- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

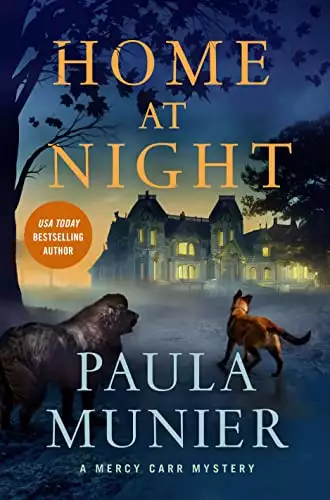

Synopsis

Beware the blackbirds…

It’s Halloween in Vermont, winter is coming, and five humans, two dogs, and a cat are a crowd in Mercy Carr’s small cabin. She needs more room—and she knows just the place: Grackle Tree Farm, with thirty acres of woods and wetlands and a Victorian manor to die for. They say it’s haunted by the ghosts of missing children and lost poets and a murderer or two, but Mercy loves it anyway. Even when Elvis finds a dead body in the library.

There’s something about Grackle Tree Farm that people are willing to kill for—and Mercy needs to figure out what before they move in. A coded letter found on the victim points to a hidden treasure that may be worth a fortune—if it’s real. She and Captain Thrasher conduct a search of the old place—and end up at the wrong end of a Glock. A masked man shoots Thrasher, and she and Elvis must take him down before he murders them all. Under fire, she and Elvis manage to run the guy off, but not before they are wounded, leaving Thrasher fighting for his life in the hospital, Mercy on crutches, and Elvis on the mend.

Now it’s up to Mercy and Troy and the dogs to track down the masked murderer in a county overflowing with leaf peepers, Halloween revelers, and treasure hunters and bring him to justice before he strikes again and the treasure is lost forever, along with the good name of Grackle Tree Farm….

A Macmillan Audio production from Minotaur Books.

Release date: October 17, 2023

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Home at Night

Paula Munier

HALLOWEEN, 2004

GRACKLE TREE FARM, VERMONT

The moon shone dimly through the fog that night. Dusk fell quickly, shrouding the old manor in shadow. The ivy-covered Victorian stood dark and silent under a towering maple, Bear Mountain hulking on the horizon. One hundred and fifty years of history and mystery lurked within the house, and as she crept along the brick path that led to the heavy front door, Mercy Carr cursed the boy who’d dared her to come here and her own reckless curiosity for accepting that dare.

A rapid-fire crackling—ki ki ki!

Mercy swallowed a scream as grackles stormed the sky above her, whirring and wheeling and whirling as one until they hurtled into the thick branches of the big maple. A shuddering of leaves. A whistling of beaks. A rustling of feathers.

Silence once again.

There must be a thousand grackles in that tree, thought Mercy. As forbidding as the manor was, she’d rather face a million shrieking specters inside its gloomy walls than spend another minute out here with these yellow-eyed demons. Or maybe she should just go home. Maybe her mother was right, and she was too young to be reading all that gothic literature.

But she loved all those macabre poems and stories—and the opportunity to spend the night in a real-life haunted house was too good to pass up. Especially one whose most celebrated spirit was the subject of one of her favorite poems: “The Ghost Witch of Grackle Tree.”

This was the house where the woman who’d written it had lived. Her name was Euphemia Whitney-Jones, and her family still owned this estate. The old Victorian sat empty now, as it had for years, neglected by them and ignored by most everyone else.

Except on Halloween, when local teens and out-of-town ghost hunters tried to catch sight of the witch, who was said to wander the grounds on this night every year. Mercy’s classmate Damien—a pain on a good day—had challenged her to come here tonight and meet the ghost. He’d never let her live it down if she chickened out.

She looked for the spare key he’d told her about—and found it under a stone lying at the foot of one of the huge hydrangeas that flanked the entrance. Mercy wouldn’t be surprised if Damien was hiding inside somewhere. It would be just like him to lie in wait, hoping to leap out at her and scare her silly.

She didn’t frighten that easily. Her big brother, Nick, with his newly minted driver’s license, had dropped her off here, thrilled for the opportunity to run the hairpin turns up to the remote property. He’d offered to go inside with her if she wanted. But she’d sent him on his way to join his friends in the nearby woods, where they’d drink beer and do stupid boy stuff. Mercy didn’t need a bodyguard. She could take care of herself. And she was armed with a small volume of Euphemia Whitney-Jones’s poetry, her talisman against evil spirits.

She unlocked the heavy front door and pulled it, hard. Nothing. She pulled again, harder. And once more. The door creaked so loudly when she finally managed to move it that she had to steel herself not to jump. She stepped into the entry, flicking her flashlight around the hallway and up and down the staircase. All very beautiful, very creepy, very desolate. A Miss Havisham of a house.

Mercy sidled into the formal parlor, a ruin of a room with blotchy red flocked wallpaper. No witch, just dust and grime and spiderwebs. She wondered why no one lived here anymore. Somebody should buy this house and fix it up. That’s what she’d do if she were a grown-up. Embrace it, grackles and ghosts and all, and move in to stay. Restore it to its former glory. A place of magic and poetry.

She heard the distant din of voices, and thought she recognized Damien’s scornful laugh. She ducked into the kitchen. When the chatter seemed to follow her, growing louder with every step, she stumbled into the pantry, slamming the louvered doors behind her. A tin canister of flour fell from the top shelf, the top falling open, banging her forehead and dousing her in white powder. Sticking to her hair, her cheeks, her lashes, her lips. Even her sweatshirt and her jeans.

She yowled in surprise and clouds of the yeasty stuff slipped into her mouth. She needed to cough, but she didn’t dare. She tried to hold her breath to keep from wheezing. She heard footfalls and disembodied voices in the kitchen, saw slivers of faces and bodies through the louvered doors as beams of light bounced around the room.

She switched off her flashlight. Shuffled feet and muffled mutterings headed her way. She blinked away the white powder that fell into her eyes, and more flour fell in. She blinked again.

A jerk of the handle and the door bounced open. A glare of light blinded her; someone screamed. The giggling ghostly figures advanced upon her. A loud boom silenced them—and Mercy realized it was the sound of her own falling, falling, falling to the floor of the pantry. The last thing she heard before she passed out was the clatter of the kitchen visitors scattering like so many blackbirds.

Mercy didn’t know how long she was out. Long enough for a chill to set in and goose bumps to appear along her pale arms. Her head ached; she could feel a bump forming on the left side of her brow. She listened for sounds of life outside the slatted doors.

The silence of the old house was overwhelming. She could hear nothing but the pounding in her head. She counted to one hundred and back down to one again, just to make sure that no one was coming back.

She tried to brush off the white stuff clinging to her person from head to toe, but it stuck too fast and took too long. She gave up and slipped out of the pantry, passing though the empty kitchen and leaving by the back door. Forget Damien, forget dares, forget gothic novels.

Mercy ran, crazily, into the dark, her flashlight forgotten, a bouncing strobe on her hip. As she passed under the towering maple full of grackles, she stared up into its elephantine branches, expecting to see hundreds of glowing pairs of yellow eyes.

“Stop!” came a roar from nowhere and everywhere.

Mercy collided with a tall figure in flowing, glowing white garb and screamed, a full-out howl of fright. She tried to push the diaphanous thing away, but it took her by the shoulders with its large white-gloved hands and held her in place. She twisted in its hold, but it held firm.

“Calm yourself.” Something about the voice, with its low-pitched Yankee grumble, struck a discordant note. Mercy stared at the creature before her, with its dark eyes gleaming through the veil. Was this the fabled Ghost Witch of Grackle Tree?

The creature looked pretty real to Mercy. In fact, as she peered at the face obscured by the filmy veil, she realized that this was not a ghost or a witch or even a woman. Under the girly dress and the waist-length platinum wig was a man. An honest-to-goodness human male.

“Who are you?” she whispered.

“I’m the witch.”

“No, you’re not.”

The creature laughed—an odd heh heh heh staccato—but did not correct her. “You dropped this.” He let go of her shoulders and pulled her little book from a hidden pocket in his voluminous skirt. He handed it to her.

“Thank you.” Mercy slipped the volume of poetry into her pocket. She was glad to have it back. Proof that what was happening to her was not a figment of what her mother called her overactive imagination.

“Everything you need to know is in her poems.” And with that, he retreated into the shadows of the mammoth maple. “Home at night you’d better be.”

“Right.”

He was gone. She looked around her, but all she could see was darkness.

Mercy withdrew the flashlight from her belt and shone it around the property. She heard shouts from inside the house. Time to go. She ran for the woods and didn’t stop to look back until she reached the edge of the forest.

In the dim illumination of the flashlight, the backside of the manor looked as bleak and beautiful as the front. There, on the wide back porch, stood a ghostly figure in a long white gown reaching after her, slender arms and pointed fingers glowing, as if to pull Mercy back to the house. It could have been the same creature that gave her back her book, but she couldn’t be sure. This one seemed more ethereal, more feminine, more otherworldly than the so-called ghost witch she’d encountered under the grackle-filled tree.

It was colder now, or maybe that was just the fear talking. For it was only now that she felt truly anxious. Mercy shivered, shoving her hands in her pockets. She felt the book, which seemed bulkier than she remembered. She retrieved it, and that’s when she noticed the bulge in the middle. She opened the book, and there lay a stone with a hole in the middle. It had not been there before. The stone was a gift. A gift from a ghost.

Or not.

The eerie caws of the grackles sounded above her, and she looked up at the screeching. A barred owl swooped past her, flapping its enormous brown-and-white feathered wings in a rush of cool night air. A sign, like the poem and the witch and the stone. A sign that this house was meant to be home to more than blackbirds.

Mercy fingered the flat rock in her open palm. Maybe someday …

CHAPTER ONE

Are we not homes? And is not all therein?

—CHARLOTTE ANNA PERKINS GILMAN

There are many places we can call home, and the longer we live, the more places we will call home. This was a lesson that Mercy Carr kept learning over and over again. First in the military, and now in civilian life.

The good news was that she and her new husband Troy had found the perfect house to call home. A mid-century post-and-beam lodge in the woods, big enough for Mercy and Troy, the dogs, the cat, and Amy and Helena, the young teenage mother and child Mercy had met during a case and taken in afterward. The bad news was that the deal had fallen through at the last minute, thanks to squabbling siblings, one of whom pulled out just before closing. And just after Troy had sold his converted fire tower to the State of Vermont.

Now there were three animals, one child, three adults—well, four if you counted Amy’s boyfriend Brodie, who practically lived here anyway—all squeezed into Mercy’s cozy, if small, cabin in the Green Mountains.

“You need to move.” Her mother Grace sat next to her in one of the two rocking chairs on the front porch of the cabin, regarding Mercy with her signature I’m your mother and your attorney so listen up look.

“We bought a house.” Mercy stroked Muse, the sweet little Munchkin kitty she and Elvis had rescued from a crime scene a couple of years ago. Muse was curled up in her lap for her usual post-breakfast nap.

“Breach of contract. Get over it and go find another one.”

“Easier said than done.”

“Since when do you like easy?”

Mercy laughed. Like most mothers—and this was the only way in which her mother was like most mothers—Grace knew her child too well.

“I have to love it.” Like she loved her cabin, where she and Elvis had come to get on with their lives after Afghanistan. Both she and the bomb-sniffing shepherd had been mourning the loss of her fiancé, Martinez, who was also Elvis’s handler. He had died in the same battle that left Mercy wounded and Elvis traumatized. This cabin, with its massive fieldstone fireplace and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and a wall of windows looking out at the woods, had been a comfort to her and to Elvis.

She’d never thought there’d be another man she could love like Martinez—and then she met Troy. Mercy couldn’t believe her luck.

She’d never thought there’d be another place she could love like this—and then they found the lodge. Her good luck was holding.

And then they lost the lodge. And now she and Troy had to start all over again. So much for luck. Mercy sighed. “The lodge was the perfect property.”

“There is no such thing.” Her mother tapped on the front window of the cabin behind them. “It’s a nightmare in there. Too many people, too many animals, too many books and moving boxes and clothes and toys and other paraphernalia. Too much stuff. You can’t escape outside to this porch forever. Winter is coming.”

“I know.” Mercy whistled for Elvis, who was making his daily morning patrol of the perimeter. She needed backup, and the former bomb-sniffing Malinois was one of the few sentient beings immune to her mother’s imperious charm. Grace neither impressed nor intimidated Elvis. Mercy loved the dog for that—and so much more.

Elvis came racing down from the barn, ears perked. The loyal Belgian shepherd could never ignore her whistle. But he could ignore her mother. He settled into a graceful sit at Mercy’s side without so much as a sniff in Grace’s direction. Nothing better than a cat in your lap and a dog at your feet, was Mercy’s way of thinking. Especially when talking to your mother.

“Then you need to get back out there,” Grace went on. “I’d be happy to help.”

The very thing Mercy most wished to avoid. She scratched the shepherd’s sleek head, trying to buy time.

“The first thing you need is a new Realtor.” Grace leaned toward her. “A good one would have seen that family quarrel coming, and steered you to another property. I could sue on your behalf.”

“Not necessary.” Her mother believed that litigation solved all ills.

“You should use that woman who sold Troy’s place.”

“Jillian Merrill?” Mercy had known her—or known of her, at least—when she was a teenager. Jillian Rosen then.

“She closed Troy’s deal in record time. To the State of Vermont, a government entity, no less.”

“I know.” Her husband had sold his one-of-a-kind converted fire tower without a second thought before they even found the lodge. And even after they lost the lodge, his faith that they would find a wonderful new home together never wavered. Even as hers was wavering right now.

Her mother waited. Waited for her to admit her loss of faith. Instead, Mercy surveyed the garden in all its glory: black-eyed Susans, purple asters, and pink bee balm against a blaze of orange and gold maples.

“It’s a seller’s market,” Grace finally said. “The best properties are going fast.”

“That’s why I’m in no hurry to list the cabin. We need a place big enough for all of us. If the cabin sells before we’ve found something, we could all end up spending the winter in a trailer.” She knew this was her chic mother’s idea of hell.

“You know it doesn’t have to come to that.” Grace crossed her legs, careful not to crease her caramel-colored tweed trousers. She’d gone full-on Ralph Lauren for the fall season. “You don’t need such a big place. You don’t have to sell the cabin. Amy and Helena can stay here, and you and Troy can find something that’s right for you. There are a lot more medium-sized properties to choose from.”

Mercy didn’t say anything. She’d heard this argument before. All her adult life, really.

When she’d found the cabin, her parents had offered to buy it for her, as had her grandmother Patience, but like a good soldier, she’d insisted on purchasing it herself through a VA loan. Likewise, they’d all offered to buy her and Troy a house, too, and God knows they could more than afford it. But Mercy had refused. And she would keep on refusing.

Her mother frowned. “That pride of yours will be the death of you someday. Just like your grandfather.”

Mercy’s beloved grandfather was a sheriff who died in an arrest gone wrong, because he didn’t wait for backup. He was a proud man, and Mercy admired him for it. If she was like him, then she was glad of it.

“You think that to maintain your autonomy, you have to do everything by yourself. But you don’t,” Grace went on. “It’s bad enough that you won’t let us help you. Don’t make that mistake with your husband. You’re not a one-woman band anymore—you’re a team now.”

“I know that.” Mercy scratched the shepherd’s ears. She knew how to be part of a team. The military was all about esprit de corps. And since she’d come home from the war, she and the shepherd had worked through their troubled past together. When she and Elvis met Troy and his search-and-rescue dog Susie Bear, the four of them became a team in work and in love and in life.

“Then act like it. If you insist on selling the cabin, then list it now. Maybe that will get you off this porch and into ‘Open Houses.’”

“Troy’s fire tower and my cabin are both very special homes. I don’t want to be forced to settle for something mediocre just because we got married.”

“According to Lillian Jenkins, you’ve seen practically every property currently on the market.”

This was true. Mercy had no defense other than the expected one. “Nothing I could fall in love with.”

“Is that your only criterion? Or are you waiting for a sign?”

Mercy knew her mother didn’t believe in signs. But soldiers were a superstitious lot, and signs were as much a part of the military as bad food and battle drills. She thought of signs as synchronicity, little coincidences that could point to larger truths if you were paying attention. Mercy tried to pay attention.

Elvis leapt up and took off, tearing down the garden path, sliding to an elegant stop at the edge of the driveway. He settled into his happy waiting stance, black-tipped tail up and wagging hard. Mercy grinned at the sight of her grandmother’s oversized yellow van barreling up her driveway and coming to a stop behind her mother’s blue Volvo. Patience was a veterinarian, and the Nana Banana was her fully equipped mobile clinic.

Elvis greeted his favorite vet with a quick yip as she exited the van. The Malinois adored her grandmother, as did most species, domesticated and undomesticated. Patience hurried up to the porch, a Tupperware container in her hand, Elvis on her heels.

Mercy rose to her feet in alarm. Patience was not the sort to rush, especially when transporting baked goods.

“Mother?” Grace remained seated, but Mercy could hear the worry in her voice.

“Is everything all right?” asked Mercy.

“Just fine. But you need to get a move on.” She offered up the plastic tub.

“Why?” Mercy pulled up the top of the Tupperware to sneak a peek. Just as she’d hoped: her grandmother’s famous cinnamon rolls. “Thank you!”

“Lillian sent me. Grackle Tree Farm is going on the market.” Lillian Jenkins was her grandmother’s best friend and the grande dame of Northshire. If there was news to know, she’d know it first—and spread it fastest.

“Now, that is a very large property.” Her mother glided to her feet. “Let’s get those rolls inside.”

Mercy ushered her mother and grandmother into the cabin. “Have a seat. I’ll get us some coffee. Who wants a roll?”

“No, thank you.” Grace never ate any of her mother’s amazing desserts. How she resisted, Mercy had no idea.

“They’re all yours, love.” Patience settled into a chair at the farm table across from Grace. Elvis stretched out at her side, his head on her boots. He adored his vet. “The house itself is a historical gem. One hundred and fifty years of history behind it. And you love old houses.”

“True enough.” Mercy poured coffee into three mugs, and brought them to the table on a small tray, along with cream and sugar and a roll for herself.

“I’ve heard it’s a mess,” warned her mother. “And then there are the grackles.” She sipped her coffee, which of course she took black.

“Grackles are fine, intelligent blackbirds.” Patience defended the birds with the confident air of the real expert in the room as she added sugar and cream to her coffee. “Their bad reputation is undeserved. They’ve earned the enmity of farmers because they feed on crops like sorghum, wheat, corn, all the grains. But they’re really great for your garden, as they eat lots of insects. Just don’t grow corn.”

Grace was not impressed. “They’re the hyenas of birds. They make a horrendous racket. And they’re the bullies of the bird feeders.”

“Mercy knows better than to put out bird feeders.” Patience looked to Mercy for confirmation.

“Indeed I do.” At this time of year, bird feeders attracted bears as well as birds. Which never ended well for the bears. Responsible Vermonters drew birds to their gardens with flora, not bird feeders.

“Go ahead, show off your new knowledge.” Patience had encouraged her to go back to school to get her degree in wildlife management more than anyone else in her family, apart from Troy.

“Grackles are an essential link in the food chain.” Following her grandmother’s example, Mercy added generous amounts of cream and sugar to her coffee. “They eat most anything—plant and animal—and hawks and owls and foxes eat them.”

“I stand corrected,” said Grace. “Apparently blackbirds are one of this property’s biggest assets.”

“It’s a house full of mystery and drama and poetry.” Patience looked at Mercy. “Enough to satisfy even your inner Shakespeare.”

“Also true.” Mercy hadn’t been out there in years, but she remembered the place well.

“‘The Ghost Witch of Grackle Tree.’”

“Of course!” Her mother laughed. “You were obsessed with that poem as a teenager—and everything else that woman wrote.”

“Euphemia Whitney-Jones.” Patience gave Mercy a knowing look.

Her grandmother was the only grown-up she’d told about meeting the witch all those years ago. Of course, everyone in middle school knew about it. She’d brought the holey stone to school, regaling her classmates with her encounter with the witch and showing off the present she’d given her. Much to Damien Landry’s dismay. She’d left out her discovery that the so-called poltergeist was really a brown-eyed man in a silver-white wig with a weird laugh.

That was then, this is now. Mercy looked out the large windows, staring past the lavender that lined the footpath to the flagpole in the middle of the garden, where the American flag flew night and day, in honor of her fallen comrades. Yes, she believed in ghosts. Not the horror-story kind of demons or the ghost witches of poems, but the spirits of the warriors who visited her in her dreams. “I do believe in ghosts.” She stood up. “But I’m not afraid of haunted houses.”

“Every house is haunted by something,” said Patience.

“It would be perfect for you and Troy. It’s large enough for you and your dogs and all your strays and a couple of children of your own, too. Go look at it. Buy it.” Grace finished her coffee, and rose to her feet, her trousers falling neatly into line. “I have a luncheon to attend.”

“I can’t stay, either.” Patience gave Elvis a pat. “Got a rabies clinic to run in Rutland. I promised Lillian you’d meet Jillian Merrill at the house in thirty minutes.”

“A real Realtor.” Grace headed toward the door, and the rest of them followed her out to the porch.

“Apparently the owner is anxious to sell,” said Patience. “And if you don’t buy it first, the poets will want it for a museum, the builders will want it for McMansions, and the developers will want it for God knows what kind of monstrosities.”

“That would not be good.”

“Go save a historic Vermont landmark. Live among the dead poets. You know you want to.”

“Amen.” Grace swept past them onto the gravel path toward her Volvo, wiggling her long fingers goodbye.

“Thirty minutes.” Her grandmother kissed her on the cheek, stroked Elvis’s ears, and started toward the driveway. “I’ll tell Lillian you’re on the way.”

Mercy and Elvis watched as the blue Volvo and the Nana Banana roared off in reckless succession. Speed being the one thing that her mother and her grandmother had in common.

The shepherd nudged her hand with his nose.

“I know, I know.” She grabbed a cinnamon roll for the road. “The clock is ticking.”

Elvis was ready to go. He wasn’t afraid of ghosts, either.

* * *

LEVI BEECHER WATCHED THE man in the fancy leather jacket as he examined the low-hanging branches of the big old sugar maple behind the manor house at Grackle Tree Farm. He knew the man’s name was Max Vinke, and he knew he was from California. The trustee had told him that Vinke was checking out the place for Maude, the last remaining member of the Whitney-Jones family. But Levi suspected that he’d really been sent by Maude to dig up all her sister Euphemia’s secrets. Secrets long buried all these years. And they would stay buried—Levi would see to that.

Vinke couldn’t see him behind the thicket of red osier dogwood; the Santa Barbara snoop didn’t realize he was under observation. Levi was good at hiding; after fifty years as caretaker here, he knew every inch of this property. And he was good at observing people; he’d much rather watch people than talk to them.

Vinke kicked the thick trunk of the tree. Frustrated, no doubt, by the search that was leading nowhere. At least for now. But Vinke was a good private detective, according to the testimonials on his website. And Yelp. If he persisted, he might figure it out eventually.

Levi knew that Vinke had done his homework. He’d started with the poetry. He’d even gone to the Northshire Alliance of Poets celebration last night. Levi himself usually avoided the pretentious get-togethers, but his sister Adah was up for the Euphemia Whitney-Jones Poetry Prize, and he wanted to be there to support her when they gave it to someone else. Someone writing “stately stanzas of dazzling virtuosity.” Which is how that blowhard Horace Boswell had praised the winner’s poems when he presented the prize. Not to his sister, but to another self-important academic like himself. Big surprise there.

Levi loved poetry, but he hated poets. In his experience, the greater the poet, the lousier the human being. Except of course for Euphemia Whitney-Jones. And his sister Adah.

The fact that the most illuminating poems were often written by the most unenlightened people always exasperated Levi. At the party, Horace and his hangers-on were in rare form, basking in the attention of the so-called film scout from LA—aka Max Vinke—like starlets soaking up the sun at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool.

Like movie people ever made movies out of poems. Apart from The Odyssey. Which he doubted many of those in attendance had actually read the whole way through.

Levi followed Vinke from the old maple to the manor house. Maude must have given the private detective a set of keys, because he let himself into the house. He didn’t lock the door behind him.

While Vinke searched the downstairs, Levi remained at the front entrance behind one of the tall cedars that anchored the front façade of the house. He knew for sure the investigator would find nothing there. Eventually, the guy must have reached that same conclusion himself, because he abandoned his exploration of the first floor and climbed the staircase to the second floor. Levi counted to one hundred, then sneaked inside and stole up the stairs quietly, avoiding the creaky spots. Quiet as a bobcat in his rubber-soled duck boots.

The library door, which was always kept locked, was wide open. If there was anything to find in the house itself, Effie’s library was the logical place to look. Vinke was right about that.

But Levi wasn’t worried. He, not the estate, was the keeper of Effie’s secrets. He sneaked back down the stairs and out the door, headed for the barn. As he left, he looked up at the windows of the library on the second floor.

Knock yourself out, California, he thought. There was only one way anyone would ever learn the confidences Euphemia Whitney-Jones had kept so close to her heart.

Over his dead body. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...