I dream of her still.

It's been years since I've seen her, my oldest friend and truest enemy, but she drifts through my sleep almost nightly. Though her face is usually hidden, my heart recognizes her. "Sookie," I call out, voiceless as if underwater. She turns and all I can see are her teeth gleaming white in the blackness. Her mouth stretches wide, smiling, as if she is happy to see me. But even in my dream, it doesn't seem right, her joy doesn't fit. And then I notice how pointy her teeth are, how they are fangs, really, and how through the slightly open mouth, they are glistening, as if about to take a bite.

When I wake, I try to envision her face, but her features melt into one another; I see a smudge of black hair, dark eyes, a smear of mouth as if through churning waves. Or as if through several layers of photographic negatives: Sookie at eight when we fought Lobetto in the ditch behind her apartment; at fourteen, peeking out from under the paper bag she had put on her head when we went to Dr. Pak's VD clinic; at seventeen when, with her mother's makeup smeared over her face, she taught me about "honeymooning" in the backbooths of the GI clubs; at twenty when she pushed a wet and wailing Myu Myu into my arms and told me, "She's your daughter now." In every memory I have of her, I can hear her words, see her gestures, but her face remains a fragmented blur.

I've written to her-postcards, a line or two on the back of photos of Myu Myu, who wants to be called Maya now. I indulge the child to make up for the beginning of her life, watching her carefully for signs of developmental delays, erratic behavior, eccentricities that could be blamed on me. I am the only mother Maya knows, but for me, in the shadows, there will always be another. These letters are my guilt payment, I suppose, and one day I will send them, these years' worth of notes, to her, care of Club Foxa Hawai'i.

One day, when it is safe, I would like to see Sookie again, once more, face-to-face, so that I can reconcile her in my memory and banish her from my dreams. Maybe after enough time has passed, I could see her clearly, without money or love or other people's vision clouding my eyes.

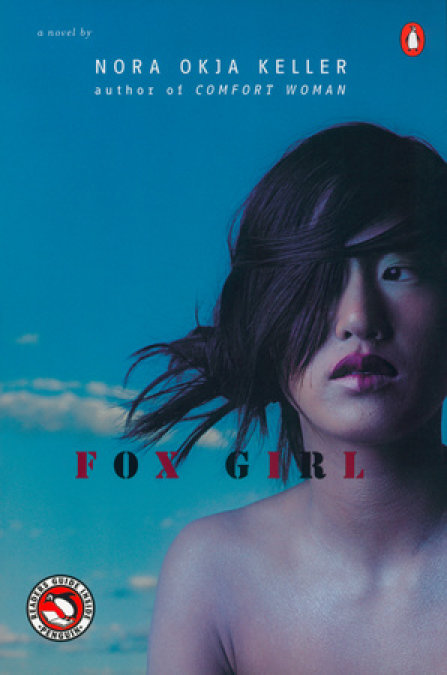

i1

When we were children, everyone in Chollak thought Sookie was ugly; this is what I loved most about her. Her ugliness-bulbous eyed and dark skinned-was greater than mine and shielded me to some degree. "Gundong-hi, ssang-dong-i," the neighborhood boys teased as we walked the path from school. "The Butt Twins," they called us. Sookie covered her ears-bony elbows sticking out like a kite-and I tucked the stained side of my face into my shoulder. Reasoning that they couldn't call me ugly if they didn't see the birthmark, I turned my good side toward the taunting and let the teasing fall on my friend.

"Blackie, black dog," they shouted at her. Sookie, hands still over her ears, would recite the alphabet.

"Your father must be a U.S. darkie!" the boys spat at us. Even Lobetto, whose father was a black GI and whose skin was darker than Sookie's, teased her since at least he had a father.

"Eh, chokka!" I screamed, stooping to pick up a broken piece of concrete from the sidewalk. "I'm gonna kick your penis!"

Young Sik and Chung Woo swiveled their hips and "oooh-ooohed" us. Lobetto yelled back, "I doubt you'd even know where to find it, you pile-of-shit-face! What did your mama do to make you born so ugly? Eh. Hyung Jin?" He pronounced the first part of my name with a hard "g" at the end, changing its meaning from wise truth to scarred truth.

"At least we're pure Korean, not like you, half-half." I jutted out my hip and shook the chunk of concrete at him. Back then, I was the bolder one, secure in my family's station, our relative wealth. I thought we were rich because we never had to worry about rice and once a week we ate meat. Chicken, pork, even beef sometimes.

My mother's family, who had lived in Chollak generations before the start of World War II, owned the sweet shop we worked and lived in. We had an actual house-two rooms with an inside kitchen-not like the piramin shacks that the northerners or the GI girls from America Town lived in. Not like the dump Sookie and her mother had lived in before they found an "uncle" from the base.

"You are pure Korean, hah, Sookie?" I asked under my breath, testing the heft of stone in my palm. I was pretty sure if she wasn't, I would have been forbidden to play with her, just as I had been forbidden to play with Lobetto and Chosopine, before her father had taken her but not her mother to America.

"Ka na da ra!" Sookie continued to sing the alphabet, still holding her hands over her ears. I could see the muscles in her thin arms quivering.

"Hana, dul, set," I growled, and on "three" I whirled and let the concrete fly. Since I never bothered to aim, but threw blindly at the group of boys, I didn't think I'd hit anyone. That day, though, I hit Lobetto in the face, opening a gash across his forehead. "Aaah, good luck!" I cried as I grabbed Sookie's arm to run.

"No, bad luck!" Sookie gasped as the boys, leaving a dazed Lobetto sitting in the middle of the street, swarmed after us. "If Lobetto tells his daddy, my mother will have a hard time getting on the base. Then I might have to be hungry again!"

We cut through the narrow winding alleys toward America Town, jumping over piles of chili peppers laid out on mats to dry, dodging an old halmoni who carried her colicky grandson on her bent back. "Excuse me, Tong Su's Grandma," I called over my shoulder before she began yelling about ill-mannered children racing through the streets like criminals. With luck, the boys would crash into the grandmother and be taken inside to be punished with a lecture and some ear pulling. We bolted into my father's store before Lobetto and his gang turned the corner.

Since our store sat just outside the entrance to America Town, near the point where the GIs divided the streets into white section and black section, we had both pale miguks and dark gomshis stop in to check our merchandise. But our best customers were the kids who liked to come by after school to look at the Juicy Fruit or Coca-Cola, then buy yot or wax lips for something sweet. Only the Americans and their whores could afford the miguk gum and soda.

My father had a big red and white refrigerator especially for the Coca-Cola. When the miguk gave it to us, we tried to put it inside the store, but once it was in, we couldn't open the door and there was no place to put the table of candy. Now the refrigerator sits in front and people call our store Coka, even when all we have in the cooler is kimchee.

The one time the American who installed the cooler came for a maintenance check, he asked my father, "Where Coca-Cola? This only Coca-Cola." He held his fist to his mouth and glug-glugged smacking his lips.

My father pretended not to understand his Korean, pointed to two dusty bottles of Coke we kept on the counter for display, and said, "Three thousand won."

Years later, I understood that the Coca-Cola refrigerator came through Sookie's mother, a gift because of my friendship with Sookie, and because of the promises her mother and my father had made to one another before we were born.

"Appah!" I called out when Sookie and I burst through the door and scuttled under the candy table. I tugged the tablecloth down a few inches, trying to create a shield without tumbling the trays of sweets off the counter. Pulled as far as I dared, the cloth barely covered my face. I scooted toward the shadows against the wall. Sookie squeezed her shoulders between the legs of the stool; with her arms splayed out in front of her and her dark hair hanging in front of her panting face, I thought Lobetto was right: she did look like a black dog.

My father came through the beaded curtain which separated the store from our living space. "What, did I hear my daughter's voice?" he teased, talking to the air above us, pretending not to see us. "Or was that a ghost? A faceless fox spirit that will steal my heart when I sleep?"

"Shh, Daddy," I scolded. "We are hiding from the boys."

Appah laughed. "That is no way to catch a husband, girls. At least let me see what they want." My father strode to the door. When he flung it open, he caught the boys huddled in front, debating whether or not to hunt us in our own territory. "Sirs, come in. Come in."

The boys shuffled in, bare feet tracking in the dust from the streets.

"Would you gentlemen like a piece of yot? Some juice? Mother of Hyun Jin made some fresh plum juice this morning." My father talked to them formally, as if they were paying customers.

Sookie pinched me. "Tell your daddy to throw them out. Tell your daddy to scold them for teasing us. Tell your daddy they called us the Butt Twins," she hissed.

I bit my lip, hating that my father acted so kind to them, yet reluctant to remind him of my ugliness. Wavering, I did nothing.

The boys circled the candy table, kicking under the hem of the tablecloth with probing toes. I scratched at the blackest ones and heard a yelp. Ducking my head to peek out, I saw Young Sik hopping on one foot. I stuck out my tongue at him.

"You decide what you want?" my father asked, stepping in front of the table. I scrambled back, shuffling around his legs for another viewpoint. Pressing my face against the floor, I could crane my head enough to see up the nose of the closest boy.

"Three wax lips," Lobetto grumbled and swatted at a fly circling lazily around the cut above his eye; the blood had gelled so that it was almost the same color and consistency as the cherry-flavored wax lips. Lobetto was the only one with money and had to buy something with my father waiting on him. Swaggering past my father, he thunked his won onto the counter.

Startled, I flinched and pressed closer to Sookie. Above Sookie's breath in my ear, I could hear the boys slurping the juice inside the wax. Imagining them grinning at one another with the fat red wax wedged over their teeth, I rolled my eyes at Sookie. She giggled.

"So, boys." My father clapped his hands over her laughter. "Which one of you has come to propose a match with my daughter?"

One of them choked, spitting his lips onto the floor. The boys stammered, stepping on each other's feet, their bodies bumping together. Lobetto kicked at Young Sik who kicked Chung Woo. Chung Woo bent down to pick up his candy, shooting a look under the table where we crouched. He lifted his real lips toward his nose, like a snarling dog, and narrowed his eyes. Then, slipping the wax lips into his mouth, he flashed us a candied grin before standing.

After the boys left, Appah pulled us out from under the table. "My girl is so popular, the boys follow her home from school." He was joking, but still I preened, thrusting my bony chest out and holding my head high, knowing that he loved me, that he, at least, did not consider me deformed.

While my mother often poked at me to straighten my spine, to braid my hair, to stop looking so cross-eyed-which was difficult since I was also told to cock my head to hide the birthmark-my father pampered me with treats and stories. He told me tales of bears turning into women fit to marry the king of heaven, of beautiful princesses trapped for three hundred years in the form of centipedes, of girls haunting the earth as nine-tailed foxes. Always, they were stories of transformation, of ugliness turning into beauty. Sometimes as he talked, I thought he looked at my birthmark with remorse, but when I would turn sharply to confront him, his eyes were filled not with guilt or shame but with bright laughter. Despite what I looked like, I was still his only child; I worked hard to be perfect in other ways.

"I am still Class Leader," I said, lifting my head. "I'm number one, Sookie's number two." I side-eyed Sookie to see if she minded my boasting, but she smiled big enough to show her teeth.

I always tried to be number one in school, the leader of the class-the one who led the line to the yard, the one who could call on rivals when I knew they would give a wrong answer. When Esteemed Teacher called on the rows to recite the countries and capitals of the world, I made sure my voice was loudest, unfaltering.

During tests when the teacher knew I knew all the answers, I was chosen to patrol the rest of the children. If they looked numb with chanting, I'd slap them on the head to wake them up. If they mumbled wrong answers, I'd mark down their names. I stood with my ear against their faces to make sure they were not just mouthing the words. I'd point at the map of the world taped on the front wall and, cunning as a fox, cull out by instinct the most vulnerable: "Lobetto, what is the capital of Germany?" "Kyung Hu, who is the prime minister of Canada? Speak up!" "Young Sik, who are the Republic of Korea's giant allies? If you do not answer by the count of three, I will make you stand in the corner to answer harder and harder questions!" By the time we graduated from primary school, Sookie was my only friend.

I grabbed a handful of yot from the table and when my father tapped my hand, I raised my eyebrows. "We need energy for homework," I said.

"Is that so?" My father laughed and picked up more of the sticky candy. He gestured to Sookie and laid three more pieces in her palm. "Then I expect you both to do extra well today." We went into the back room, rolled up our shirts and lay bare-belly on the cool stone floor to do homework.

I pushed my tablet to Sookie. "Ho Sook," I wheedled, using her formal name to show respect, "same deal?"

Sookie pinched her lips together, but nodded. She was better at art than I was, so I had convinced her to draw my homework as well as hers. I couldn't stand it when her pictures-dogs that looked like dogs, people that looked like people-received praise over my smudged circles and stick figures. In return, I would correct her English assignment. Of course, I left a few mistakes, so she would receive only an 80 or 85 percent. Only one of us should have a 100 percent. Only one of us could be class leader.

That day, we were to draw self-portraits. As I skimmed over Sookie's English paper, she stared intently at me. I tried to turn away, but she cupped my chin in her hand. The pads of her fingers flickered along the line of my jaw, my cheek, my nose, across my eyes. Then, gently-so softly I barely felt her touch-she outlined with her caresses the continent of blue-black skin that stretched from my temple to my chin. And as she touched me, she drew, as if to memorize me with each stroke of her pen.

When Sookie handed the paper back to me, I saw that she had drawn a perfect me, a me without the birthmark. Through her eyes, with her touch, I was transformed; I saw that, with the darkness erased, I had what the old ladies would call bok-saram, a face as lucky as the full moon.

After we finished our homework, I walked Sookie home. I liked to visit her apartment, especially when her mother was on base or at the club. Then we had the afternoon and the apartment to ourselves. I liked to wander through the rooms, discovering the new American knickknacks that her mother smuggled home. Once we found a small, big-eyed doll with a curled helmet of yellow hair. Another time we found a slim, green bottle called "Youth Dew"; when we pressed the button, a mist that smelled like bug spray wafted over our faces. Sometimes we'd open up a drawer and find strange things to eat, like Ho Hos. The first time I tried that chocolate roll, I spit out the cake with its too-sweet lining of sugar cream. I couldn't believe that Americans, who could have anything in the world, would eat that. I thought Sookie had played a joke on me, handing me that shiny wrapped present and telling me it was U.S.A. so I would expect something delicious.

"You're mean!" I cried, scraping my tongue with my fingernails. "That tastes like dirt!"

"No, no," Sookie laughed, tearing open another silver pouch. "It's a delicacy; you have to learn to like it. Really, really, it's American so you know it's good." She and I ate our way through the box before I decided I liked it. I saved the wrappers from those Ho Hos for a long while after that day, pasting them on my bedroom wall with chewed-up bits of rice. I liked the way the shiny paper caught and flung the afternoon light around the room. My mother, who called anything from America "whore's rubbish," threw them out while I was at school.

Sometimes Sookie and I would hit the jackpot and find not just snacks, but makeup: Touch and Glow base foundation, Beach Peach and Swinging Pink lipsticks, Coty puff powder.

"Your mother gets a lot of presents from the GIs," I said.

"I guess," she said. "You know how the Joe-sans are." I nodded, though I really didn't.

Once we walked into the apartment when her mother was at the PX and found a darkie GI sleeping in the bed. Sidling up to the bed, we bent over to study him. Sookie poked at him with the corner of her writing tablet.

"Is he dead?" I asked. I didn't bother to whisper, thinking that even if he wasn't dead, he was American and couldn't hear Korean anyway. Up close he smelled like tobacco, stale and smoky. His chest, covered with coarse kinky hair, looked dark-like the underbelly of the black pig our family once raised. I watched his belly for movement so didn't notice when he opened his eyes. Sookie screamed and when I jerked my head up, I saw his white-white eyes blinking open then shut then open. And I saw his white-white teeth mouthing "Anyang haseyo, baby-sans" like a trained monkey saying a very polite "How do you do?" before it bites. I screamed, too, I think, and pushed past Sookie to run away. Even from outside the door, we could hear him laughing.

This time I made Sookie check the apartment before I entered. "Okay, come in," she whispered. "Darkie's not here today."

"How come your mother goes with the ugly, black dogs?" I grumbled.

Sookie shrugged and turned to the desk decorated with makeup containers and beer bottles. I reached over her to touch the most elegant bottle I had ever seen: pasted over the dark brown glass was a picture of a smiling yellow-haired woman holding up a bouquet of foaming mugs.

"Try some candy," Sookie said, unwrapping a bar. "It's called Hersheys." She broke off a piece and popped it into my mouth. Sweet explosion, dark and bitter as blood, erupted in my mouth. Delicious. American. "My mother said darkies are the kindest," said Sookie, her teeth glistening with strings of chocolate. "The most grateful. They go with anybody who is lighter than them. Even the ugly ones." She gulped the last of the Hersheys. "I could get a darkie," she said, licking her teeth. "Even you could, maybe."

We looked at our faces in the mirror, cataloging our ugliness. My birthmark gleamed, an ebony light, black as Africa. Sookie held up a white jar. "Pond-su cream," she said to my face in the mirror. "Made in the U.S.A."

"Pansu?" I repeated. "Reflection cream?"

"Uh-huh." Sookie twisted open the jar and scooped the cream onto her fingers. She sniffed at it. "First time I found this, I thought it smelled so good, I ate it." She giggled, then poked the tip of her tongue into the mass. "Even knowing how horrible it tastes, I still can't resist."

Sookie rubbed the Pond-su over my birthmark. "To lighten and soften your skin."

I held my breath and as she rubbed, I thought I could see my stained skin dissolving under the layer of white cream.

"Look," Sookie breathed. "You are almost beautiful."

Our eyes met in the glass. We looked from my face to Sookie's. Sookie lifted her arms. "I don't think there is enough Pond-su cream in this jar to cover my whole body," she said, trying to joke away her ugliness.

"Mmmm," I said, "then you just have to go to America where you can buy all you want."

Sookie's reflection lowered its arms, stopped smiling. "Yes," the mouth said. "That's what I am going to do."

It turned out that Sookie did not need Pond's Cold Cream to cover up her ugliness. Her ugliness turned into beauty without her having to do a thing. She didn't grow into beauty with womanhood-her boyishness developing into lush curves. Her body stayed long and thin, what the old grandmothers still call unlucky. Her skin didn't lighten with age; her face did not grow into her overly large eyes. In fact, she looked much the same as an adult as she had in childhood. There were times when we were grown that I saw her as I did when I was younger, and was shocked into remembering that she was as ugly as she always was. And I would be reminded that what had changed was not so much how we looked, but how we looked out of our own eyes, our perceptions of beauty and of ourselves.

When the Americans first ventured off the base and into our neighborhoods, we though that they-with their high noses, round eyes, and skin either too white or too dark-were ugly. "Kojingi," we would squeal, shielding our faces from the Big Noses. Or, holding our own noses as we ran away from soldiers who smelled like decaying boots, we sang out, "Shi-che nemsei!"

Slowly, though, we began to view their features as desirable, developing a taste for large noses, double lids, and cow eyes just as we had learned to crave the chocolate candy and cakes we had once thought sweet as dirt.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved