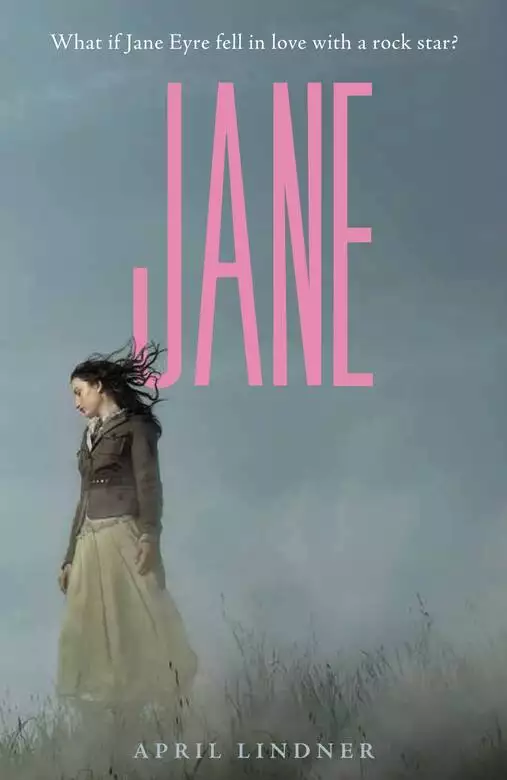

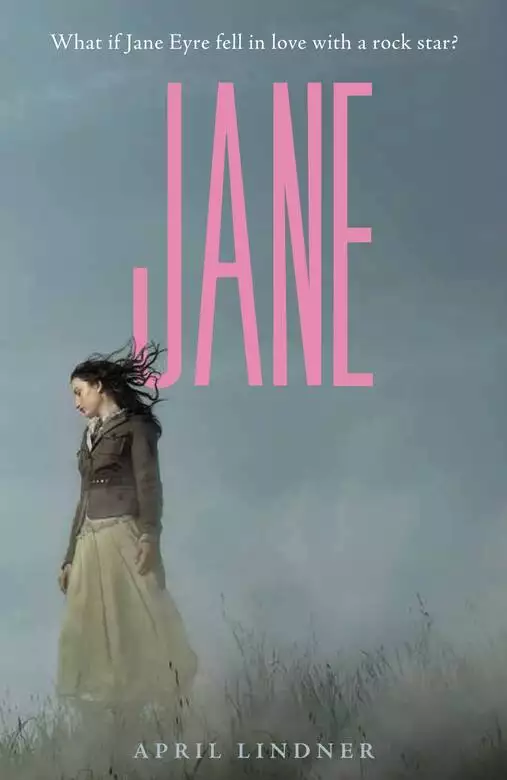

Jane

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Forced to drop out of an esteemed East Coast college after the sudden death of her parents, Jane Moore takes a nanny job at Thornfield Park, the estate of Nico Rathburn, a world-famous rock star on the brink of a huge comeback. Practical and independent, Jane reluctantly becomes entranced by her magnetic and brooding employer and finds herself in the midst of a forbidden romance. But there's a mystery at Thornfield, and Jane's much-envied relationship with Nico is soon tested by an agonizing secret from his past. Torn between her feelings for Nico and his fateful secret, Jane must decide: Does being true to herself mean giving up on true love? An irresistible romance interwoven with a darkly engrossing mystery, this contemporary retelling of the beloved classic Jane Eyre promises to enchant a new generation of readers.

Release date: October 11, 2010

Publisher: Poppy

Print pages: 358

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Jane

April Lindner

nearest the exit, where, feeling like an impostor in my gray herringbone suit from Goodwill, I could watch the competition

come and go. I’d had some trouble walking up the steps from the subway in my low pumps and narrow skirt. The new shoes chafed

my heels, and I had to keep reminding myself to take small steps so as not to rip the skirt’s satin lining. I dressed carefully

that morning, pulling my hair away from my face with a large silver barrette, determined to look the part of a nanny—or

how I imagined a nanny should look—tidy, responsible, wise.

But I had gotten it wrong. The other applicants seemed to be college girls like me. One had situated herself in the middle

of the taupe sofa and was calmly reading InStyle magazine; she wore faded jeans and a cardigan, her red hair tousled. Another, in a full skirt and flat shoes I coveted, listened to her iPod,

swaying almost imperceptibly in time to the music. But maybe they weren’t feeling as desperate as I was, acid churning in

my stomach, pulse fluttering in my throat.

In my lap rested a leather portfolio containing my woefully brief résumé, my nanny-training certificate, a copy of my transcript,

and nothing else. The portfolio had been a Christmas gift from my parents just a few short months ago. It was one of the last

gifts they had given me before the accident. But as I waited, I couldn’t let myself dwell on how my mother had handed me the

box wrapped in gold paper and, her eyes not meeting mine, how she had apologized for not knowing what sort of present I would

like. I felt a pang of remorse; her tone implied the failing was mine. I’d heard it before: I was too reserved, too opaque;

my interests weren’t normal for a girl my age. Still, my mother had let me give her a thank-you kiss on the cheek. She appeared

relieved when I told her the portfolio was just what I would need when I finished school and went out into the world looking

for a job. Of course, neither of us realized then how soon that need would arise.

“Jane Moore?”

I looked up. A thin woman with an asymmetrical black bob stood in the doorway. I jumped to my feet. Too eager, I chided myself. Try not to look so desperate. The woman quickly sized me up. I could see it in her sharp eyes and closed-mouth smile: I was dressed like a parody of a

nanny, too fussily, all wrong. She introduced herself as Julie Draper, shook my hand, turned briskly, and strode through the

door and down a long hallway. I hurried after her.

The narrow office held too many chairs to choose from; was this a test? I took the one closest to her desk, careful to cross

my legs at the ankles and not to slouch. I handed my certificate and my résumé—proofread ten times and letter perfect—across her enormous mahogany desk. Through purple-rimmed reading glasses, she scanned it in silence. Just when I thought I

had better say something, anything, she looked up.

“You would be a more attractive candidate if you had a degree. Why are you dropping out?”

“Financial need.” Though I had expected this question and rehearsed my reply, my voice caught in my throat. On the subway

ride downtown, I had considered telling the whole story—how my parents had died four months ago, black ice, my father’s

Saab flipping over a guardrail. How they hadn’t had much in the way of life insurance, and the stocks they left me in their

will had turned out to be almost worthless. How the house had been left to my brother, and how the minute he sold it he disappeared,

leaving no forwarding address, no phone number. How the spring semester that was coming to a close would have to be my last.

How I’d been too depressed to plan for my future until it dawned on me that the dorms were about to close and I’d be homeless

in less than a week. How the only place I had left to go would be my sister’s condo in Manhattan, and how very displeased

she would be to see me on her doorstep—almost as displeased as I would be to find myself there. But I couldn’t trust my

voice not to quaver, so I stayed silent.

Julie Draper looked at me awhile, as if waiting for more. Then she glanced back down at her desk. “Your grades are strong,”

she said.

I nodded. “If you need more information, faculty reports for each of my classes are stapled to the back of my résumé.” My

voice sounded clipped and efficient and false.

She rifled through the pages. “I see most of your classes were in art and French literature.” I waited for her to point out

how hugely impractical my choices had been, but she surprised me. “That kind of training could be very attractive in a nanny.

Many of our clients want caregivers who can offer cultural enrichment to their charges. A knowledge of French could be very

appealing.” A pause. “And you’ve taken a couple of courses in child development. That’s a plus.”

“I’ve been babysitting since I was twelve. And I took care of one-year-old twins last summer.” Too bad I’d had to spend all

my savings on textbooks and art supplies for the spring semester. “My references will tell you how reliable I am and how much

their children like me. I’m strict but kind.” I paused to inhale; apparently I’d been forgetting to breathe.

Something changed in her voice. “Tell me: how do you feel about music?”

“I took violin lessons in middle school,” I answered. “I don’t really remember how to play.”

She waved one hand as if I’d written my answer on a blackboard and she was wiping it away. “Popular music. How do you feel

about it?”

The question struck me as odd. “Well,” I said, stalling a moment. “I don’t mind it, but I don’t listen to it much.” Would

this be a strike against me? “I tend to like classical music. Baroque. Romantic. But not the modern atonal kind.”

“And celebrities?” She leaned in over the desk. “Do you read gossip magazines? People? Us, Star, the National Enquirer? Do you watch Entertainment Tonight?”

The hoped-for answer to this question began to dawn on me. Fortunately, it was the truth. “I don’t care much about celebrities.”

“How do you react when you see them on the street?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I might as well be honest. “I’ve never seen one on the street.” I sat up a little straighter. “I believe

I would leave them alone.”

She pursed her lips and narrowed her eyes. A moment passed. Then she smiled for the first time, a wide smile that revealed

slightly overlapping bottom teeth. “You just might be perfect.”

The morning after the interview, my cell phone rang. I was walking back to the dorm from the bookstore where I’d turned in

my textbooks for a not-very-satisfactory amount of cash. I paused on the pathway and let the other students flow around me.

On the line was Julie Draper, sounding slightly breathless, much younger, and less formidable than she had in person. “Jane,

I’m so glad to catch you. I have great news, a position to offer you.”

My heart thumped so loudly I worried she might be able to hear it through the phone. “That’s wonderful,” was all I dared say.

“More wonderful than you know,” she told me. “This is a plum position. By all rights it should go to a more experienced child-care

provider, but until you came along, I hadn’t been able to find a candidate I could trust to have the right”—her voice trailed

off—“the right attitude.”

I cast around for my job-interview voice, the one that had apparently served me so well yesterday. Though she couldn’t see

me, I threw back my shoulders and raised my chin. “I look forward to hearing more. Where will I be working?”

Julie Draper laughed in a surprisingly musical tone. “This will sound bizarre, but I can’t give you any more details over

the phone. How soon can you be at my office?”

When I arrived at Discriminating Nannies, the first thing Julie Draper did was offer me coffee in a slightly chipped mug.

Then she swore me to secrecy.

“You can’t tell anyone the details of this position,” she warned. “Not your friends, not your family.”

“I promise.” It would be an easy vow to keep. Who would I tell? My best friend from Sarah Lawrence had transferred to a school

in her home state, Iowa; on top of classes, she’d been working extra shifts to save up for a semester abroad in Italy, and

we hadn’t spoken in months. And after the accident I hadn’t had the heart for socializing. I knew I would drag down any party

I went to, so I spent most of my time in the studio, priming canvas after canvas, trying to settle on something to paint.

Every idea I came up with—the stand of trees outside the wide window, an abandoned bird’s nest I’d found on a walk, my own

pale face in the mirror—made me tired, my arms too heavy to lift even a paintbrush. More nights than one, I’d slept on the

sagging, paint-flecked studio couch, unable to face the five-minute walk back to the dorm. My parents had never quite understood

me, and Mom had never made any secret of the fact that my conception had been a less-than-welcome surprise. You might think

those things would make me slightly less miserable about losing my parents, but in some ways it made the loss even worse. Not only had they never shown me the kind of attention and appreciation they’d given my

brother and sister, now it was official: they never would.

“Your future employer is, well, let’s just say, he’s of interest to the media.” Was that a dimple in Julie Draper’s cheek?

“A celebrity. It’s crucial that you not do anything to call attention to him. Anything that goes on in his house, no matter

how big or small, must not be discussed with outsiders.” The dimple disappeared. “There will be a confidentiality agreement

to sign. You are free to run it by a lawyer.”

A lawyer? A confidentiality agreement? It did me little good to wonder what exactly I was getting myself into; at this point,

I was already in it up to my ankles. “That won’t be necessary,” I said, trying to sound calm. “I’m happy to sign.”

“To be absolutely honest, you were chosen because I have an instinct about you,” Julie told me. “You seem trustworthy.”

I nodded as solemnly as I could. But then I couldn’t help myself; I blurted out, “But what sort of person is my employer?”

“Jane,” she said, dimple returning, “surely you’ve heard of Nico Rathburn?”

She didn’t say “surely even you have heard of Nico Rathburn,” but the “even you” was in her voice. And it was true, even I had heard of Nico Rathburn. I

probably knew all the words to his hit song “Wrong Way Down a One-Way Street.” It was one of those songs you heard everywhere

you went—at the mall, in the grocery store, blaring from the radios in other people’s cars. I could still recall Rathburn’s

cool dark stare in a poster tacked up on the wall above my brother’s bed, his denim-clad form posed in front of a brick wall, a flame-red electric guitar brandished in his hands. Mark had gone to one of his concerts. I was little then,

maybe in elementary school, certainly too young to stay home alone, so my mom dragged me along on the ride into the city,

Mark and his best friend chortling in the backseat, playing with the Bic lighters they would ignite to demand an encore. I

remember being afraid they would set the upholstery on fire. And I’d been brought along on the ride to pick them up from the

Spectrum too. I remember the strange and pungent smell that clung to the oversized black concert T-shirts they wore over their

usual clothes, and the lights of the city, a thrilling expanse of electricity and skyscrapers glimpsed from the highway overpass

that hastened us back to the suburbs.

But even if Mark hadn’t been a fan, I would have heard of Nico Rathburn. For as long as I could remember, he’d been one of

those celebrities whose name conjured up instant associations, most of them having more to do with his dramatic personal life

than his music. I vaguely recalled something about his being busted for possession of cocaine, something else about a car

crash and a string of high-profile girlfriends. Then there was the on-again, off-again marriage to a model whose name I couldn’t

remember. Hadn’t they both been junkies? Suddenly chilled, I rubbed my arms for warmth. How badly did I need this job? I thought

of my dwindling savings account, of the few belongings I hadn’t carted to Goodwill that were crammed into a couple of suitcases

on the floor of my dorm room.

“Sure, he’s been out of the papers for a few years,” Julie continued, “and you’d think he wasn’t such a hot commodity anymore.

But the tabloids are like sharks, always circling, hungry for blood. He needs his employees to be absolutely discreet.”

“Um,” I stammered. “He has children?”

“A girl, five years old, named Madeline. It was in the news, but you don’t remember, I suppose.” Julie’s voice turned impatient,

despite the fact that she hired me precisely because I wouldn’t care about such things, much less remember them. “Madeline’s

mother was a pop star in France; she cut a solo album on a U.S. record label a few years back. That was the high point of

her career. Maybe you’ve heard of her? Celine?”

The name was familiar. “What happened to her? The mother, I mean. Does she have shared custody?”

“The details shouldn’t concern you.” Julie was back to the brusque, professional version of herself. “Not that they wouldn’t

be hard to find if you went looking for them. But I’d advise you not to buy into every overblown story you read in the tabloids.

That business with his wife, with Celine, the drug use.… He’s been sober for a while now. That’s all you really need to know.”

“Oh,” I said. “I’m glad to hear it.” My voice didn’t have much conviction in it.

“Listen, Jane.” She looked pointedly in my eyes. “Nico Rathburn is a devoted father. That bad-boy stuff is old news. Besides”—she paused for emphasis—“the pay is excellent. You’ll be living in a mansion in Connecticut. And you’ll get… you’ll get

proximity to one of the gods of rock-and-roll music. You do know how many nannies would kill for this position, right?” She rifled

through a folder and drew out a document on legal-size paper. “You’re a lucky, lucky girl.”

Despite Julie’s advice, I spent my last evening on campus in the library computer lab, reading everything I could find about

Nico Rathburn. It wasn’t so much that I cared about the story of his love life, criminal record, and meteoric rise to stardom;

if anything, the details made my stomach twist in knots. But I believe in being prepared.

The lab was air-conditioned to an Antarctic chill, and I thought longingly of the lone sweater still hanging in my closet.

Classes were over, and apart from me the lab was empty. Every now and then I’d hear laughter and shouts as groups of students

passed the window on their way to some celebration of the semester’s end.

It didn’t take me long to find an astonishing amount of information about my new employer, little of it reassuring. Rathburn’s

early press was mostly positive, fawningly so. The Rathburn Band had weathered middling success for a while, playing clubs up and down the East Coast until their third album bowled the critics

over and became a breakaway hit. I could remember that album blaring from behind the locked door of Mark’s room every afternoon

for months. One song in particular, “Wrong Way Down a One-Way Street,” played irritatingly in my brain as I read record reviews

and Wikipedia articles, my eyes glazing over. Nicholas Rathburn’s Wichita boyhood had been unremarkable. An indifferent student,

he disappointed his parents by running off to Brooklyn and starting up a band instead of going to Kansas State. Rathburn and

his bandmates had shot abruptly from obscurity to fame—a Rolling Stone cover, multiple platinum records, international tours.

At a fan site I discovered photos of Nico Rathburn at the peak of his celebrity, in leather pants and mirrored sunglasses,

dragging a blonde, miniskirted model past the paparazzi. There were many variations on that theme; the sunglasses remained

the same, but the blonde girlfriends were interchangeable. At his official website, I found tons of in-concert photos, Rathburn

grimacing in concentration as he played guitar or throttling the mike as he sang, head thrown back. Then there were the stagey

professional shots—his dark hair fluffed up, his smoke-gray eyes fixed on the camera as though he were looking past it to

the person who would be viewing the photo years later.

In his twenties, he cultivated a quieter look, exchanging the skin-tight leather pants and muscle shirts for black denim and

plaid flannel. Despite his new low-key persona, he dated debutantes and actresses, and owned a penthouse apartment in Lower

Manhattan, a villa on the Ligurian coast, and a mansion in the Hollywood hills. Many of the stories were about his wedding

to Bibi Oliviera, a model who had just made her first appearance in Vogue. Unlike his other girlfriends, she was dark haired with sun-kissed skin, a big, engaging smile, and leaf-green eyes. They’d

met in her native Brazil when she starred as the love interest in one of his music videos. On their first weekend together

they’d gone out and gotten matching tattoos—a coiled green serpent with a heart clenched in its bared fangs on his left

forearm, and its twin on her right one. A few days later, they flew to New York City and got married at city hall.

From the wedding onward, the news stories piled up, too many for me to read. I skimmed several. There were drug busts, minor

car crashes, violent public fights and recriminations. In one strange episode, a male neighbor discovered Bibi shivering in

her underwear, mascara dripping down her face, apparently disoriented, cowering on his front porch. “Nico locked me out,”

she had told the policeman called to the scene. “It wasn’t really him—the devil was looking out at me from his eyes. I would

have slit his throat if I’d had a knife.” Blurry photos documented this story; I lingered over them awhile. But for the snake

tattoo, this version of Bibi looked nothing like her earlier, glamorous self. Skinny as a famine victim, black hair matted,

she slouched between a pair of cops, her wide green eyes broadcasting panic. Someone had thought to throw a blanket over her

shoulders at least; just looking at her made me feel cold and anxious. Still, I forced myself to read on. Bibi’s breakdown

had led to a stint in celebrity rehab. Released after a few months, she seemed to be on track to recovery. She’d gone back

to work and was even featured on the cover of Femme, but there didn’t seem to be much news about her after that.

A loud bang just outside the computer lab window startled me back into the present. It was only fireworks; more of them crackled

and fizzed out on the lawn to laughter and cheering. Still, the noise had set my heart pounding, and a strong surge of foreboding

seized me. In what kind of universe did people wander through their neighborhoods in lacy black panties, too stoned to care

what other people thought of them, squandering their tremendous good fortune on cocaine and heroin? No universe I cared to

live in. Still, I needed to understand what I was getting myself into. I took a few deep breaths, steadied my hands, and kept

clicking.

Not long after Bibi’s release, the couple had separated. Nico Rathburn’s next album, a downbeat collection of songs about

disillusionment and romantic dysfunction, was reviewed favorably—“Grown-up songs for sophisticated listeners,” the New York Times had called it—but didn’t get much airplay. Maybe the songs were too somber, or people were simply ready for the next big

thing. He fired his band, telling the press he was ready to shift gears. I couldn’t find many articles from the months right

after that, but then Rathburn began dating a French pop star so famous in her native country that she was known simply as

Celine. The sheer volume of magazine articles gushing about the happy couple made my eyes start to glaze over. Fortunately,

there wasn’t much more of the Nico Rathburn saga to get through. After their very public breakup, he sued her for custody

of their daughter, Madeline. He won, bought an estate in Connecticut, and went into seclusion.

A recent People profile brought the story up to date. Rathburn had reunited the band to record another album—his “big comeback,” the article

called it. His story was a bit sad, really, or so it seemed to me. All that success hadn’t kept him from having to woo the

public all over again.

The computer lab closed at midnight. I made my way across campus, sticking to the well-lit paths, and slipped into the dorm

and past the downstairs lounge, where I could hear laughter and music. I felt exhausted and sorry I had stayed up so late

poring over celebrity gossip like an obsessed fan. I had to catch an early train in the morning. But after I brushed my teeth,

pulled on my nightgown, and climbed into bed, my eyes refused to shut. I stared at the thin bands of street light playing

around the edges of my window shade and tried to silence the voices in my head.

Of all the jobs I could have been chosen for, this one seemed a peculiarly bad fit. Unlike most people, I wasn’t drawn to

glamour and excitement; quite the opposite. I just wanted regular work and a steady paycheck. I’d seen what striving after

fame and admiration could do to a person. My older sister, Jenna, had acted as a child. She was featured in a few local commercials

and had some roles in community theater. After college she went off to New York City to pursue what she loftily referred to

as “my career,” but after some disappointments—a lot of rejection and then a sizable role in a TV pilot that didn’t get picked up—she

had gotten engaged to an investment banker and moved into his condo in Tribeca. Jenna and I hadn’t spoken since our parents’

funeral, but at the lunch afterward, she kept leaving the restaurant to smoke, winced almost imperceptibly whenever her fiancé

spoke, and mentioned—twice—that she was just biding her time until the right opportunity came along. Jenna would have jumped at the

chance I was being given to live in a mansion among the rich and famous. She’d be making plans to seduce and marry one of

the rock star’s wealthy friends, if not the man himself. If she could see me now, panicking in the dark, she’d roll her eyes

and call me anal-retentive and prissy.

The pay is good, I consoled myself. In fact, the amount Julie Draper had quoted me was much better than I’d hoped for. I’d be able to live

very cheaply and save almost all of my earnings. If I could just last a year, I might even be able to go back to school, although

probably not to Sarah Lawrence. Still, I would be able to earn my degree. My time in the alternate universe of coke-snorting

rock stars and their strung-out wives and girlfriends would be brief.

In the meantime, I’d get by, doing exactly what I’d solemnly promised Julie Draper I would do before I signed a pile of legal

documents relinquishing the right to sue her agency or Nico Rathburn if anything should go wrong: I would behave with absolute

professionalism no matter what debauchery went on around me. I would stay as anonymous as possible, do my job, and blend in

with the furniture. That should be easy. I’d never been the kind of person people notice.

The ride to Penn Station was packed with commuters; I got more than a few glares from men and women stuck behind me as I struggled

to hoist my suitcases into the overhead rack. The outbound train to Connecticut was emptier; I chose a window seat so I could get a good look at the countryside where I would be living. Unlike my classmates, many of whom had spent semesters

abroad and backpacked across Europe in the summer, I had never traveled much. My sister’s many auditions and occasional acting

jobs had kept us close to our home just outside Philadelphia most summers, and my parents had never cared for traveling anyway.

“We have everything we need right here,” my father would say. “We’re two hours from New York, two hours from Baltimore, two

hours from the mountains, two hours from the shore. We’re right in the middle of everything.” We never went to any of those

places, though.

Of course, there were school field trips to the zoo and to the natural history museum and out to Amish country. And my sister’s

auditions often brought us into Center City Philadelphia after school. My mother would drive us in her Volvo, her hands tightly

gripping the steering wheel. Once at our destination she would herd us nervously through the parking lot, so quickly that

I never got a chance to look around. In the elevator, Jenna would fret about the wrinkles in her dress from sitting so long

in the car, while Mom would check Jenna’s makeup and smooth down any flyaways in her curly auburn hair.

After Jenna and Mom were called into the office, I would read in the waiting room, losing myself in that day’s book. Jenna’s

appointments usually took a few minutes or half an hour, but whenever she came out was too soon. Sometimes she would be snippy,

dissatisfied with her dress or hair. “I’ll never get jobs if I don’t have the right clothes,” she’d complain. Other times,

she’d be happy. “I nailed it, Mom, didn’t I? Don’t you think they liked me?” she’d say, and our mother would spend the whole ride home reassuring Jenna of her beauty, poise, and talent.

“Jenna got the looks and the personality,” I once heard Mom whisper to Dad over a six o’clock cocktail; she must have thought

I was in the back room watching cartoons instead of behind the couch, playing spy. “Nature doesn’t play fair.”

“Jane’s good-looking enough,” Dad had responded in a voice meant to be consoling. “She’s shy, but she’ll come out of her shell.

She’ll learn to compensate.”

“You think so?” The ice clinked and sizzled in Mom’s glass. “She’s so intense and serious. Not a very appealing personality.

You really think she’ll grow out of it?”

I can’t remember my father’s reply or whether or not they caught me eavesdropping, but I do remember looking up compensate in the dictionary and being disappointed by the definition. I had hoped it would mean something like “blossom” or “grow up

to surprise us with her poise and beauty.” I remember wishing on first stars and stray eyelashes for my wispy brown hair to

grow thick and shiny so that Mom might decide I was pretty after all.

While the train halted in the tunnel for a signal, I checked my reflection in the dark glass. In high school, I had taught

myself to do my hair so that it was at least neat—straight, parted down the middle, held in place by a French braid. Like

Jenna, I was thin; how often had my suitemates marveled at my ability to eat heartily without gaining weight? Unlike Jenna,

I’d never grown much in the way of breasts. She got the long legs too and stood a whole head above me. My nose was straight,

my teeth okay, my mouth decently shaped but a bit thin in the lips. I’d inherited my father’s green eyes, not the long-lashed, ice-blue ones nature had given my mother and sister. In . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...