1

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

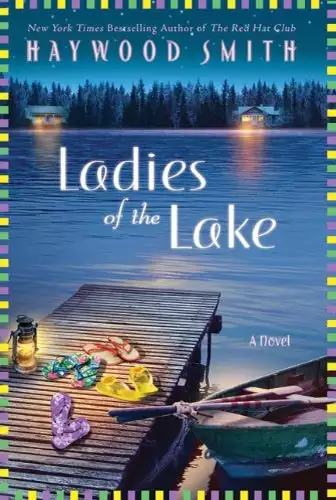

Ladies of the Lake

Haywood Smith

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Close