- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

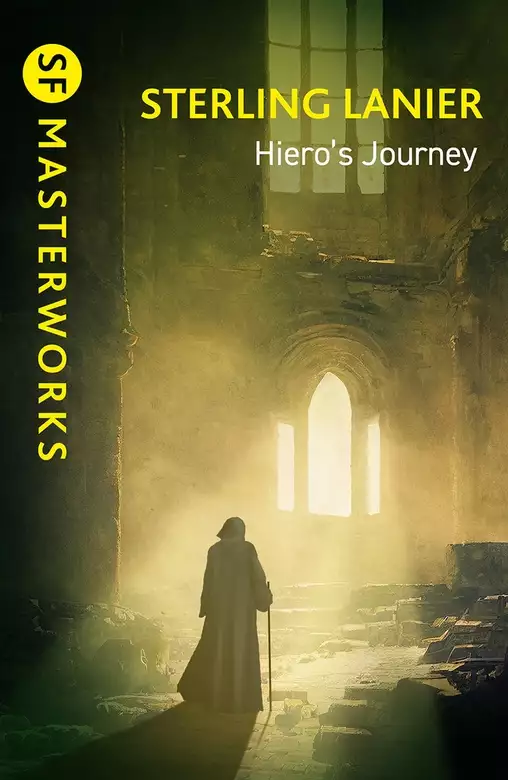

Synopsis

The world ended. People survived.

Per Hiero Desteen was a priest, a telepath-and a highly trained killer.

Five thousand years after the apocalyptic event known only as The Death, Hiero is tasked with finding the secrets of the old world, which could protect his civilisation from massing enemies.

The planet is not the same as it used to be. Mutations have changed the way humans and animals live together, the holocaust known as The Death. The Brotherhood of the Unclean wants to wipe out all traces of surviving human society, allowing anarchy to rule the wasteland that once was North America.

Hiero's journey takes him into the heart of the Brotherhood's territory. The danger is great if he is caught . . . but even the smallest chance that humanity could be saved is worth the risk.

Release date: January 1, 1974

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hiero's Journey

Sterling E. Lanier

While some of the science fiction of the Cold War period directly addresses the nuclear Armageddon and the days immediately afterwards, Hiero’s Journey belongs to the post-holocaust subgenre concerned with struggles of future generations to understand their history and remake or rediscover what has been lost in the nuclear fires. Its eponymous hero is on a quest for such knowledge, one of six warrior priests tasked with finding pre-holocaust computers, deemed essential for the defence of civilisation against armies of mutated animals and their Unclean masters, who use a combination of ancient technology and weaponised psychic powers to destroy all who threaten them. Although it’s set a mere 5500 years after The Death of nuclear war, Lanier’s novel, with its sword-wielding hero, ruined lands, monstrous creatures spawned by radiation-induced gigantism, enigmatic remains of ancient technologies and civilisations and psychic variations of magic powers, has much in common with far-future Dying Earth fantasies like Jack Vance’s collection of short stories which gave the subgenre its name, M. John Harrison’s Viriconium series, or Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun. And like Severian, the exiled hero of Wolfe’s tetralogy, Hiero starts out as an archetypal lone male protagonist, but in the course of his adventures acquires a small group of allies and a deeper understanding of himself and his world. He’s bonded, through a form of telepathy, with a morse, a kind of moose that’s replaced long-extinct horses, and uses the same power to befriend a helpful and unusually intelligent young bear. A little later, like Perseus (or King Kong), he rescues a princess, Luchare, who has been captured by barbarians and exposed as a sacrifice to monsters, and later still is rescued in turn by a sage from the brotherhood of the Eleveners, whose creed, based on an addition to the Ten Commandments – ‘Thou shalt not despoil the Earth and life thereon’ – provides an ethical framework for the proper use of the knowledge he is seeking.

While working as an editor for Chilton Books, Sterling Lanier persuaded his employer to take on Frank Herbert’s Dune after it had been rejected by more than twenty publishers. Dune failed to sell in its first printing, and Chilton (which mostly published auto repair manuals) wrote it off as a bad investment and fired Lanier, but he was, of course, later proven right. And as in the novel he championed, ecology and superheroes equipped with psychic powers are major elements in his world-building. Hiero is embroiled in a string of increasingly challenging telepathic battles with the Unclean, and although it’s populated by improbable monsters, from giant lampreys and seabirds to quasi-intelligent slime moulds and mutated man-rats, Lanier’s post-nuclear future is grounded in the geography and natural history of the regions either side of the border between Canada and the United States, and richly detailed depictions of their forests, swamps and lakes. It’s also, for its time, unusually inclusive; a satirical inversion of contemporary racial hierarchies. Luchare is of African-American descent, Hiero is Métis, with a mixture of indigenous and European ancestry, and the Elevener sage and other allies are likewise people of colour; but their enemies, from barbarians and cannibal hordes to the Unclean, are pale-skinned. In this post-holocaust future, the subaltern have inherited the Earth, and the Unclean are attempting to overthrow their polities and reimpose the ancient, pre-holocaust order.

Other works by Lanier include a contemporary fantasy, The War for the Lot, a sequel to Hiero’s Journey (a third volume, completed after his death by his god-daughter, is as yet unpublished), and a near-future planetary romance, as well as two collections of tales, recounted in club story style, of the cryptozoological adventures of Brigadier Ffellowes. Like those stories, Hiero’s Journey is a tale whose narrator is very much present; a yarn told con brio, with authorial asides and infodumps and footnotes, an exuberance of exclamation marks, and a plethora of sword-and-sorcery and Golden Age science-fantasy tropes deployed with spirited humour and a considerable dash of irony. This is, after all, a novel in which the hero is named Hiero Desteen (that is, destiny), and sets out on his Campbellian Hero’s Journey astride a telepathic moose. There are also some lovely passages of wonder and Lovecraftian cosmic dread, including this throwaway description of a power that haunts one of Lanier’s foetid, insect-ridden swamps:

At this dree hour came the Dweller in the Mist. The ghastly cosmic forces unleashed by The Death had made the mingling of strange life possible and beings had grown and thought which should never have known the breath of life. Of such was the Dweller … Around the corner of the next islet of mud and reeds came a small boat. It was hardly more than a skiff, of some black wood, with a rounded bow and stern. On it standing erect and motionless, was a figure swathed in a whitish cloak and hood. What propelled the strange craft was not apparent, but it moved steadily through the oily water, coming straight for the place where the priest now sat staring.

Like the most famous and influential post-nuclear war quests for renewal, Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, Hiero’s Journey views the powers of science as morally neutral, a toolkit that can be used for good or misused for ill. But while exploitation of scientific and technological advances by their flawed human creators feeds inevitable cycles of enlightenment and destruction in Miller’s novel, Hiero’s Journey is more hopeful. At the end of Planet of the Apes, adapted from Pierre Boulle’s novel La Planète des Singes, Charlton Heston’s stranded astronaut discovers the battered remains of the Statue of Liberty half-sunken in a beach, realises that his spacecraft timeslipped and crashed on Earth long after the Third World War, and cries out in amazed horror, ‘You blew it up! Damn you! Goddamn you to hell!’ We also blew it up in Hiero’s Journey, but maybe, Lanier says, we don’t have to do it again. History may not be destined to repeat itself in endless futile cycles. Like Hiero, we can learn to be better, and although the world is not as it once was, its new lands and creatures are as rich and strange as any before the nuclear holocaust. As the teachings of Hiero’s Elevener ally imply, life finds a way.

The Computer Man, thought Hiero. That sounds crisp, efficient, and what’s more, important. Also, added his negative side, mainly meaningless as yet.

Under his calloused buttocks the bull morse, whose name was Klootz, ambled slowly along the dirt track, trying to snatch a mouthful of browse from neighboring trees whenever possible. His protruding blubber lips were as good as a hand for this purpose.

Per Hiero Desteen, Secondary Priest-Exorcist, Primary Rover and Senior Killman, abandoned his brooding and straightened in the high-cantled saddle. The morse also stopped his leaf-snatching and came alert, rack of forward-pointing, palmate antlers lifting. Although the wide-spread beams were in the velvet and soft now, the great black beast, larger than any long-extinct draft horse, was an even more murderous fighter with his sharp, splayed hooves.

Hiero listened intently and reined Klootz to a halt. A dim uproar was growing increasingly louder ahead, a swell of bawling and aaahing noises, and the ground began to tremble. Hiero knew the sound well and so did the morse. Although it was late August here in the far North, the buffer were already moving south in their autumn migration, as they had for uncounted thousands of years.

Morse and rider tried to peer through the road’s border of larch or alder. The deeper gloom of the big pines and scrub palmetto beyond prevented any sight going further, but the noise was getting steadily louder.

Hiero tried a mind probe on Klootz, to see if he was getting a fix on the herd’s position. The greatest danger lay in being trapped in front of a wide-ranging herd, with the concomitant inability to get away to either side. The buffer were not particularly mean, but they weren’t especially bright either, and they slowed down for almost nothing except fire.

The morse’s mind conveyed uneasiness. He felt that they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Hiero decided not to delay any longer and turned south off the trail, allowing Klootz to pick a way, and hopefully letting them get off at an angle to the oncoming buffer.

Just as they left the last sight of the road, Hiero looked back. A line of great, brown, rounded heads, some of them carrying six-foot, polished, yellow horns, broke through the undergrowth onto the road as he watched. The grunting and bawling was now very loud indeed. An apparently endless supply of buffer followed the huge herd bulls.

Hiero kicked the morse hard and also applied the goad of his mind.

Come on, stupid, he urged. Find a place where they’ll have to split, or we’ve had it.

Klootz broke into a shambling trot, which moved the great body along at a surprising rate. Avoiding trees and crashing bushes aside, the huge animal paced along through the forest, looking deceptively slow. Hiero rode easily, watching for overhanging branches, even though the morse was trained to avoid them.

The man’s leather boots, deer-hide breeches and jacket gave him a good deal of protection from the smaller branches which whipped him as they tore along. He wore nothing on his head but a leather skull cap, his copper helmet being kept in one of the saddlebags. He kept one hand raised to guard his face and mentally flogged the morse again. The big beast responded with increased speed and also rising irritation, which Hiero felt as a wave of mental heat.

Sorry, I’ll let you do your own job, he sent, and tried to relax. No one was exactly sure just how intelligent a morse really was. Bred from the mutated giant moose many generations before, although well after The Death, they were marvelous draft and riding animals. The Abbeys protected their herds carefully and sold their prized breeding stock with great reluctance. But there was a stubborn core of independence which no one had been able to breed out, and allied to it an uncertain but high degree of intelligence. The Abbey psykes were still testing their morses and would continue to do so.

Hiero swore suddenly and slapped at his forehead. The mosquitoes and black flies were attacking, and the splash of water below indicated Klootz was aiming for a swamp. Behind them the uproar of the herd was growing muted. The buffer did not like swamps, although quite capable of swimming for miles at need.

Hiero did not like swamps either. He signaled ‘halt’ with his legs and body, and Klootz stopped. The bull broke wind explosively. ‘Naughty,’ said Hiero, looking carefully about.

Pools of dark water lay about them. Just ahead, the water broadened into a still pond of considerable size. They had stopped on an island of rock, liberally piled with broken logs, no doubt by the past season’s flood waters. It was very silent here, with the roar and grumble of the buffer only a distant background noise now, behind them and to the east. A small, dark bird ran down a lichened tree trunk and twittered faintly. Dark pines and pale cypress rose directly from the water, cutting off sunlight and giving the place a gloomy aspect. The flies and mosquitoes were bad, their humming attack causing Hiero to pull up the hood of his jacket. The morse stamped and blew out his great lips in a snort.

The ripple on the black surface was what saved them. Hiero was too well trained to abandon all caution, even when slapping bugs, and the oily ‘V’ of something moving just under the surface toward the island from farther out in the open water caught his eye as he looked about.

‘Come on up,’ he shouted, and reined the big beast back on its haunches, so that they were at least ten feet from the edge when the snapper emerged.

There was no question of fighting. Even the bolstered thrower at Hiero’s side, and certainly his spear and knife, were almost useless against a full-grown snapper. Nor did Klootz feel any differently, in spite of all his bulk and fighting ability.

The snapper’s hideous beaked head was four feet long and three wide. The giant turtle squattered out of the water in one explosive rush, clawed feet scrabbling for a hold on the rock, the high, grey, serrated shell spraying foul water as it came, yellow eyes gleaming. Overall, it must have weighed over three tons, but it moved very fast just the same. From a sixty-five-pound maximum weight before The Death, the snappers had grown heroically, and they made many bodies of water impassable except by an army. Even the Dam People had to take precautions.

Still, fast as it was, it was no match for the frightened morse. The big animal could turn on half his own length and now did so. Even as the snapper’s beaked gape appeared over the little islet’s peak, the morse and his rider were a hundred feet off and going strong through the shallow marsh, back the way they had come, spraying water in sheets. Stupid as it was, the snapper could see no point in following further, and shut its hooked jaws with a reluctant snap as the galloping figure of the morse disappeared around the pile of windfalls.

As soon as they had reached dry ground, Hiero reined in the morse and both listened again. The roar of the buffer’s passage was steadily dying away to the south and east. Since this was the direction he wanted to go anyway, Hiero urged Klootz forward on the track of the migrating herd. Once more both man and beast were relaxed, without losing any watchfulness in the process. In the Year of Our Lord, seven thousand, four hundred, and seventy-six, constant vigilance paid off.

Moving cautiously, since he did not wish to come upon a buffer cow with a calf or an old outcast bull lagging behind the herd, Hiero steered the morse slowly back to the road he had left earlier. There were no buffer in sight, but a haze hung on the windless air, fine dust kicked up by hundreds of hoofed feet and piles of steaming dung lay everywhere. The stable reek of the herd blanked out all other scents, something that made both man and morse uncomfortable, for they relied on their excellent noses, as well as eyes and ears.

Hiero decided, nonetheless, to follow the herd. It was not a large one, he estimated, no more than two thousand head at most, and in its immediate wake lay a considerable amount of safety from the various dangers of the Taig. There were perils too, of course, there were perils everywhere, but a wise man tried to balance the lesser against the greater. Among the lesser were the commensal vermin, which followed a buffer herd, preying on the injured, the aged, and the juveniles. As Hiero urged the morse forward, a pair of big, grey wolves loped across the track ahead of them, snarling as they did. Wolves had not changed much, despite the vast changes around them and the mutated life of the world in general. Certain creatures and plants seemed to reject spontaneous genetic alteration, and wolves, whose plasticity of gene had enabled thousands of dog breeds to appear in the ancient world, had reverted to type and stayed there. They were cleverer, though, and avoided confrontation with humans if possible. Also, they killed any domestic dog they could find, patiently stalking it if necessary, so that the people of the Taig kept their dogs close at hand and shut them up at night.

Hiero, being an Exorcist and thus a scientist, knew this of course, and also knew the wolves would give him no trouble if he gave them none. He could ‘hear’ their defiance in his mind and so could his huge mount, but both could also assess the danger involved, which was almost non-existent in this case.

Reverting to his leaf-snatching amble, the morse followed the track of the herd, which in turn was roughly following the road. Two cartloads wide, this particular dirt road was hardly an important artery of commerce between the East of Kanda and the West, out of which Hiero was now riding. The Metz Republic, which claimed him as a citizen, was a sprawling area of indefinite boundaries, roughly comprising ancient Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta, as well as parts of the old Northwest Territories. There were so few people in comparison to the land area that territorial boundaries were somewhat meaningless in the old sense of the word. They tended to be ethnic or even religious, rather than national.

The Taig, the vast boreal forest of conifers which had spread across the northern world at least a million years before The Death, still dominated the North. It was changed, however, with many species of warm country plants intermingled with the great pines. Some plant species had died, vanished entirely, as had some animals also, but most had survived, and adapted to the warmer climate. Winters were now fairly mild in the West of Kanda, with the temperature seldom ever getting below five degrees centigrade. The polar caps had shrunk and the earth was once again in another deep interglacial period. What had caused the change to be so drastic, man or nature, was a debated point in the Abbey classrooms. The Greenhouse Effect and its results were still preserved in the old records, but too much empiric data was lacking to be certain. Scientists, both Abbey and laymen, however, never stopped searching for more data on the lost ages in an effort to help shape the future. The terror of the ancient past was one thing which had never been lost, despite almost five thousand years. That The Death must never be allowed to come again was the basic reason for all scientific training. On this, except for outlaws and the Unclean, all men were agreed. As a good scientist and Abbey scholar, Hiero continually reflected on the problems of the past, even as now, while seeming to daydream in the saddle.

He made an effective picture as he slowly rode along, and not being without vanity, was aware of it. He was a stocky young man, clean-shaven but for a mustache, with the straight black hair, copper skin and hooked nose of a good Metz. He was moderately proud of his pure descent, for he could tell of thirty generations of his family without a break. It had come as a profound shock in the Abbey school, when the Father Abbot had gently pointed out that he and all other true Metz, including the abbot himself, were descended from the Metis, The French-Canadian-Indian half-breeds of the remote past, a poverty-stricken minority whose remoteness and isolation from city life had helped save a disproportionate number of them from The Death. Once this had been made clear to him, Hiero and his classmates never again boasted of their birth. The egalitarian rule of the Abbeys, based solely on merit, became a new source of pride instead.

On Hiero’s back was strapped his great knife, a thing like a short, massive sword, with a straight, heavy back, a sharp point, a fourteen-inch rounded blade, and only one edge. It was very old, this object from before The Death, and a prize won by Hiero for scholastic excellence. On its blade were incised in worn letters and numbers, ‘U.S.’ and ‘1917’ and ‘Plumb. Phila.,’ with a picture of a thing like an onion with leaves attached. Hiero knew it was incredibly ancient and that it had once belonged to men of the United States, which had long ago been a great empire of the South. This was all he or perhaps anyone could know of the old Marine Corps bolo, made for a long-lost campaign in Central America, forgotten five millennia and more. But it was a good weapon and he loved its weight.

He also carried a short, heavy spear, a weapon with a hickory shaft and ten-inch, leaf-shaped, steel blade. A crossbar of steel went through the base of the blade at right angles, creating what any ancient student of weaponry would have recognized at once as a boar spear. The cross guard was designed to prevent any animal (or human) from forcing its way up the spear shaft even when impaled by the spear’s point. This was not an old weapon, but had been made by the Abbey armory for Hiero when he had completed his Man Tests. At his saddlebow was holstered a third weapon, wooden stock forward. This was a Thrower, a muzzleloading, smoothbore carbine, whose inch and a half bore fired six-inch-long explosive rockets. The weapon was hideously expensive, the barrel being made of beryllium copper, and its small projectiles had to be hand-loaded by the small, private factory which produced them. It was a graduation present from his father, and had cost twenty robes of prime marten fur. When his stock of projectiles was exhausted, the thrower was useless, but he carried fifty of them in his pack and few creatures alive could take a rocket shell and still keep coming. A six-inch, two-edged knife, bone-handled, hung in his belt scabbard.

His clothes were leather, beautifully dressed tan deer-skin, very close-fitting, almost as soft as cloth and far more durable. In his leather saddlebags were packed a fur jacket, gloves and folding snow shoes, as well as food, some small pieces of copper and silver for trading, and his Exorcist’s gear. On his feet were knee boots of brown deerskin, with triple strength heels and soles of hardened, layered leather for walking. The circled cross and sword of the Abbeys gleamed in silver on his breast, a heavy thong supporting the medallion. And on his bronzed, square face were painted the marks of his rank in the Abbey service, a yellow maple leaf on the forehead and under it, two snakes coiled about a spear shaft, done in green. These marks were very ancient indeed and were always put on first by the head of the Abbey, the Father Superior himself when the rank was first achieved. Each morning, Hiero renewed them from tiny jars carried in his saddlebags. Throughout the entire north, they were recognized and honored, except by those humans beyond the law and the unnatural creatures spawned by The Death, the Leemutes*, who were mankind’s greatest enemy.

Hiero was thirty-six and unmarried, although most men his age were the heads of large families. Yet he did not want to become abbot or other member of the hierarchy and end up as an administrator, he was sure of that. When teased about it, he was apt to remark, with an immobile face, that no woman, or women, could interest him for long enough to perform the ceremony. But he was no celibate. The celibate priesthood was a thing of the dead past. Priests were expected to be part of the world, to struggle, to work, to share in all worldly activities, and there was nothing worldlier than sex. The Abbeys were not even sure if Rome, the ancient legendary seat of their faith, still existed, somewhere far over the Eastern Ocean. But even if it did, their long-lost traditional obedience to its Pontiff was gone forever, gone with the knowledge of how to communicate across so vast a distance and many other things as well.

Birds sang in massed choruses as Hiero rode along in the afternoon sunlight. The sky was cloudless and the August heat not uncomfortable. The morse ambled at exactly the pace he had learned brought no goad and not one instant faster. Klootz was fond of his master and knew exactly how far Hiero could be pushed before he lost his patience. The bull’s great ears fanned the air in ceaseless search for news, recording the movements of small creatures as much as a quarter of a mile away in the wood. But before the long, drooping muzzle of the steed and the rider’s abstracted eye, the dusty road lay empty, spotted with fresh dung and churned up by the buffer herd, whose passage could still be heard ahead of them in the distance.

This was virgin timber through which the road ran. Much of the Kandan continent was unsettled, much more utterly unknown. Settlements tended to radiate from one of the great Abbeys, for adventurous souls had a habit of disappearing. The pioneer settlements which were unplanned and owed their existence to an uncontrolled desire for new land had a habit of mysteriously falling out of communication. Then, one day, some woodsman, or perhaps a priest sent by the nearest Abbey, would find a cluster of moldering houses surrounded by overgrown fields. There was occasional muttering that the Abbeys discouraged settlers and tried to prevent new opening up of the woods, but no one ever dreamed that the priesthood was in any way responsible for the vanished people. The Council of Abbots had repeatedly warned against careless pioneering into unknown areas, but, beyond the very inner disciplines taught to the priesthood, the Abbeys had few secrets and never interfered in everyday affairs. They tried to build new Abbeys as fast as possible, thus creating new enclaves of civilization around which settlements could rally, but there were only so many people in the world, and few of these made either good priests or soldiers. It was slow work.

As Hiero rode, his mnemonic training helped him automatically to catalogue for future reference everything he saw. The towering jackpines, the great white-barked aspens, the olive palmetto heads, a glimpse of giant grouse through the trees, all were of interest to the Abbey files. A priest learned early that exact knowledge was the only real weapon against a savage and uncertain world.

Morse and rider were now eight days beyond the easternmost Abbey of the Metz Republic, and this particular road ran far to the south of the main east–west artery to distant Otwah, and was little known. Hiero had picked it after careful thought, because he was going both south and east himself, and also because using it would supply new data for the Abbey research centers.

His thoughts reverted to his mission. He was only one of the six Abbey volunteers. He had no illusions about the dangers involved in what he was doing. The world was full of savage beasts and more savage men, those who lived beyond any law and made pacts with darkness and the Leemutes. And the Leemutes themselves, what of them? Twice he had fought for his life against them, the last time two years back. A pack of fifty hideous apelike creatures, hitherto unknown, riding bareback on giant, brindled dog-things, had attacked a convoy on the great western highway while he had commanded the guard. Despite all his fore-looking and alertness, and the fact that he had a hundred trained Abbeyman, as well as the armed traders, all good fighters, the attack had been beaten off only with great difficulty. Twenty dead men and several cartloads of vanished goods were the result. And not one captive, dead or alive. If a Leemute fell, one of the great spotted dog-things had seized him and borne him away.

Hiero had studied the Leemute files for years and knew as much as anyone below the rank of abbot about the various kinds. And he knew enough to know how much he did not know, that many things existed in the wide world of which he was totally ignorant.

The thought of fore-looking made Hiero rein the morse to a halt. Using the mind powers, with or without Lucinoge, could be very dangerous. The Unclean often had great mental powers too, and some of them were alerted by human thoughts, alerted and drawn to them. There was no question of what would happen if a pack such as had struck the convoy found a lone man ready to hand.

Still, there had to be some danger anywhere, and fore-looking often helped one to avoid it if not used to excess. ‘Your wits, your training, and your senses are your best guides,’ the father abbots taught. ‘Mental search, fore-looking, and cold-scanning are no replacements for these. And if overused, they are very dangerous.’ That was plain enough. But Hiero Desteen was no helpless youth, but a veteran priest-officer, and all this by now was so much reflex action.

He urged the morse off the track, as he did so hearing the buffer herd just at the very edge of earshot. They are travelling fast, he thought, and wondered why.

In a little sunny glade, a hundred yards from the trail, he dismounted and ordered Klootz to stand watch. The big morse knew the routine as well as the man and lifted his ungainly head and shook the still-soft rack of antlers. From the left saddlebag, Hiero took his priest’s case and removed the board, its pieces, then the crystal and the stole; draping the latter over his shoulders, he seated himself cross-legged on the pine needles and stared into the crystal. At the same time he positioned his left hand on the board, lightly but firmly over the pile of markers and with his right made the sign of the cross on his forehead and breast.

‘In the name of the Father, his murdered Son and Spirit,’ he intoned, ‘I, a pri

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...