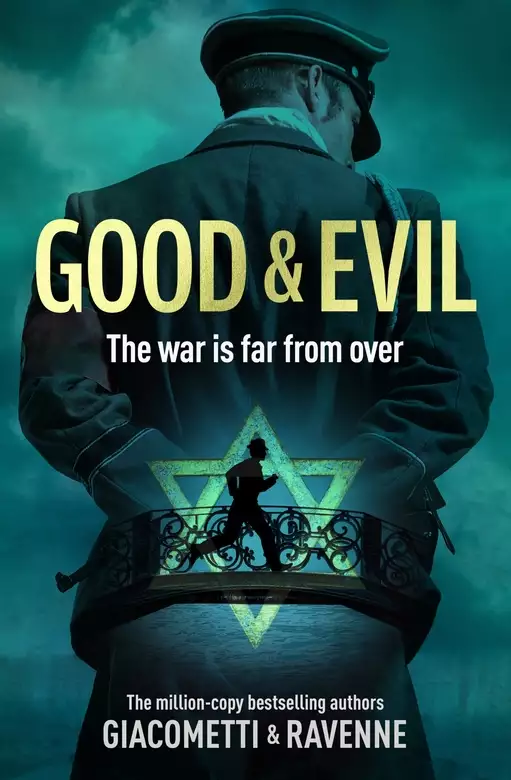

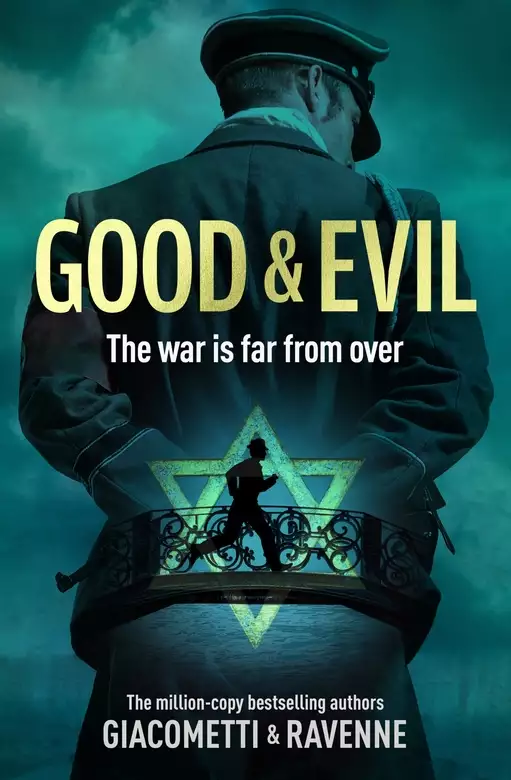

Good & Evil

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

OUT NOW: the second volume in the bestselling, exhilarating WWII treasure-hunt thriller series for fans of Dan Brown

*** RATED 5 STARS BY REAL READERS ***

*** PREORDER BOOK 3, HELLBOUND, NOW: https://amz.run/3tyk ***

November 1941. Germany is about to win the war. Only one thing still separates the Nazis from a certain victory: they must find the three remaining all-powerful swastikas and reunite them with a fourth that is safely hidden away in Himmler''s mountain stronghold.

Churchill has no choice but to mobilize his best man, double agent Tristan Marcas, and employ the most risky techniques to beat them to it. It all comes to a showdown at a ball in Venice...

Release date: September 17, 2020

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Good & Evil

They didn’t know when, or who, but after centuries of waiting, they know the day has come.

Or rather, the night.

A bloody night.

The five farmers slink silently between the olive trees. In the darkness, olive trees look much like people. They are a similar size and a comparable shape, and even if a tree has been bent or broken by the wind, it can still hide a man.

A man must listen. He must listen to the shadows that never fall silent. They whisper to those who listen for them. The same word, again and again:

Xeni!

Xeni!

Xeni!

Invaders.

Warriors from the North, their heads protected by steel helmets, have come to sully their lands and steal the sacred treasure a stranger entrusted to the villagers. A stranger from an ancient boreal nation.

The five farmers are certain that the blond men strutting before their eyes are the barbarians described in the prophecy.

A gentle, fragrant breeze rustles the olive leaves, like a peaceful ancestral melody corrupted by the invaders’ presence.

They may not have a name, but the parasites have a sound: the thumping of boots on the earth, of guns jostling in their holsters,the din of imminent war and death. But sometimes death takes another path.

Though still hidden behind the olive trees, the farmers have moved. They need to see now, to know how many invaders there are.

One, two, three.

They see the barrels of the rifles propped up against the wall, the spark of a lighter, and the tiny sizzling circles of cigarettes. They watch as the soldiers become men again. Just in time to die.

The five farmers have been trained to deliver death to anyone who dares defy the rules. Like their fathers before them, and their fathers’ fathers.

They are not just farmers, they are Fylaques. Guardians.

All of divine blood. They were born in Crete, the island of honey, the place chosen by Zeus’s mother to give birth to the father of the gods.

Fylaques are trained to handle the kyro, a dangerous dagger engraved with a red drop of blood, better than any other Cretan. The weapon thirsts for the last ounce of blood in the enemy’s body.

From behind the olive trees, the five Fylaques smile as they watch the warriors from the North. The first enemy has just unbuckled his belt and removed his jacket. The heat is stifling. He’s not used to it. He and his companions are the children of a cold climate, as cold as their hearts.

Their bodies are pale.

But not for long.

One of the Fylaques steps out of the shadows. He unfolds his kyro, the perfectly oiled spring freeing the blade from the horn handle. The metal is coated in charcoal to prevent it from glinting in the light. The others join him, baring their teeth as they prepare to strike.

The invaders have their backs to them. They’re working around the well and won’t hear a thing. Their ears are focused on the clanging of the bucket against the walls as they retrieve it. They’ve been thirsty all day and the only thing they can hear is their own cries for water.

They’ve forgotten they are invaders.

The promise of water drowns out all other sounds.

The first Fylaque emerges further from the darkness.

The head of the pack.

He stands silently, waits for the clang of the bucket against the rim of the well, and attacks.

The kyro is so sharp that it slips effortlessly between the enemy’s ribs. The pain is so intense that the foreigner doesn’t even cry out. He looks up at the stars as if he’s never seen them before, then darkness veils his eyes, and he falls silently to the ground. The rest of the soldiers have plunged their hands and mouths into the water. They are deaf to their fate. The blades slide deep into their necks. The last thing they’ll notice is the strange taste of the water—the tang of their own blood.

The foreigners are just bodies now. Bodies the Fylaques place around the well in a star shape. They cross themselves, not to ask for forgiveness for what they have done, but for what they are about to do. They turn the corpses over onto their backs.

Each kyro pauses just above the victim’s sternum, then cuts through the skin, which parts like moist lips.

They plunge their hands inside. Rifle around.

When they stand back up, a bittersweet smell rises from the ground.

Thanatos.

To truly kill an enemy, you must take more than his life.

The horizon disappeared into a lead-coloured sky. A curtain of rain pounded into the silver sea. The Admiralty’s forecast was accurate—bad weather always blew in from the southwest. From France. It was only three o’clock in the afternoon, but the harbour master’s office had already turned on the safety beacons. The wind was still a breeze, but it would pick up soon.

The port in Southampton—the second largest in the southern part of the country, after Portsmouth—was bustling. Swarms of ships of many different sizes moved in and out of the main docks. Since war had broken out, cargo ships and naval destroyers had replaced the legendary transatlantic cruise ships and luxury yachts. The Titanic was but a distant memory. No one embarked on holiday from Southampton anymore—now they went to war.

From the bridge of the Cornwallis, Captain Killdare watched the cranes dance over the main deck. It was taking forever to load the last crates. The ship should have got underway hours ago. Killdare wanted to leave the estuary as quickly as possible and get past the Isle of Wight, to avoid a possible Luftwaffe raid. Though the bombings had died down since the end of May—Britain had won the battle for the skies, thanks to its Spitfire squadrons—the Germans didn’t let them forget that they were at war, and regularly launched attacks on British military or civilian targets. Southampton and Portsmouth still received their fair share of fire and shrapnel. Stuck at port, the Cornwallis was easy prey for Göring’s vultures.

Annoyed by the delay, Killdare picked up the receiver and called the officer in charge of the hold.

“Jesus, Matthews, what are your dockers doing? Do you want to keep us here all night?”

“Just one more crate and we’re done, Captain. The actuator on one of the cranes got stuck because of that damn synthetic oil.”

“Of course, the oil. Why not blame it on Nazi sabotage, while we’re at it? If you want my opinion, the dockers are just taking it easy. War or no war, it’s all the same to them.”

Captain Killdare hung up, even more irked than before. He’d been in a bad mood for a whole week, ever since his meeting at the shipowner’s head office. To his great surprise, the manager of maritime operations for the Cunard Line had asked him to captain the Cornwallis, a lightweight cruise ship headed for New York.

A cruise ship! Killdare couldn’t stand them.

His speciality had always been cargo vessels. He enjoyed an excellent reputation for getting his merchandise—whatever its worth—safely to its destination anywhere in the world. Shipowners had been vying to hire him since he’d rescued a sinking cargo off the coast of Macao, despite half of his crew having jumped ship.

And now they wanted him to captain the Cornwallis. It wasn’t even a Class A vessel, like the Queen Mary. The Cornwallis was to transport industrial equipment to the United States as part of a new strategy implemented by the General Staff. An officer from the Atlantic fleet had explained their reasoning: “The German U-boats hunt in packs across the Atlantic, and only go after military convoys and big cargo ships. Their torpedoes are too precious to waste on civilian transport vessels.”

The door to the bridge creaked open as a tall man in a stylish camel-coloured raincoat came in. He held his soft felt hat in his hand. Killdare shot him an angry look.

“Hello, Captain. I’m John Brown,” the intruder explained calmly. “Lovely to meet you.”

The sailor stared suspiciously at Mr. Brown. He’d been warned of his arrival. A bigwig, according to the Cunard management office. The man was in his fifties, with a thin, pale face—a typical London bureaucrat, from a ministry or a bank. His name was clearly an alias. It all reeked of trouble. The captain mumbled hello and shook his hand, which was firmer than he’d expected.

“What can I do for you?” asked Killdare in the most dismissive tone he could muster.

“When do you plan to leave?”

“In half an hour or less, I’d say.”

“Perfect. One of my subordinates will be on board for this crossing. Please do your best to ensure he’s comfortable.”

The captain shrugged. “You mean the rude, bearded fellow who smells of tobacco and is inseparable from his metal case? The bloke in cabin 35B? He’ll be as comfortable as any other passenger on the upper deck. No more, no less. Now, if you don’t mind, I have a ship to ready for departure. I’ll pass on your recommendations to my second-in-command. Good day.”

The captain turned around, terminating the conversation, and began inspecting the pressure gauges on the instrument panel. A few seconds passed, but Mr. Brown didn’t budge.

“Captain, I don’t think you understand.”

Killdare turned his head, and saw a military card bearing Mr. Brown’s photo. Commander James Malorley, Army Strategic Division.

“You see, that rude, bearded fellow is my deputy. He’s on a confidential mission of the utmost importance to the British government, so it would be best for you to make things as easy as possible for him during his stay. Please note that I’m using the conditional only to be polite.”

Killdare stood up straight. He’d served four years in the Royal Navy and instinctively grew an inch when confronted with high-ranking officers.

“I apologize, Commander. You should have introduced yourself sooner. I’m a little anxious, with all these Kraut raids. The sooner I’m out of here, the better.”

“A network of German spies was uncovered in Portsmouth last week, so I’m wary of lingering ears. I have a letter for you.”

Commander Malorley handed him a yellow envelope bearing the Prime Minister’s seal. “These are your instructions. Open them when you’re at sea. You’ll notice that they come directly from the highest authority. Read them carefully. Captain Andrew—the rude bloke, as you call him—will come and explain what it’s all about.”

“If the mission is so important, isn’t it dangerous to get civilians mixed up in it? I have thirty passengers on board. I know we’re at war, but using innocent people as a cover isn’t very … sportsmanlike.”

“Do you think Hitler and his friends are sportsmanlike? It’s an honourable sentiment, but don’t worry about the passengers; they’re all professionals who know the risks. Moreover, you’ll be escorted by two submarines for the entire crossing. They’ll be perfectly discreet, of course, and will join you just outside the port.”

A siren sounded twice in the bridge, signalling that the ship was fully loaded.

“I see it’s time to go. Good luck,” said the commander, staring hard at the captain. “If I told you the outcome of the war is in your hands, would you believe me?”

“Given the look of your deputy, I’d bet you a-hundred-to-one. But anything is possible these days, like talking to a military commander who goes by the name of Mr. Brown, or watching Europe march to the orders of a chap with a Charlie Chaplin moustache. I’ll get your precious cargo to its destination, even if I have to cross the Sargasso Sea and confront Neptune himself.”

The commander gave the captain a firm pat on the shoulder and left the bridge, tightly buttoning up his raincoat. The temperature had dropped several degrees and the damp found its way into his shirt collar.

As he set foot on the wet wharf, the Cornwallis’s siren wailed across the dock. Harbour employees in mustard-coloured overalls untied the mooring lines and threw them to the sailors swarming on the deck.

Commander James Malorley of the Special Operations Executive, aka Mr. Brown, watched the ship’s black stern move slowly away from the dock. How curious that the ship chosen to carry the sacred swastika—the first of four such relics; three others were yet to be retrieved by the Allies—bore the name of the head of the British army during the American Revolution, Lord Cornwallis, George Washington’s arch-enemy.

The stench of fuel oil filled the air as the vessel spun around to face the harbour’s exit. Deep within the hull, machinery whirred softly.

Malorley glanced one last time at the ship, pulled his felt hat down, and turned towards the harbour master’s office, where Laure d’Estillac was waiting for him inside the Amilcar.

He didn’t want to admit it, but he was relieved to see the swastika leave for the other side of the Atlantic, thousands of miles away. He and his SOE colleagues had risked their lives to keep it from the Nazis, and many lives had been claimed. Jane’s face surfaced in his mind. He could still see the surprised, almost childlike expression on the young agent’s face as she was brought down by a hail of German bullets. Her blonde hair shone brightly in the enemy searchlights. She had fallen far away, in southern France, near the Pyrenees. In Cathar country in a field at Montségur, at the exact place where the heretics had been burned alive centuries earlier. Unable to save her, he had fled like a coward to keep the relic safe.

Malorley could still feel the kiss she’d given him as they fled the castle. A long kiss, as if the brave young woman had known it would be their last.

Big drops of rain soaked the dock. The commander shivered and tightened the scarf around his neck.

The shower dripped down from his hat, blurring Jane’s face, leaving him lost in his thoughts. He was a solitary man who’d given up on a normal life. No wife, no children, not even a dog. He lived to do his duty. Not by choice—fate had decided for him by involving him in the quest for the relics. Malorley knew he was a piece on a chess board, and the game’s stakes were unclear. A game of chess that had been going on for thousands of years. He had no idea whether he was a pawn or a king, but he was sure that others before him, people from other times and civilizations, had lost their lives and souls to this adventure.

He hastened his step, so as not to be soaked by the time he reached the car on the other side of the dock.

Suddenly, a strident siren rang out over the port. Malorley’s blood began rushing through his veins as the muscles in his legs leapt into action. Since the beginning of the war, the reflex had become an instinct, as it had for most British people. Malorley ran along the dock as fast as he could. He only had a few minutes left. This wasn’t a ship siren; it was the anti-aircraft defence system. It meant the German eagle was on the hunt. And its cruel presence promised blood, fire, and death.

Karl woke up screaming. He immediately groped for the gun he’d left next to his bed. When he felt the grip against his palm, his pulse began to slow. It put a stop to the unbearable buzzing that filled his ears each time he woke in the middle of the night, his mouth dry and breathing shallow. Fear. Crete was the first place he’d ever truly experienced the indescribable sensation. The fear of death, of the night, of the unknown. He didn’t even really know what he feared most anymore. He’d spent most of his life handling shovels and brushes at archaeological excavations, but now the only thing that made him feel better was the gun in his hand. And he was so thirsty. All the time. It was autumn, but the heat was still stifling in Crete. Especially at night. And he was one of the lucky ones—he was staying in a real house that had been requisitioned on the island. For the soldiers, who were staying in tents, sleep was but a distant memory, and it showed in their work.

Karl had alerted Berlin several times, asking for reinforcements, particularly since the excavation site just kept growing. But his boss, Colonel Weistort, had been seriously injured on a mission. And no one in Germany seemed to be interested in Crete anymore. All eyes had been focused on the eastern front since millions of German soldiers had set off to conquer Russia. An indomitable wave was about to crash into Moscow.

Karl Häsner stood up, shaking his head. He wasn’t interested in politics, much less war. As for the Nazis, if he was honest, he despised them. He was an intellectual, nothing like those fanatics shouting in stadiums, the SS officers clicking their heels in their black uniforms, or that moustached dwarf with his damn tirades. How had Germany fallen into his hands? Karl plunged his head into the lukewarm water in the sink as if he were trying to wash something away. In fact, he was cheating fate. Thousands of young German men were dying on the eastern front while he delicately handled a brush to reveal the surface of an amphora. Instead of joining the army, he had used his degrees to find a place at Himmler’s research institute, the Ahnenerbe. Better to be an archaeologist for the regime than a corpse out on parole.

Karl began to shake.

He had thought he was escaping death, but this was far worse.

Luckily, work helped soothe his anxiety. Upstairs, the former owner had set up a library with windows as narrow as dungeon arrow slits. It must have been designed to keep out the freezing winter wind and scorching summer sun. For Karl, the room had become a sanctuary. He felt safe as soon as he walked in. The walls covered in books and chests full of artefacts made him feel like he was in a world free of violence and danger. He knew it was an illusion, but he clung to it with all his strength, even if he did keep his gun within arm’s reach. Across from the door, stood a long wooden table where Karl gathered the most precious finds from the site.

The Ahnenerbe archaeologists had arrived in Knossos in June, when the German parachutists hadn’t yet subdued the entire island, despite ferocious battles. The team had got to work immediately. Himmler was obsessed with the legend of the Minotaur and the labyrinth and was determined to find traces of them. Much to Karl’s surprise, he was not at all interested in any other Greek archaeological treasures. He wanted specific results, and he wanted them quickly. In just a few weeks, they had made some exceptional discoveries. The rarest pieces were still in the room. He should have sent them to Berlin, but he couldn’t bear to part with them. In a world at war, the fragments of frescoes depicting teenagers swimming with dolphins and statues of goddesses with marble breasts, their wrists wrapped in snakes—all this still, serene beauty—had become absolutely necessary to his survival.

An object was waiting for him on the table. The oval shape featured a delicately carved border. It reminded him of a compact mirror, except that it was made entirely of gold. It was the first artefact made of precious metal that the team had found. They’d uncovered it near a corner of a brick wall, on a bed of ashes, where it seemed to have been purposefully left rather than lost or thrown away. Like an offering. Karl studied the object as it glinted in the light. How long had it been buried? Centuries, undoubtedly, and yet it shone as if it had just left the goldsmith’s shop. Karl noticed a carefully drilled hole on the upper edge, probably for a chain. Was it a piece of jewellery a woman had removed from around her neck as tribute for the gods, or a religious relic only worn during sacred ceremonies? Karl sighed. The feeling of oppression that had been with him since waking was beginning to dissipate. Beauty always vanquished fear. Nevertheless, something worried him. The surface of the object wasn’t smooth. The goldsmith had engraved it with a symbol. A symbol that was omnipresent in his life.

A swastika.

Karl studied it, fascinated. He resisted the urge to run his finger over it, as if he were afraid of being contaminated by its dark and ancient power. Ridiculous! Häsner shook his head. He was an archaeologist, not a medium. His job was to analyze and interpret, not to explore mad theories. He was still thirsty. He knew he should go down to the kitchen and get a drink, then try to go back to sleep. He knew he shouldn’t work so late at night anymore, or he’d start seeing things. And yet, he stayed put, his eyes fixed on the symbol that left him uneasy. Why had a man from thousands of years ago decided to so carefully engrave the object with this symbol? What did it mean? What was it worth? And most importantly, how had this symbol travelled through time to appear in Germany, where it figured at the centre of every flag? That was the real question. Karl had a bad feeling about all of it. A foreboding suspicion that this symbol, forgotten for centuries, hadn’t come back for no reason. During its long absence, it had absorbed energy and power, and now it was ready to act.

Karl brought his hand to his forehead. He must be feverish. It was the only explanation. How could he have such irrational ideas? He roughly placed the object back on the table, as if to break a spell. Tomorrow he would send it to Berlin. Himmler would be delighted. The smallest swastika left him jubilant. As for Karl, he was done with these ridiculous ideas and irrational fears. For good.

A fist banged on the front door and the sound echoed upstairs.

“Herr Häsner!”

Karl hurried to the window. Through the narrow opening, he saw two soldiers lit by torchlight. Their uniforms were dishevelled and they both held their guns at the ready. Karl returned to the table and carefully placed the artefact in a numbered box, which he slid into a drawer. He locked it inside. Each of his movements was excessively meticulous. Though he didn’t dare admit it, he was putting off the inescapable moment when he would have to turn around. What if he wasn’t alone in the library? What if there was a shadow between him and the stairs?

“Herr Häsner! Open up! Hurry!”

The wooden door resonated like a drum. He had no choice. He turned around suddenly. The room was empty. He crossed it in three steps, ran down the stairs, and rushed to the entryway. He turned the key in the lock. Two soldiers appeared, their faces filled with terror.

“It happened again!”

The village was not far from the excavation site. Narrow streets full of one-storey houses were dominated by the blue dome of the church. The soldiers stationed there had set up a searchlight to reach even the darkest corners. A wandering dog, startled by the blinding beam, disappeared into an alley. All the town’s residents had holed up in their homes, shutters closed tight. The priest was the only one to be seen, kneeling in prayer before a wrinkled canvas. Karl stopped short. The officer on duty came over and grabbed his arm to pull him aside, without so much as a salute.

“Three more!”

“Is this where you found them?”

“No, on the outskirts of town. They were fetching water.”

“In the middle of the night?”

“The area is teeming with rebels. We’re afraid they’re poisoning public wells. So, we go to hidden sources. And never to the same one twice.”

Häsner ran his hand over his forehead. He was burning up. To keep the soldier from noticing his dizzy spell, he pointed towards the canvas, hoping his hand wouldn’t shake.

“Why didn’t you leave them where you found them? There may have been clues, proof …”

“The proof is right here! The entire population is complicit. They feed information to the resistance. And this time, they will pay! Dearly!”

Karl imagined the wave of repression that would hit the village. His mission would be definitively compromised.

“How did you find your men?”

The officer, a captain, took a step back.

“It was the dogs. They’re starving in this damn place. They must have smelled the blood. They wouldn’t stop barking, so a patrol went to have a look.”

“I see. Show me.”

A guard tapped the priest with the butt of his rifle to get him to move aside. The searchlight shone on the dirty canvas as a soldier pulled it back and turned his head away.

At first, Karl didn’t understand. The bodies looked like they had been trampled, hammered, and ripped apart in every direction. He moved closer. Meat. It was already rotting. He couldn’t distinguish anything. No joints, no organs. Everything was red, in ragged pieces. Despite his revulsion, Karl bent over. The skull of one of the corpses was broken in several places. Bone fragments had slid down to the face. Karl gestured to the officer to come nearer.

“What happened here?”

The captain cleared his throat.

“When we got there, the dogs had gone crazy, Herr Häsner. We couldn’t retrieve the bodies. So, we had to fire our guns, first into the air, then …”

Karl felt around in vain for something to steady himself. “… Into the bodies. Transfer them to the military doctor for autopsy. If it’s even possible.”

The village looked like it was under siege. Every street that led out of town was blocked by a squad of soldiers. Mobile teams kept watch over the houses along the olive orchards. Headlights shone on every home, with the searchlight in the town square focusing on the houses of the village’s most notable residents.

“The site is locked down, Captain.”

The officer nodded. Now the show could begin.

“What are you going to do?” asked Karl, concerned. “Punish the entire village? We need the locals. How will we find supplies? This excavation is a priority, you know.”

The captain pointed to the skull on his uniform collar.

“I’m SS, and three of my men have just been killed. I’m going to do my own excavations. House by house.”

“You know that if it was resistance fighters, they’re long gone by now. You’ll never find them.”

“Not them, but we can find their loved ones.”

“And do what with them?”

“Take them hostage. A woman and child from each family.”

“You can’t kill civilians!” protested the archaeologist, his emotions getting the better of him.

“We won’t need to. They’ll start talking before long.”

“You think so?”

“Absolutely. Right after I kill the priest, the mayor, and all the members of the local government.”

The field hospital had been set up some distance from the town. It was little more than a group of tents surrounded by barbed wire where a team of doctors and nurses cared for the most recently wounded soldiers, who were awaiting repatriation to Germany. The battles fought by the German parachutists to take control of the island had been remarkably violent, and the cemetery next to the field hospital was full of freshly dug graves. Karl picked up the pace as he caught sight of the many man-sized mounds of earth. He was headed to tent K. That’s where they had taken the bodies of the soldiers killed outside Knossos.

“Herr Häsner?” asked a man in a white jacket, his elbows resting on a wooden pillar as he smoked a cigarette, slowly exhaling pale clouds that unravelled in the darkness. “Come in. The bodies are in the tent.”

In the light of a storm lantern, the three corpses lay on a long table covered in blood.

“We haven’t bothered to clean up around here for a while now,” commented the doctor, as if explaining a local tradition.

“How did they die?” asked the archaeologist, though he realized the question was silly.

The doctor dropped his cigarette on the ground and carefully stubbed it out with his foot.

“Impossible to tell. The bodies have been too damaged.”

Karl cleared his throat. “Before the dogs got to them, they were …”

“Alive, is that what you were going to say? No, they were already dead. If they had been alive, they would have tried to protect their faces. It’s an innate reflex, even if you’re badly wounded. They have no traces of bites on their hands and forearms.”

“Thank God,” Karl murmured.

The doctor shrugged. “Now that you’ve thanked God for letting these poor men be devoured by dogs, why don’t you tell me what you’re doing here. The soldiers are responsible for security issues, not archaeologists, unless I’m mistaken?”

“Yes, but I’m the one who has to report to Reichsführer Himmler. So, it’s either a terrible but relatively straightforward attack by the resistance fighters and I don’t bother him with it, or it’s something else.” Since the doctor remained silent, Karl continued. “Did you notice any unusual lesions, for example?” The doctor put on a pair of gloves and moved towards the bodies. “Or any bullet wounds incompatible with the calibre used by the German army?”

“None of these men were killed by a firearm, I’m sure of it.” He gestured to Häsner to come closer. Each body was a bloody pile of flesh. “Look, right here.”

Karl leaned in towards an indistinct mass of rotting tissue and shredded organs. The only thing he noticed, beyond the unbearable smell, was a hole that was bigger and deeper than the others.

“And the other two bodies have the same wound. If I were you, I would inform Himmler.”

“To tell him what?” asked Karl, annoyed. “That I saw a hole in the middle of a rotting corpse?”

“To tell him someone ripped the livers out of three of his men.”

Laure turned towards the concrete bunker crowned with a bright-red siren. The screeching stopped at the same time as the rain, which

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...