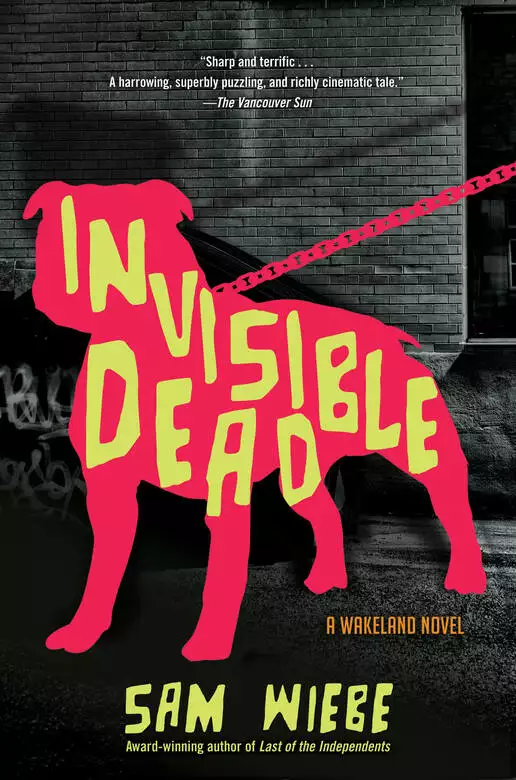

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A gritty private-eye series begins on the streets of Vancouver, featuring an ex-cop with a moral compass stubbornly jammed at true north.

When PI Dave Wakeland is hired by a terminally ill woman to discover the whereabouts of her adopted child, who disappeared as an adult more than a decade earlier, it seems like just another in a string of poor career decisions.

Wakeland is a talented private investigator with next to zero business sense. And even though he finds himself with a fancy new office and a corporate-minded partner, he continues to be drawn to cases that are usually impossible to solve and frequently don’t pay.

But it turns out this case is worse than usual, even by his standards. An anonymous tip leads Wakeland to an imprisoned serial killer who steers him toward Vancouver’s terrifying criminal underworld. With nothing to protect him but his wit and his empathy for the downtrodden and disenfranchised, Wakeland is on the case.

Release date: May 2, 2017

Publisher: Quercus

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Invisible Dead

Sam Wiebe

I generally don’t like serial killers—don’t find them interesting—though I could name a couple exceptions. Nichulls wouldn’t be one. But a client had received a tip-off that Nichulls knew something about her daughter’s disappearance, so I made the drive to Agassiz to see if it was true.

The Kent Institution is two hours east of Vancouver, past sprawling townships that seem intent on chewing through their farmland, regurgitating strip malls and noose-shaped cul-de-sacs of tract housing. Kent is federal and maximum security, a large brown bunker flanked by caged-in exercise yards. Next door is the medium-security Mountain lockup. Corrections is the town’s chief industry.

A tall guard with a scar on her cheek walked me through the checkpoints, down the long hallway, concrete walls painted white and green. A conference room had been arranged. Inside was another guard, stone-faced, and a thin man in an expensive pinstripe suit that hadn’t been taken in. His two-button vest flopped around his midsection. He rose to shake my hand.

“Tim Kwan. Nice to meet you, Mr. Wakeland. I’m his counsel. For today, anyway.” We shook and Kwan sat back down, smoothing out trousers that hadn’t been pressed. “He gets a lot of requests for his time.”

“I won’t take up much of it,” I said.

We waited while the guards fetched Nichulls. Kwan sketched runic-looking figures in the margins of his day planner. I studied the two photos that I’d brought with me. The first was of a young blonde seated in front of an antique bookcase, her posture square and erect, one elbow propped on a desk next to a globe. It was a yearbook photo—I could see ripples in the backdrop on which the bookcase was printed, the shadow of the next kid in line falling across the globe.

The other photo showed a much older woman, leaning into a graffitied brick wall. Not older—aged. Rough, defiant, sexual. Eyes heavy-lidded and suspicious. Black hair, black eyeliner, overdrawn crimson mouth. A sneer levied at the camera lens.

That these were the same woman was just one of the contradictions of Chelsea Loam. Her adopted mother had provided ample details about the adolescent who’d been brought into the Kirby family. None of it explained why she’d left home. Or who she’d been before she arrived.

The door opened and Kwan tensed, snapped shut his notebook. Nichulls appeared between two guards. They sat him down and uncuffed him. Then they hovered behind his chair, each taking a shoulder, an angel and a devil in matching uniforms, attending on some poor sinner.

“Howdy,” Nichulls said to me.

I wanted to find something in Nichulls’s appearance that would justify revulsion. True, if he’d set his heart on a modeling career, he’d never suffer from scheduling conflicts. But homely as he was, whatever sickness resided in him didn’t reside in his face. His thinning white-blond hair, orange beard, colorless eyes, and overbite made him look at worst like a disreputable uncle. Like someone at home at flea markets or the track. Jail hadn’t faded his deeply tanned forearms, which suggested a liver or endocrine problem. Tattooed on his right arm was a blue crucifix.

Kwan leaned forward and introduced himself, informing Nichulls that Kwan worked for his usual lawyers. Nichulls smiled and watched amused as Kwan studied his hands, the floor, the textured cover of his notebook. Nichulls briefly looked over at me to see how funny I found the lawyer’s agitation. I stared back at him, waiting.

They conferred for a moment, discussing minor points of treatment and privilege. Minor for those on the outside, at least. Nichulls’s grievances had chiefly to do with meal selection.

“Three hots and a cot,” Nichulls said. “What I’m owed. Least get me some choice, y’know?”

“I’ll petition the warden,” Kwan said.

Nichulls’s eyes focused on me and he nodded and smiled. “Might as well get down to it,” he said. “Down to the nitty gritty titty. What’d you want to ask me?”

I held up the photos. He reached for them, pulled them toward him. I let go.

“First,” Kwan said, “let me reiterate that nothing you say to my client or he to you can in any way be interpreted as an admission of wrongdoing. If, however, said information proves valuable in locating someone, whether living or deceased, we would expect that information to be made available to various parole boards, committees, and appellate courts, preferably in the form of written affidavits or spoken testimonials from yourself or your office, to be used on my client’s behalf at his discretion. We’re clear?”

“Clear,” I said.

“Clear,” Nichulls echoed, grinning. “Clear as mud. Who’s this cutie?”

I told him her name. Nichulls examined the second photo. He had no problem marking the blond student and the gray-complexioned runaway as one and the same. I didn’t read recognition in his face. Only a casual lust.

“Looks young,” he said, tapping the corner of the yearbook photo.

“She was twenty-four when she disappeared. That was eleven years ago.”

“This girl a whore,” he said, a funny inflection on the last syllable.

“Are you asking or telling me?”

“Asking. If I ask you, I’m asking. She a whore?”

“She trafficked,” I said. “You’re familiar with the strolls. Have you ever seen her before?”

“Don’t think so,” Nichulls said. “No.”

“Then we’re done here.”

I rose and put out my hand for the photos. He kept them at arm’s reach from me, the way a bully might. The guards inched closer. Tim Kwan pushed his chair back slightly.

“Now hold on a minute, hold on here.” Nichulls gestured for me to sit. “I said I didn’t think so. Think’s not the same as certain. Gimme a minute. Eyes aren’t so good anymore.”

He squinted and stared at the photo of the young girl in her chiffon dress, posed in front of the cheap backdrop, arm near the prop globe. Him holding the picture felt obscene. I sat and waited. I don’t wait well.

“And?” I asked.

“Hold your horses.” He tapped his temple. “Gears don’t turn as fast as some people’s. ’Specially not after what I been through.”

“Either you know her or you don’t.”

“And I said I’m thinking. Takes as long as it takes. Where is it I know you from?”

“I’m a private investigator,” I said. “One or two cases have made the papers.”

“Don’t read ’em.”

“I was a cop before. Briefly. That must be where.”

“Nah.” He squinted at me, then nodded to himself. “The Astoria. You and that old man.”

I nodded, no use hiding it. Kwan looked at me, curious.

“I used to box in the basement of the Astoria Hotel,” I told the lawyer. “Sometimes after training, my father would take me upstairs for a drink.” I pointed to Nichulls. “We’d see him in the bar, time to time.”

A grin of absent-minded nostalgia played out on Nichulls’s face. He was a celebrity and loved being one. Back then, though, he’d been one more drunk, twisting quarters into the guts of a candy dispenser, grinning at my father the cop and my sweaty sixteen-year-old self. The grin took in the square-shouldered man sitting with the exhausted boy in the hotel bar and assumed the worst. The grin said: you are my tormentors and you are no better than me. The grin aimed beyond us, at the world, and still gracing the contours of his face now.

“Those were the times,” Nichulls said. “Not like now. You still fight?”

“No.”

“Why’s that? Not good enough?”

“Partly,” I said. “Once my father died I had no use for it.”

“Sorry to hear that, him dying.”

“I appreciate your sympathy. Could we get back to Chelsea Loam?”

“Never left her,” Nichulls said. “Kind of body’d she have? Tall, thin, fat, what?”

“Slight.”

“She dress like a whore? Real obvious-like, bright red lips?”

“I didn’t drive out here to give you beat-off details.”

His brow crinkled. “No call for salty language. Remember it’s you asking me for help.”

“You’re right.”

“Catch more flies with honey—your dad never tell you that?”

“If you ever saw her, or did something with her, tell me. Please. If not, tell me that.” The please was hard to get out.

Nichulls held up a pair of stubby fingers. “Hold on two secs. You’re working for who, ’zactly?”

“Her mother,” I said. “Adoptive mother. She’d like to see her daughter buried, if there’s anything to bury. And if not, then at least know what happened to her.”

Nichulls nodded. He’d put the photos down on the cheap wood coffee table. Tim Kwan spun them toward himself and stared, as if he hadn’t looked at them before. I wondered what kind of lawyer he was.

“The mother put up any kind of reward?” Nichulls asked.

“No.”

“But she’s paying you something, right?”

“Yes.”

“What?”

“Something.”

“Was just curious,” he said, hands flying up to underscore the harmlessness of his query. “Your girl takes a nice photo. Can I keep these?”

“No.”

“Guess I’ll have to get Timmy Boy to bring me some.” He wet his bottom lip. “Dangerous world out there. You hoping your girl turns up, nice and safe and sound?”

For the second time, I stood up. “I didn’t think you knew anything. Or would say if you did.”

Nichulls didn’t rise to the bait. “You afraid?” His tone was scornful, mock curious. “Think I’m bad, there’s people out there put me to shame. Believe you me.”

“What people?” I said.

“Real bad people.”

“Do you know what happened to her?”

Nichulls leaned forward and cleared his sinuses. One of the guards touched his shoulders, and Nichulls slouched back.

“Leaving now,” I said to the guards.

Kwan passed me the photos. From the look on his face, he seemed genuinely saddened that nothing had come from the meeting. That raised him in my estimation, though I didn’t share the feeling. It had gone the way I knew it would.

The killer had the last word.

“I’ll be here if you need me,” Nichulls said.

It was muggy and overcast as I drove back to the city. Even with the windows down and the odd spatter of rain dancing on my forearm, I was sweating. July in the Lower Mainland: the sun transient, the rain lukewarm and viscous.

I drove straight downtown, touched my pass to the sensor on the parking garage gate, and slid the Cadillac into its spot. Then I rode the elevator up to the office.

It had been a strange transition from self-employment to being one half of a partnership. Wakeland & Chen Private Investigations had a plush office suite in the Royal Bank building, on the stretch of Hastings where addicts and panhandlers are politely discouraged. We had several corporate clients and a full-time office staff, even if that staff was Jeff Chen’s second cousin Shuzhen. Gone was my cubbyhole of an office, with its cobbled-together furnishings, and the staircase that smelled perpetually of piss, no matter how often I bleached it. Partnering with Jeff Chen had turned my career around.

At the same time, I didn’t like dealing with white-collar types, other than to hand in my work and cash their checks. I don’t golf, I don’t schmooze, and when I drink it’s usually alone with my stereo. A smarter person would keep quiet and start saving for a Porsche. I was beginning to feel unsuited for about eighty percent of my profession.

Jeff was tolerant. He’d spent a decade navigating the corporate security world. He’d worked for Aries, a company so shady they could only call staff meetings during an eclipse, run by a crook who thought scruples were for the weak. Jeff knew I was eccentric, but also that I would deliver. A successful missing persons case netted the kind of publicity you couldn’t purchase.

So we struck a compromise: I was free to work the cases I wanted, provided I donned a suit and glad-handed every once in a while.

I dropped the mileage log on Shuzhen’s desk, then headed to my office to scoop the mail off my table. The only thing that had accompanied me on the trip to the profitable end of Hastings was that oak dining table, chipped and scarred and pocked with cigarette burns. Someone had once broken into my old office and set it on fire. That tank of a table had withstood the blaze, and I’d had it refinished. It still served as my desk, incongruent as it was with the tasteful, flimsy office decor around it now. Furniture that can survive arson has untapped potential.

My office door was unlocked. Standing inside with her back to the door was Marie, Jeff’s fiancée. She was a good person. I reminded myself of that as she turned and shot me a look that seemed to ask what business I had being here.

“When will you let me pick out a real desk for you?”

A witty rejoinder would only lead to squabbling. I shrugged. “I’m comfortable with it. What are you up to?”

“Seeing if you billed Gail Kirby.”

“Heading over there now.”

“Because it’s been a month already, and when I phoned she said she’d just received the invoice.”

“Heading over there now.”

“And I didn’t know if you’d been late handing it in, or if it was disorganization on her part.”

“I’ll give her the invoice today,” I said. “And I’ll tell her, cancer or no, she doesn’t pay within forty days I break her knees.”

“You do that,” Marie said. “Try to remember this is a business, not a charity. People who won’t do business aren’t worth doing business with.”

“You learn that at the School for Culinary Arts?”

My stupid mouth. Marie frosted over instantly.

“I’m twelve credits from my MBA,” she said. “And yes, before that I explored other career options. How well did you do in college, Dave, you want to talk academic achievement? What did you accomplish?”

“I drank a lot in libraries.”

I put the file on the desk. Marie looked at the photo of teenaged Chelsea Loam. Her face softened. “I thought this girl was a prostitute,” she said.

“That’s an old photo. Other than the street shot, the only others are from arrest reports. I don’t like using mug shots—gives the impression she’s a criminal, sends the wrong message.” I tapped the yearbook photo. “So does this one, but having people think she’s a doe-eyed innocent is better than seeing her as a harlot who got what was coming to her.”

“People think that?”

“People think a lot of shit,” I said.

Jeff came down the hall, spied us and turned in. He kissed his fiancée and took his sweet time coming back down to earth.

“You went and saw that asshole today,” Jeff said. “Anything useful?”

“It was a long shot. She worked in the same area where Nichulls took his victims, but so did a lot of people.”

“So it’s not Nichulls,” Jeff said. “What next?”

“Next is telling Gail Kirby it wasn’t him.” I looked at Marie. “And giving her the invoice.”

“And then back in the rotation?”

“More than likely,” I said. “She had the one anonymous tip about her daughter. Now that that’s a bust, there’s not much left to the case.”

“Good,” Jeff said. “Not good, but—you know what I mean. The VP of Solis Developments asked about you personally.”

“Goody.”

“They’re thinking of ditching their in-house security, taking up with us. Their boss, Utrillo, is on the fence. But the sales VP Tommy Ross is a fan of yours. Wants you to bodyguard him on his trip to Winnipeg.”

“Pass.”

“No passes allowed.”

“I hate Winnipeg.”

“Have you ever been?”

“It seems the kind of place I wouldn’t like.”

Jeff shook his head. “I do a lot of things I don’t like. For you this is mostly a vacation. Free plane, free hotel. While you’re out there you can see the world’s biggest Coke can.”

“No,” I said.

“They’re a big account, which makes them more important than a small account.” He held in his arms a thick file in a faux-leather accordion folder with a gold foil decal in the shape of a sun. He spoke to me in the voice you’d use for a small child or a large dog, pointing between the file in his arms and the open folder with the two photographs. “Big account. Little account. Little. Big. See how that works? If the big account is happy, you can afford to work on the little account. If not, then we’ll all need squeegees and cardboard signs.”

I said I’d think on it.

“And please get rid of the table. I will pay to replace it. Get a whole office suite.”

“There are some nice rosewood desks at the India Imports on Broadway,” Marie said. “You can use my discount.”

I waxed noncommittal and took the big brass elevator eight floors down to street level. Half the battles I fought, I fought only to fight them. Why not ditch the table? It was just something familiar.

On Hastings I unlocked my Cadillac and drove west down Seymour, working out what I’d tell Gail Kirby. I wondered what she’d expected from Nichulls. What she expected from me.

I looked at the file on the passenger seat, a corner of the black-and-white photo reaching out past the beige cardboard to graze the beaten leather. A few strands of black hair, the edge of a jawline.

Chelsea Loam.

I doubted very much we were done with each other.

Mrs. Gail Kirby once told me, “When I was calling Missing Persons every day to ask what they were doing to find Chelsea, they used to say, ‘She’s just a whore, it’s not like she’s anyone important.’ The first reporter I went to told me if Chelsea was the daughter of some gray-haired lady from Kerrisdale, everyone would put a lot more effort into finding her. Well, now I am a gray-haired lady from Kerrisdale, and before I finish I’m going to know what the fuck happened to my daughter.”

She’d come to me reluctantly, a month ago, prompted by her other daughter, Caitlin. “She thinks I’m not strong enough to face this monster,” Gail Kirby had said. “Caitlin should know what I faced in my time. But I see her point.”

Caitlin had thought the whole effort a waste. After my first meeting with her mother, she’d told me, “There’s simply no way Chelsea could be alive and not call us. Not with the amount of money my mother shelled out to her, unconditionally. No way she’d go all this time without coming back for more of that. Plus Gail loved her. Chelsea’s dead, she’s dead, and let that be the end of it.”

“But why hire me?” I’d asked.

“Because,” Caitlin had said. “Gail shouldn’t have to deal with people like that. Her life’s been arduous enough as it is. If this ‘clue’ is as bogus as it appears, she shouldn’t be tormented by Ed Leary Nichulls.”

The clue referred to a letter the Kirbys had received through the doggie door of their palatial house in Shaughnessy Heights. No stamp, nothing written on the construction-paper envelope. The envelope itself unfolded into a note written in blue magic marker. All caps: ASK SCRAPYARD ED ABOUT YOUR DAUGHTER.

False leads weren’t uncommon. The Ghoshes, other clients of mine, had received notes claiming if Mrs. Ghosh stood by her bedroom window naked, rubbing herself for three nights in a row, her daughter would be brought back. Jeff and I found the writers, a couple of high schoolers whose parents took a boys-will-be-boys attitude to the incident.

I parked my Cadillac in Gail Kirby’s driveway and headed to the door through a trellised archway. The clematis that weaved through it had bloomed ivory-colored flowers, but patches of the front garden remained dead heaps of brown and gray, last year’s untended bark mulch. Gardening was Mrs. Kirby’s very favorite hobby and she hadn’t been attending to it.

I let myself in. I found Gail and Caitlin in the solarium, playing cribbage and drinking Pimm’s. Gail smiled as I approached.

I gave her the news. It didn’t seem to dampen her spirits. Caitlin involved herself in her cell phone.

“It was worth a try,” Gail said. “Sit down for a minute.”

I sat in a white wicker chair and flicked a spider off the armrest. Watering cans and gardening supplies littered the tiled floor of the solarium. Bags of calcite and fertilizer, stacks of red clay pots, floral-patterned gardening gloves and a trowel and shears tucked into an overturned straw hat. All of it filmed with dust. One of the pots had been repurposed to accept cigarette butts. It lay next to Gail Kirby’s chair, beside her oxygen tank.

“Gail has something she wants to ask you,” Caitlin said. She didn’t look up. Her tone made it clear that she’d lost an argument on the same subject before I’d arrived.

Gail lit a cigarette and looked at her daughter with a mixture of sadness and pride. Only a parent could pull off such a look. She said to me, “What would you do, David, if you were working this case full-time? Where would you start?”

“With the police,” I said. “They have resources a private firm can’t compete with. I’d work up as much info on your daughter as I could from friends and family. At the same time I’d start with her disappearance and work backward. Find out who she worked with, lived with, who she went to for help. A lead might emerge. But I’d start with the police.”

“The police don’t care,” Caitlin said.

“Lot of cases they’re effective, whether they care or not.”

“I care,” Gail said. “I have the money. Would you put up a reward if you were me?”

“No, but I’d pay for information. Let people know a solid lead is worth money, but keep the scammers and lunatics away.”

“I want Chelsea found,” Gail Kirby said. “I’m prepared to pay.”

“Money pissed away,” Caitlin muttered.

“There will be plenty left for you when I’m gone,” Gail said.

“That’s unfair.” Caitlin pushed away from the table and made a show of tossing her cards in. “Know what? I refuse to deal with this any longer. I’ve got a life of my own.”

As she stormed out, Gail said to me, “She may have a point.”

“There’s no guarantee,” I admitted. “And it’s not cheap.”

“I don’t care about the money. Do you know how it came about, this fortune?” She took a whiff of oxygen and set the mask back on the table’s edge. “Lew—my husband—died in an industrial accident on an oil rig in Fort St. John. The settlement was generous. Caitlin had finished school and Chelsea had left us. I put all of it into real estate. This was before the housing boom. Now I’m worth skillions.”

She crushed out her cigarette on the glass table and consigned it to the pot with the others. “And now I have cancer,” she said. “Stage three. It’s not going to get better. I want my daughter found, David. Chelsea only lived with us for five years, but she’s as much my daughter as Caitlin is. It kills me not to know. And since I have this money, I’m going to use it.”

“It’s been eleven years,” I began.

“I know she’s probably dead. I have no illusions. I just need to know.”

Gail took an envelope from the pocket of her button-up sweater. She meant to sail it across the table to me, but her strength failed and it glanced off the pitcher in the middle of the table. I reached over. Inside was a check for two hundred thousand dollars.

“Your time and expenses,” she said. “You find her or what happened to her.”

“I can’t take that much from you,” I said.

“Sure you can.”

I pushed the invoice toward her. “Pay this and I’ll draw up a contract.”

“And you’ll find her?”

“I’ll do my level best.”

“Do everything,” she said.

Caitlin was waiting in the driveway. I’d boxed in her Beemer, but she lingered by the side panel of my Cadillac like she wanted some words. I’d had enough of words for the day, but it wasn’t my choice.

She eyed the Cadillac, a decade-old XLR in dire need of a wash, like it was the model of conspicuous consumption. “You probably have a fleet of these made off of swindling old ladies like my mother.”

“Let me ask you a question,” I said, opening the door and resting an elbow on the roof. “What do you think it’s worth, finding your sister?”

“She wasn’t my sister,” Caitlin said.

“But what price would you allow your mother to put on that?”

She shook her head. “It was my idea to hire you. Otherwise Gail would’ve had to follow up on this mess herself. She didn’t think you were necessary. Now,” she said, “she thinks you’re worth two hundred thousand dollars.”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

“It doesn’t matter because you’re not going to find her because she’s not around because she’s dead. Something happened to Chelsea.”

She paused and turned to examine an unkempt rose bush in the front yard. Wilted yellow petals, tendrils of thorns snaking out across the path. I waited her out.

“Chelsea messed up everything,” she said. “Everything she touched. Even my mother knows it deep down. Hiring you is only out of guilt for Gail finally being happy—which she won’t be for much longer if the doctors are right.”

“How long does she have?”

“She doesn’t tell me those kinds of things,” Caitlin said. “She doesn’t want me to worry. That’s a laugh, isn’t it?”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“It’s simply how it is,” Caitlin said. “What it means to you is if you’re going to swindle her, you’d best do it in the. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...