloth hat flying off. The musket slipped out, tearing an even greater wound in Harold’s shoulder.

Harold shivered. He could see the Sergeant Major kicking the fallen soldier in the face, but the scene was becoming blurry and strange.

He had to stay awake. He couldn’t let the heathens beat him.

‘You all right?’ The Sergeant Major was suddenly standing before him.

Harold nodded. Sickness welled in his stomach and his arm was like ice. He shuddered and stumbled, but the Sergeant Major caught him and helped him up on to the nearby horse.

The Sergeant Major then swung himself up behind and fired his pistol in the air. ‘Knights, ride!’

Harold felt the charger galloping. He slumped forward against the animal’s mane and clung on as tightly as he could with his one good arm. His six remaining comrades bounced along to either side, stray musket and pistol fire flying after them.

Something was wrong. Grimacing at the pain, he looked back and saw that the tower was still standing. Had the fuse gone out? Had the heathens found the powder sack?

Then the top storey of the tower blossomed into a red and yellow flower that lit the whole valley for a moment. A baritone pulse rushed out and rippled through his bones. Chunks of stone whistled in the dark and soldiers scrambled for cover. The horse stumbled slightly, but didn’t fall.

Harold smiled. That was for his brother.

The Sergeant Major lifted his fist in the air and gave a defiant cheer. The other riders joined him.

But their celebration was cut short by the sound of shots from the darkness off to the left. Around a dozen horsemen were riding from the camp and bearing down on them.

‘Hurry, knights,’ the Sergeant Major shouted, and they spurred and slapped their horses onward.

They turned into the trees at the end of the gully and the horses scrambled over an embankment. Then they sped on through the mottled gloom of the forest. Branches and leaves leapt in front of them. Shrubs appeared and disappeared like clouds of dust. The horses whinnied and rolled their eyes.

Every jolt sent a wave of sickness through Harold and he could hear himself groaning.

After what seemed a long time, they came out on to a grassy slope. They zigzagged up, the horses skidding and kicking up clods of earth. They took around ten minutes to reach the summit, where they paused and looked down.

Harold blinked. The cloud had lifted now and he could see a wide sweep of the countryside rolling away in great folds and buckles, like the ocean at night. The knots of forest, indistinct valleys, open hills and heaths were all powdered by the moon.

‘Down there,’ hissed Smith, pointing to the line of trees they’d left earlier.

Harold could just make out the enemy cantering along beside the woods several hundred feet to the left.

The Sergeant Major snapped open a spyglass and followed the horsemen for a moment. ‘Must have lost us in the forest. Don’t think they’ve seen us yet. Come on.’

They turned and galloped down a short slope before reaching a further stretch of trees. They followed a track that wound through the undergrowth, leaves slapping against the horses’ sides.

Harold felt himself slipping away, then shook his head and managed to pull himself back.

After a few minutes, the Sergeant Major called a halt, dismounted and walked to the rear of the group.

Dizzy with pain, Harold looked back over his shoulder and watched as his leader sat cross-legged on the ground, rested a hand on each knee and closed his eyes.

The Sergeant Major breathed slowly and deeply. Apart from the rise and fall of his chest, he was still. The sound of insects swirled and an owl hooted in the distance.

Then Harold noticed the faint, sweet scent of incense – the smell of sattva, that mysterious vapour the Rajthanans used for their machines and avatars and unholy powers. He was leery of it, as he was of all the Rajthanans’ devilry, but the Sergeant Major had some skill with it, and Harold had grudgingly come to accept that it had its uses.

Sometimes you had to fight black magic with black magic.

Harold’s comrades shifted in their saddles – they were just as nervous of sattva as he was.

The Sergeant Major blew gently and a strange breeze seemed to emanate from his body and flow back along the path with a hiss. But it wasn’t so much a breeze as a warping of the scene itself. Tree trunks, branches and the leaf-littered ground all rippled, as if reflected in a pool of water into which stones have been cast. Slowly, the horse tracks on the path disappeared, as if sinking into the earth. The twigs and small branches that had snapped as the horses passed, regrew. The wind rose in strength and then faded, the whorls and eddies subsiding. All evidence that the riders had been there had now vanished.

The Sergeant Major stood, chuckled and rubbed his hands together. He walked back to his charger and said to Harold, ‘You still with us?’

Harold tried to speak, but couldn’t form the words. He grunted as he fought back the vomit stinging his throat.

‘We’ll get you back soon.’ The Sergeant Major mounted and looked across at the riders. ‘Well done, knights. Our land is in darkness, but our crusade will bring light. God’s will in England.’

‘God’s will in England,’ the others said in unison.

As they moved off, Harold felt as though the night were thickening and suffocating him. If he drifted off he was sure he would die. And yet he had to stay alive to keep up the fight against the Rajthanans.

The pain in his shoulder seemed to be the only thing he could cling to – he concentrated on it, sensed the swell and ebb in its intensity. But even that was fading now.

He had to hold on . . . but he was letting go.

1

DORSETSHIRE, 617 – RAJTHANAN NEW CALENDAR (1852 – EUROPEAN NATIVE CALENDAR)

Jack Casey crept through the trees near the front of the house. It was after nine at night, but it was summer and the sky still suspended trails of blue within the darkness. He could see the lantern beside the front gate and make out the new guard, Edwin, leaning against the wall beside it, picking at something in the sole of his boot.

Jack stepped on a twig, which gave a loud snap. He froze.

Damn. He was out of practice.

The trees rustled in the slight breeze. Faintly, he could hear people talking back in the house, the tinkle of glasses and the rattle of plates being cleared away.

Edwin didn’t react at all.

Jack shook his head, then advanced, hardly making a sound now – he hadn’t completely lost his touch.

Edwin was still oblivious to the approaching danger. Jack stood poised in the darkness, just a few feet away from the lad, then stepped out. ‘Bang – you’re dead.’

Edwin jumped and fell back against the wall. ‘Christ! You nutter.’

‘If I was an intruder, you’d be lying there dead and I’d be on my way to the house.’

Edwin sniffed. ‘But you’re not an intruder. There are no intruders. Nothing ever happens around here.’

‘And that’s the danger. It’s quiet. You get lazy. Then – pow – you’re dead.’

‘You’re mad, you are. We’re in the middle of the country. There’s no one around.’

Jack smiled darkly, his weather-beaten features creasing more deeply. He had a triangular face that seemed to emphasise his eyes and his craggy brow. His eyes were narrow and pale, the irises almost white in the dim light. His long hair was tied back in a ponytail, and he wore a brown, knee-length tunic that was spotlessly clean.

‘That’s what you think.’ He looked about as if there were enemies in the trees. ‘There are thieves and vagrants. You get bandits in the hills.’

‘Bandits? How often have they tried to get in here, then?’

‘They know we’re here watching. If they come, they see us and go on to the next farm. But if they see us dozing, that’s when they’ll strike.’

‘If you say so.’

Jack shook his head. He was too soft on the boy. That sarcastic attitude would have been beaten out of him within one day in the army.

‘Did you hear about the Ghost?’ Edwin asked. ‘Struck again last night. Knocked out the sattva link to Bristol.’

‘That so.’

‘They can’t stop him. He’s there one minute, gone the next. I heard he’s a sorcerer.’

Jack snorted. ‘Don’t you believe everything you hear down the market. The Rajthanans are a lot stronger than you

think.’

Edwin looked sideways at Jack, then spoke more softly. ‘Word is, the rebels will win.’

‘Watch your mouth, lad.’ Jack glanced over his shoulder.

‘The master hears you talking like that, he’ll fire you. If you’re lucky.’

‘I’m not scared of him.’

‘Well, you should be. You’re talking treason. You’ll get yourself reported to the sheriffs.’

Edwin looked down and scuffed the ground with his boot. ‘It’s still true.’

‘The Rajthanans rule all of Europe, and a lot of other places besides. You really think a few mutineers in England can beat them?’

‘They’ve got London now, and the whole south-east.’

‘Once the Rajthanans have built up their army they’ll smash those mutineers to pieces.’

Edwin muttered something inaudible.

‘Listen, lad. I’ll give you some advice. Forget about this Ghost or the mutiny or whatever other rubbish is filling your head. There’s an order to things and there’s no point in fighting against it. Some people rule, others follow. That’s the way of it. The Rajthanans rule here and we follow. Now, you look sharp and keep your eyes peeled. And don’t you dare fall asleep.’

Edwin bowed with his hands pressed together, as if Jack were an army officer. ‘Namaste, great master.’

Jack rolled his eyes and walked off into the darkness to continue his evening rounds. Edwin had no idea what he was talking about. The rebels might have won a few battles, but that was only because there were hardly any foreign troops in England – there had never needed to be. Now the Rajthanans were bringing in French and Andalusian regiments, and even soldiers from Rajthana itself. Once they’d built up their army in the south-west they would crush the rebellion. It was as simple as that.

He followed the stone wall for a few feet, went through a gap in the trees and came out on the front lawn. Before him stood the house. It was two storeys high, more than a hundred feet wide, and built in the style of a Rajthanan palace with miniature spires and domed towers. In places, lacy detail in bas-relief lined the rust-coloured walls. The leaded-light windows glowed and cast a series of bright blocks across the grass.

Through an arched window, he could see the dining room, where silver thalis and bowls glinted on the table. Dinner had just finished and Shri and Shrimati Goyanor had risen and were gesturing for their three guests to join them in the drawing room. Shri Goyanor – a short, plump man – wore his usual beige tunic, while his wife stood tall and elegant in an emerald sari. The children had probably already been sent to bed. Servants in white were busily clearing the table.

Shri Goyanor was obviously in a good mood – he beamed and rubbed his stomach as he spoke. He was a good-hearted man. He could be sullen, but then so could anyone. The main thing was that he always kept his word, and Jack valued that. It was like in the army. You trusted your officers because they treated you fairly, and in return you would lay down your life for them if they asked you to.

Jack went on around the side of the house and past the line of palm trees that Shrimati Goyanor insisted on trying to grow. He met Tom, the nightwatchman, coming the other way.

‘Evening,’ Jack said.

Tom raised his lantern and nodded back. He didn’t speak much and Jack approved of this. Tom was a reliable man, who’d been at the house for eight years – almost as long as Jack himself. During that time Jack had never caught him shirking or sleeping on the job, although perhaps he did like a drink a little too much.

‘Keep an eye on Edwin,’ Jack said. ‘Don’t let him leave that gate.’

‘Aye, I’ll watch him.’

Jack continued to the back of the house, where only the light from the pantry trickled across the lawn. Ahead of him, the four acres of the gardens were almost pitch black. Off to the right, behind a row of bushes, stood the wall of the servants’ compound.

‘Jack.’

Sarah, the head cook, appeared from the pantry and slipped across the grass towards him.

He cursed under his breath. He’d been avoiding her. He’d slept with her a few nights ago, but that had been a mistake. Now she seemed to think there was something between them.

She stepped out of the shadows and looked up at him. She was pretty, with brown hair that fell in thick locks past her shoulders.

‘Haven’t seen you around much,’ she said.

‘Been busy.’

‘Big night tonight. The mistress’s been in a right state.’ She waggled her head and imitated Shrimati Goyanor’s thick Indian accent. ‘I told you never to use garlic and onions when we have government officials to dinner.’

Jack smiled slightly.

‘I’m dead tired now, though,’ she said. ‘Got another blessing in the morning too, first thing.’

Jack knew that all cooks had to be blessed regularly if they were to prepare food for the Rajthanans. The Rajthanans had a lot of strange ideas about food and drink. It was something to do with their system of caste, which they called jati. The higher jatis wouldn’t take food from the lower jatis, and no one would take it from Europeans unless they were blessed. Jack had actually seen a dying officer in the field refuse water from a native soldier to avoid being polluted.

‘If you have an early start I’d better let you get on,’ Jack said quickly, turning to leave. Maybe he could get away before things got difficult.

‘Jack.’

He stopped and turned back.

Her face was serious now. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Look, I’m sorry if I gave you the wrong idea—’

‘I see.’ A glint of moisture appeared in one of her eyes. She looked off into the dark gardens. ‘Like that, is it?’

‘You know the rules. Servants can’t be couples. We’d get fired.’

‘No one would find out.’

‘We can’t risk it. Anyway, you could do better than me. Get yourself a good man. Get married.’

He meant it. He wasn’t well, not since . . . his accident. Sarah didn’t know about his injury and he didn’t want to burden her with it. She should have a strong man who could take care of her . . . But there was more to it than that. If he were honest, the memory of his wife, Katelin, still held him back.

‘Have it your way, then,’ Sarah said, with an edge of bitterness to her voice. She turned to leave.

‘Wait.’

She looked back.

What could he say? ‘It’s for the best.’

She huffed, spun away again and marched back to the house, her long dress swishing about her.

Jack scratched the back of his neck. That had gone about as well as could be expected. At least it was over now. Part of him wished he could just give in and be with Sarah. She was a good woman. But it would never work.

He pressed on into the darkened grounds, crossed the small stone bridge over the brook and continued into the formal garden. Oblong-shaped, ornamental trees stood in rows beside ponds that reflected the moon. Lines of white orchids and lilies swayed in the breeze. He smelt the cool fragrance of flowers and moss. The wooden gazebo, half buried by vines, brooded in the centre.

Beyond the garden was a series of hedges and then the orchard. He walked between the apple and pear trees, smelling the sweetness of the growing fruit.

About halfway through, the hairs suddenly stood up on the back of his neck and his skin rippled. The air seemed to tremble with a strange energy. He’d been expecting this.

He stopped and sniffed. A faint, but familiar, scent encircled him. It was like a mixture of sandalwood, musk, saffron and rosewater. Distinctive, yet impossible to describe.

Sattva.

A powerful stream coursed through the grounds here, and he sensed it every time he walked through. He was sure no one else in the house knew about it. Only he had the sensitivity and training to detect it.

He took a deep breath. That smell reminded him of the past, back when he’d still been able to use his power.

A movement off to the left disturbed him. What was that?

He crouched, peered into the gloom, listened intently, searching the surroundings for signs. Tracking came to him instinctively – he’d learnt the skill from his father from the moment he could walk.

He noticed the movement again – a quick swish near to the ground. He sneaked forward and paused, partially concealed by a tree trunk. Despite the warning he’d given Edwin, the only intruder during all his years as head guard had been a vagrant boy stealing fruit. He waited for several minutes and then a red-brown streak shot between the trees and disappeared – a fox. He gave a small chuckle. He’d thought as much, but it was always best to be cautious. The old army training, the old reflexes, would never leave him.

He slunk to the end of the orchard – leaving the sattva stream – and reached the stone wall that marked the perimeter of the property. Beyond the wall lay miles of fields belonging to Shri Goyanor – the nearest neighbours were five miles away.

He walked beside the wall until he reached the iron gate that was the only back exit to the property. He checked that the bolts were secure and then, satisfied that everything was in order, set off back towards the house.

As he crossed the bridge, he started to feel out of breath.

He stopped on the other side and leant against a willow tree. He tried to catch his breath, but his chest felt tight and sweat formed on his forehead. This had happened several times recently. What was wrong with him? Was his injury getting worse?

He shut his eyes, and after a minute his breathing eased. That was better. He opened his eyes again and went to move on.

Then he felt a thump in his chest, as though someone had kicked him. His ears rang and white spots spun before his eyes. He fell against the tree and sat there, hunched. He was choking. He tried to call for help, but he was too weak even to do that. Blackness passed over him and he fought to stay conscious.

‘Jack!’

He opened his eyes. Sarah was crouching over him with a lantern in her hand.

He blinked. He felt better – he could breathe again and the pain in his chest had gone.

Sarah crossed herself. ‘Thank the Lord. You had me worried there.’

He sat up against the tree. ‘What happened?’

‘You tell me. I heard this choking sound and I came down here and found you out cold.’

‘Ah. Think I fainted. Haven’t been feeling too well lately.’

She frowned. ‘You should see a doctor.’

‘No need for that.’ He struggled to his feet. ‘Just a touch of the flu.’

‘Flu, my foot! At the mission hospital—’

‘I said, there’s no need.’

Her eyes flickered. ‘You’re bloody impossible.’

‘Don’t make a scene.’

‘Don’t make a scene?’ She raised her voice and turned as if calling out to the house. ‘Why, you worried the master will find out about us?’

‘Sarah—’

‘Think you’ll lose your job?’

Jack winced as his chest tightened again and his breathing became laboured.

She paused for a second. ‘Jesus. You look terrible.’

He waved her away. ‘I’ll come right in a moment.’

‘You’d better get back to your room.’

He was too weak at that moment to disagree, and he let her walk with him to the compound and past the small white-walled huts of the other servants. By the time they reached his hut he was feeling a little stronger.

She followed him into his room, despite his protest. He lit a lantern, revealing his plain cubicle. A sleeping mat lay on the floor, a few blankets folded neatly at the end. His spare clothes, also neatly folded, sat on top of a crate in a corner. The stone floor had been carefully swept and washed.

‘Why don’t you lie down?’ she said.

‘I will . . . in a minute.’

‘Here, let me get this.’ She bent to move a carved wooden box that was sitting in the middle of the sleeping mat.

‘No.’ He slammed his hand over the box. Then he saw the surprise on her face and his voice softened. ‘It’s just something pers

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...